Executive Summary

A number of factors contribute to the development of information security cultures in the newsroom, including investment in information security specialists who liaise with journalists about their specific needs and provide both informal and formal security training. Or news organizations may hire individuals in traditional roles, such as part of the IT department, but who also have information security knowledge. Journalists also bring information security knowledge into the newsroom out of curiosity, and the belief that information security practices are important for them to get stories and do their jobs. These security champions—who become trainers by accident—work to support colleagues and convince them of the need to adopt more secure practices, through informal conversations, brown-bag lunches, and training sessions at the individual, desk, and newsroom level.

Despite these developments, information security cultures in many newsrooms are nascent for reasons including ongoing financial crises and labor precarity in journalism, both of which can limit the allocation of resources for information security. Moreover, journalists dislike taking security steps that might slow down their reporting in jobs that are already precarious, and awareness of the myriad security risks to journalists and news organizations is limited. All of these problems may be compounded by a lack of institutional buy-in and provision of resources to deal with these risks; often, silos between different parts of a news organization impede information sharing about security internally and externally to the newsroom; and institutional memory related to security may suffer when a trainer leaves. Newsrooms are organizations which, depending on size, financial state, ethos, and management structure, may suffer from both bureaucratic inertia and traditional power structures that limit change. But smaller organizations with less bureaucracy tend to have fewer resources to implement security related practices and policies. There appears to be more awareness of security practices in locations where news organizations are highly concentrated, such as the Acela corridor, rather than in more geographically distant locations elsewhere across the country.

Some journalists are “security champions” within their news organization, but between security considerations and journalistic craft, tensions may emerge: visibility, verification, usability, and speed. For example, journalists may try to protect themselves from online harassment by limiting communication channels such as direct messages (DMs) on Twitter, yet by doing so, they also reduce the number of ways that potential sources can communicate with them. In the last two years, more news organizations have adopted the anonymous whistleblowing platform SecureDrop, but because of its anonymous nature, it can be challenging for journalists to verify the information received with it. Additionally, secure technologies like PGP encryption for email are challenging for many journalists and sources to use, which limits the adoption of the tool by both parties. Secure communications may also slow down publication, and speed is a currency that journalists and editors prize and prioritize. Journalists may prioritize a source’s comfort with regard to communication, so if sources do not push for encrypted communications then journalists won’t necessarily do so either. Among some journalists there is a resistance to the notion of protecting a source because it belies a so-called bias and lack of objectivity. However, in some cases, such as in the investigative realm, journalists are motivated to learn information security technologies to protect their sources, while for others, taking steps to improve information security operates as a signaling mechanism to future sources to say that they can be trusted with the source’s story. Sometimes it is less about source protection and more about concerns that the credibility of the news organization may be at risk if internal communications about a story are leaked or subpoenaed.

Security, although networked in nature, is not always viewed as a collective issue or one requiring a collective response. Depending on their role in the news organization and their knowledge about information security, journalists and management may not believe certain secure practices are necessary or applicable to them. Additionally, some journalists have a “security by obscurity” mental model which limits their willingness to implement information security technologies because they believe that, since they are not working on anything “sensitive,” they have little to no risk of digital attacks. Older, more established journalists may not see why certain new technologies are necessary to journalistic and editorial workflows. The dynamic and yet precarious nature of journalism also encourages journalists to use their personal accounts and devices and various wi-fi connections as they travel and research a story, despite heightened insecurity.

Further, journalists may not take the time to threat model or develop and follow a risk assessment. They may not be up to date because of how quickly secure technologies change and how frequently vulnerabilities arise. Such varying information can result in a form of security nihilism, in which journalists give up trying to use security technologies because of the caveats and complexities of such practices. Depending on the resources available to them, they might not have individuals to reach out to for expertise on the tools and practices, and may stick with known practices and habits. Shared norms around which platforms to use (e.g. Slack) can contribute to increased vulnerabilities if they are used without understanding the ways in which information is transmitted or stored.

Journalists may be hesitant to share their practices or knowledge about information security because they may have a sense of bravado or competition, or are concerned that doing so may make them more vulnerable to security risks. The power dynamics between editors and journalists, and journalists and sources, may encourage less secure practices in order to obtain a story and get it out quickly. Responses to perceived or real restrictions on journalists’ autonomy may result in resistance, reluctance or circumvention of security practices. Security practices also tend to be reactive, following a concerning incident, rather than proactive, which can limit their effectiveness.

Security concerns overlap with other dimensions of journalistic practice including legal concerns related to information protection and subpoena requests. Information security practices necessarily engage with existing networks and infrastructures that have insecurities and vulnerabilities, while new vulnerabilities can be introduced when the integration of systems and tools is necessary but not supported. Sometimes security trainers and IT staff try to forefront security without understanding the particular needs of journalists and their workflow, which in turn can result in journalists circumventing restrictions in order to pursue and publish their story.

A number of elements are necessary to facilitate the development of information security cultures in newsrooms. These include:

- Increased literacy around information management and security throughout the newsroom; policies and practices at the organizational and individual level, beginning with onboarding of new staff in the organization

- A shift in perceptions of what information security practices can provide to journalism (including empowerment of sources) and an understanding of how they are needed

- Ongoing training sessions to encourage sustained behavior change; development of secure and usable technologies to facilitate widespread adoption from sources to journalists

- Buy-in and a cultural expectation that security is important from the management and editorial level

- An understanding that developing an information security culture is ongoing, iterative, and proactive, and needs to be integrated into existing journalistic norms and workflows

Introduction

Journalists have long considered the United States a country that upholds the right to report critically and independently. Yet, an increase in government-led leak investigations, online harassment and physical attacks against members of the media has begun to puncture what was a robust environment for freedom of the press in the United States. Contributing to this deteriorating environment is the current US President, Donald J. Trump, whose constant attacks on the press have aimed to delegitimize the media and their role in holding power to account. Trump has called the media the “Enemy of the People” and has leveled false accusations against them near-daily in an effort to persuade citizens to disbelieve negative media reports about him.1 Such an environment reduces trust in the media among members of the public and increases cynicism and passivity.

The current administration’s demonization of the media has also contributed to an uptick in online and offline harassment and physical violence against its members. The president’s rhetoric stirs up rage at his trademark rallies, where he encourages his supporters to hassle and assault reporters.2 Some of his supporters have sent death threats; some have plotted to murder members of the media.3 Although press freedom organizations have long tracked physical violence, imprisonment and assault among journalists around the globe, it has only been in recent years that press freedom groups have turned their attention to the United States.4 Since its establishment in 2017, the US Press Freedom Tracker has documented more than 400 incidents involving press freedom violations.5 Physical attacks include journalists who face violence and injury or equipment damage in the course of their work or from a targeted attack. Reporters have been attacked at Trump rallies, assaulted during live broadcasts, punched in the face and called purveyors of “fake news,” and harassed and manhandled when covering protests—to name but a few instances. The physical attacks and online harassment are taking their toll on journalists, resulting in mental health crises and burnout.6

Additionally, there has been intensifying online harassment against journalists in the US and abroad. According to a 2019 survey by the Committee to Protect Journalists, online harassment was identified as the biggest safety issue for journalists.7 Indeed, 90% of respondents in the US (out of 115 surveyed) believed it was the biggest threat. Eighty-five percent of respondents agreed that journalists have become less safe in the last five years. More than 70% said they had experienced safety issues and threats with the majority related to verbal harassment followed by online harassment. Female journalists are more likely to experience digital sex-based discrimination than their male peers8 and minority journalists and those who cover hot-button issues like white nationalism or race are often targeted.9

Journalists also have experienced a wide range of threats from phishing (messages containing malicious links) and distributed denial of service attacks (which take a website offline) to software and hardware exploits of a user’s devices, among other hacking attempts.10 In 2014, Google experts discovered that 21 of the world’s 25 most popular media outlets were targets of state-sponsored hacking attempts.11 In 2013, the Chinese government hacked The New York Times, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal12, and the Syrian Electronic Army hacked the Associated Press, resulting in a tweet that briefly sent stocks into a nosedive.13 More recently, the Times’s Moscow Bureau was targeted by Russian hackers.14

Another concern facing journalists is the increasing ubiquity and interconnection of digital technologies, which can generate data and metadata about ourselves, our networks, our locations, and our habits. Of course, there are numerous positive aspects of digital technologies for journalists; but they also track and collect data, which can compromise key tenets of journalistic practice such as communicating with sources. Journalists, as collectors, curators and disseminators of information, are at heightened risk for potential observation and investigation by powerful entities they hope to hold to account. The Snowden revelations clarified our understanding of the nature of some surveillance programs that can implicate journalists and journalism, and we need only look to the news to see other examples of journalists being surveilled, their communications accessed, or their sources investigated.

Although thinking about information security technologies may be particularly relevant for our current administration, there were also intensifying efforts to investigate the sources of leaks during the Obama Administration. Indeed, the Obama Administration’s Justice Department prosecuted more than twice as many leakers under the Espionage Act than in all previous administrations combined. In 2013, law enforcement secretly obtained the records for more than 20 telephone lines associated with AP journalists, including their home phones and cell phones, ostensibly to identify the source or sources behind a specific story.15 Meanwhile the FBI sought and obtained a warrant to seize all of former Fox News reporter James Rosen’s potential communications with his source, including his personal email, phone records and his security badge records to identify his movements to and from the State Department.16 17

Surveillance has gained new power and relevance in the last several decades as the creation and deployment of new technologies expanded the capacity to surveil and be surveilled. Surveillance—in its myriad forms—is intricately intertwined into our daily practices and experiences living in a digitally connected society. Journalists, as collectors, curators and disseminators of information, are uniquely positioned to be at risk from routine and automated monitoring, as well as from sophisticated and targeted surveillance by powerful corporations and states.

Thus, journalists and their sources are unable to know how or to what extent they may be monitored, or how this information may be used against them.18 Metadata trails can identify journalists and their sources without the threat of a subpoena, while the development of identification and surveillance software from facial recognition technologies at public venues to license plate scanning and CCTVs can exacerbate the problem.19

The use of spyware against journalists is increasing in many countries around the world as states strive to control information and as technologies to surveil civilians become more sophisticated and inexpensive. This confluence of factors is creating a new reality for journalists globally as they seek to express their ideas online. The creation, sale, and deployment of surveillance technologies such as spyware suites have been increasing over the past several years, as indicated by leaked documents from the Wikileaks Spy Files, Citizen Lab investigations, NGO reports, and news articles. Recent headlines have shown sophisticated surveillance technologies being used to surveil Ethiopian, Bahraini, and United Arab Emirates activists, Saudi dissidents, Mexican and South American journalists and lawyers among others.20 In January 2020, it was also revealed that NYT journalist Ben Hubbard was targeted by NSO spyware in June 2018.21 The creation and selling of sophisticated surveillance systems by companies in western democracies to authoritarian regimes further facilitate this asymmetrical power dynamic between states and their citizens.

Adding to journalism’s long list of challenges is the ongoing financial hardship and labor precarity facing most forms of media. Local news has been hit especially hard in the United States, with vast news deserts sweeping across the States, contributing to ill-informed publics and severed communities. Meanwhile, nearly everyone from local and national print media to digital-first publications like BuzzFeed and Vice are laying off journalists in droves, reducing the ability of news organizations to take the pulse of current events, engage in investigative journalism, or inform the public and hold power to account. Nearly 8000 journalists lost their jobs in 2019, the highest level of attrition since the recession in 2009.22 In response, news organizations are increasingly turning to syndicated content from wire services and other publications to fill in the holes in their local and city papers, while aggregator sites like Google News and Business Insider amass readers. Media companies are still struggling to find a successful business model for digital news, since digital advertising revenue sells for a fraction of the cost of ads in print publications in the past.

Despite these myriad and interconnected challenges, news organizations are only beginning to develop information security cultures in the newsroom. In this report, I examine how security cultures are being established and maintained in leading news organizations in the United States and the various challenges they face. I clarify how information security practices among journalists and in newsrooms more generally may be changing journalistic cultures and norms of professionalism at a time of increased labor precarity and loss of trust in the media. In doing so, I connect the empirical study of journalists’ changing digital news practices and newsroom culture to the larger question of what is and what journalism can be in an age of surveillance. Studying this issue matters because journalists are rhetorically instrumentalized as an essential component of a liberal democracy in their roles to inform the public and to be a check on powerful interests by reporting on corruption and malfeasance.

Method

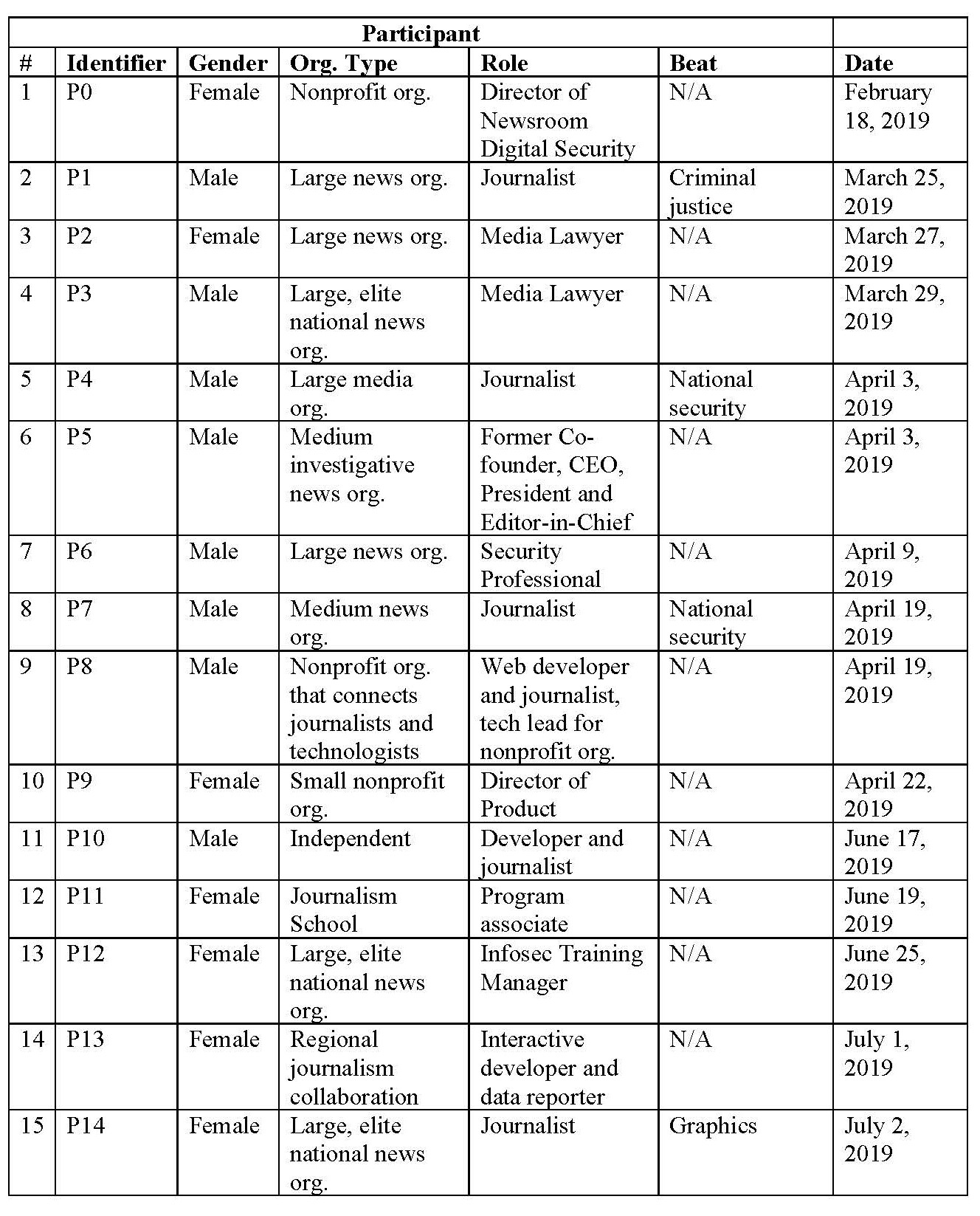

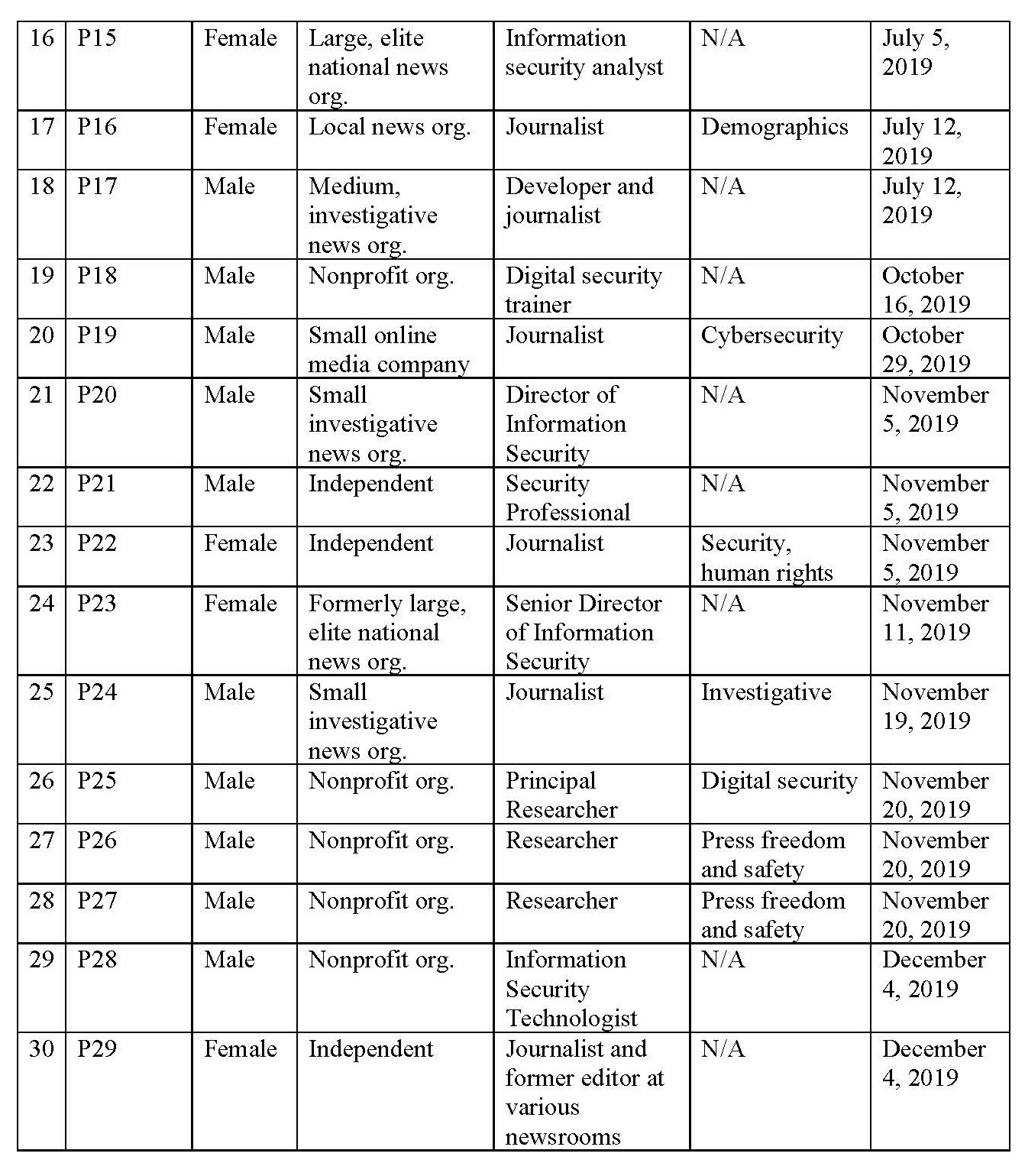

Between February and December 2019, I conducted 30 semi-structured interviews with journalists, information security technologists, and media lawyers from national and local news organizations in the United States, and individuals from nonprofit organizations and academic institutions. I selected the subjects via a snowball sample (in which I began with a small population of known individuals and then expanded the sample by asking my interviewees for suggestions of others to interview) because of the sensitivity of the topics discussed. Interviewees represented a wide variety of organizations in terms of sizes and cultures, including small, medium and large organizations and mainstream, local, digital first and investigative outlets. The aim was to obtain a diverse sample that reflected a range of perspectives and practices among journalists and adjacent actors in the newsroom. I also interviewed individuals associated with nonprofit news organizations and academic institutions, including OpenNews, Freedom of the Press Foundation and the New School because of the interviewees’ experiences with information security or systems thinking at the organizational level. (See Appendix I for interviewee information.) The interviews were conducted in person, via phone or voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP). The interviews lasted an average of 46 minutes, and the interviews were recorded and transcribed.23 I utilized Charmaz’s (2006) constructivist grounded theory approach and open coding techniques on my collected data.24 I also used a constant comparative method in which categories develop through an ongoing process of comparing units of data with each other.25

Caveats and Limitations

This report is written with an underlying assumption that journalism, in its capacity to inform and to hold power to account, is important for a democratic society and that communications between journalists, sources and editors are necessary for fulsome reporting on issues of import. This report relied on a purposive snowball sampling method because conversations about information security practices among journalists and newsrooms require trust. Therefore, it provides a snapshot of the different types of security cultures in newsrooms, which is not quantifiably generalizable, but has implications for other newsrooms in the United States. Additionally, this report will not identify any individual who has asked to remain anonymous.

Discussion and Findings

This section will examine three main components of the report. The first section will evaluate specific flashpoints that have raised security awareness among journalists. The second part will interrogate how security cultures are being developed in newsrooms and the third section will describe the different countervailing tensions limiting the development of security cultures.

Flashpoints Raising Security Awareness

Critical incidents raise awareness of information security for a time and can act as a motivator. Journalists indicated that current events and news stories related to the Snowden revelations, the DNC hack and Trump’s election and ongoing data breaches are all contributing to a sense of information insecurity and awareness of a deteriorating environment. Additionally, certain incidents are hitting even closer to home and affecting journalists and/or their colleagues in personal and professional ways. Journalists acknowledged the intensification of doxing and online harassment, source exposure and legal threats, digital attacks from DDoS to hacking as reasons behind why they are starting to be more concerned about the information landscape and the vulnerabilities it poses to journalists and their ability to carry out their work. Additionally, journalists and information security technologists pointed to social and cultural shifts that are disabusing journalists of the notion that they are in a protected and venerable professional class.

The Snowden revelations and the Snowden story

The Edward Snowden revelations that began in 2013 ushered in a new understanding for many journalists about the capabilities of states and corporations to conduct widespread mass surveillance. News organizations who were able to report on the revelations with first-hand documents took immediate, extensive measures to try to ensure the classified documents they were writing about and the stories which resulted from them were secured before they were published and that they were able to report on the stories without being preemptively stopped. These measures varied in terms of technological sophistication and more analog measures.

The revelations of surveillance also spurred discussions among the journalistic community and the information security community about how to keep one’s communications private from prying eyes. Suddenly, there was significant interest among many in understanding how to encrypt communications in transit and how to encrypt your data at rest. Numerous digital security workshops sprung up and crypto parties were offered in cities around the world, seemingly at a greater pace and breadth than pre-Snowden. Said one national security journalist:

It took Snowden to make me really see in provable documented ways just how extensive the surveillance dragnets are. I had thought that I was utilizing secure measures of communications before and then it turned out…no. Really, this thing is hard to evade and you have to be extremely careful considering not just the technological capabilities of the dragnets, but the legal authorities that they claim in order to operate them and the application of them against citizens. (Interview, P7, April 19, 2019)

Another reporter said that he quickly became interested in information security technologies after he joined The Guardian toward the end of the Snowden investigation because he knew that Snowden had required the recipients of information to install PGP, among other measures, but also because he saw his new colleagues at The Guardian “being very, very careful” and following protocols to protect the information. “Obviously that story was such a huge success that it really drove home to me how important that sort of thing was going to be for these kinds of stories from then on.” (Interview, P1, March 25, 2019, p. 2)

A data journalist who didn’t work on the story nonetheless agreed and said how journalists were communicating with Snowden to get that story “was eye-opening to a lot of journalists.” (Interview, P10, June 17, 2019, p. 12) A media lawyer said, “I think Snowden was a shot in the arm about awareness” both in terms of “what his documents showed, and also how the reporters went about doing that story.” (Interview, P3, March 29, 2019, p. 5) Another journalist and digital security trainer said that all the workshops he did about information security at NICAR were jam-packed following the Snowden revelations and that “people still demand that topic at that conference.” (Interview, P17, July 12, 2019, p. 1)

The Snowden story has been helpful in teaching journalists about information security. Said one security expert, “people are really drawn to the sexy stuff…when I’m giving trainings and we get into…all right, well, Edward Snowden just contacted you. Like what do you do next? Like people want to talk about that and people don’t want to talk about why I think you shouldn’t have your family on LinkedIn.” (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019, p. 7)

DNC hacks and Trump’s election

While the Snowden revelations opened up journalists’ eyes to surveillance and ways to encrypt information, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) hacks brought home how easy and how devastating it is to be hacked. According to a national security reporter, interest in information security among media professionals “definitely peaked again” following the DNC hacks. He said he thought this was:

…partly because we all saw how relatively straightforward the hack was to start with, the phishing emails that were sent to people like Podesta…we’ve all seen emails like that in our inboxes…and just the huge damage and impact that could result from a…thoughtless click on one of these phishing emails… if these sorts of hackers want to target political groups, they probably are going to want to target media as well and they’re going to want to try and discredit media who are reporting on them, and that we and other media organizations could definitely be a potential target for similar things. (Interview, P1, March 25, 2019, p. 3)

According to a data journalist, the DNC hack was a wakeup call for journalists because even though it was simple, it was sophisticated. “It’s no longer the guy from Nigeria asking you for $5 million. That’s not what they’re doing anymore. It’s much more sophisticated than that.” (Interview, P10, June 17, 2019, p.11) Another journalist said that the DNC hacks should provide motivation to newsrooms to implement information security practices:

Have them recall what Russia did with the emails that they hacked from the DNC and then later from John Podesta. What they did was to weaken them institutionally—they published the most embarrassing, the most cringe worthy, and the most internally divisive things they could. Unless you make this [information security] your priority, it’s a matter of time before that happens to you. (Interview, P7, April 19, 2019)

Concerns about information security among journalists were also heightened leading up to and following the election of US President Donald Trump. A security professional for a digital-first company at the time said he “might’ve surfed on a wave of paranoia post-Trump.” He continued:

In fact one of the big discussions that we had in our newsroom was to emphasize before we understood what was going to happen with the election, the idea that both administrations would be threats to press freedom in different ways—that we would have to have different struggles. But I think ultimately when Trump won, it was such an emotional response. (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019)

A media lawyer for an elite news organization said he saw an increase in the volume of threats that journalists faced during the 2016 US Presidential Campaign:

…There would be isolated incidents before that where a story would cause great displeasure and you could expect this onslaught. But I think starting with the campaign, we started seeing more of it, then after the election we certainly saw it as well, you know. But I would say 2016 with the beginning of what I thought of was a real ramp-up. (Interview, P3, March 29, 2019, p. 2)

These concerns manifested in more journalists and sources willing to download and use the encrypted messaging service Signal. A national security journalist said he saw an increase in the expectation that Signal would be used for communications from people he didn’t know or expect would be interested in using it and that this expectation surged in November 2016. “I definitely remember a spike in using it after Trump’s election and I mean immediately after…” (Interview, P7, April 19, 2019)

According to another journalist who became the de-facto information security trainer in her newsroom:

…the 2016 election was really a big wake-up call for a lot of people…we already had some folks who were using ProtonMail. We started pushing folks pretty heavily toward Signal. And then…after the new year, after the election, was when we really did, like a big sweep. We taught everyone how to use Signal and taught everyone how to use ProtonMail. And then the following year, in 2017, we implemented SecureDrop and did another round of security training…the election really galvanized a lot of journalists. (Interview, P29, December 4, 2019, p.1)

An information security director for an investigative outlet agreed. He said that the election of Trump was a flashpoint for many journalists. “I think that when Trump got elected…everyone was like, ‘Oh, fascism is almost here.’” (Interview, P20, November 5, 2019, p. 26) The worsening environment for journalists has resulted in journalists becoming more interested, but not necessarily eager to learn more about information security to protect oneself. An information security technologist said he saw an increase in journalists’ interest in security because they were getting “snapped out of” their day-to-day by a president “who is attacking the press on the television, on Twitter, every single day.” This “felt extremely jarring. It felt shocking, it felt unusual to reporters. And suddenly they’re paying attention. And security is something that people feel that they have some control over…” (Interview, P25, November 20, 2019, p. 9)

Ongoing breaches

The increase in the number and scale of data breaches and scandals in recent years have also raised journalists’ consciousness to the risks and repercussions of insecure practices by companies, agencies and individuals. Said one cybersecurity reporter, the 2014 Sony hack26 in particular was a “big catalyst” and “showed everyone that it could happen to anyone.” (Interview, P19, October 29, 2019, p. 9) He continued, “I mean we’re literally talking about a company that makes movies…no disrespect, but it’s not the NSA, it’s not the DNC. And they got all of their emails plastered on Wikileaks…it was a great case study for saying, ‘Hey guys, this could literally be us next week. We need to take this seriously.’” (Interview, P19, October 29, 2019, p. 9)

Another shocking moment was the Cambridge Analytica scandal. “Since then we have been asking some more pointed questions in the media, but also as citizens, just about the nature of these tech companies. Like what kind of access do they have? Should they have that access? Under what circumstances should they have access to our personal data?…I see people asking themselves about alternatives more than ever” said an information security technologist. (Interview, P25, November 20, 2019, p. 11)

To others, it’s been the ongoing nature of such breaches that have increased journalists’ consciousness. Said another national security reporter, “The steady drumbeat of slightly scary infosec stories has just made people much more aware in general that their data is probably fragile and slightly precarious and that people shouldn’t automatically assume it’s secure.” (Interview, P1, March 25, 2019, p. 4)

Intensifying harassment and doxing

Additionally, there have been intensifying online harassment and doxing campaigns against journalists.27 According to a media lawyer at an elite news organization:

“Domestically, there has been over the last two or three years, an increasing number of online threats, email threats, phone threats, usually targeting reporters who have for whatever reason made somebody unhappy, usually because of coverage of the Trump administration. Sometimes it’s other topics, but it tends to be reflective of the partisan divide in the country today. And sometimes not directly Trump. It can be about perceptions of political correctness, about writing articles sympathetic about immigration or any of the other topics that tend to be hot-button ones.” (Interview, P3, March 29, 2019 p. 1)

Journalists across a range of beats receive threats but female and minority journalists tend to be targeted more intensely and frequently. Additionally, journalists who cover local or national politics or extremism receive more sustained and severe abuse.28 A journalist at a local media organization said her managers started to care more about doxing29 once the news organization diversified its staff a little bit. She said:

“When I joined it was whiter than it is now. And this isn’t a problem that white people face as much as brown and black people do…you hire a bunch of people and they start complaining about it so you’re suddenly hearing more” about it. (Interview, P16, July 12, 2019)

She soon found that whenever she did a story, regardless of whether it had to do with race or diversity, she would receive harassing emails. “When I finally told [my editor] that we needed to do something about it was when I was doing stories that had nothing to do with any controversial topic really. But people would still find a way to connect it with something.” (Interview, P16, July 12, 2019)

Contributing to the likelihood of online harassment and doxing is the availability of one’s personal information online. “I had a hacker buddy who…used some search service and found my parent’s names, a property they had owned, you know, in like two minutes. And it’s like it’s creepy. You know? That’s what I would like to avoid.” (Interview, P4, April 3, 2019, p. 6)

A cybersecurity reporter said that doxing was “the most likely scenario for most journalists…because it’s easy to do and all it takes is angering a source or somebody connected to the source. And the damage can be very high, especially in terms of stress, remediation in terms of like, maybe you have to worry about how you go home, what bus you take, what public venues you attend.” (Interview, P19, October 29, 2019) He added that it has been “underestimated for a long time…because it seemed like it was something that gamers did against each other…maybe journalists thought they were off limits, that no one would dox them…Maybe we got cocky or we got over confident that no one cared about our lives. But we now know that that’s not the case…and it seems like some journalist gets doxed or threatened to get doxed…almost every week….” (Interview, P19, October 29, 2019)

This reporter said that part of the reason that doxing appears to be intensifying is because it is “literally kids play” and it’s challenging to know how to successfully counter it:

“…there’s no app that saves you from doxing. It’s something that you have to sort of worry about all the time and defend against all the time. And the only way to do that is by having someone that keeps up with how doxing works and what to do to prevent doxing. And also again, you need to train journalists…I guess, worry less about the NSA or Russia hacking your email and worry more about random people on the internet publishing your home address on Twitter.” (Interview, P19, October 29, 2019)

Anyone can dox a reporter, and some journalists expressed concern that they could be a target of online harassment or doxing from upset sources. Said one reporter, “I’ve certainly pissed off sources and not necessarily even sources…but people in that world who I’ve been uncomfortable having pissed off.” So far, he said, “I’ve been pranked, but not hacked.” (Interview, P4, April 3, 2019)

Journalists have more awareness and concern about doxing because they’ve reported on it or know someone personally who has experienced it. (Interview, P16, July 12, 2019) An information security trainer agreed and said that the journalists she’s worked with have been more proactive about security in response to concerns about being harassed or doxed, especially if they’ve heard stories from colleagues about what has happened to them. She said, “I’d say it’s definitely a main concern journalists have, but most of the people I’ve talked to haven’t actually been doxed. I think they just see the potential of it happening…and they’re scared and they want to take the preventive steps to reducing this information…There is a smaller set of people that have been targeted that way who have been very vocal of, ‘This happened to me and this is the impact it had,’ and that’s been enough to encourage other people to start looking at ways to reduce it.” (Interview, P12, June 25, 2019, p. 14) She argued that it is important to be proactive rather than reactive when trying to minimize the potential for online harassment and doxing because “when it’s in a reactive situation, there’s not a whole lot you can do.” (Interview, P12, June 25, 2019, p. 18)

DDoS, hacking and source exposure

Other times, journalists and news organizations begin to care more about information security when they are directly targeted by distributed denial of service attacks (DDoS) or nation-state hacking attempts. Said one journalist and news apps developer:

A couple years ago…We pissed somebody off on the internet and our email system was hit by a denial-of-service and nobody’s email worked. At that point, I think, at least at [our news organization] everybody started learning about secure alternative ways of communicating. People started to realize that we are vulnerable to threats like anybody else. (Interview, P17, July 12, 2019, p. 2)

There have been non-targeted attacks against news organizations in the form of ransomware, but also targeted attacks by individuals and nation states who want to intimidate news organizations and find out information. According to one information security technologist, nation states and powerful individuals don’t want to be written about so they hire people to dig into who is writing stories about them, and learn who they are and what their motivations are in order to compromise them in different ways and to discredit them. (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 10) Another information security technologist concurred. He said that nation state actors “like to have a leg up when it comes to understanding whether or not you’re reporting on them, and if so, how? What do you know? Who are you talking to?” (Interview, P25, November 20, 2019, p. 8) “It’s rare that you’ll have a hacktivist…who’s going to hack a news organization because they feel a certain way about a story or something. That’s not what we normally see.” (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 10)

Cases in which sources have been exposed, arrested or charged with espionage, have also resulted in raised awareness and concern among journalists about the need to learn and successfully implement information security technologies. One security technologist said that his organization had sources who were charged with espionage, which was definitely a “flag” and a concern for journalists in the organization. (Interview, P20, November 5, 2019, p. 25) Another cybersecurity reporter said, “We don’t want to do that. We don’t want to be the next guy that exposes a source, who gets the source arrested.” (Interview, P19, October 29, 2019)

Another data journalist said, “All the other sources who’ve gotten burned by poor operational security I think may have had the effect of…Wow…they had all the things, and it still didn’t work. It’s even harder than some people were pitching it to be.” (Interview, P10, June 17, 2019, p. 12)

Meanwhile, media lawyers described that when the government launches a leak investigation, “They don’t need to come to [the outlets being investigated]. They run into a variety of complications when they come to us and there’s the optics of it and everything else. I think that they would prefer not to and if they don’t need to, they don’t.” (Interview, P3, March 29, 2019, p. 4) Instead the investigations are more centered on looking at government employee’s own electronic footprints. Another media lawyer agreed, “They don’t bother subpoenaing us anymore, and I think that’s because of information security reasons. They can just go get the data elsewhere. They can subpoena it from third party providers. They can capture it using technological methods if reporters don’t protect themselves.” (Interview, P2, March 27, 2019, p. 2-3)

Cultural shifts

These challenges are occurring amidst cultural shifts facing the news media. The public has a lack of literacy about the media’s role, which is complicated by tensions of a 24/7 news cycle in which reporters operate as pundits and confuse facts and opinion. Some have argued that the rise of the always-on news cycle has led to more commentary, opinion, and speculation which has resulted in less distance between factual information and other forms of information. (Interview, P8, April 19, 2019, p. 12)

There is also a perception that the news media is more partisan than it has been in the recent past, which has led some members of the public to treat it less seriously or accurately. According to a former CEO of an investigative news outlet, “[Y]ou have the president of the United States referring to the top of the journalism pyramid, The New York Times, as ‘the fake news failing New York Times.’ There are people that regard what they see there, if they see it at all, or if someone tells them about it, to be suspect.” (Interview, P5, April 3, 2019, p. 1)

Not only do segments of society view all media as partisan, but some view journalism as the enemy.

[T]he thing that is so screwy about the universe that we live in, apparently, is that there actually are a bunch of people who do mess with journalists just for kicks. And they hang out on 4Chan and Reddit and whatever and decide to mess with people. But then there’s also this parallel universe of people who…want to tear down journalism because they make money off of having bitter partisan divides be the way that we operate in the world now. So there are a lot of different folks with motivating factors out there who love to see real journalists fall down. (Interview, P8, April 19, 2019, p. 11)

An information security technologist who has worked with journalists for years concurred and said that there are “actors who want to see the media destroyed…Some of them are centralized actors, some of them are decentralized actors.” He argued that it was essential that news organizations understand that “some communications are not about the free exchange of ideas, but rather they’re part of an attack against the media and they need to be seen as that. So when I talk about harassment of reporters, that’s an example where for a lot of organizations, they’re slow to realize the nature of what I think we call today—bad faith attacks.” He said it’s important that the media see these types of communications for what they are and not treat them like good faith exchanges of ideas that warrant responses. (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019) He said some organizations were better at this than others. “…Without naming names…some organizations are quicker to understand this. I think ultimately local news actually struggles with this because it’s unclear sometimes when you wade in. I mean, that’s part of the challenge of these things. It’s unclear to a lot of reporters when they wade into a thing that they don’t realize is a thing.” (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019, p. 4)

According to an information security technologist and former journalist, news organizations need to understand that they have a duty of care to protect their newsroom. Journalists are facing doxing and online abuse and other attacks and “the duty appears on the organization as far as I’m concerned to protect these folks,” the technologist said. “Someone posted your address because they don’t like what you said about Trump. Like that’s real, right? And we’re in a new day and age and you can’t have no digital defenses. It’s not just about, like, encrypting a message that some source gave you. There’s other elements to this.” (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 9)

These elements include helping ensure journalists are prepared to combat online harassment and doxing as well as other challenges. According to another information security technologist, news organizations are “rather comfortable” with legal challenges in which a “very powerful organization threatens to sue and the news organization says ‘bring it on.’” Yet, they tend to “wither” when it’s an attack from “social media mobs” who use shaming tactics to call for the firing of an individual or something similar. He said that the media “throws in the towel immediately in the face of that, where it seems to stand up very strongly to authoritarian governments or legal threats.” (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019, p. 2) He added, that:

“Ultimately people need to feel safe doing this kind of work. So we want to make sure… to create a resilient newsroom…where people feel empowered to go and do adversarial reporting because they know that where they sit in their desk is safe and they know that their management will have their back.” (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019)

This is especially needed in an environment in which the public response to journalism and journalists is more violent and immediate than it was in the past. “In today’s day and age, people feel like they can like, ‘oh I didn’t like that story. I’m not going to argue about the stats behind it or the quotes. I’m just going to go after you as a human being.’ Right? The gloves are off. That’s how the public feels.” (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 9)

Developing Security Cultures in the Newsroom

News organizations are developing security cultures through a variety of mechanisms and practices including adopting SecureDrop, providing tip pages with various ways to communicate with journalists, building in-house information security teams, and having internal sessions dedicated to information security topics through brown-bag lunch meetings and peer-to-peer learning of information security tools. More than 65 major news organization globally, including news organizations in the United States such as The New York Times, the Washington Post, ProPublica, and The Intercept use SecureDrop.30 SecureDrop is an open source whistleblower submission system that news organizations can install to anonymously and more safely receive tips from sources. For five years, nonprofit news organization The Freedom of the Press Foundation has led the development of SecureDrop and helped news organizations install it. A significant number of news organizations publicly launched SecureDrop in 2017. A number of news organizations adopted or reinstated SecureDrop in 2019 including NBC News, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, The Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, The Dallas Morning News, Slate, Süddeutsche Zeitung, ProPublica, Business Insider and others.

Although many news organizations have had tip pages on their website for years, some announced new tip pages with the announcement of their SecureDrop installations. These tips pages generally include ways to leak to the news organization via various means including encrypted applications like Signal and WhatsApp, SecureDrop, postal mail, among other methods. Freedom of the Press recently reviewed the websites of more than 80 top online news outlets31 and found that email and postal mail are the main ways investigative reporting sites solicit news tips, but Signal and SecureDrop are nearly as common. (Figure 1)

In-house information security teams

Although many news organizations have had dedicated, in-house expertise related to physical security for some time, some news organizations are developing roles for information security in their newsroom. According to publicly available LinkedIn data, news organizations range from having no one dedicated to information security on staff to having many roles in the newsroom with information security in their job description. News organizations differ in size and resources, with The New York Times a leader in both. Therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that, out of eight news organizations examined, it had the highest number of individuals with “information security” as part of their official title.32

The rise of the “security champion”

The majority of news organizations do not have a dedicated team for information security. As such, information security lives in different places within the news organization and is often not standardized within or across news organizations. One journalist and former information security trainer said that “it ends up in a lot of weird places” from data teams to investigative, national security, politics and even a special project innovations lab. “It varies depending on medium, it varies depending on corporate ownership structure.” (Interview, P29, December 4, 2019, p. 8)

Another journalist and digital security trainer said that awareness of security in a newsroom spreads as a result of “proximity to people who are already concerned,” whether it is because a reporter got doxed, or the news organization’s website was taken offline because of a DDoS attack. These incidents spur internal discussion, which in turn spreads awareness of the different types of steps people can take to mitigate such concerns and threats. (Interview, P17, July 12, 2019, p. 8)

Cross-pollination of security knowledge occurs across the newsroom with journalists from different desks swapping information and knowledge. According to one digital security trainer, such sharing of expertise has occurred throughout their newsroom with the international team helping the investigations team to learn how to do bigger international stories, and the investigations team acting like the digital security experts to the rest of the company, while the desk covering the alt-right were the ones who best understood the harassment piece. (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019, p. 11)

A few digital security trainers pointed to the importance of the investigative teams for spurring discussions about information security. One trainer said this was because the investigative journalists “know people that have had stuff happen to them” and “they’re kind of curious that way.” (Interview, P18, October 16, 2019, p. 6) Another journalist recounted how the investigative team in his news organization helped to ensure others knew the basics of information security and also offered to be a resource for more specific questions and follow-up. Another trainer said that “…investigations is going to be more interested in information security than style”, which “is an area we’re still trying to navigate and find a good way to work more closely with these teams to help them understand the need…” (Interview, P12, June 25, 2019, p. 7)

Other times, a news organization has hired people who have a lot of knowledge about information security, but it’s not necessarily part of their job description to implement anything specific related to it. Instead, when security knowledge transfer happens, it’s “sort of happenstance.” (Interview, P2, March 27, 2019, p. 11) Indeed, journalists who may be more technical, like data journalists, are sometimes counted on to help out the newsroom in various ways, including by answering security questions from other reporters. A developer and journalist said that his hometown paper doesn’t have anybody in the newsroom who’s a security expert “but they do have people who do technical work…And so having been in that role, in that newsroom, I know what type of tech support questions you get. And sometimes it’s because the printer doesn’t work. But other times it’s because they’re working on a story and they want to be able to figure out how to do a particular type of analysis. And in other cases it’s a security question.” (Interview, P8, April 19, 2019, p. 4)

Still other times, journalists who are more technically inclined get pulled into a bridge role within their news organization because resources are scarce and technical abilities differ. This type of role is more common among journalists with technological skills than those in non-technical roles in part because certain projects they are involved with need “communication and collaborations across different teams within the newsroom and also across different departments within an organization.” (Interview, P8, April 19, 2019) There is “just tons and tons of peer-to-peer training, whether it’s somebody at the desk next to you, like, ‘Yeah, I can show you how to do a pivot table. That’s what you need for this story that you’re working on.’ Or, like, ‘I can do a brown bag lunch that explains how to install Signal on your phone.’” (Interview, P8, April 19, 2019, p. 7)

According to a data journalist:

I think at the root of anything that I’ve been able to change at [my news organization] so far, it’s just because I’ve cared about it…Anything that I’ve done, I’ve just gone ahead and done it, and then asked for sign-off. Asked for forgiveness, not permission, kind of thing. Generally, my managers have been very welcoming to any ideas I’ve had as far as changes to the team. It’s not that they didn’t think it was important. It’s that they didn’t think of it, or they didn’t have time to think of it. I guess it’s just finding sneaky ways to integrate things like that. (Interview, P14, July 2, 2019, p. 10)

The reliance on data journalists as the information security experts is problematic, because they are not necessarily the same thing. As an information security technologist put it:

I remember when I was at The Times as a data journalist, I was…harassing my editor…to get on a phone with people at Freedom of the Press to talk about SecureDrop…What I’d hear in response was that they didn’t understand why doing so was important…IT and data journalists are not information security experts. But in your average news org they’re the closest thing. That’s what people believe. But it’s not the right shape to go through that hole. It’s not correct mapping at all. But, you know, it’s like the best they have right now. (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 16)

Anyone in the newsroom can be a so-called “security champion” or “security advocate” if they are sensitive to the notion that information security is important for journalistic practice. One media lawyer said she has found security champions across her organization. She said,

Interestingly, they’re not all necessarily national security reporters. One of them was a science reporter. There was another one who was a guy who did visual work. They know a lot about the subject matter, and they know a lot about the technology, and they just happen to be really into it and they encourage people to use it in a certain way. They are, in some ways, some of the best ambassadors. They get it. They know how to do it, and they can explain it to their peers. (Interview, P2, March 27, 2019, p. 12)

Other times, a lawyer in a media organization may believe that information security is important for journalists to learn and use in their work. A media lawyer said,

My interest in information security is really more of an intellectual one than a practical one. I don’t want to use any of these tools themselves, but I do understand conceptually why they’re really, really important…I’ve done some training for the reporters. I’m like, ‘Here’s basically what the risks look like and what some of your options are.’ I can’t make anybody do anything. I can just provide information. I think it helps that they feel like, ‘Well, there’s a lawyer who says this is something that’s valuable and so we will take that seriously.’ Then it’s up to them to look into it. (Interview, P2, March 27, 2019, p. 12)

Information security trainers’ leveraging of “security champions”

One way digital security trainers are trying to level up security in the newsroom is by having one-to-one conversations with certain journalists—so-called “security advocates”—to get them onboard with the notion that security is important and then have them advocate for improved security practices to the rest of their team. “We need to find a couple people to buy into what we’re doing on that specific desk before we can make real progress with that team when they don’t already have that culture of security-mindedness on their team.” (Interview, P12, June 25, 2019, P. 7)

Doing so helps to “foster the culture to create a community that is passionate about and interested in and supportive of the work that you’re doing” said Runa Sandvik. When she joined the Times in 2016, she was part of the larger security team, “but there was no one that was dedicated to the newsroom. And in the newsroom, some people knew that there was a team, but couldn’t name anyone on it. Some people had no idea there was a security team at all. There were people that didn’t get what I was there to do. Didn’t understand my role.” She said that through finding “security champions” or “people across the newsroom that understand the role, understand the work, are interested in security” she was able to understand what they needed, share information, and help them drive best practice across their desks, teams or projects.” This point of entry allowed for other discussions and training sessions to occur, whether in the form of a brown bag lunch, sitting in on someone’s weekly meeting, or teaming up with different departments, like legal, to talk about risks related to travel. (Interview, P23, November 11, 2019, p. 7)

Another digital security trainer said that security champions are behind the development of security cultures in several places because they eventually start talking to their bosses and their peers and get people started thinking about security, but “their mileage varies based on, like, how receptive management is.” (Interview, P18, October 16, 2019, p. 6)

The IT Department can also shape the culture of security within a newsroom

Sometimes technology staff who are in charge of securing journalists’ devices or device provisioning become impromptu security champions, said a digital security trainer. In the course of their work they realize that they could take security a bit further and facilitate working securely in a more systematic way. (Interview, P18, October 16, 2019, p.6) In other cases, it’s “a software developer that’s, like, really into [the] Snowden stuff, basically. And it’s just like, ‘Hey, we should get SecureDrop, that would be really useful. We should be protecting our sources and stuff.’”(Interview, P18, October 16, 2019, p.6)

The digital security trainer said that it is not necessarily an entire department that would advocate for working more securely, but rather one or two people who are “just really into the idea” and “read a lot on the subject” and “have a certain amount of knowledge on it…And are like, ‘Hey, we should do this too.’” (Interview, P18, October 16, 2019, p. 6)

Another journalist said that “at [his news organization], we’ve finally started expanding our IT side, so we have a new IT Director who is very on top of…it’s like security is front of mind for him. I mean, he’s been great to work with.” (Interview, P17, July 12, 2019, p. 1) Another security technologist said newsroom IT workers tend to know more about security than in the past. (Interview, P29, December 4, 2019, p. 16) A security consultant for a large news organization concurred and said that “some of the best security champions come from our IT team and our infrastructure site reliability engineers.” He added that, in his experience, this was the same for organizations like the Washington Post and Vox. (Interview, P6, April 9, 2019, p. 11)

Sometimes IT contributes to a more robust security culture, not by being an overt and visible security champion, but by keeping technologies in-house and relying less on third-party platforms, which might comply with subpoenas. According to one media lawyer: “[Our organization] does a couple unique things to begin with. We don’t use a lot of third party servers. Everything is an internal proprietary system. Part of that is because of the way our distribution network works. We needed to have our own system. There’s a certain amount of security that’s built into that…and I think there is a perception that it’s adequate. I don’t think the journalists feel like, for the most part, they need to do more than that.” (Interview, P2, March 27, 2019, p. 11)

Journalists lean into their own networks for security knowledge

Other times, support for learning information security practices arises within a subcommunity, like the cybersecurity beat. According to one cybersecurity reporter, “I do think that [cyber]security journalists are relatively supportive of each other…because it’s a hard subject to cover and…many of us end up meeting in the same handful of major conferences and frankly we talk to a lot of the same sources, that for whatever reason, it is a relatively nice camaraderie.” (Interview, P4, April 3, 2019, p. 4) He also added that there has “been a dramatic shift in how security practitioners and security experts address people who are not experts and that includes journalists.” He’s noticed that there has been “Way less condescension. Way less gatekeeping…I think they’re more patient, kinder, have better rapport [with] journalists in general.” (Interview, P4, April 3, 2019, p. 4) This better rapport and communication can help to improve journalists’ knowledge of security and the implementation of information security tools and practices among readers. In turn, the cybersecurity reporter can spread knowledge about security internally in terms of what practices and devices journalists can use, but she may also serve as a translator for the rest of the newsroom when wide-scale hacking stories and data breaches occur. “Like the gist of the DNC hack wasn’t that complicated but some of the specifics, it would be easy to get lost in the weeds and you need to have…somebody on staff who can parse that quickly for the rest of the newsroom,” said the cybersecurity reporter. “And so it’s kind of a one, two strike of this person both has a [cybersecurity] beat, but also can be the larger translator for the rest of the newsroom.” (Interview, P4, April 3, 2019, P. 5)

Another information security technologist described how journalists go within their own networks to understand security concerns and questions. “It’s very insular. People go within their journalistic confines—their dim sums or coffees or whatever they do—and they share and trade information there. Sometimes at conferences, but usually it’s pretty siloed, based on trust.” (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 2) A security analyst also noted how journalists often rely on their own networks, including their one or two security people. She talked about how she wanted to encourage journalists to draw on the resources of her news organization’s information security team and also “empower people to take security into their own hands” by showing them how to investigate and evaluate risks on their own. (Interview, P15, July 5, 2019, p. 15)

Sometimes the publication of a piece that explains how journalists used secure technologies to get the story can teach journalists reading or watching the piece to take similar precautions. (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 2) Additionally, journalists tend to become more concerned, aware, and interested about information security issues when they read about them in the news or hear about them from their peers. In response, information security teams pivot to what’s top of mind. Said one information security analyst, “A big thing that I like to focus on is travel security and what goes into that process…news cycles have brought this up really recently.” (Interview, P15, July 5, 2019, p. 7)

Journalists also learn about information security from virtual peer networks like the News Nerdery Slack, which also has a security channel for individuals who work as journalists or have other roles in the newsroom to discuss questions and concerns. According to one interviewee, the News Nerdery Slack is a “consistent and ongoing space” for security conversations while other lists have “fizzled,” but she also pointed to the need for newsrooms to utilize their own networks to better support security cultures. (Interview P9, April 22, 2019, p. 8)

Various efforts to encourage the diffusion of information security technologies and practices in newsrooms have involved outside groups who have utilized a peer-to-peer learning framework. In 2017, OpenNews and BuzzFeed’s Open Lab created “The Field Guide to Security Training in the Newsroom,” a modular curriculum for security trainers and “accidental experts” who are responding in non-formalized ways to requests from peers and others in the newsroom about digital security and privacy questions.33 The guide was a result of a community effort that was kickstarted in the summer of 2017 when a dozen journalists and experienced security trainers convened at Northwestern’s Knight Lab to create the first draft of the guide, which was then subsequently tested and refined in the following months.

The goal of the guide was to provide a teaching resource to newsroom workers without the money to bring in outside experts. According to one of the leads on the project, “…we felt like the specific newsroom need was for support for people who kind of accidentally end up as trainers because they don’t have necessarily a security background themselves, but they’re the nerdiest person in the newsroom;” someone who fools around with technology all the time and is the person that folks go to for help. (Interview, P8, April 19, 2019, p. 2) The guide provides lesson plans that allow journalists to teach their peers about security tools and practices. “We wanted to hit that specific newsroom need of, like, ‘We’re a small newsroom. We do regional coverage. We don’t have a security expert on staff. How can we kind of level up our people and do some peer training?’” (Interview, P8, April 19, 2019, p. 2-3) He said “a big point and goal of writing the guide was to identify and support a handful of meaningful steps that newsrooms could take to improve digital security.”(Interview, P8, April 19, 2019) Each of the lesson plans represents a single concrete thing that an individual can do to incrementally improve security. (Interview, P9, April 22, 2019, p. 7)

Amanda Hickman, who helped lead the development of the guide, gathered feedback from individuals who used the guide to train others in their newsrooms. Participants in the sessions had a significant level of interest in understanding the specifics of technologies and how these technologies worked together. Many of the questions were about how something works or why something happens, as well as what Google has access to and whether Facebook is listening to one’s audio. She said the questions reminded her of ones someone might have of a nutritionist, because they were very general questions that probably everyone wants the answer to. “For me, that kind of reflected the fact that I think there’s a lot of frustration and confusion in general…people have a lot of questions about privacy and security and they don’t feel confident about where to get reliable answers…People need safe places to ask stupid questions and they need that about everything. I think security is a place where a lot of people feel dumb and they feel like they are supposed to know and they don’t want to acknowledge that they don’t know…” (Interview, P9, April 22, 2019, p. 4-9)

Interviewees differed as to whether newsrooms need a specific position dedicated to teaching journalists about information security, or whether a more sustainable change would arise from reporters becoming more knowledgeable about information security and training others. According to Hickman, “…I think there’s room for there to be somebody whose paid responsibility it is to be aware of risk and threats and concerns and take responsibility for keeping the rest of the newsroom up to date…” (Interview, P9, April 22, 2019, p. 8) Some information security trainers are wary of this approach because of the ease with which a news organization could let a position and the person go. (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 17)

There has also been movement from proprietary thinking around information security to more collaboration, with the rise of technologists in the newsroom, and technologists acting as intermediaries. According to one technologist, “…there was a hesitance to even share tools in the beginning or like processes that people use internally… ‘this is how our newsroom collects these things, or how we handle that stuff.’ There was an idea that needs to be a secret…but I think as more technologists get involved in news gathering, they share the idea that security through obscurity isn’t a thing.” (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 13) Despite this supposed opening-up of security practices, he acknowledged that journalists are competitive and protective of their methods and sources because of the work that they’ve put into them. “…there’s an element of ‘I earned this,’ you know?…maybe I don’t want to tell you everything that’s going on here because these are my sources.” (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019, p. 13)

Toward a “culture of encouragement to be secured”

According to a journalist who worked on the Snowden story, an awareness and respect for security pervades his news organization even as it treats security needs for a story on a bespoke basis. He said, “…it’s case by case and it’s beat by beat really. But we’re definitely a culture of encouragement to be secured, let’s not use open email with sources that need confidentiality and let’s always be aware of that stuff.” (Interview, P1, March 25, 2019, p. 4)

Similarly, at The Intercept, journalists are largely comfortable with implementing information security practices and technologies. This is partly due to “a culture where people realize that security is important.” (Interview, P20, November 5, 2019, p. 2). “People seem to be fine with that [information security]…I think once there’s organizational support for doing all of this stuff, then it’s actually not that bad. Even using PGP, which is awful. But it’s not that bad if somebody else sets it up on your computer.” (Interview, P20, November 5, 2019, p. 7)

Additionally, at other news organizations, a climate of security has started from the top. According to one journalist, “Our editor-in-chief came from Wired, he’s been covering national security for 20 years. Like, he totally gets that world…spies and secure comms and all of that. So…it really came from him saying, you know, ‘I think this is not just going to be affecting national security reporters. I think it’s going to be affecting all of the political reporters and nearly all of the journalists in our umbrella.’ So we started small by…piloting with a few people, but…ultimately rolled it out to the whole newsroom.” (Interview, P29, December 4, 2019, p. 1)

Another journalist agreed that top leadership was essential for security to be infused throughout a newsroom. He said, “It’s got to be from the top down, it’s got to be leadership. It can be suggested and brought on by reporter-level people who take this seriously and are experts. I think that’s a good thing, but they need to be making their pitches as high as they can, because inevitably the way the capitalist structure of a newsroom works is management can force things in a way that the average reporter in the investigative unit cannot.” (Interview, P10, June 17, 2019, p. 11)

Another local journalist agreed, and described how, in her organization, security awareness started with her managing editor replacing their morning meeting on Wednesdays with training sessions that covered a variety of new tools and techniques, including security sessions, that were peer-led. (Interview, P13, June 25, 2019, p. 5)

Some interviewees suggested that the more technologically inclined and young a news organization is, the more nimble and savvier they might be about security. According to a cybersecurity reporter, “BuzzFeed has a great security culture. They have a security team that is a whole-of-company team. It’s basically two guys. Very involved in the newsroom, very forward-thinking, very creative. There’s whole kits for when someone’s gonna be traveling abroad, especially to a country…where evil maids might be a threat. Probably goes overboard, but it’s one of those ‘better safe than sorry’ things.” (Interview, P4, April 3, 2019, p. 3)

Others have described how smaller newsrooms that were “basically born of paranoia and of thinking about mass surveillance” like The Intercept have a “digital security training mindset” and an “operational security mindset that’s just ingrained into the way they do everything” although “not always perfectly.” (Interview, P18, October 16, 2019) Others described how The Intercept’s “governance structure” facilitates security even on a small budget. An information security technologist said, “…they’ve shown that you can be small and not have a big budget and be scrappy as long as you have a security team…[and the] team has power to slow things down and force people to do things and work on stories. And you can get stories you can’t normally get.” (Interview, P28, December 4, 2019)

A media lawyer for an elite news organization said he thinks security implementation is “scaled appropriately to what reporters are doing. I think our reporters who were engaged in national security work are much more attuned to the need to use Signal or WhatsApp or meet in person…I think that risk prevention should be scaled to the reasonable risk perceived. And if you’re covering the New York City school system, you probably don’t need to think about those things in the same way that if you’re covering the NSA. I think most reporters who are doing anything that sensitive, you know, it needs a higher level of confidentiality, are much more aware of the digital tools available. So you see people saying, you know, ‘Can I call you on Signal? Can I call you on WhatsApp?’ where before they would just call.” (Interview, P3, March 29, 2019, p. 5)

Even in newsrooms that have security awareness at the top level, cross-collaboration related to security issues is needed to provide a more holistic response. “At The Times, there’s the information security team, there’s a corporate security team, there’s an international physical security team, there’s legal. You have a separate networking team, and you also have a separate team that is the IT Help Desk and the team issuing your laptop…and there’s some engineers in the newsroom, as well,” said Sandvik (Interview, P23, November 11, 2019). To address the intersecting challenges that arise, The Times uses working groups with various stakeholders for a more thorough and comprehensive evaluation of a threat from all angles (Interview, P15, July 5, 2019, p. 10). The coordination depends on the issue at hand and can involve the information security team and legal.

It’s also important for reporters to get to know the information security team so they can reach out to them when they have a question and so that the security team can better understand the unique pressures and challenges facing journalists and how to best integrate security practices into journalists’ existing workflows. The development of these relationships helps to build trust. Said Sandvik, “…it is one thing to share your potential story with general counsel of the company and a bit different to share it with the security person who joined a month ago…It takes time to get to know people and build that level of trust just for them to know the different things that you can help with…” (Interview, P23, November 11, 2019, p. 10)

It is also important to assess the different needs of a news organization, whether it’s the business side or editorial and adjust training materials accordingly. “For the newsroom, this has shifted to more, ‘How do I protect my social media accounts, and what do I do when I’m getting threats and harassment online? How can I reduce that footprint online and how can I securely communicate with my sources?’” (Interview, P12, June 25, 2019, p. 1) She said it’s not just recommending a certain technology or app to use, but articulating the reasons behind the recommendation so journalists can dynamically pivot to a different tool that works better for their sources.

Security needs to fit the needs and culture of the newsroom while also addressing the business side of the news organization.

I think for journalists, it’s more personal when you’re talking about security, whereas [on] the business side, we’re talking about maybe how to protect the company’s data, and how do you securely manage it and make sure that only people that need access are accessing it, and with the newsroom, I feel like it’s more important because there is this gray line between your personal life and your professional life…I think the need for it is higher, for the newsroom, just because it crosses more over in a personal life, but actually getting them to sit down and dedicate the time to devote to that is where the challenge lies. I think part of that is … you really have to be clear, to communicate the value of what you’re trying to do with that person in order to get their time and dedication to that thing.” (Interview, P12, June 25, 2019, p. 2)

In smaller investigative outlets, a newsroom might form a team of reporters, their editor, a security person, and a lawyer to talk through a threat model and help figure out what it is safe to talk to the source about, and how it might be safe to reach out to other people and give them certain information about the story. (Interview, P20, November 5, 2019, p. 18) Such collaborations are often decided on a case-by-case basis in his newsroom and aim to integrate security into the journalist’s workflow and provide resources for the reporter to ask security questions. (Interview, P20, November 5, 2019, p. 18)