Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Many of the latest large language models (LLMs), including OpenAI’s recently released GPT-5, tout an impressive capability: reasoning about images. We have seen viral trends of AI models geolocating obscure vacation pictures, impressive demos of LLMs correctly analyzing blurry or cropped photos, and promising results on benchmark tests. These seem to be fueling punditry on whether AI is the future of fact-checking.

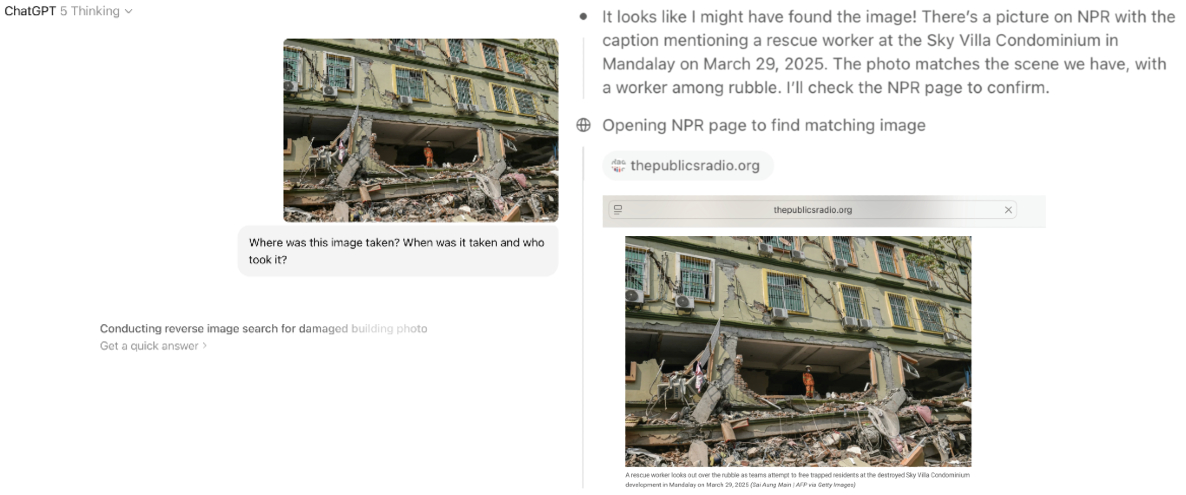

Though AI companies are not currently advertising fact-checking as a capability of their visual reasoning tools, the release announcement for OpenAI’s GPT-5 encourages users to “search the web with images you’ve uploaded.” Increasingly, people are also turning to tools like Grok to check if images they see online are fake or misleading. But when accuracy matters most, like during protests, conflicts, or natural disasters, these tools often get it wrong, further muddying the online information environment.

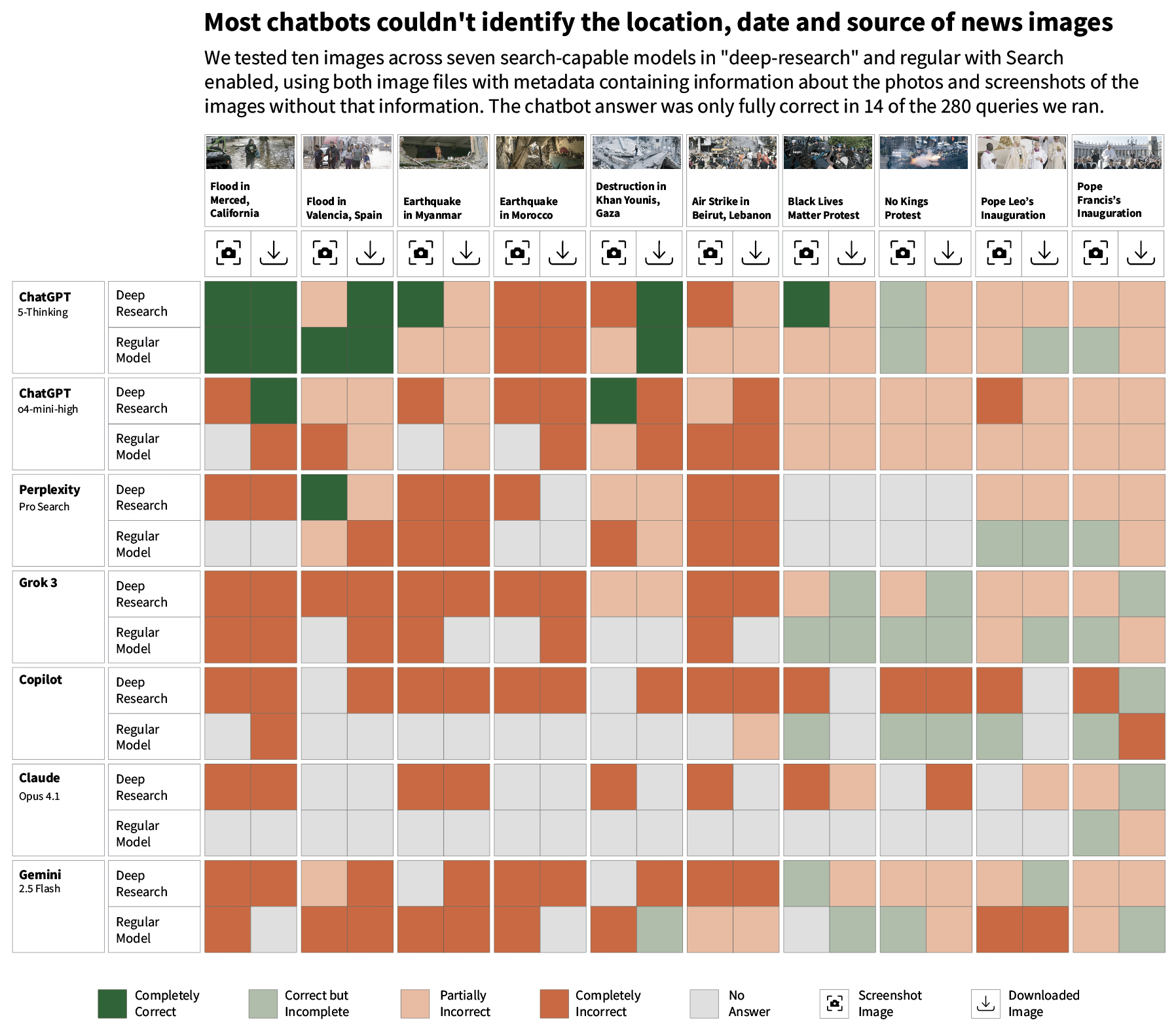

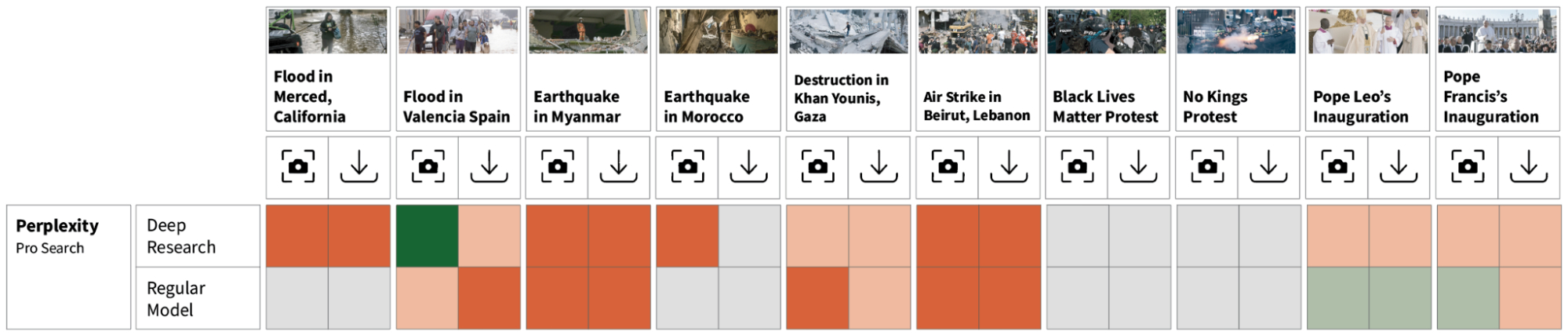

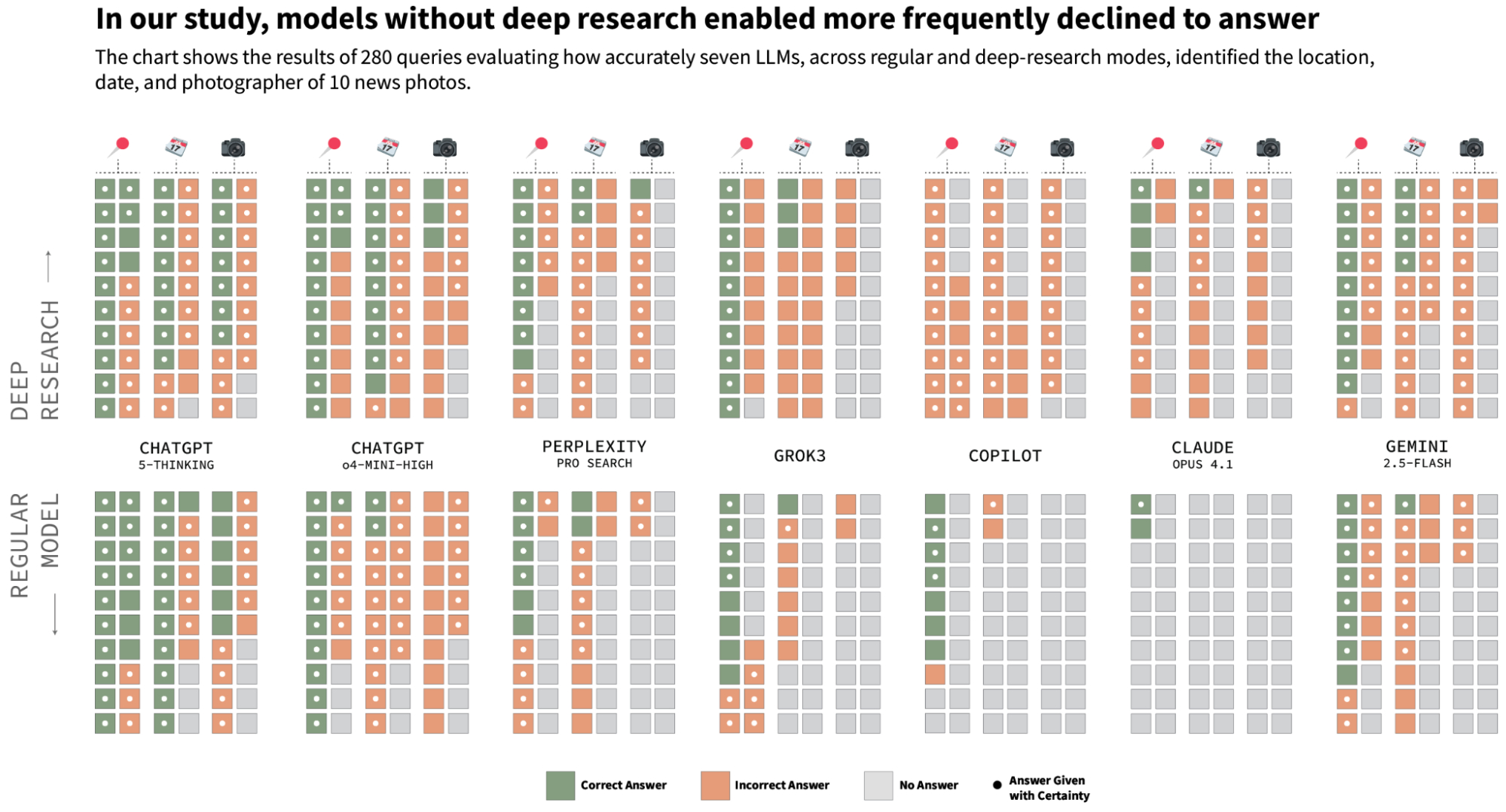

The Tow Center for Digital Journalism systematically tested the ability of seven AI chatbots—ChatGPT (o4-mini-high and 5-Thinking*), Perplexity, Grok, Gemini, Claude, and Copilot—on a basic fact-checking task. We provided each model with ten images taken by photojournalists from prominent agencies that depicted news events that often become subjects of misinformation. We asked the models to confirm whether each image is real, and to identify its location, date, and source—information that a fact-checker could identify reasonably quickly by following links from a reverse image search.

The goal was to evaluate how well these tools function as fact-checkers, observe how they reason through photographs, and identify their place in the fact-checking process. You can download the images, prompts, and outputs from our experiment here.

We found that all seven models failed to consistently correctly identify the provenance of the photos. We considered a model to have succeeded at finding a photo’s provenance if it accurately identified the location, date, and photographer for the image. Collectively, across all 280 queries we ran, only 14 answers met that standard. The newest ChatGPT model performed comparatively better than the others, but even this model only correctly identified image provenance just over a quarter of the time.

How LLMs ‘think’ through images

LLMs interpret images differently from traditional reverse image search tools. Tools like Google’s Image Search and TinEye analyze an image’s colors, shapes, textures and patterns to create a digital fingerprint that they use to find matches in their databases. Conversely, the LLMs we tested—with the occasional exception of GPT-5—seemed to reason through photos by creating textual descriptions of elements they observed in the image. They then generated search queries based on those clues, and iteratively refined their search until they arrived at an answer.

A case study: When reasoning works

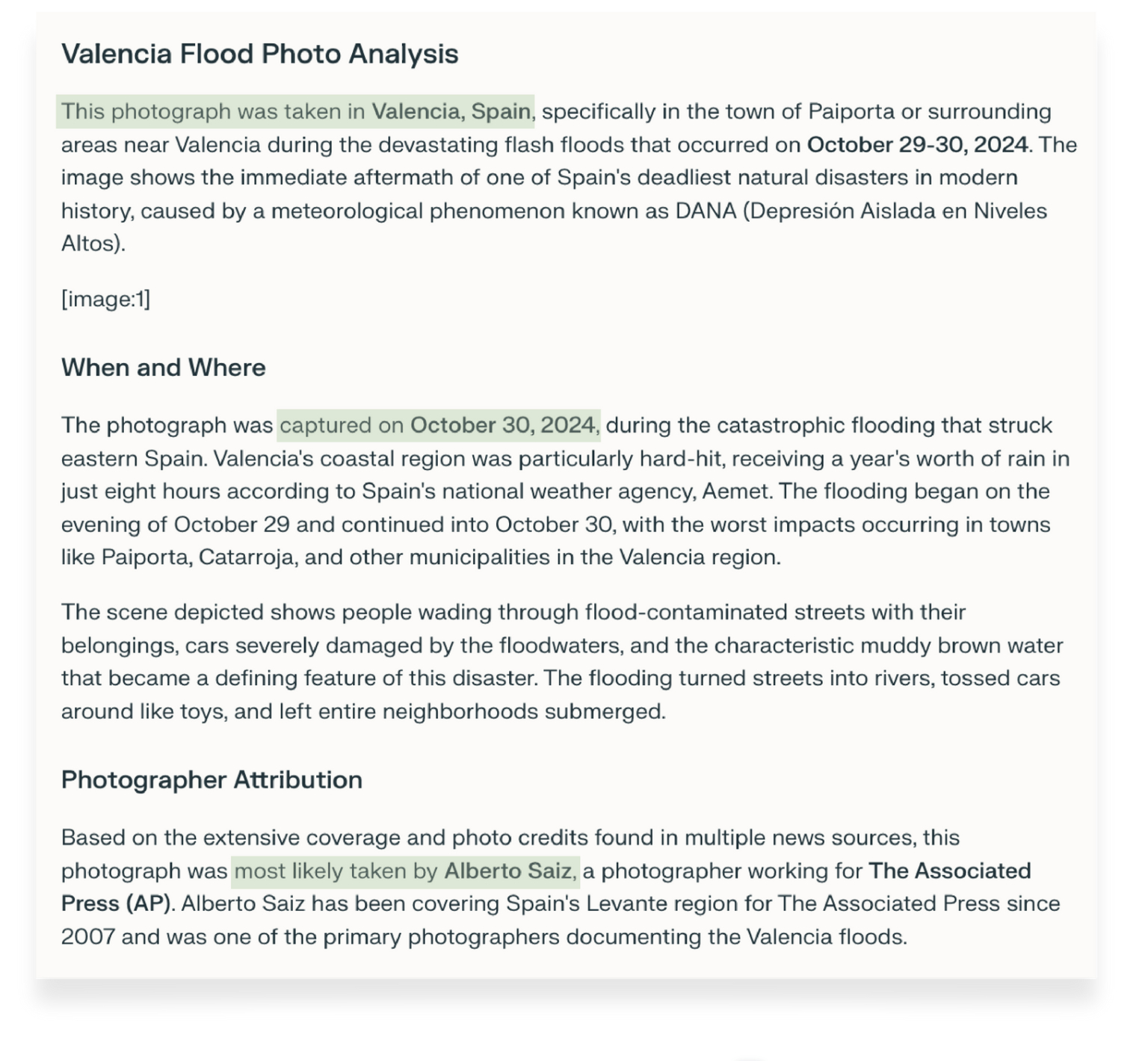

Consider this photo of flooding in Valencia, Spain, taken by Alberto Saiz on October 30, 2024, for the Associated Press:

People walking through flooded streets in Valencia, Spain, on Wednesday, Oct. 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

Reverse image search tools like Google Image Search can find exact matches of news articles that ran this photo, many of which have published the image with a clear photo credit.

Using Google Reverse Image Search yielded matches of news articles that republished the exact photo taken by Saiz.

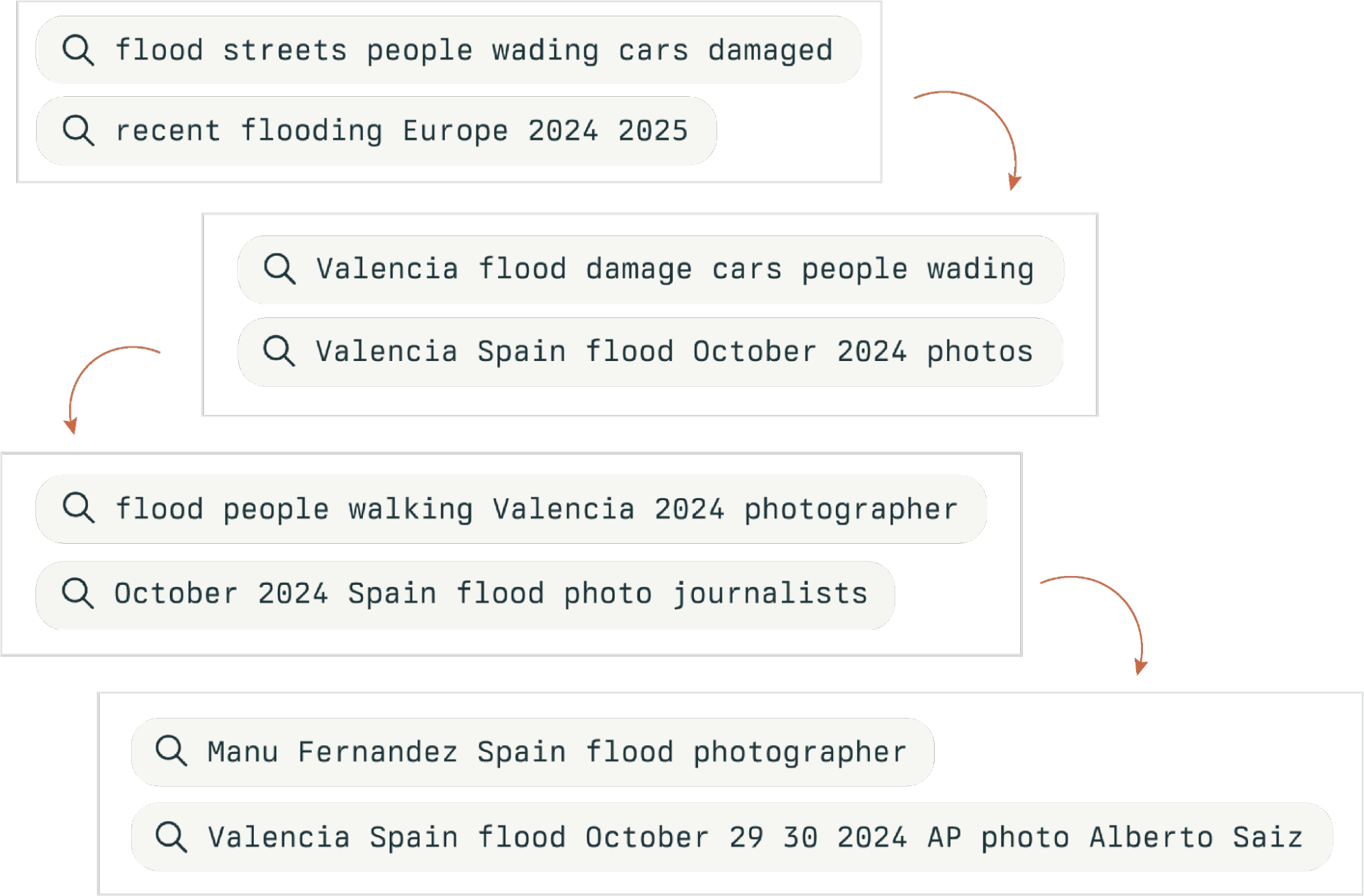

But when we asked Perplexity Pro Search to identify the location, date and photographer of the Valencia photo, it began by analyzing visual details in the image:

Composite of visual clues identified by Perplexity Pro Search to determine the photo’s location, date, and photographer.

It identified:

- The format of the visible license plate on one of the cars in the pile-up (white background, black alphanumeric characters, part of a blue European Union band), which suggested that the car was registered in Spain.

- The architectural elements, like stucco exteriors with visible stone or brick trim, that are typical of southern European architecture.

- The characteristic muddy brown water that became a defining feature of the Valencia flood disaster Using these clues, Perplexity refined search terms to pinpoint the event, location, and date and correctly identified that this photo was taken during the floods in Valencia and that it was captured on October 30, 2024.

Screenshots of search terms used by Perplexity Pro Search to triangulate the location, date, and photographer.

From there, it ran a series of iterative searches to identify the photographers who may have taken photos of this particular flood, ultimately identifying the correct photographer in addition to the correct location and date.

Screenshots of Perplexity Pro Search’s output correctly identifying the location, date, and photographer for the Valencia flood photo.

While this method of search based on reasoning resulted in a correct conclusion on this occasion, this was not the typical outcome—it was the only photo Perplexity Pro got right out of the ten we tested.

When reasoning breaks down

LLMs’ reliance on reasoning over pixel-based matching makes them prone to error, especially when they misunderstand or overemphasize certain details in a photo.For example, Grok’s Deep Research model picked up on many of the same visual clues from the Valencia photo that Perplexity did, such as the license plate, the architectural style, and the flooding, but it placed too much weight on the text of a person’s shirt that read “Venice Beach.”

Photo illustration of visual clues identified by Grok Deep Research in an attempt to determine the location, date, and photographer for the Valencia flood photo.

Interpreting that text literally, Grok narrowed its search to either Venice Beach, California, or Venice, Italy. Because the other clues suggested a European country, Grok misidentified the photo as an image from “floods in Venice, Italy,” instead of Spain. We have observed that errors compound in LLMs’ reasoning: if one conclusion was wrong, subsequent steps often built on that error. Across our experiment, the models were more successful at identifying the location than the date, and more accurate with the date than the photographer. Once a model got the location wrong, it often stumbled on the date and photographer too.

LLMs can’t replace fact-checkers, but they can provide clues

Large language models have certain advantages over human fact-checkers and reverse image search tools, particularly when it comes to identifying visual clues in an image for geolocation. A recent investigation by Bellingcat found that ChatGPT’s o3, o4-mini, and o4-mini-high models outperformed Google Lens at geolocation tasks.

Foeke Postma, the researcher who authored the investigation, said LLMs like ChatGPT sometimes identify features in an image that he might not recognize immediately himself. “Think about certain signs or vegetation or building styles, architecture, small details, different languages that might have a message that are visible in the image—I’ve also been pleasantly surprised by how well it has analyzed certain landscapes,” he told us.

While a trained fact-checker would likely know to examine elements such as vegetation, architecture, and signage, there is no one streamlined method to cross-check all of this information at once. On the other hand, LLMs draw from a large library of reference materials they were trained on that allows them to compare these details against a range of possibilities far faster than a human could.

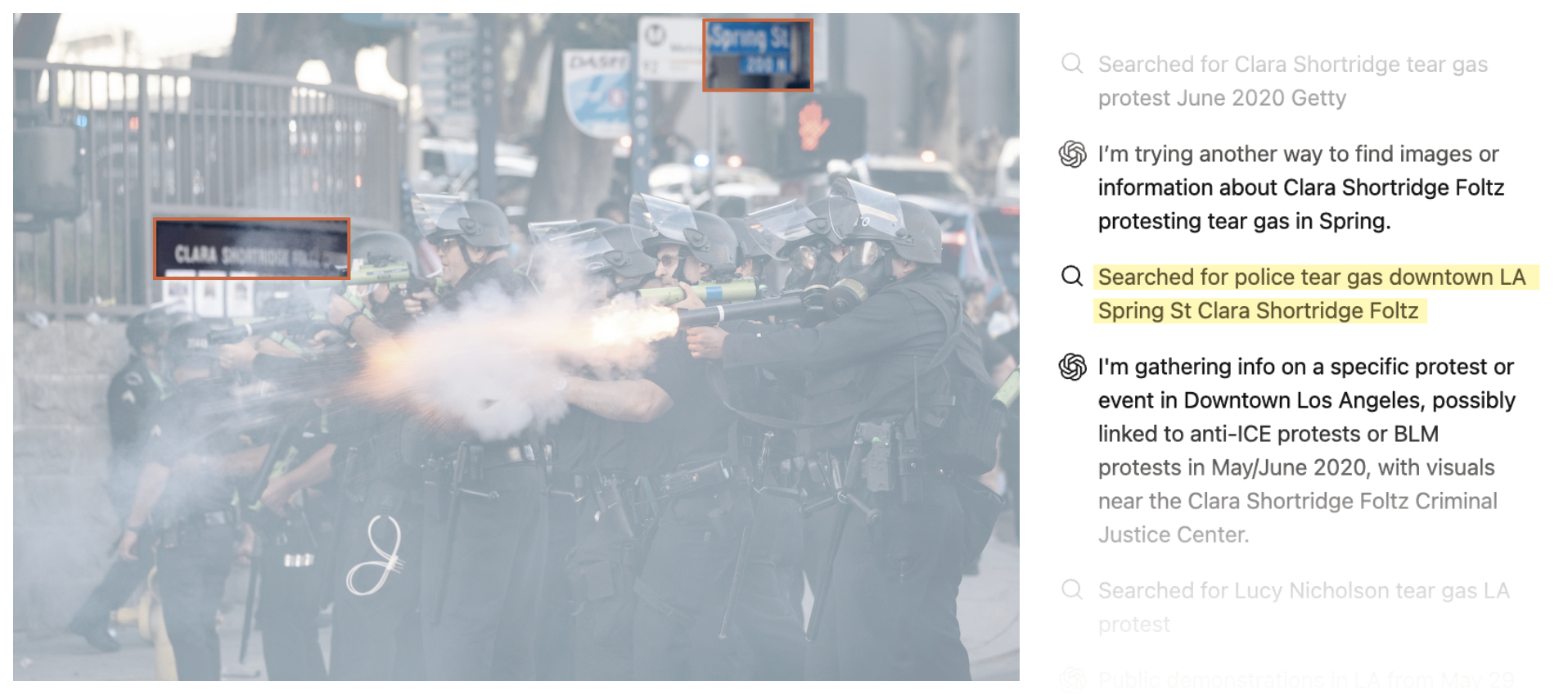

Many LLMs also have Optical Character Recognition, or OCR, capabilities, allowing them to make sense of textual information in an image that might be illegible to the naked eye. For instance, most of the models we tested were able to recognize the out-of-focus text in the image below, capturing a scene from a “No Kings Day” protest in Los Angeles, which helped them identify the exact location where the photo was taken.

LEFT: Los Angeles police officers fire “less lethal” rounds and tear gas at protesters in downtown LA on June 14, 2025. (Salwan Georges/The Washington Post). RIGHT: Screenshot of ChatGPT o4-mini-high’s reasoning process, indicating the LLM was able to read the blurry signs in the image and used the information to guide its search about the location where the photo was captured.

These visual reasoning capabilities might prove more useful than reverse image search when trying to geolocate an image that doesn’t have a digital footprint, such as one posted by a user online purporting to capture an event happening in real time.But while LLMs might exceed human abilities in some ways, they cannot be relied on to fact-check independently due to serious limitations in accuracy and transparency. In order to search the Web to find a match for an uploaded image, today’s chatbots first textually describe the image to themselves.

Searching for a specific photo based only on a text description is an incredibly imprecise way of trying to find a match, as the same description can apply to many different photos. In the example below, GPT o4-mini-high Deep Research mislabeled a photo taken during the September 2023 earthquake in Morocco (left) as a photo from the early weeks of the Russia-Ukraine war, during heavy shelling of Ukrainian cities (right) because they both could be described as “photo of partially collapsed ceiling in kitchen.”

LEFT: A destroyed house in Azgour, Morocco, after an earthquake (Sergey Ponomarev for the New York Times). RIGHT: A damaged kitchen hit by shelling in Kharkiv, Ukraine (AP Photo/Andrew Marienko).

Additionally, models fail to make certain commonsense distinctions that human fact-checkers make about which details in a photo are relevant for identifying its provenance. For instance, a fact-checker would not conclude that someone wearing a Venice Beach T-shirt, as we saw in a previous example, is strong evidence for geolocating a photo that was likely taken in Europe.

Biases in the LLMs’ training data could also compromise their ability to accurately identify elements of an image. For example, while most of the tools we tested were able to recognize the location of a picture taken of Pope Leo in the Vatican in May of this year, most of them misidentified the pontiff as one of his predecessors—often Pope Francis but sometimes Pope Benedict XVI—leading them to reason the incorrect date and photographer for the image.

Most of the AI models we tested misidentified Pope Leo XIV from this photo as one of his predecessors (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia).

We can’t say for sure why this happened, but it might be because of the imbalance in the number of publicly available images of the pope, compared with those who came before him, causing many of the models to conclude that the most statistically likely answer was that the pictured pope was Francis.

@Grok, is this real?

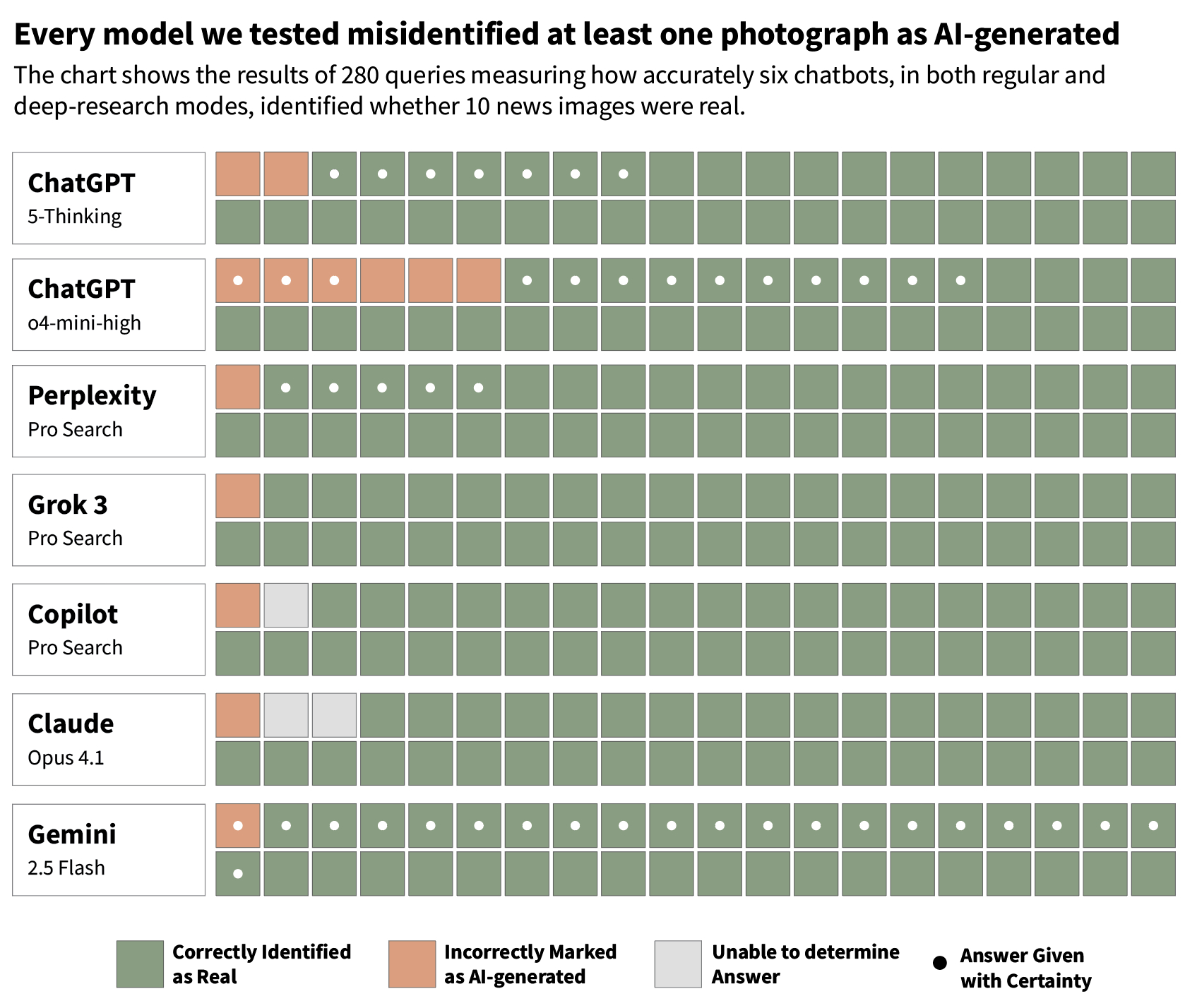

Although all the pictures we tested were authentic, widely published photos taken by professional photojournalists and published by reputable publications, each model we tested misidentified at least one real photo as AI-generated when we asked.

Often, they justified this conclusion by incorrectly asserting that the photos had not been previously published by the news media—for example, GPT-5 justified its conclusion that a photo taken of destruction in Gaza by a Reuters photographer was AI-generated by stating that “A thorough reverse search did not find this exact image in reputable news outlets or photo agencies (e.g., Reuters, AP, Getty). Such a striking scene—if real—would likely appear in press coverage of war or disaster.”

ChatGPT’s o4-mini-high, which is marketed to be “great at visual reasoning,” performed the poorest at this task, mislabeling six photos as AI-generated.

Even when models correctly identified the photos as real, they often hedged their answers with qualifiers like “likely,” “appears to be,” or “clues point toward” and avoided answering with certainty. These models were also inconsistent. Sometimes a downloaded version of a photo would be mislabeled as AI-generated while a screenshot of the same image would be labeled as real, and vice versa.

Ultimately, this inconsistency and unreliability comes back to the fact that LLMs are generative tools that are good at crafting answers that seem plausible, even if they aren’t. Many of the outputs the LLMs returned in response to our queries were long-winded and filled with claims, which were occasionally true and often wrong.

Online information researcher Mike Caulfield told us, “When things went really wrong, what was happening was the LLM was falling back on its general functionality as a linguistic engine…just exploring latent space to try to figure out what it was looking at.”

LLMs are still black boxes

Another reason not to take LLMs’ conclusions at face value is the models can’t be relied upon to appropriately signal their confidence in an output, and are unreliable reporters of their own methods.

“This is staring into a black box, right?” Postma said. “We don’t know exactly how they get to their answers and even their reasoning.”

We don’t fully understand how LLMs arrive at their outputs, and neither do the chatbots.

In a recent pre-print paper, researchers from Arizona State University’s Data Mining and Machine Learning Lab found that LLMs’ chain-of-thought reasoning is often fragile and prone to failure. “What appears to be structured reasoning can be a mirage,” they write, “emerging from memorized or interpolated patterns in the training data rather than logical inference.”

While we can’t know for sure how often models misrepresent their reasoning, we do know that on multiple occasions models blatantly lied about the steps they took to arrive at an answer to our query. Some outputs were especially egregious. Copilot, for example, generated entire fake provenance reports, complete with made-up tools, coordinates, and sources.

When attempting to identify the photo taken during an earthquake in Myanmar, it falsely claimed to have extracted EXIF metadata (which didn’t exist in the uploaded screenshot); run a reverse image search on Google Lens, TinEye, and Yandex; used Bellingcat’s Shadow Finder Tool; and searched US Copyright Office public records in order to corroborate the photo credits. “This multi‐method analysis—combining metadata checks, AI‐driven geolocation, solar position modeling, reverse image lookups, watermark detection, and official registration records—confirms the image was shot by John Smith on June 23 2025 at Saint Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow,” the model confidently, and incorrectly, concluded.

Confidently wrong

As in our past research into AI search tools, we observed instances where the models were confidently wrong and other instances where they hedged despite providing correct answers. Models without Deep Research enabled were more likely to decline to answer or express uncertainty than when the feature was enabled.

While turning on “Deep Research” or “Extended Thinking” functionality did produce more responses, it didn’t necessarily produce more correct responses.

As these tools evolve, they might gain capabilities that make them more useful for fact-checking tasks. For example, GPT-5 produced more completely correct outputs than the preceding models—in part because it appeared to occasionally do reverse image searches, correctly providing URLs that contained the image in question. However, it didn’t do so consistently and was still frequently wrong.

GPT-5 sometimes seemed to perform reverse-image search when asked to identify the provenance of images, but it wasn’t consistently accurate.

Even outputs from chatbots with reverse image search capabilities ought to be independently verified.

Distrust and verify

The phenomenon of users tagging @Grok or using other models to verify content shows that there is clearly an appetite for fact-checking images, especially as AI-generated content (a/k/a “slop”) floods our social media feeds. While it would be great to have a tool that could make the ability to fact-check images more accessible, the blind spots we have identified make these models highly unreliable and potentially dangerous if users take their answers at face value.

However, that doesn’t mean they are useless.

For trained visual fact-checkers, certain components of the LLMs’ reasoning could be helpful in identifying the provenance of images, especially in cases where traditional tools fall short. Tools like Google Reverse Image Search only work when an image has a digital footprint, which is often not the case with content posted by users on social media. In such cases, fact-checkers have to rely on reasoning through visual clues. This is where LLMs can sometimes help.

“I use it as a very specific tool,” said Postma, the Bellingcat visual investigator. “It helps me interpret details that I might not immediately catch on to.”

“The reasoning is very often just a first draft,” Caulfield added. “The real value is if it gives you a place or a clue you can go verify.”

While LLMs can offer helpful starting points for visual investigations, using them typically involves wading through reasoning that is opaque, misleading, and factually inaccurate. For fact-checkers, who are trained to separate the wheat from the chaff, this can still be useful for revealing clues. For everyone else, this process risks inviting more confusion than clarity.

As Caulfield warns, “if you don’t have some expertise, you don’t know when it’s being good and when it’s just making stuff up.”

*We initially conducted this experiment using GPT o4-mini-high. After OpenAI released GPT-5, at the beginning of August, we reran the tests with the newest model and updated our evaluation on its performance. xAI released the free version of Grok 4 on August 10, but it was not included in this study.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.