Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

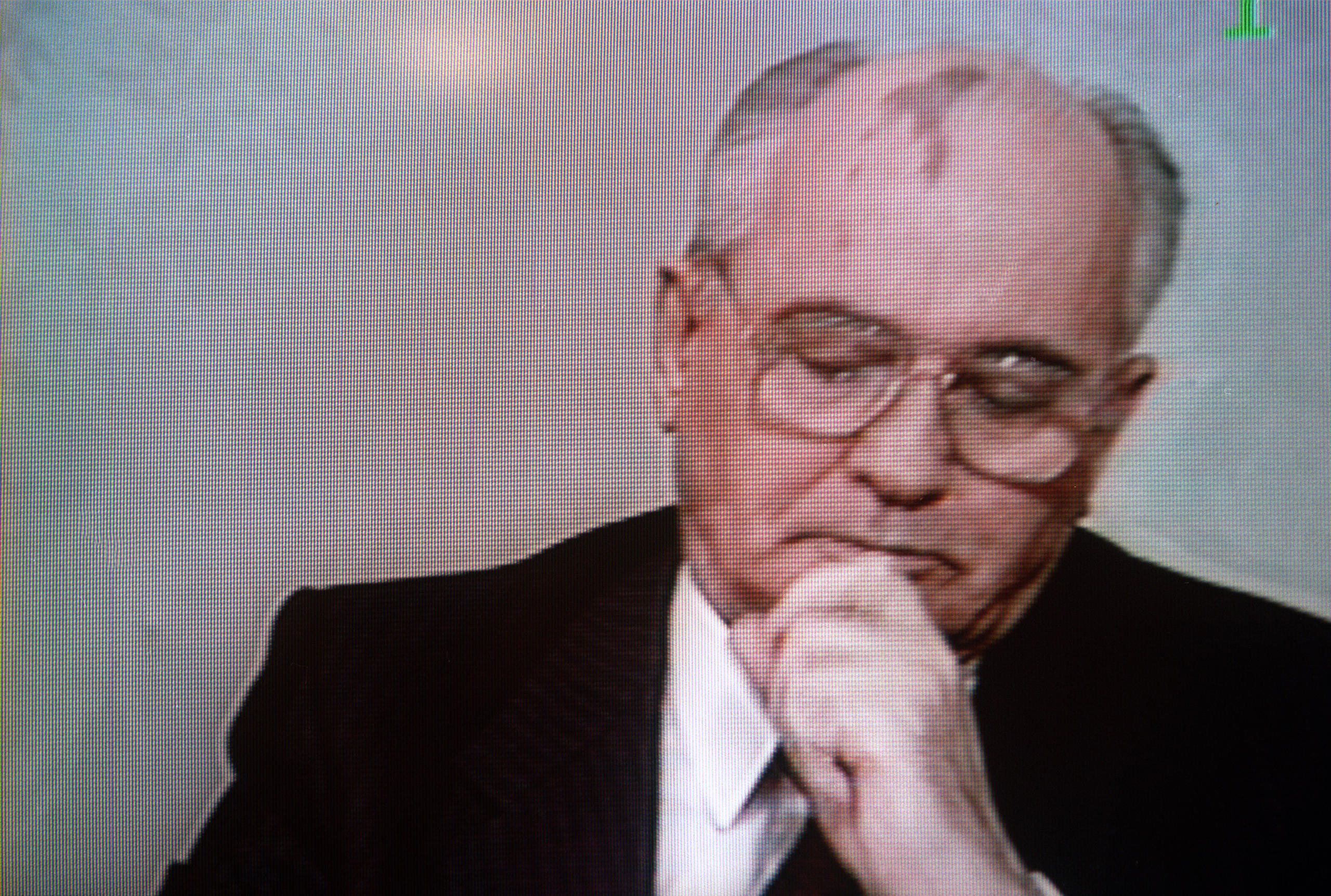

Thirty years ago this week, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Mikhail Gorbachev, its final leader, resigned in a televised address from his presidential office. Actually, he spoke not from his office but a TV facility in the Kremlin that had been mocked up to look like it. According to Conor O’Clery, a former Moscow correspondent for the Irish Times, nearly thirty staffers from CNN were on hand to film the address. An Associated Press photographer and ABC’s Ted Koppel were also hanging around. Tom Johnson, CNN’s president, furnished the pen with which Gorbachev signed away his power after his own felt tip ran dry; he then surrendered the nuclear briefcase in a corridor as CNN’s crew filed past with its equipment. In the end, “only the Western media was still interested” in what Gorbachev had to say, O’Clery writes. “The Soviet Union expired in a fake presidential office, crowded with Americans, and with the stroke of a German pen provided by a Western media executive.”

The dissolution of the USSR had been expected, if not inevitable, for some time, and was all but sealed earlier in December 1991, when the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus—then still Soviet republics—met at a snowy hunting retreat and declared the union a dead letter in front of a small group of journalists. Press freedom, long curtailed in the Soviet Union, had started to flourish after the mid-eighties, when Gorbachev initiated the process of glasnost, meaning greater openness in public affairs; he envisioned this as being limited, but lost control of his reform project as journalists started to publish information about the Soviet system. As Ann Cooper, who was NPR’s Moscow correspondent at the time, has written, two publications in particular, Ogonyok and Moscow News, pushed the envelope; the latter would sell out so quickly at newsstands that many people had to read display copies in glass cases outside the paper’s offices. In August 1991, when Communist hardliners tried and failed to take power in a coup, journalists were among those who led the fightback, shooting footage of protests and confronting coup leaders with sharp questions. By that time, “the press was incredibly free, and doing good journalism,” Cooper told me yesterday. “It was such a striking contrast with when everything was controlled by the party and the press was just horrible—it was very propagandistic, it was boring, it was gray.”

New from CJR: Our anniversary issue

Recently, Cooper used an image of people reading Moscow News on the street to open a panel discussion that she convened, at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center, to assess where the press stands now in the fifteen countries that emerged from the USSR’s ashes—a critical question for the state of democracy in a region of three hundred million people that stretches from the European Union to the borders of China and North Korea. Thirty years ago, she said, there was hope that many of the fifteen countries would institutionalize media freedom, but the “reality is not exactly what we imagined back then.” The Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia have been success stories—Reporters Without Borders now ranks them all among the thirty best countries in the world for press freedom—but other post-Soviet nations still have harshly repressive media environments, not least Turkmenistan, which RSF ranks as the third worst country in the world for press freedom, and Belarus, where the dictatorial president, Alexander Lukashenko, has led a brutal recent clampdown on independent journalism, as Charles McPhedran has reported for CJR. Other countries, Cooper says, fall in between, boasting dedicated, if small, cadres of independent reporters working through fluctuating political conditions. They include Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.

The latter country has been in the news in the US a lot lately, due to the specter of Russian invasion along its eastern border, and in November, Ukraine’s media also made headlines among Western media reporters after Adnan Kivan, a construction mogul, abruptly fired the entire staff of the Kyiv Post, a punchy English-language news outlet that he owns. Brian Bonner, the Post’s editor, told CJR’s Maria Bustillos at the time that he thinks Kivan “got tired” of powerful people complaining to him about the Post’s aggressive coverage (Kivan denies this); staffers from the paper have since launched a new site, the Kyiv Independent, and pledged to rely on reader donations for funding rather than “a rich owner or an oligarch.” Oligarchs control much of Ukraine’s press landscape—part of a broader phenomenon of concentrated media ownership across post-Communist Europe that dates back to the rapid privatization of the early nineties and persists to this day, especially in the TV industry. If the Post symbolized Ukraine’s culture of vibrant independent journalism, Kivan’s decision demonstrates its ongoing fragility.

Moldova, a small country nestled between Ukraine and Romania, tends to get less Western media attention, but that’s started to change in the last year following the election of Maia Sandu, a pro-Europe liberal, as president, beating a candidate openly backed by the Kremlin. There, too, a committed community of investigative journalists has worked to expose corruption and abuse, as much of the rest of the media has remained under oligarchic and political influence. Sandu has promised to root out corruption and has won praise from Western leaders, including President Joe Biden, who namechecked Moldova as a beacon of hope for global democracy in a recent speech at the United Nations. Corina Cepoi, a Moldovan journalist who appeared on Cooper’s recent panel, said that the government has already started to push for reforms that would create more transparency around media ownership in the country and perhaps begin to diversify it. Cooper told me, however, that other Moldovan reporters with whom she’s spoken remain somewhat skeptical that Sandu represents a clean break with the past.

Among the post-Soviet countries, Russia still looms largest. State-backed disinformation campaigns have snaked out beyond the country’s borders—Sandu, for instance, has alleged that she was the target of pro-Russian “fake news” as she ran for election in Moldova last year—as the climate for independent journalism within Russia itself has grown increasingly hostile, with officials tarring many news organizations and journalists as “foreign agents” and effectively outlawing others while also expelling foreign correspondents, including, recently, the Dutch newspaper reporter Tom Vennink. Dmitry Muratov, a high-profile Russian journalist, came of journalistic age in the Glasnost era; after the USSR fell and press freedom flowered, he cofounded Novaya Gazeta with some financial support from Gorbachev, who donated some of his Nobel Peace Prize winnings to the publication. Two weeks ago, Muratov himself was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize, as a prominent example of the official threats journalists now face the world over. “Journalism in Russia is going through a dark valley” with some reporters fleeing the country, Muratov said in his Nobel lecture. “That has happened in our history before.”

The conditions for independent journalism may differ between post-Soviet states, but its importance is not in question. In many places, it is barely able to survive; where it has taken root, Cooper told me, it is often still dependent on financial support from Western governments and NGOs that started funding post-Soviet media thirty years ago, and might have hoped that it would be able to support itself by now. It’s tempting, Cooper said, to look at the media landscape in the former USSR and ask, “well, gosh, what really was accomplished? Was thirty years enough?” The answer, she says, is that “thirty years actually wasn’t enough.”

Below, more on press freedom around the world:

- The United Arab Emirates: Dana Priest reports, for the Washington Post, that in the months before the Saudi state assassinated the dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, officials in the United Arab Emirates detained his fiancée Hanan Elatr and infected her phone with Pegasus, a spyware tool developed by an Israel firm. An analysis of Elatr’s phone that was conducted by Citizen Lab, at the University of Toronto, “provides the first indication that a UAE government agency placed the military-grade spyware on a phone used by someone in Khashoggi’s inner circle in the months before his murder,” Priest writes. The UAE continues to deny using Pegasus.

- Egypt: On Monday, a court in Egypt sentenced two journalists, Alaa Abdelfattah and Mohamed Oxygen, to five and four years in prison, respectively. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, “Egyptian authorities have held Abdelfattah, a freelance journalist and blogger, and Oxygen, a blogger whose real name is Mohamed Ibrahim, since September 2019, while investigating them under terrorism and false news charges.” Monday’s verdict cannot be appealed and the terrorism charges remain pending.

- China: Muyi Xiao, Paul Mozur and Gray Beltran, of the New York Times, obtained documents showing how the government of China has employed private contractors to flood global social media with a campaign to “burnish its image and undercut accusations of human rights abuses.” Much of the effort “takes place in the shadows,” Xiao, Mozur, and Beltran report, “behind the guise of bot networks that generate automatic posts and hard-to-trace online personas.” Chinese officials have used the campaign to track down critics outside China and trace their connections to the mainland, in some cases threatening their family members.

- The UK: Tim Tate, a documentary filmmaker in the UK, has accused the British government of deceitfully withholding documents that would shine a light on its reaction, in the nineteen-eighties, to the book Spycatcher, in which Peter Wright, a former intelligence operative, accused British agencies of various abuses; public files are typically released after thirty years in Britain, but officials have cited legal exemptions to block the publication of documents that Tate is trying to review. The British government tried to block Spycatcher from being published in Australia, and also tried to gag newspapers in the UK from reporting details of Wright’s claims. The Guardian has more.

Other notable stories:

- Sara Fischer and Neal Rothschild report, for Axios, that the surge of the Omicron variant is not yet “jumpstarting Americans’ engagement in COVID news,” at least as far as social-media interaction with individual articles is concerned. Elsewhere, major news outlets are continuing to reinforce their COVID protocols, with the Times and ABC News telling staffers to work from home where possible. And at least two members of the White House press corps tested positive this week. Politico reports that White House correspondents are “asking questions like: Is it worth getting infected with COVID-19 to lob Jen Psaki a question that she will likely respond to with prepared talking points?”

- On Monday, Jesse Watters, a host on Fox, encouraged young conservatives to publicly “ambush” Dr. Anthony Fauci with questions about US funding for coronavirus research in a Chinese lab, and to film the encounter. “Now you go in for the kill shot,” Watters said, referring to the lab question. “Deadly. Because he doesn’t see it coming.” Responding to Watters’s rhetoric on CNN yesterday, Fauci said that he “should be fired on the spot,” but predicted that he wouldn’t be. Later, Fox said that Watters’s “words have been twisted completely out of context,” and that his violent language was clearly metaphorical.

- The Post’s Paul Farhi asks whether it’s okay for Thomas Friedman, a columnist at the Times, to write about charities that he supports without disclosing his donations: news organizations typically prohibit journalists “from taking anything of value from those they write about,” Farhi writes, “but giving money, particularly without notifying readers, is rarely addressed.” The Times says that it has “no ethical concern” with Friedman’s donations, but journalism-ethics experts argue that he should be more transparent.

- Fischer, of Axios, reports that Jimmy Finkelstein, who sold The Hill to Nexstar earlier this year, is looking to get back into media ownership: he’s planning to launch a new media company with hundreds of staffers and a national footprint, while also considering investing in existing outlets, including the Miami Herald. In 2019, Finkelstein came under scrutiny after The Hill became embroiled in then-President Trump’s first impeachment.

- For CJR, Richard J. Tofel recounts how, in 1969, the western world and its media were “swept by a story that Paul McCartney had died in an automobile accident three years earlier, been secretly replaced by a double chosen in a lookalike contest, and that clues to this were strewn throughout recent Beatles albums.” The story, Tofel argues, can help us to think about disinformation outside of the context of America’s current polarization.

- For Poynter, David Cohn explores how glossy magazines started sending curated “product boxes” to their readers as a new form of e-commerce, and predicts that local outlets will soon get in on the action, including by creating local cookbooks and giving guides. “A local publication that understands its community is in the perfect position to leverage its business relationships to put itself at the center of commerce,” Cohn writes.

- The New Yorker’s Calvin Trillin reflects on the art of the newspaper lede. “I admire those short, punchy ledes often employed by crime reporters,” he writes, but also “the ambition of those long ledes which you sometimes see in the obituaries that appear in the New York Times—ledes whose first sentence manages to stuff the highlights of an entire lifetime in a clause between the decedent’s name and the fact that he has expired.”

- Lit Hub compiled the most scathing book reviews of 2021. They include Dale Peck on Andrew Sullivan’s essays (“all the appeal of plunging an overfull toilet”), Noah Kulwin on Malcolm Gladwell’s foray into military history (“written to look like something an HSBC junior analyst might tell himself after a bad quarterly review”), and Elie Mystal on John McWhorter’s Woke Racism (“a Tucker Carlson segment without the bow tie and smirk”).

- And this newsletter is taking an extended break for the holidays. I’ll be back in your inboxes on Monday, January 10. Thanks for reading this year. Stay safe and eat well.

ICYMI: Biden, Manchin, and the stakes behind the slogans

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.