Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

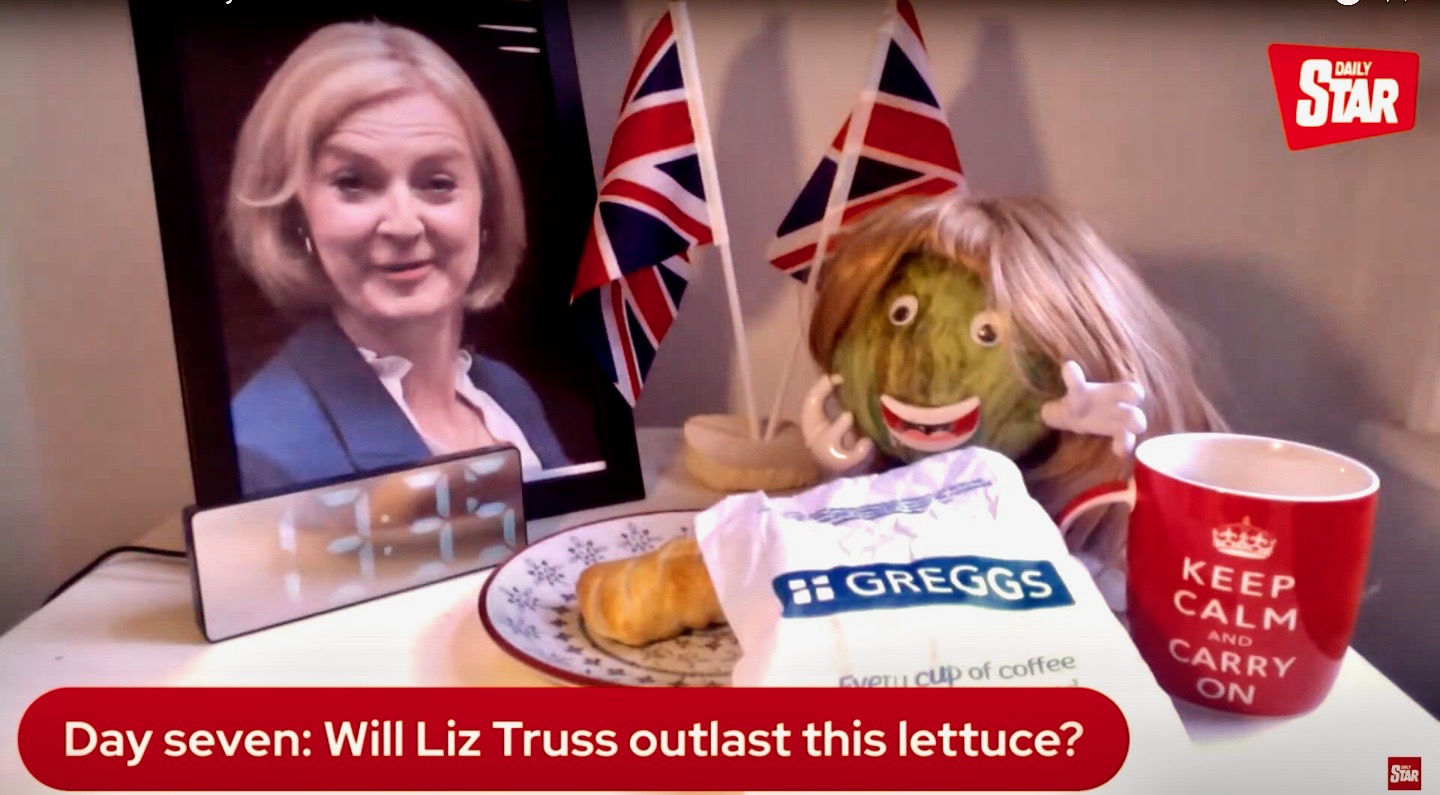

Ten days ago, with Liz Truss, Britain’s new prime minister, in the process of tanking the country’s economy, The Economist laid into her with a scathing editorial headlined “The Iceberg Lady.” Putting aside the ten days of official mourning that followed the death of the queen, Truss was “in control” for just seven days before her attempted budget blew up in her face—“roughly the shelf-life,” The Economist noted, “of a lettuce.” A week ago, a less austere publication, a tabloid called the Daily Star, decided to make the metaphor literal, setting up a video livestream of a real-life lettuce next to a photo of Truss, and asking which would last longer. Initially, the scene was spare save for a pair of googly eyes on the lettuce, but as days passed, it picked up some accoutrements: a blond wig, a glass of wine, and—after Suella Braverman, Truss’s interior minister, attacked readers of The Guardian as the “tofu-eating wokerati”—a plate of tofu.

When the Daily Star set up its livestream, Would the lettuce last longer? was already a live question, even though Truss had only been in office for six weeks. By the time the tofu appeared, her government was in full-blown crisis. On Wednesday, she attempted a public-facing reset, plotting a combative performance at a parliamentary question session and a media visit to a tech-manufacturing firm. She did the combative parliamentary bit—“I am a fighter and not a quitter,” she roared—but then canceled the media visit, initially without any explanation. It transpired that Braverman was in the middle of resigning or being fired, depending on which reporter’s account you believed. From there, things only got worse: officials declared that a vote on fracking would double as a vote of confidence in the government but then appeared to walk that back, leading to chaotic and angry scenes among government lawmakers; reporters covered the meltdown in real time, relying on tips from inside Parliament—including the claim that Craig Whittaker, a senior government whip, had stormed out shouting “I am fucking furious and I don’t give a fuck anymore”—as well as photos captured by an opposition lawmaker. Tom Bradby, the anchor of ITV’s nightly news show, later quoted Whittaker’s words in an extraordinary intro that quickly went viral. (He at least switched out the curse words for “effing”; in her coverage, Annette Dittert, a German TV correspondent, did not.) At 1:30am, political reporters received a text from a government spokesperson confirming that the fracking vote was a confidence vote after all, and that lawmakers who bucked it would pay a price.

ICYMI: Why we should think twice before using the term ‘migrant’

When morning finally dawned yesterday, the media was rife with speculation that Wednesday’s chaos would be the death knell for Truss, though it was nonetheless a shock when this proved to be the case a few hours later. The resignation of Truss’s predecessor, Boris Johnson, played out over a period of months, with reporters often parsing clues to suggest that his end might be nigh—the appearance of a senior lawmaker who is effectively the government’s designated Grim Reaper; the hasty convening of a government press conference—only for Johnson to survive another few weeks. This time, the same clues tumbled in quick succession, and Truss was out; addressing the media from a lectern in Downing Street, she made a half-hearted stab at defending her legacy before confirming her intention to stand down next week, once a successor has been named. The media, predictably, had a field day. The BBC opened one of its news shows by rolling a montage of Truss footage to the Rihanna song “Take a Bow.” (“You look so dumb right now / Standing outside my house.”) Channel 4 closed out one of its news shows with its own Truss montage to Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space,” which Truss has said is her favorite song. (“So it’s gonna be forever / Or it’s gonna go down in flames.”)

No one, of course, took as much of a victory lap as the Daily Star. When Truss resigned, her photo was flattened on the lettuce-cam livestream and “God Save the King” rang out, followed by disco lights and “Celebration” by Kool & the Gang. (When I checked back this morning, the feed was still live, with the lettuce asleep on camera behind an eye mask.) In print, the Star published a “HISTORIC SOUVENIR EDITION” bearing the banner front-page headline “LETTUCE REJOICE” and a picture of the lettuce with a crown and a glass of bubbly. A picture of the lettuce was also beamed onto an outside wall of the Houses of Parliament. By this point, the lettuce had won huge international infamy, including in US media. “The Lettuce Outlasts Liz Truss,” the New York Times declared in a headline that I did not have on my 2022 bingo card.

I wrote about Truss shortly after she took office last month, assessing what her pattern of both bashing and dodging the media during her leadership campaign might portend for her government’s media relations, and where she stood on key media policy questions, not least the fate of the BBC’s funding model. The policy stuff turned out not to matter since she never got around to it. She did do some media appearances as prime minister, and they probably contributed to her downfall, not least a disastrous round of local radio interviews in defense of her economic policies (if she expected an easier ride than from national journalists, she did not get one) and a brief press conference last week during which she flailed in response to questions about her future, including from outlets that have been favorable toward her in the past, then walked out. Last week, a former Truss aide claimed publicly that she had, in the past, invented family bereavements—“Only minor people, like aunts and cousins and things”—to get out of media commitments because she hated doing them so much. (She eventually “ran out of excuses.”) Contempt for journalists isn’t the only reason that politicians try to dodge them.

On the subject of outlets that have been favorable toward Truss in the past, The Guardian’s Jim Waterson noted yesterday that various right-wing newspapers backed her bid for power over the summer but “backpedaled” after she unleashed economic carnage. Nowhere has this been more true than at the Mail, a right-wing tabloid that ran pro-Truss stories throughout her leadership campaign—as well as stories critical of her main leadership rival, Rishi Sunak—and after she took office, with headlines like “Cometh the hour, cometh the woman,” and, after she started to outline her economic plans, “AT LAST! A TRUE TORY BUDGET.” By last weekend, the Mail’s front page was asking “HOW MUCH MORE CAN SHE (AND THE REST OF US) TAKE?”; this morning, it splashed a column by Sarah Vine, a right-wing commentator, describing Truss as “a disastrous dalliance who served only to remind us what a real leader looks like.”

Other right-wing papers, including at least one that backed Truss for the leadership, didn’t even lead with Truss this morning, despite her extraordinary resignation. Almost unbelievably—and yet entirely believably—the main character was instead Boris Johnson, who reportedly fancies a comeback (which of course he does), briefing the press yesterday that he considers his return to be “a matter of national interest” (which of course he doesn’t, or at least you’d hope not). Johnson, not Truss, was pictured on the front pages of The Sun (“BOJO: I’LL BE BACK!”) and the Express (“HE COULDN’T COULD HE”). The Mail pictured him underneath its Truss lead, with Vine’s column blasting Truss also referring to the prospect of a Johnson comeback as an opportunity for the governing Conservative Party to “restore some semblance of respect” in the country. Johnson, lest we forget, fell from office under a crushing weight of scandal earlier this year, but the British press—on the right, but also in more mainstream quarters—never buried him as a political character, speculating as Truss was being chosen that he’d find a way to stay in office, then that he might one day come back. That day could now come remarkably fast.

After Johnson announced his resignation, I wrote that he had fallen prey, in part, to both his own incorrigible lack of integrity—honed during his past life as a journalist—and the fickle cut and thrust of a news cycle that sees politics as a blood sport (and that Johnson, as a journalist, once stoked). I also warned that “Johnson has nourished a media narrative that he is the master of the comeback,” and that the British press would have to be careful “not to help him launder that further or whitewash his tarnished record just because he’s a colorful character who makes for better copy than his wooden successor.” In truth, I did not think such a swift Truss collapse, or Johnson resurrection, likely; I was wrong, and, through one lens, the persistent media attention to his lingering comeback ambitions could be viewed as prescient coverage of a story that hadn’t yet ended. I come back, though, to Johnson’s skill at gaming the media—his ability, again surely honed as a journalist, to not only ride narrative waves but to create them. Viewed this way, to present Johnson—who was desperately unpopular when he left office—as a natural comeback kid, or “winner,” is to be complicit in the myth of his own inevitability. If Johnson is to return, he need not convince the wider electorate, just the comparatively tiny membership of his party and, first, his Conservative parliamentary colleagues. The Times of London reported this morning that those are starting to offer him support—not, in the words of a “source close to Johnson,” because they “want him but because they believe he’s going to win.”

I also wrote after Johnson’s resignation that parallels that media figures have often drawn between him and Donald Trump have often been facile. If Johnson’s bid to return gathers any more momentum—and, before we get ahead of ourselves, that’s no guarantee yet; he must meet a high hurdle of nominations among his colleagues, who kicked him out not six months ago—those comparisons are likely to flow through sections of the press again. And yet the two remain very different characters, in general and in their hunt for a comeback, and they sit within different media ecosystems, particularly on the right. To overgeneralize somewhat, right-wing media types in the US often exhibit nauseating fealty to Trump; there are Johnson true believers in the UK’s right-wing media scene, to be sure (and those whose interests may be more directly entangled with his), but again, it strikes me as a more fickle realm than its American counterpart, at least at the moment—right-wing papers, in particular, can still turn on a dime when it seems expedient for them to do so, a calculation swayed by numerous factors, perceptions of momentum and success surely among them. Whether the end result is much different is a separate question.

The Daily Star lettuce somehow reflected this very tabloid sensibility: the paper clearly saw blood in the water and capitalized on it to devastating effect. But the Star is in a separate category from its right-wing tabloid rivals: it styles itself as nonpartisan, and has increasingly lampooned the bizarro world of British politics more than trying to shape it; likewise, the lettuce, intentionally or not, satirized the dog-eat-dog culture of tabloid coverage as much as it channeled it. “Plucky Daily Star veg outlasts Lettuce Liz as she wilts in political heat,” the front page read this morning. “And you won’t believe which cabbage might be coming to save us.”

Below, more on British media and politics:

- The view from abroad: The world’s media once again found itself dissecting a change of leadership in Britain, just weeks after welcoming Truss into office (often with lashings of skepticism). The Sydney Morning Herald wrote that Truss’s short-lived administration highlights “a worrying trend evident in many Western democracies—the rise of politicians ill-prepared and ill-suited to high office,” while the Irish Times was more scathing still, writing that “the mother of parliaments has been reduced to a bad joke, its constitution a laughing stock.” In France, Le Figaro described Truss’s “descent into hell”; in Italy, the Corriere della Sera likened the instability in Britain to “the Roman theater that we know well”; in Germany, Bild hailed a “Brit-quake.” The BBC has a roundup of the coverage.

- Blue language, I: On Wednesday, with chaos unfolding in Parliament, Krishnan Guru-Murthy, a prominent anchor on Channel 4, was caught on a hot mic calling Steve Baker, a prominent right-wing Conservative lawmaker, a very bad word that I won’t repeat here; Baker had just criticized Guru-Murthy’s journalism on air. Guru-Murthy apologized to the public and to Baker; Channel 4 responded by taking him off air for a week. (A week earlier, Guru-Murthy had been in the interviewer’s chair when a Financial Times journalist characterized a government claim on the economy as “bollocks” during a live interview. He later consulted Britain’s broadcasting rules to see if the use of the word was an infraction, concluding that it can be but isn’t always. He then apologized—for the fact that “bollocks” was spelled incorrectly on the network’s subtitles.)

- Blue language, II: After Truss won the prime ministership, James Heale, a journalist at The Spectator, and Harry Cole, The Sun’s political editor, revealed that they were working on a book about her first days in office, entitled Out of the Blue, and that it would be released on December 8. According to Bloomberg, Heale and Cole still plan to release the book, but with edits and a new chapter covering her last days in office, too. (“The tenses will have to change,” Heale said.) On Wednesday, Keir Starmer, the leader of the opposition Labour Party, had referenced the book in order to mock Truss, noting that “out by Christmas” could refer to either its publication date or its title.

- Unreality TV: Yesterday, a parliamentary committee rebuked Nadine Dorries, a right-wing lawmaker and Johnson ally who served as culture minister in his government, for claiming that Channel 4 used actors to fake a TV show that she once appeared in about the reality of living in poverty. Dorries has stood behind her allegation, but the makers of the show have strongly denied it and the committee has now concluded that Dorries’s claim is not “credible.” The Guardian’s Waterson and Mark Sweney have more. Relatedly, Dorries is set to guest-host an episode of Piers Morgan’s show on TalkTV next week. For all we know, she could be back as culture minister by then.

Other notable stories:

- In the past, Russia and Iran have launched disinformation campaigns aimed at disrupting US elections, but neither country has yet been found to have targeted the midterms, with cybersecurity and law enforcement sources telling Zeba Siddiqui and Christopher Bing, of Reuters, that the biggest threats this time are homegrown. Far-right networks, for example, have targeted local poll workers with false claims of corruption.

- Benjamin Mullin and Katie Robertson, of the Times, ask whether we’re past “peak newsletter,” finding that the “bubble may be popping” for the idea that the format would revolutionize the media industry while allowing that some outlets are still finding success with it. Newsletter optimism is “not as hot and as frothy as it was,” Nicholas Thompson, The Atlantic’s CEO, said, “but I also don’t think this is the end of newsletters.”

- The family of George Floyd is suing Ye, the artist formerly known as Kanye West, on grounds including defamation and harassment after Ye falsely claimed, on the podcast Drink Champs, that Floyd was not murdered by a police officer but died from fentanyl use. Victor Santiago—a host of Drink Champs, who is also known as N.O.R.E.—has acknowledged that he “made a mistake” in not pushing back harder on Ye’s remarks.

- Nature is out with a special issue focused on racism in science—a “toxic legacy” that the publication acknowledges it helped create. The issue is also the first in Nature’s history to have been guest-edited. Science is “a shared experience, subject both to the best of what creativity and imagination have to offer and to humankind’s worst excesses,” Melissa Nobles, Chad Womack, Ambroise Wonkam, and Elizabeth Wathuti write.

- For CJR, Helen Benedict argues that journalists should think twice before using the term “migrant.” News organizations use the word all the time, and yet many of the people in their stories “are not migrants but asylum seekers or refugees—people escaping war, persecution, or local and lethal violence; people who cannot go home,” Benedict writes. “If that is who we are writing about, ‘refugee’ is the word we should use. Not ‘migrant.’”

- The Committee to Protect Journalists called on authorities in Colombia to investigate the killing of Rafael Emiro Moreno, a journalist who was shot in Montelíbano, a northern town, on Sunday evening. Moreno reported on political corruption and drug-trafficking groups, and was the director of Voces de Córdoba, a news site. A bodyguard assigned to Moreno by a government protection unit was off-duty at the time he was killed.

- Dake Kang, of the AP, profiled Wang Zhi’an, an investigative journalist and former star of Chinese state TV who has been forced to move to Tokyo after being blacklisted in his home country. Wang says that President Xi Jinping has muzzled China’s once flourishing media scene. “He demands absolute obedience,” Wang said, of Xi. “The media has become like the army: a tool that pledges unconditional allegiance to the party.”

- The Australian Broadcasting Corporation warned the country’s parliament that a national anti-corruption commission could demand documents leaked to the broadcaster by confidential sources, circumventing other safeguards for journalism in the commission’s mandate and potentially exerting a “chilling effect,” The Guardian’s Paul Karp reports. In 2019, police raided the ABC as part of a leak probe, as I reported for CJR at the time.

- And Defector’s Laura Wagner argues that Semafor, a buzzy news site that launched this week and has pledged to fight polarization by reinventing the news article, is actually part of the problem. Rather than restructure how media is funded and run, she writes, Semafor is offering an “unserious half-measure that would only sound good to the class of people who write checks for this kind of thing.” (I also critiqued Semafor this week.)

ICYMI: The Wire pledges transparency as it reviews its Meta coverage

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.