This research is generously funded by the Tow Foundation and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Introduction

Early in our first interview, a veteran news executive began the story of their interactions with technology companies over the past decade by taking a deep breath.

“You know,” the executive said, “it’s been a long, strange trip.”

It’s fitting that these were among the first words we heard in our study of the relationship between journalism and generative AI, the latest turbulent phase of the purportedly “post-platform era.” Failed products, misguided strategies, and an incompatibility with the demands of truth-based publishing have characterized many tech companies’ efforts to engage with news organizations, along with inadequate financial support that arrived sporadically and was tied to conditions. The most promising “innovations” in news have instead come from journalists and newsrooms finding strategies that protected them from the business models of platform companies. Nonprofit newsrooms have been forced into existence by Alphabet and Meta’s duopolistic grip on advertising revenue, while direct-to-consumer routes such as newsletters and podcasts have come into their own as social media and search platforms have deprioritized or even removed news.

The Tow Center for Digital Journalism has been researching the evolving relationship between platforms and publishers since 2015. Our 2019 report, “The End of an Era,” documented a period when publishers were coming to accept that the core premise of the social media era — that the future of journalism lay in targeting audiences on Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, Apple News, Google, and other platforms — was wrong.

In its stead came a renewed focus for publishers on fostering the direct relationships news organizations had formed with their most dedicated audiences, which they realized were also their best shot at sustainability. “The platform stuff was a distraction,” one publisher noted at the time. “It was a good lesson, an objective lesson in: Listen to your audience.”

Fittingly, that period is almost bookended by the transition from the so-called Death of the Homepage circa 2014 — characterized by headlines like “The homepage is dead, and the social web won — even at the New York Times” — and its rebirth as part of a renewed focus on leveraging publishers’ owned-and-operated platforms to foster direct relationships with their audiences through newsletters, apps, podcasts and, yes, websites.

A lot has happened in the meantime. For one, Google and Meta, Facebook’s parent company, whose deep involvement in the news ecosystem made them key protagonists in our previous reports, went from ramping up their respective big-money news initiatives and licensing programs — including the Facebook Journalism Project, Facebook News, the Google News Initiative, the Google Digital News Initiative, and Google News Showcase — to reducing their focus on journalism (Google) or withdrawing entirely (Facebook) in the space of a couple of years.

The initial displays of financial generosity came against a backdrop of mounting regulatory pressure around the world. In October 2020, Google CEO Sundar Pichai announced the company was committing “an initial $1 billion investment in partnerships with news publishers and the future of news” over three years through a new product called Google News Showcase. Not to be outdone, Facebook announced in February 2021 that it would commit $1 billion to journalism over three years.

Then the winds shifted. Facebook was first to show its hand in 2022, moving engineering and product resources away from its News tab and Bulletin newsletter platform, which was ultimately shuttered, along with Instant Articles. The platform also opted not to renew its News tab licensing agreements, and made substantial layoffs across its news division. The following year, it responded to the Canadian government’s passage of the Online News Act by immediately blocking access to news on Facebook and Instagram in Canada, as it had briefly done in Australia in 2021 to protest the proposed News Media Bargaining Code.

Google signaled its retreat from journalism through a series of similar moves in 2023, when the search giant responded to proposals in the California Journalism Preservation Act (CJPA) by threatening to pull links to California news sites from Google Search, pausing licensing arrangements with the state’s news outlets through Google News Showcase, and threatening to pause a planned expansion of its $300 million Google News Initiative across the country. Later that year, the company made substantial cuts to its news division.

Following its takeover by Elon Musk in late 2022, another major player in the social era, Twitter — which Musk rebranded as X — made a series of moves that were hostile to news organizations, including removing verification checkmarks from accounts that didn’t pay $1,000 a month for the platform’s new Verification for Organizations status or purchase enough advertising to qualify for free verification; labeling public service news organizations like the BBC and NPR “state-affiliated media”; and throttling the load speeds of links to news sites such as The New York Times and Reuters, as well as rival services including Threads, Instagram, Facebook, Bluesky, Substack, Mastodon, and YouTube.

As the old guard retreated, however, a new band of disrupters rose to prominence, pledging to harness a subset of artificial intelligence technology to revolutionize the information ecosystem. These newcomers included Perplexity, founded in 2021 to challenge Google’s dominance with an “AI search engine” that “searches the internet to give you an accessible, conversational, and verifiable answer,” and OpenAI, an AI company founded in 2015 with backing from the likes of Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, with a stated mission to “ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.”

Launched in November 2022, OpenAI’s flagship chatbot, ChatGPT-3, instigated an extraordinary boom in generative AI, taking large language models (LLMs), a hitherto relatively obscure technology mostly unknown outside the specialized fields of computer science, academia, and business, and thrusting it into the public consciousness almost overnight. According to Time, the tool had 100 million active users within two months, a landmark it reached seven months ahead of TikTok and more than two years earlier than Instagram had. As early as December 2022, ChatGPT’s meteoric rise “led Google’s management to declare a ‘code red,’” according to the New York Times. In February 2023, a month after extending its multibillion-dollar investment in OpenAI, Microsoft announced that OpenAI’s generative AI technology had been integrated into its Bing search and Edge browser products.

The launch of ChatGPT also serves as a useful — albeit rough — starting point for the (generative) AI era of the platform-publisher relationship. Generative AI intersects with journalism in a number of ways, some of which highlight key distinctions from social media. The first — as anyone who has attended a journalism-oriented conference or training session or seen a research proposal or school curriculum since late 2022 will be acutely aware — centers on the push to use generative AI tools for tasks including, but not limited to, analyzing large datasets; converting news outputs into different formats; translation; headline and summary generation; and drafting copy for emails, internal reports, or social media posts.

The second, rather more contentious intersection — which is the central topic of this report — centers on the fact that the text data used by AI companies to train the LLMs that underpin their generative AI products includes a significant amount of published journalism. The Times, for instance, found that its content accounted for 1.2 percent of a recreated version of the dataset used to train OpenAI’s ChatGPT-2. What’s more, among the applications being developed with this scraped data are generative search products that summarize web content, such as news articles, on-platform, reducing the need for users to click through to the source material. The pitch from Perplexity, whose founders included former employees of Facebook and OpenAI, promises “instant, reliable answers to any question with complete sources and citations included. There is no need to click on different links, compare answers, or endlessly dig for information.”

This appears to be true: As of May 2025, many news publishers are experiencing sharp declines in referral traffic from traditional search engines, particularly Google, which has been expanding its AI Overviews feature and experimenting with AI-only search results. Meanwhile, data from Comscore and Similarweb indicate that generative AI platforms like ChatGPT and Perplexity have yet to emerge as significant sources of news traffic, contributing only a negligible share of visits to news websites. A February 2025 report by TollBit, a marketplace for publishers and AI firms, found that AI search bots on average are driving 95.7 percent less click-through traffic than traditional Google search. This drop may stem from users’ growing preference for “zero-click” experiences; a Bain & Company survey published the same month found that 80 percent of consumers rely on AI-generated summaries or search page previews without clicking through at least 40 percent of the time. As Axios reported in April 2025, the decline in traditional search referrals is “unlikely to be offset by new AI search platforms in the foreseeable future, if ever.”

AI companies’ recent rollouts of generative search tools that promise fresh, reliable, up-to-the-minute content highlights a key distinction from the social era, insofar as it undermines tech companies’ ability to claim that they don’t need (or want) news output on their platforms. Explaining Meta’s decision to block news from Australian outlets in 2021, Nick Clegg, Meta’s VP of public affairs, said, “We neither take nor ask for the content for which we were being asked to pay a potentially exorbitant price.” The recurring line in Clegg’s statements about the company’s retreat from journalism in Europe, Australia and the United States, and Canada was: “We know that people don’t come to Facebook for news and political content.”

AI companies need reliable, verified data to train and ground LLMs, and have scraped vast quantities of news content to do so. As Jessica Lessin, founder of The Information, argued, “It turns out that accurate, well-written news is one of the most valuable sources for these models, which have been hoovering up humans’ intellectual output without permission.”

That genie can’t be put back in the bottle, Clegg has acknowledged more recently, “given that these models do use publicly available information across the internet.” Therefore, the negotiating position is no longer that they don’t need or want news output, but that they don’t need to ask or pay for news content.

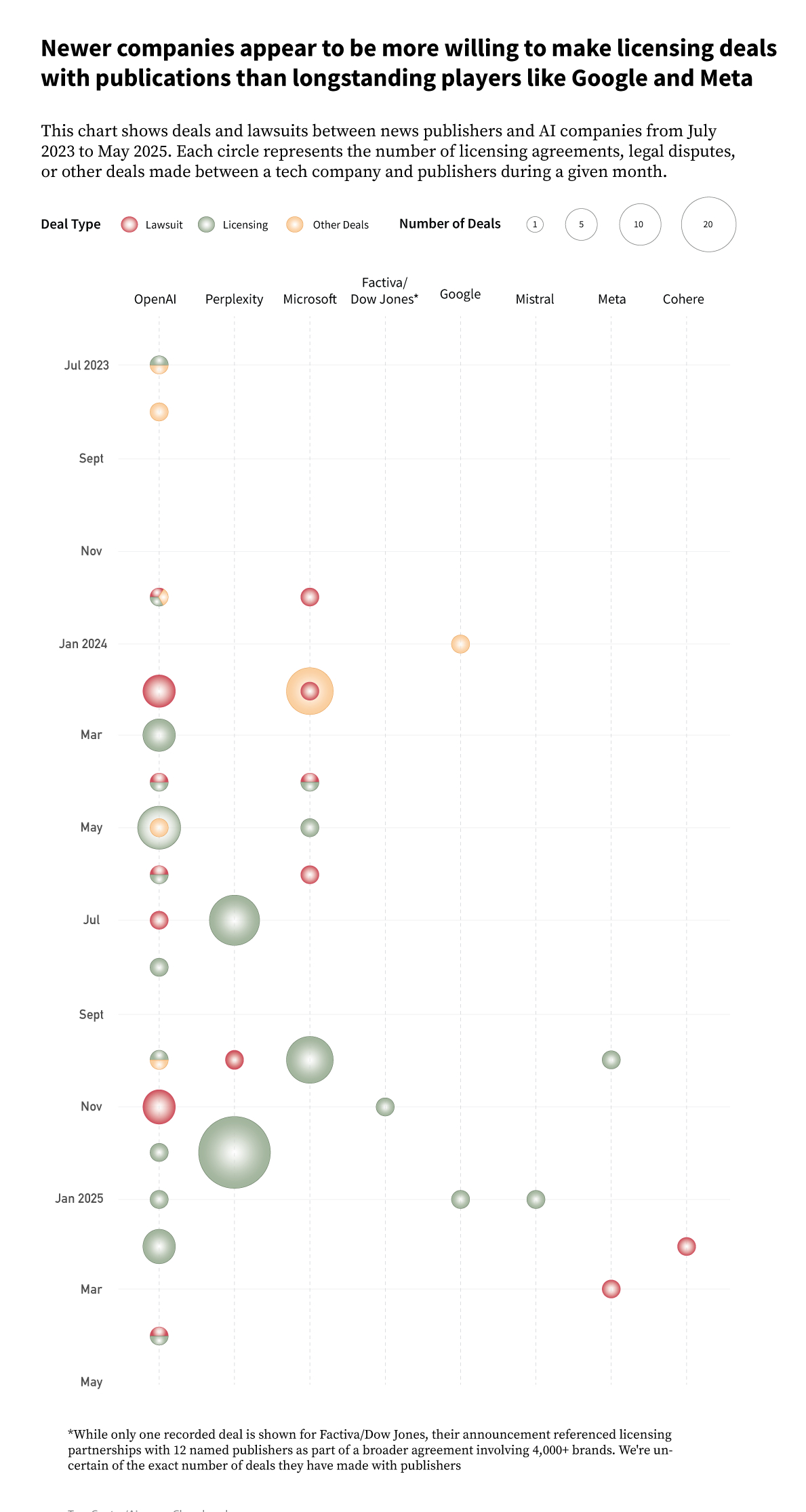

Among news organizations of the view that AI companies have infringed copyright and stolen their intellectual property, a few have weighed whether to litigate or seek licensing agreements. The Times’ 2023 copyright infringement case against OpenAI and Microsoft — OpenAI’s primary investor, exclusive cloud provider, and strategic partner — is the highest-profile example of the former, while several dozen publishers have entered into licensing agreements with OpenAI or revenue-sharing agreements with Perplexity. But most news organizations are stuck watching from the sidelines. Meanwhile, Google and OpenAI are attempting to circumvent the legal battle altogether by lobbying the Trump administration to weaken copyright restrictions on AI training and codify a right for U.S. AI companies to train their models on publicly available data largely without restriction.

While upstarts like OpenAI and Perplexity have certainly caused a stir, established names such as Microsoft, Apple, and Google have strained to portray themselves as allies of the news industry while facing tough questions about their handling of publishers’ intellectual property. Microsoft, for example, which has historically paid to license news for its MSN portal and positioned itself as the friendly alternative to Facebook and Google when the News Bargaining Code was making its way through the Australian courts, has cozied up to publishers with “several collaborations with news organizations to adopt generative AI,” even as it is being sued by multiple news organizations that accuse it of infringing their copyright in order to create that very same generative AI technology.

All told, it’s fair to say the AI era of the platform-publisher relationship hasn’t gotten off to the smoothest start, but the same could be said about every previous era. “Generative AI has increased the gravitational pull” of some platforms, the news executive quoted at the top of the chapter noted, while others, like X, have less sway. “OpenAI didn’t exist but now is a thing; Microsoft was less of a player and is more of a player,” the executive continued. “The challenge that we have right now is that news, as an industry, tends not to learn terribly well from our past experiences and mistakes.”

This assessment neatly encapsulates a motivating force behind this report. Certain aspects of the AI era are new, while others are eerily familiar; there are opportunities for both news outlets and tech companies to apply the lessons of the past, but structural similarities mean that some mistakes may be repeated. (Sitting outside the scope of this report are questions about the safety and ethical nature of the use of these tools in newsrooms, as well as the impact the widespread adoption of generative AI tools for both content production and consumption might have on the health of the information ecosystem.)

Conscious that this era — and indeed, AI technology as a whole — is in its nascency and critical episodes are yet to fully play out, the primary goal of this latest iteration of our ongoing study is to assess the health of the relationship between platforms and publishers during this early but already stormy period. To achieve this, we conducted 34 semi-structured interviews with representatives from the news and technology industries from the U.S. and Europe: 24 news executives, editors, product managers, and newsroom AI specialists; six former platform executives; two representatives from AI companies; and two AI experts. All interviewees were promised anonymity in accordance with the protocol approved by the Columbia University IRB (Protocol Number: IRB-AAAV1429). Given our purposive sample, no claim is made to generalizability. Instead, we explore the key themes that emerged from our conversations, which took place between May and October 2024 and lasted 30 to 75 minutes each.

This report is a survey of the relationship between publishing companies and the technology and platform companies that by their actions and products shape the field of journalism. Outside the scope of this report are questions about the safety and ethical nature of the use of these tools in newsrooms, as well as the impact the widespread adoption of generative AI tools for both content production and consumption might have on the health of the information ecosystem.

The Structure of this Report

This report contains six chapters. In Chapter 1, we present a brief overview of how interviewees characterized the status of the relationship between news publishers and technology companies as of mid-to-late 2024. While we sought to avoid repeating the well-documented history of when, how, and why the relationship between platforms and publishers disintegrated, this chapter provides important context about the extent to which news workers’ dealings with AI companies are being shaped by past experiences.

In Chapter 2, we begin our exploration of how generative AI has started making its mark on news organizations. Rather than duplicate excellent work that has already been done exploring specific use cases and workflows, we focus instead on interviewees’ attitudes toward the utility of generative AI; the extent to which they felt it was delivering on its promise; the levels of understanding about the technology in their organizations; and the manner in which that understanding shapes strategic decisions and demands.

In Chapter 3, we offer a detailed discussion of how interviewees are thinking about some of the key issues stemming from the rise of new and emerging third-party platforms that use generative AI to summarize journalism, such as Perplexity; OpenAI’s search tool, which was integrated into ChatGPT in October 2024 after the conclusion of our interviews; and the AI Overviews that Google has begun integrating into its market-dominating search platform. We begin the chapter by addressing the elephant in the room: the extent to which unresolved issues around copyright and intellectual property cast a shadow over every aspect of our conversations. In particular, we discuss an aspect of this knotty debate that recurred throughout our interviews: the speed at which the respective parties may want to seek a resolution. This is followed by a discussion of other common themes pertaining to disintermediation, the new value exchange, audience traffic, and data.

Chapter 4 is dedicated to a discussion of licensing deals, one of the foremost ways in which AI companies, most notably OpenAI, have started to formalize relationships with news organizations and indicated that they see some financial value in journalism. Having discussed the broadly positive view that, for all their limitations, these early deals set an important precedent in regard to journalism’s financial worth and the need to pay for access, we explore interviewees’ attitudes toward these arrangements, which run the gamut from “a really scary moment for journalism” to “it could be free money.” To round off Chapter 4, we touch on some of the nonfinancial aspects that interviewees identified as key considerations in any formal arrangements with AI companies.

In Chapter 5, we delve into some of the deeper issues that emerged regarding the relationship between AI companies and news organizations, such as a lingering sense of betrayal and resentment among publishers exhausted by earlier dealings with technology companies; the extent to which disruption from the highly competitive arms race around generative AI is already having real-world implications for some interviewees and unsettling others; how incompatibilities between platforms and publishers could spell trouble if they go unaddressed before the AI era hits full swing; concerns about wider issues on the horizon; and recurring calls for greater collaboration both within journalism and across the two industries.

Finally, in Chapter 6, we reflect on our findings and unpack the key areas that seem primed to determine the next phase in the uneasy marriage between platforms and publishers.

Platforms and Publishers in 2025: A Bird’s-Eye View

Having absorbed the well-documented lessons around tech platforms’ unreliability as partners (crudely, that monetization, traffic, audience, visibility, and publishers’ access to representatives can fluctuate or disappear at a moment’s notice — if they existed in the first place), publishers have long viewed strong, direct relationships with their audiences as vital to their hopes for a sustainable future, ideally through their owned-and-operated properties.

Speaking of a historical pitfall that contributed to this reprioritization and emerged as a concern about third-party news summarization platforms (see Chapter 3), a news executive said, “A lot of the audience that we could have built in spaces that we controlled, we built elsewhere and then we rented, in a sense, and then the landlord evicted us and so we didn’t get to keep any of those improvements — they were all in a space we didn’t own.”

But despite platforms’ checkered history and talk of a post-platform era, an early theme to emerge in our interviews was that many of the platforms that mediate publishers’ relationships with their audiences remain unavoidable. An interviewee with deep experience on both sides of the platform-publisher divide typified the views of many: “I don’t think there’s any way around the platforms. The platforms are … where the audiences are. Where there are new audiences, where there are old audiences. … So as a publisher, you have to be there.”

Another news executive said that platforms today are crucial for publishers’ efforts to “be part of a person’s media diet. … It’s about finding those new audiences, reminding them that our brand exists and that we have great things to say, and it’s about learning how to translate our brand and tell stories in new formats. That, I think, is a critical level of experimentation.” The question, they continued, therefore becomes, “How do we utilize these places where we know there are large audiences and try to get them to engage with us?”

Continuing a central theme from our last report, most of the publishers we spoke to in summer 2024 said they had refined their distribution strategies to focus on the handful of platforms that make the most sense for their brands. Highlighting the extent to which new and existing audiences factor into many platform strategies, a news executive with deep experience negotiating platform partnerships summarized their key requirements with a three-point checklist:

- Is it a healthy and safe environment for our brand and audience?

- Can we use it to generate direct relationships with our audience in our own environment?

- Is there a reasonable value exchange between us and the platform, i.e. are we getting enough out of whatever we put in?

Given tech platforms’ ongoing, albeit uneven and reconfigured, importance to news, a recurring sentiment among publishers — including some whose organizations have been stung by misplaced optimism about platform partnerships — was the importance of maintaining open lines of communication with technology companies to understand how emerging innovations and priorities could affect their businesses and the ecosystem at large.

One news executive described their current approach as “more like a defense and offense strategy all at once.”

“How do we play defense with these guys in a way that’s not gonna turn us off from the internet?” the executive asked. “Obviously they’re still crucial partners and crucial places where the audiences are spending a lot of time, and we’re going to have to find the right ways to work with them, but [only] in a way that’s ultimately going to be additive to the business and strategic.”

The view that it is better to be on the inside, gathering knowledge about the prevailing direction of travel, than on the outside playing catchup was echoed by an executive from a large international subscription-based outlet, who said, “Our experience with technology has been that if you shy away from it and ignore it, it’s not going to do you any favors. If you try [to] lean into it and understand what it’s about and what it’s doing, then generally you’re going to be in a better place to make a smart decision.”

A news executive who moved into the nonprofit sector after many years with for-profits captured the potential risks of engaging with tech companies when they said: “An approach I’ve always had to conversations with platforms has been to say yes.” But yes to what? The executive continued: “Go be in the room and hear what’s going on and hear what they have to say. With OpenAI and Google, that outreach has already begun, so if that continues, then the conversations are something that I welcome, particularly to understand where they’re headed. But as far as partnering goes, I would have more follow-up questions than a younger me did, and would go into it with a bit more trepidation now.”

The bluntest articulation of this perspective came from an executive of a legacy publication who said, “I think you have to engage, because if you’re not engaging you don’t even know what these deals are. It’s better to be engaging than to stand back and say, ‘I’m having nothing to do with this.’ I don’t think we have the luxury of that. We may still get fucked in the process, but it would be better to at least understand where those things are going and to be able to utilize that.”

Increasingly, however, journalism partnership teams at some of the biggest players have shrunk or been disbanded, meaning that many news organizations no longer have anyone to talk to at the platform companies. An AI leader at a large international legacy news organization with good access to platforms acknowledged that their company was an outlier: “Relative to the wider industry, our relationship is a pretty good one. I say that because we have a direct line into different platforms, which is quite unusual.”

More typical was the frustration expressed by an executive news editor at a major international outlet who had come to accept that technology companies tend to pick up the phone only under specific circumstances. “If you don’t have something that they are explicitly looking for, you will be — to be blunt about it — probably ghosted,” they said. “It is incredibly difficult to find a person in any of these technology companies right now who wants to just talk about news or distribution.”

There was a feeling that AI companies’ need for verified, high-quality, real-time information to train their LLMs might motivate them to improve their relationships with news organizations. Interviewees from AI platforms claimed to be conscious that work is needed to prevent the kind of hostility between technology companies and the news industry that prevailed during earlier eras.

“We have to start by acknowledging that tech needs journalism, and journalism needs tech,” said a current platform leader with a journalism background. “We have to recognize the unique role that journalism plays in society and in the world and in our own products. If we create economic conditions or functional conditions that pose threats to journalism, that inhibits our ability to have a product that’s informed by good information and put it out there. So we do have common ground there. Are there questions that we haven’t resolved yet in that discussion? Absolutely. But I think if we can remember that we need that symbiotic relationship, hopefully that’s what powers the conversation into the next chapter.”

Similarly, a representative from another prominent AI player insisted that their company’s future prosperity is intertwined with that of the news industry. “We realize … we need to work very closely with the publishing industry, because our success is tied directly to the success of a thriving journalism and digital publishing ecosystem — AKA, we know that journalists produce high-quality verified facts, and in order for [our tools to be able] to answer some of [our users’] questions, we need the continual production of that type of information. Basically, there is no world in which [AI platform] is successful but publishers are not.”

Moreover, they hoped to avoid the ephemeral sugar rushes that defined earlier phases of the platform-publisher relationship. “There was a lot of short-term thinking and trying to chase the money, because newsrooms were really having a challenging time, so they probably needed to go where the money was,” the AI representative said. “But there was not a lot of long-term thinking. And one of the best things about my time at [previous platform], and what I’m trying to infuse into my role here at [AI platform], is really trying to think more long-term and build things that will scale, rather than the short-term programs or playbooks.”

While this is an admirable position, the broad trend at tech companies toward eliminating or shrinking news partnership teams, making them an even smaller cog in a much larger machine, will necessarily limit their effectiveness. As a former platform executive admitted, “If you’re operating at scale as a big tech company, you’re trying to do the right thing,” but ultimately “all the structures … end up being the least worst ones that you can do.”

The Generative AI Era

OpenAI launched ChatGPT-3, the chatbot widely credited with bringing generative AI into the public consciousness, at the end of November 2022. By the time our interviews began some 18 months later, the initial hype around generative AI had largely subsided. Instead, we typically found news workers trying to temper their weary disenchantment with optimism that the youthful technology might still deliver on its promise.

One CEO’s assessment crystalized the general mood: “There was this unbelievable enthusiasm, obsession, curiosity, early adoption of the platforms and tools. And now I think there’s a bit of disillusionment because [AI companies] don’t seem to have really cracked a genuinely viable product or genuinely transformational use case.” However, this person noted that user behavior or the application of these technologies might change or be disrupted in years to come.

An executive at a major global news organization put it slightly differently. “I think generative AI technology is so transformational, and I’m not even sure the creators of the technology fully understand what the applications are, or the primary use cases,” they said. “It’s a clever piece of technology, and everyone is searching for the transformative, once-in-a-generation idea that is going to propel it into the public consciousness. I haven’t seen it yet.”

At the more cynical end of the scale, a policy executive at an international newspaper who lamented the time, energy, and money being poured into “chasing this illusion that one general-purpose technology is going to solve all of the industry’s problems,” said: “Never have I seen so many innovations that were already ongoing being trumpeted as completely new [as I have] under the banner of generative AI, just because it’s highly sexy and the thing that everyone wants to talk about at conferences. We spend so much time and energy and money on these technologies because people are chasing the hype.”

While most interviewees could reel off a litany of ways their organizations are using generative AI behind the scenes, many also noted that the immaturity of the technology means any larger impacts on their workflows, practices, products, and businesses will only come into focus later. “It’s still such early days that it’s really hard” to predict the potential use and impact of the technology, an executive from a major legacy publisher said. “There’s just a lot of noise in the system, so it’s hard to dissect it all and for us to say what we need to do differently.”

One thing that quickly became clear is that many news outlets are investing significant time and energy in controlled experimentation with generative AI, using it for a range of tasks from transcribing interviews, drafting headline ideas, and summarizing articles, to repurposing and reformatting existing work, building interactive bots, and optimizing content distribution. But while a large majority of interviewees from the publisher side could reel off a range of such internal experiments, most stressed that even the most promising were unlikely to move to production any time soon, if ever — particularly where they were audience-facing. They considered the technology too unreliable to risk the damaging implications for brand and audience trust of publishing confabulated nonsense.

“The problem,” noted an executive at a large international public service news organization, is that the AI output “has to be perfect.” Their outlet, they added, cannot, for example, “have a story about [our] chatbot giving incorrect or malicious or harmful advice to a child. Other companies might be able to, but we can’t.”

An executive from a major international legacy newspaper brand said, “[Given] the unreliability of large language models, [their] propensity … to hallucinate means you’d have to be either a very brave or a very foolish publisher to put your brand reputation in jeopardy at the moment by putting AI technologies in a position where they’re publishing stuff to consumers that suggests that it’s original journalism.” Yet a number of publications have gotten into hot water in recent years for publishing low-quality AI-generated content.

Even in the rare instances when interviewees could share audience-facing examples that have made their way to publication (complete with prominent notices about the experimental nature of the tool), they still emphasized the guardrails that had been implemented to minimize risk. Describing the design of a chatbot that draws on the outlet’s deep archive to answer questions about a specific topic, an AI leader at a large legacy outlet said it had been important to identify a “safe” topic because in that case, “[g]etting something slightly wrong or framing it slightly wider rather than narrower … you’re not likely to have a real delta between what the asker asked and what we respond with. But [if] you look at nuance like that around a political issue, it can be really problematic.”

Adding to brand integrity concerns and the unreliability of foundational models, interviewees also pointed to lack of audience appetite as a reason for prioritizing experimentation instead of racing to production. An executive at a global public service news outlet said, “We are an organization that relies on trust. You can’t be a public broadcaster unless you protect your trust with the audience. And the audience isn’t yet at a place with generative AI where it believes it is necessarily a good thing. Until audience expectation and audience attitudes to generative AI move, there is too much risk for a public broadcaster like [ours] in going too quickly into that space.”

For organizations of this mindset, there is a fine balance between avoiding the risks that come with premature moves and being overly cautious and getting left behind. As this executive said, “You get into quite an interesting strategic conversation, which is you don’t really want to be the leader in the space, you don’t want to be the first mover — you probably want to be the second or third mover. Because you want to learn and absorb learning before you deploy. Because in a trust-based organization like [ours], the risks are too high to pioneer.”

In the absence of audience demand, the CTO of a for-profit outlet described experimentation partially as a means of preparing for a future uptick: “Internally, we have a lot of discussion that is like, ‘When do we take it from experimentation into heavier product development builds or into making it a first-class citizen?’ But the revenue incentive isn’t there yet. Our clients aren’t begging us for generative AI tools just yet, right? So it feels like the time is right for us to continue doing experimentation, so that’s what we’re doing.”

Despite their personal reservations, this technologist added, “There are definitely folks in our organization, especially senior leadership, that honestly believe that this is an iPhone or electric car kind of moment. And they feel it is important we be familiar when the curve goes more hockey stick, right? So when the adoption rates start to soar and when our [subscribers] begin to demand features from us, we want to be ready to go.”

Indeed, interviewees whose organizations had the capacity to experiment with generative AI described a wide range of rationales behind their organizations’ forays into the technology. Some had dedicated research and development teams that recognized unique opportunities in the new technology, having experimented with machine learning and artificial intelligence. For others, responses ranged from sharp pivots motivated by belief that the technology will live up to its transformative billing to curious experimentation for which generative AI was almost a solution in search of a problem.

An audience executive at a for-profit digital native recalled, “There was a really interesting moment in a meeting where it became clear that the policy had just flipped overnight. Previously it had been, ‘Hey, we’re researching and approaching this with caution,’ and all the usual language around that. Then overnight it was, ‘Your 2024 goal is to use AI as much as you can and to learn as much as you can about it in that way.’”

A significant number of interviewees highlighted uneven levels of knowledge about generative AI within their organizations, particularly among the most senior decision-makers. “Within news organizations, there is a lot that we don’t know,” an executive at an international nonprofit news outlet acknowledged. “Part of it is because it’s really complex what generative AI platforms do, and so for the less technical decision-makers, there’s a much greater hill to climb to understand exactly what’s going on there. I think that most of us, beyond the people who are creating these platforms, don’t actually really fully understand what will happen down the line, or what the leadership of an OpenAI or a Google has in mind for these platforms.”

An interviewee with deep experience on both sides of the platform-publisher divide said, “If you talk to an executive in a publishing house about AI and how it works, what it enables us to do now, and what it could look like in just two years’ time, it’s just so mind-boggling [to them] that they can’t follow along.”

In fact, a number of conversations illustrated how this mismatch in knowledge has already created headaches for newsroom staff. Raising a complaint reminiscent of some of the industry’s earliest web experimentation, an AI strategist at a news agency said, “We’re getting our direction from the top down. And I will say the top is not well informed. So the use cases they’re asking us to pursue are not very good ones.” While AI can work well for translation, it’s “a little dangerous” for a large news organization to use it to write headlines or summaries, they said. “They’re not letting our team lead on this. They’re instead trying to lead it in a way that’s managed — probably overly managed.”

A CTO described the balancing act required to respond to the sometimes vague and/or impractical demands of upper management while moving forward with day-to-day development work: “When I talk to my teams about this, one of the things I say to them is, ‘Look, you need to take these pushes from our execs and from the boards seriously, but not literally. They don’t know how to ask you precisely what they want. They’re telling you there’s a problem here.’ And I believe that there are real problems to be solved that generative AI and, more broadly, autonomous agents working on my behalf can solve. It’s our job to figure out versions of that that are sensible, and not boil the ocean or build really dumb products.”

Elsewhere, a digital director at an international outlet described misplaced suggestions to delegate content creation tasks to generative AI. “It’s usually around e-commerce, saying, ‘We need 10 articles about lipstick, or about foundation. That’s really dull for a person to write, so just get an AI to do it.’ But that’s going to be really dull for a human to read. And it’s not going to rank, because [Search Generative Experience] is going to squeeze it.” (Search Generative Experience was Google’s name for what became AI Overviews when generative AI summaries were introduced as an experimental feature in May 2023.)

Some interviewees also suggested that the uncertainty about how generative AI might impact news publishers partly stems from a lack of clarity on the part of AI companies themselves. An executive news editor at a major international outlet said, “No matter what anyone will tell you, I don’t think that they have the necessary insights yet to know where all of this is truly going. I don’t think we know what the near future exactly looks like.” Another executive said, “Everyone’s playing. Everyone’s making it up as they go along.”

News Summarization and Generative Search

While the publishers we interviewed said they were hesitant to put generative AI products in front of their audiences, the industry at large is keeping a watchful eye on third-party news summarization products and platforms. Generative search products that use AI to summarize one or more pages (including news articles) instead of returning links were making headlines throughout our data collection period:

- Google made AI Overviews central to its Welcome to the Gemini era presentation in May 2024;

- In June 2024, Perplexity launched a summarization product called Perplexity Pages that attracted cease-and-desist letters from publishers accusing the company of plagiarism;

- In July 2024, OpenAI announced a temporary prototype called SearchGPT, a real-time search product that would later be integrated into ChatGPT.

Since then, more AI companies — including DeepSeek and xAI’s Grok — have rolled out their own real-time search products.

A number of interviewees said they envisioned strong consumer demand for third-party news summarization products. But as one executive put it: “There is a dimension of behavioral change that’s necessary for generative search to really lift and fly.”

That change, according to one news executive, “slightly depends where the generative search is taking place. I don’t think Google introducing a generative search product into their existing search is going to particularly require a behavioral change. But it will require a behavioral change for someone to go, ‘Actually, I’m not going to use Google. I’m going to use ChatGPT search.’ There’s a bit of consumer mindset change involved here.”

To some degree, Google and Apple, in particular, could play outsized roles in driving these changes. For example, Google’s rapid integration of AI Overviews into the top of its market-dominating search engine has undoubtedly affected user expectations and behavior; AI Overviews have been rolled out to more than 100 countries since our interviews were conducted. Apple, meanwhile, currently has a lucrative deal to make Google the default search engine on its iOS mobile operating system, but has teamed up with OpenAI to power the Apple Intelligence products incorporated into iOS beginning in October 2024. (The default inclusion of Apple News on iOS and MacOS devices reportedly created 145 million monthly active readers, as of April 2024, and drove habits such as swiping for curated stories from the home screen.)

Some interviewees were prescient enough to see that search changes could be widely and quickly adopted, with far-reaching ramifications. “The thing that’s made me think everything’s going to change is I think search is going to change quite quickly,” an executive from a large international outlet said. “That worries me for lots of reasons, mainly about media plurality. The idea of AI being a single source of truth is, I think, profoundly disruptive. It’s disruptive to commercial models, and it’s disruptive in terms of democracy and choice of media sources.”

While the march toward generative search was expected to cause significant disruption, many interviewees stressed that adapting to new technology and platforms was not novel. In fact, some questioned why generative AI was afforded such attention in this regard.

An AI leader at an international broadcaster we interviewed in August 2024 told us that though generative search was something they thought about “a lot,” they felt that some of the predictions about its impact seemed hyperbolic: “We’re having industry analysts talking about 50 to 80 percent reductions in traffic within 12 months, the decimation [of traffic]. A lot of that was really unhelpful because it wasn’t founded on any understanding of the technology, or where the companies may go, or any data. It’s really unhelpful, but got a lot of traction.”

An AI leader at a major U.S. news organization suggested that publishers’ concern about adapting to the rise of generative search was partly driven by lingering resentment about having to shapeshift to match the whims of platform companies: “There’s a lot of fear [about generative search], not least because we’ve all existed in this news ecosystem for the past decade. I’ve been at [news organization] where changes that platforms make radically shift user behaviors. We were all there for Facebook traffic and then Facebook traffic went away. So I suspect the fear is not … tied to the AI piece so much as the platform and user behavior piece of it.”

For others, the most illuminating point of comparison goes back even further than the peak Facebook years in the mid-2010s. In fact, a number of interviewees argued that the emerging AI era shares most with the pre-platform era at the dawn of the 21st century.

“I think that we need to think carefully about what the media world looked like in the first decade of the web. … We were building digital audiences, but we did not really have social media yet per se,” the CEO of a local nonprofit news outlet reflected. “That’s a very illuminating decade because that is essentially what we’re going back to right now, where the social platforms, they’re just not our friends at all. We’ve already reached that post-social era, if not the post-search era. And so in this post-platform era, we have to look at that first decade.”

An executive from a global news outlet drew the same comparison. “There was a sort of period zero in publisher-platform relationships that was a period of disintermediation. It was a period where it seemed like a good deal to give your journalism to a platform and say, ‘You go ahead, you make a business model out of this and maybe send me some traffic or something.’ And it turned out that’s not a great equation.”

This comparison has been made in some reporting of contemporary deals. “Publishers want to avoid repeat of early internet era when US giants built ad-based empires using freely available content,” said a Financial Times subheadline above reporting on OpenAI’s deal with Axel Springer. According to the story, “Executives have focused for the past few months on ensuring that, unlike in the early years of the internet, Big Tech fairly compensates the media industry.”

Disintermediation

Discussing the opportunities and concerns of the current moment, an executive from a global outlet that has struck a deal with an AI company said, “Key risks, I think one word would describe it best: disintermediation.”

Put simply, this refers to the way third-party platforms can bypass news organizations, essentially cutting out the traditional intermediary between a journalist and their audience. Offering consumers condensed summaries of journalism diminishes their need to visit the original source and weakens the relationship between publisher and audience member.

Key subthemes in this regard related to:

- Brand integrity;

- Brand dilution;

- The need to double down on direct relationships with audiences.

Brand Integrity

As we noted in Chapter 2, few interviewees expected to move even their most promising audience-facing generative AI experiments into production any time soon, if ever. This caution typically arose from the view that the unreliability of the technology — particularly its propensity to generate falsehoods — is too potentially damaging to publishers’ reputations and hard-won audience trust. Related concerns about third-party products attributing inaccurate, confabulated, or otherwise harmful outputs to unsuspecting news brands featured prominently in conversations about generative search platforms, as did brand integrity concerns about adjacency to undesirable content.

On the latter, one executive at a major international outlet said, “The big concern, obviously, is around the remixing of your journalism and then the adjacency of sitting next to sources that maybe don’t have those same standards and practices that organizations with high levels of trust and high-quality methods of doing journalism have.”

The omnipresent risk of unintended, uncontrollable repercussions arguably heightens the need for strong, direct lines of communication with platform representatives. As one executive news editor at a major international outlet put it, “You’ve got to constantly be in the technology companies’ ears about this because they … are not making any of this [technology] with the use case of news in mind. Search has never been about news. … They are making these tools with the use case of connecting a person with a product or service that will then be sold, and we’re just in the mix of things that are being sought or looked for by the audience.”

Some interviewees from larger outlets said they were seeking to leverage relationships with AI companies to have input on shaping nascent generative search products. An executive from a major legacy newspaper said, “There are plenty of emerging players out there, but it feels like Google, in particular, will continue to be deeply important for at least the short- and medium-term future. We’re certainly looking at all of the what-if scenarios to [determine] how we manage through that, or change what we do, or advocate for the experiences we want to see on Google.”

Another executive from a global outlet that has held talks with AI companies without striking any deals said one thing that would “have to be baked into any [licensing] deal” was an opportunity to “participate in the forward-facing development of news products” so as to “protect … against showing up in ways that would seem to be reputationally damaging and/or damaging to user trust.” While this CEO was “relatively optimistic about certain tech partners and their interest in actually collaborating and wanting to develop products that work for users and work for partners,” they added that the dynamic is different when it comes to smaller companies that are primarily staffed by engineers, rather than by lawyers and partnerships managers.

At times, the kind of access and sway described by these interviewees has been framed as a perk of formal partnerships, such as the ones OpenAI has established with some publishers, which typically offer cash and API credits in return for access to publishers’ archives. For example, The Atlantic’s senior VP of communications, Anna Bross, told Damon Beres, a senior editor on the magazine’s technology team, “The partnership gives us a direct line and escalation process to OpenAI to communicate and address issues around hallucinations or inaccuracies.”

Describing the key components of the OpenAI deal, The Atlantic’s CEO, Nicholas Thompson, told the Verge, “[T]here is a line back and forth. So when we see something, like in browse mode we notice something interesting about the URLs and the way they’re linking out to media websites. You go back and forth and those things get fixed. So our sense is that we are helping the product evolve in a way that is good for serious journalism and good for The Atlantic.” In its rollout of ChatGPT Search, OpenAI stated that it “collaborated extensively with the news industry and carefully listened to feedback from our global publisher partners.”

Such access is, of course, beneficial to the likes of The Atlantic, although Tow Center research has found that even partners are not spared from inaccurate or “hallucinated” summaries or citations. Given that these issues also affect outlets that don’t have formal deals, questions remain about the access and responsiveness that will be afforded to news organizations outside the platforms’ privileged inner circle of “premium” partners.

Brand dilution

Interviewees also raised concerns about the scope for third-party news summarization products to dilute their brands — a concern that can be traced all the way back to our earliest report. “The biggest challenge is that all the research shows that when we become disintermediated, people don’t give the credit for that journalism or the value that they’re getting from the service to [news organization] — they give it to Google, or they give it to YouTube,” an executive news editor from a major international outlet said. “They think, ‘Oh, this is this great thing I’ve watched on YouTube.’ None of that credit goes to [news organization] and then you’re back to your business model. If you need to compel people to pay [for your journalism] because they believe you’re valuable enough to part with that money, then you are that one step removed, and again you’re degrading how you’re presenting yourself to people through that generative experience.”

Another news executive at an international outlet raised a similar concern in the context of content licensing agreements, saying, “When you license, you’re effectively giving the AI company the ability to disaggregate everything that you do, at the most microscopic level. Your brand, to a very large extent, disappears. … I can understand the short-term financial gain. But I do worry where all this leads.”

Highlighting another way in which the challenges of today — and tomorrow — drew comparisons to earlier episodes in the platform-publisher relationship, one executive said that many of the central questions around generative search would be familiar to those who have weighed the pros and cons of the Apple News ecosystem. One such question, the executive said, was: “If we’re putting our content into this ecosystem and it’s being remixed in these ways, when does it show up? How does it show up? How do we grow that audience? Basically it’s a new kind of generative SEO: How do we best connect our content to the needs of this new ecosystem so that we can serve our audience there better?”

Direct relationships only grow in importance — today and into the future

During discussions about how to prepare for a reconfigured, more disintermediated information ecosystem — one of the most recurrent themes to emerge from any aspect of our research — was that it is more important than ever for publishers to cultivate direct relationships with their audiences. This echoes a growing trend in our 2019 report, and came up in a range of contexts:

- Interviewees from outlets with strong, direct connections to their audience feel most insulated from any drop-offs in search traffic caused by generative products;

- Concurrently, generative search poses an existential threat to outlets without a strong, loyal audience;

- As we edge toward a generative search future, those direct relationships are more important and valuable than ever;

- While some interviewees said their organizations are agreeing to partner on third-party generative AI products because they want to ensure they’re reaching their audience via as many avenues as possible, others said their organizations are declining to partner if they consider them too big a threat to direct relationships with their audiences.

Once the traffic era’s vast — albeit relatively brief — influx of eyeballs had subsided, many news organizations vowed to retrain their focus on their most loyal audiences. If that was publishers doubling down on direct relationships, then our interviews suggest that some are now seeking to triple down on that strategy as the unknowns of generative search loom. That is because, if done well, generative search has the potential to give news audiences less reason to leave the third-party search environment. With that on the horizon, “You have got to accelerate everything that you are doing that is about your direct relationship with the consumer,” one executive editor at a major international outlet put it.

They continued: “We have been moving at a huge pace into signed-in users and weekly active audience being the North Star metric, because we know that you’ve got to have that route to your audience, as that is where you can re-engage and directly communicate with them, or else you’re at the mercy of a third party.”

For news organizations that can resist the short-term lure of a large check from an AI company, concerns about trading away hard-earned connections to loyal audiences are a vital factor when weighing the relative merits of entering formal partnerships or licensing deals. An executive from a large legacy outlet that has rejected the overtures of various AI companies said, “Clearly, too, what we would think good looks like [in a deal] is being able to maintain direct relationships with users. We’re not interested, at the moment at least, in becoming pure suppliers to a platform to no additional end. We are still very much in the direct relationship business.”

Uncertainty Around the Revised Value Exchange

Interviewees outlined numerous reasons for publishers to be wary of third-party generative search products:

- They are a disintermediating force that expands the distance between publishers and audiences.

- They carry threats to brand integrity and visibility over which publishers have minimal control.

- In addition to sapping traffic, they are likely to reduce the flow of audience to publishers’ owned-and-operated platforms, harming opportunities to cultivate relationships and encourage news habits; generate revenue via ads; and drive conversions of subscriptions, donations, and product sign-ups.

- Unless otherwise stated, they are being trained and improved by journalism produced by the news organizations whose audiences they are expected to cannibalize.1 While not mentioned by any of our interviewees, safety concerns and governance issues have arguably hampered OpenAI’s effort to foster the image of a reliable partner.

This raises the question: What’s in it for publishers? The topic of “value” recurred in a wide range of interconnected contexts, including:

- AI companies’ perceived failure to articulate their value proposition to news organizations, creating uncertainty over the revised value exchange;

- The absence of any value exchange when AI companies trained their LLMs on news content without notice, permission, or compensation;

- A misalignment of views between platforms and publishers over the civic and economic value of journalism;

- A misalignment of views between platforms and publishers over the value of platform traffic to news organizations.

Given the degree to which generative search platforms and products like Perplexity, ChatGPT search, and Google AI Overviews have reduced the flow of traffic to news outlets’ owned-and-operated platforms, interviewees noted that the current value exchange (crudely: traffic and/or audience in exchange for access), which has underpinned a significant proportion of the platform-publisher relationship to date, is not at all clear-cut when it comes to generative AI.

“There’s definitely a change in the value exchange,” said one CEO at a global outlet. “This idea that we would give access to our content and in exchange we would get audiences, obviously that’s now disrupted.”

Another interviewee said, “There’s some really fundamental questions about how the open internet has worked up until now and what that compact is between platforms and people who create high-quality IP.” Honing in on the value proposition part of the puzzle, they added, “If the compact was traffic, well, that no longer exists — or is likely to diminish significantly in a context where they summarize your content and munge it with many others and hold the user. The objective is clearly to hold the user within that interface, so [audiences] don’t need to go off to a third-party site in order to consume news or anything else.”

In the words of a former platform executive: “So my concern is: What is the publisher getting in this space?” This executive encouraged news organizations to block AI companies’ crawlers unless the (currently unknown) perks of access aligned with publishers’ long-term strategy and goals. “From a news publisher’s perspective, you are trying to achieve a lasting and sustainable relationship with end users. So you need to work out how and if your relationship with the AI companies will get you towards that goal.”

A policy expert at an international newspaper noted that the AI companies’ “argument falls apart in terms of how the internet economy has worked for 20 years. First, they have to come forward to explain to publishers why they should opt in to allow their content to be scraped to build these models, and as part of that, what is the value exchange they are willing to give to publishers in order to get access to the archive and to live journalism as it’s published? And that’s completely lacking at the moment from all of the major incumbents.”

That interviewee was one of a few who described negotiations over a revised value exchange as a two-step process. The first step, in this view, involves retrospective compensation for news content that has already been scraped and used to train LLMs without consent. “There’s a sense that we have copyrighted material that we invested considerable amounts of money in that has been taken and used and exploited. And there has been no value exchange. So how do you recover the very real value of what has been taken with nothing in return from a whole set of technology and AI businesses?” said one CEO at a global outlet. Another interviewee referred to this step as “fixing the leaky bucket.”

The second step centers on the establishment of suitable compensation if publishers are to provide the grounding and real-time data AI companies will need to produce timely, accurate, verified responses to queries that cannot be answered using their foundational models.

An AI leader from a global news organization summarized the major areas of contention as “a big difference of opinion in terms of what is allowable or not under copyright under different jurisdictions; a very different philosophical view about what ought to have been scraped or not and the basis on which it’s been done; and very different views from the platform operators about whether they are willing to pay a toll or admit the need for an ongoing value exchange.”

Our interviews suggest that any negotiations over a revised value exchange can be expected to rekindle longstanding tensions caused by misaligned views about journalism’s economic and civic value and how that value should be recognized.

Interviewees from the platform side offered particularly strong insights in this regard, often citing philosophical differences over the value of journalism as one of the issues at the core of the uneasy relationship between the two parties. “It’s very much not understanding each other’s position and acknowledging what is important to each other,” one former platform executive said.

An interviewee from another platform said, “Tech companies value news on revenue created for them in their businesses, which is de minimis, if not zero. News companies value it on societal impact, almost in a qualitative way and not a quantitative way. And therefore they are just not even talking about the same metrics.”

A third described how this disparity had tangible implications for their day-to-day work, as they had to be mindful of the stark contrast between how the value of journalism was conceptualized internally and externally. “It is true that news queries don’t monetize,” they said. “So the fact is, the internal conversation was always that the numbers make it fairly clear that the monetary value is de minimis, and it’s always going to be. But there’s no good way to hold that conversation externally.” Consequently, this person said, the value discussion had to be radically reframed for external audiences: “When talking to publishers and partners, it was always mission-based: News is important, [platform] users come looking for information, news is a very important class of information, and it’s fundamental to our mission to try and surface that type of response to a query. Nothing, though, which implied a certain value. Nothing like, ‘So therefore, news results represent X amount of value to [platform] or to any other platform.’ That was, of course, a conversation we always avoided, [partly] because we couldn’t really quantify it.”

Given the dominant internal view that journalism’s financial value was relatively negligible, this third interviewee concluded, “The value piece was always more mission-driven. Certainly, for those of us who’d been there a long time in the publisher partnerships world, it was always just a losing battle because no matter how much we said it mattered to [platform] — and it did — there was no check that was ever going to be big enough to solve the fundamental point of tension on all of this.”

By contrast, an interviewee who spent a number of years in a senior role at another platform before it made a sharp pivot away from news described their former colleagues’ attitude toward news — particularly those in engineering — as “something that fills a box in our product. And if these boxes are used more often than the others, then it’s useful content, and if not, then it’s not [useful], and we don’t care.’” They continued, “There is no mission. The only ones who cared about journalism and news at [platform] were the team that was dedicated to news, and to a certain extent, to be fair, a couple of people on the executive board who felt that this was important. But the general attitude is: It’s content.”

Interviewees with platform experience typically sympathized with the view that AI companies’ current value proposition, such as it is, seems heavily weighted against publishers. However, almost all suggested that too many news organizations had downplayed and/or ignored the extent to which they derived value from platforms during the traffic era, and/or made unrealistic claims about what was “owed” to them.

“The piece of this value equation that no one ever talks about is the value to publishers,” said one former platform executive. “The reason everyone has SEO departments and was doing all this kind of stuff is because that traffic has value.” The head of an AI startup whose previous work at the intersection of journalism and technology included a spell at a tech platform said that while they’ve “always been focused on the economics … the notion that if you link to something, you should be paying them in addition to the traffic you’re sending has made no logical sense in the context of the web. It felt very much like extortion.” This statement epitomizes the gulf between platforms and publishers in terms of how they value journalism. From the perspective of many publishers, of course, the platform-dominated online environment is what’s extortionary, since whatever value they might derive from fickle bursts of traffic doesn’t come close to covering the ongoing costs of a robust newsgathering operation.

A former executive of a different platform said this area required improvement as pressure mounts to find a solution to AI’s parasitic relationship to news. “There has to be an open discussion about compensation. What was always left out in the discussions about the unfair balance between the publishers and the platforms was the value that publishers get from being on the platforms. Because when we discussed all these deals in [different countries] and where we had [paid platform product] coming up, there was always this, ‘Oh, you owe us money. And our content has so much worth to you because you make so much from advertising, blah, blah, blah.’ They were never interested in actually revealing how much revenue they were making on the traffic that came from the platforms.”

Another former platform executive recalled an “extraordinary moment” during one negotiation when representatives of a news chain revealed the figure they believed was owed to them by the interviewee’s platform. This figure, the interviewee said, not only “showed how completely far apart we were,” but that the parties were “just on different planets.”2 Efforts to place a dollar figure on the lost revenue “owed” to publishers by platforms have generated much discussion, as well as methodological critiques. NiemanLab said one figure was “based on math reasoning that would be embarrassing from a bright middle schooler,” while Semafor’s Ben Smith concluded a later attempt was an “extremely aggressive, as well as pretty rough, and Swiss, estimate — but also a transparently-presented entry in a high-stakes argument.”

To avoid similar hostilities, discussions over licensing for LLMs “need to be approached in a more sensible way on both sides,” according to the first former platform executive. “What I see is almost big tech companies gaslighting publishers into believing precedents have been set, deals have been done, and benchmarks are there. … It doesn’t have to be that way,” they said. “Collaboration [between publishers] is the leverage point, but they need to do it in a sustainable way and not have unbelievable, ridiculous, grandiose views on this.”

Elsewhere, we did hear cautious optimism that technology companies’ perceived inability to view value through any prism other than their bottom lines may be a factor in improving relations. While acknowledging a raft of caveats, one of the former platform executives said, “I’m partly optimistic platforms and publishers can get back together, and hopefully in a better way than we did in the past, as there’s now a different need for the content that publishers have to offer. … And it actually has a distinguishable value to the future business model of AI.”

Traffic

As noted earlier in the chapter, a key change to tech companies’ value proposition is the expectation, now largely fulfilled, that advances in generative AI will further diminish the flow of traffic from platforms to sites owned and operated by news outlets. Accordingly, interviewees often framed their level of concern about the knock-on effects of generative search through the prism of their outlet’s current reliance on search traffic.

At one end of the scale, an executive at a digitally native outlet said, “If our Google referrals were to decline significantly tomorrow, it would cost us something like five or six percent of our overall revenue. It would be infuriating, and let me tell you, I don’t want to have to find another five percent from somewhere else. But it’s an existential threat for a lot of other places, and it’s not an existential threat to us.”

By contrast, an executive at a legacy outlet said, “This is a major crisis, right? We have seen search referrals drop year over year. We’re seeing referrals from all sources falling. And so it is the real challenge of trying to figure out how do we actually find and engage audiences?”

At times, interviewees cited broad metrics as an indication of what they stood to lose. A digital editor at an international outlet said, “I’m worried about what it’ll do to our traffic because, quite seriously, we can get about 50 percent of our traffic from search.” Describing a similar reliance on search traffic, an editor from an international local news chain said, “In about 2018, somewhere in the region of 60 to 70 percent of traffic to our sites was internal traffic. Now that’s shifted to about 20 percent, and about 55 percent of traffic for [local title] is coming from Google. So Google is absolutely huge to us as a business. In other [local titles in the chain], Google traffic can go up to about 60 or 70 percent.”

This interviewee said their chain’s dependence on Google traffic was a source of consternation and a warning sign about the rise of generative search. “By shifting all of our direct traffic to them through news aggregators [Google News, Chrome Suggestions] and Discover, Google were very, very clever,” they said. “It’s the whole thing with the frog, and turning up the water by one degree, and then the frog doesn’t realize it’s being boiled. They were very, very good at implementing that news aggregator technology and taking out the direct traffic. And people see it as a good thing: Google traffic was going up. I think they’ve misstepped on generative. They’ve gone too far too quickly. And I think it’s awoken a lot of people to actually how bad this is going to be in the long run. We’re the providers of information and we want to be the distributors. But Google now wants to be the distributor.”

While the hit to traditional search traffic is a concern for many, disrupting Google’s stranglehold on the search market could break a cycle of dependence stretching back decades. “Something like 25 to 30 percent of our traffic comes from search,” an executive at an international, subscription-based outlet said. “That is a huge dependency on a supplier on any level. There’s no other part of our business that hinges on one supplier in quite the same way. Yet there is absolutely no contractual relationship that underpins that whatsoever. If you think about it, that’s quite mad, right? If someone said, ‘I’ll be your paper supplier, I’ll supply 30 percent of your paper or 30 percent of your workforce, but we don’t have a contract, we’ll just kind of do it on a handshake that didn’t even really happen,’ you’d say, ‘Of course not. That’s insane. Why would I do that?’ So I think once bitten, heavily, on behalf of the publishing community, we’re all thinking we’re not going to get bitten twice.”

While Google was front-of-mind for most interviewees in this context, an executive news editor from an international outlet noted that, while their team had done a range of tests to model the potential implications of generative search swallowing a large portion of their traffic, they were “already dealing with really different types of search experiences,” as search “more generally is radically changing” because “we know that the vast majority of people under a certain age will turn to Instagram and TikTok and search there before they will use Google.” Indeed, an April 2024 survey by Forbes Advisor and Talker Research of 2,000 Americans found that 45 percent of Gen Z and 35 percent of millennials are more likely to use “social searching” on TikTok and Instagram over Google.

An executive from a global subscription-based outlet agreed that while nobody could precisely predict the downstream impact on search traffic, their five-year plan included modeling declines ranging from 5 to 30 percent. The benefit of this “war-gaming,” as they termed it, was that it allowed them to plan ahead for the downstream impact on their outlet’s audience, revenue, and discovery: “OK, well, if it’s 30 [percent decline], what will we need to have done on our end to ensure that we’re a destination site, to drive subscription repeats, to drive more engagement on the site? What are we going to do about that?”

Google Zero is the term coined by The Verge’s Nilay Patel for the “moment when Google Search simply stops sending traffic outside of its search engine to third-party websites.” Interviewing Meredith Kopit Levien, CEO of The New York Times, in 2023, Patel said, “I’ve lived through Yahoo going away; I’ve lived through Facebook going away; I’ve lived through a very strange moment of Snapchat going away. I feel like we would be making a mistake if we didn’t envision what it would look like if Google went away.” During our interviews we heard examples of something tantamount to Google Zero being preached internally, so widespread was the belief that generative search platforms would throttle that particular audience tap. An audience executive described how senior leadership at their outlet had been “pretty clear in basically saying search is going to zero for news organizations.” The message from the top of their organization, they said, was, “social is going to zero. SEO is going to zero. Don’t rely on any of that.”

In the short term, this creates a disparity between senior leaders who are “so far in the future” and today’s “practical reality [which] is that [news organization] is incredibly buoyed by search at the moment.” As of summer 2024, “search traffic continues to go up and it’s an increasingly big part of our traffic,” they said.

A positive effect of this approach is that it both eliminates the need to war-game potential traffic-loss scenarios and insulates the outlet from the stress of waiting for the severity to come into focus. As this interviewee said, “We might see a drop in search traffic, but because of what [senior leadership] is saying, it really doesn’t matter at the end of the day. We’re not banking a future for search in any capacity. We’re counting on it being zero. So anything that is above zero is really gravy.”

On the flip side, with audience management and SEO very much part of the mix for many today, this focus on a rapidly different tomorrow can create internal management issues. “I literally run these things. You can’t go around telling people they’re going to zero. I have to work with people and tell them that it’s not going to zero [yet] and that they should care about [traffic] today,” the audience executive said.

This strategy of treating search traffic as a nice-to-have rather than a need-to-have resonated with other interviewees, many of whom had dealt with the aftermath of traffic taps abruptly drying up during the social era. Musing on the idea of adopting a Google Zero mindset, an executive from a global outlet said, “In some senses, it’s a kind of back to basics. It’s an unhooking from an ecosystem which has proven to be a fairly fickle friend.”

Another thoughtful perspective on a Google Zero-esque scenario came from a nonprofit news executive who had previously held senior roles at for-profit outlets:

In every role that I’ve had this century, there was always a tension where, if we were looking to engage audiences on, say, Facebook, we’re figuring out how we drive people from there back to [the website] where we have ads on pages and can make money, or where we drive subscriptions and can make money. I’m in an organization now where that’s not a thing. It’s a nonprofit news organization, so impact is the goal, not budget. There’s a freedom to that because it’s possible that as long as we’re able to track that impact, it’s possible that a partnership where there’s no traffic being driven back to [our website] could be fine. I would want to be really cautious about what the impact of feeding [news organization’s] content into an LLM could have on the organization, but on the other hand if there is the potential for wide impact, then a thing that would be a drawback in my old life but not in this current one — no driving of traffic — might not be a bad trade-off.