Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

IN A SURREAL SCENE near the end of Black Orpheus, the title character seeks his lost love, Eurydice, in a government building at night. Orpheus sees a janitor pushing a broom toward him from the other end of a long, half-lit hallway; he asks the man to show him the Office of Missing Persons. “This is Missing Persons,” he says. “But there are no missing persons here—only papers.” The janitor beckons through an open door. Papers stacked several feet high lean into each other on a table. “See? Only mountains of paper… You won’t find anyone there. On the contrary, this is where people really get lost.”

The scene draws an eerie portrait of the impossibility of finding information or human value in a bureaucracy bloated with paper. It came to mind recently after a singular decision by the City of Atlanta to release 1.47 million pages of documents to the press and public—on paper. Mayor Kasim Reed announced the release in a February 9 press conference, after weeks of dithering over open records requests by local media regarding a federal investigation into more than $1 million in bribes for city contracts.

Reed, who said he made the decision in the name of “transparency,” may well have set some sort of open records record, according to government accountability experts. “It’s the most I can recall,” said Joey Senat, associate professor at the Oklahoma State University School of Media & Strategic Communications and author of a book on open records and other areas of media law, in reference to the sheer number of pages.

“I don’t know of another example” of an American mayor releasing so many documents on paper at the same time, said Alex Howard, deputy director of the Sunlight Foundation, the Washington, DC nonprofit organization devoted to government accountability.

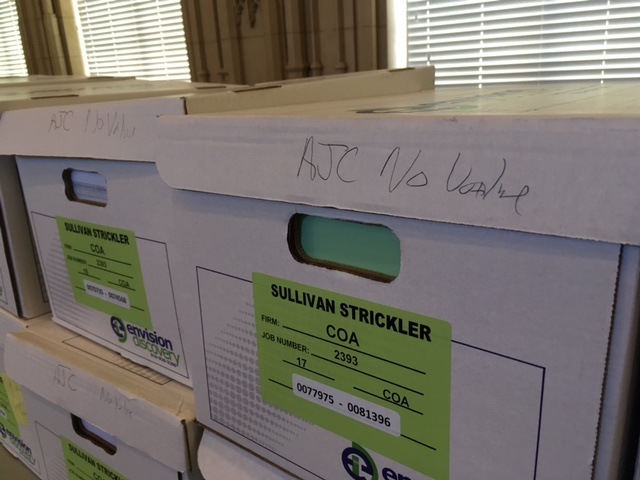

Stacked boxes containing a portion of the 1.47 million pages recently released by the City of Atlanta. Photo by Timothy Pratt.

Apart from the magnitude of the release, there are serious questions about why a major American city in the Wikipedia age would forego the digital route in such a case, the same experts noted. “When you don’t release something electronically, when you don’t enable a search, it does have a relationship to accountability and accessibility,” Howard said.

At the press conference, Mayor Reed said the paper release was due to the need for redacting names and other information. Such a step is not necessary for large cities like Atlanta, given current digital capacities, said Howard. “This means they’re not aware of software to make redactions,” he said.

RELATED: ‘I’ve had it’: Family-owned paper threatens state legislator with lawsuit

Reed’s press conference was staged at the back of the cavernous, second-floor room in Atlanta’s Neo-Gothic City Hall where the City Council once met. As boxes crammed with paper towered behind him, the mayor used much of the half-hour event to distance himself from the bribery scandal, under investigation by the Justice Department and the IRS, and trumpet his record, according to an Atlanta Journal-Constitution report. Reed has a year left to his second and last term.

In the days that followed, the AJC (and other local news outlets) sent a handful of staffers to the same room for hours at a time. Investigative editor Ken Foskett, in his 28th year at the AJC, said he and his colleagues ran across “tens of thousands of empty sheets,” apparently the result of printing empty cells on spreadsheets. There were also microscopic printouts of tables, cramming rows of data into a rectangular space the size of a finger. Some newsroom gallows humor followed: Reporters from several news outlets tweeted about paper cuts and band aids on fingers making it difficult to type.

But slogging through the boxes wasn’t funny. “Being on the receiving end of this, it does not feel like transparency,” said Foskett, who also serves on the board of Georgia’s First Amendment Foundation. He noted that the boxes were labeled with broad categories describing the contents within—mostly, names of people linked somehow to the investigation. Beyond that, the city provided “zero description about what might be in each box.”

A visit to the site brought home the fantastic futility of it all. Marbled stairs lead to a wooden door that opens onto a room full of boxes, overseen by huge tapestries hanging on the high walls, depicting shepherds and their flocks. A pair of city employees sitting off to one side, paid to “watch over” the million and a half sheets of paper. Until when? I ask. Shoulders shrug.

By the time I arrived, reporters such as AJC columnist Bill Torpy had spent hours feeling, he said, “like a monkey trying to play the accordion.” Some had marked certain boxes in pen with reminders—and, perhaps as a warning to others—of their contents. The notes said, “blank pages,” “blank,” and “tiny spreadsheets.” Many said, “No value.”

The problem is not just a procedural one for reporters. “This is an insult to the people of Atlanta,” said Senat, of Oklahoma State. In his press conference, Mayor Reed said the “documents are being made available free of charge in the public interest.” But if it’s exceedingly difficult for reporters to go through a set of public records due to the sheer amount of paper and the inability to search for terms electronically, then it’s even more difficult for members of the public to do so.

“It’s unquestionable that when a database of documents goes online, much more people can look at it,” Howard said. “If your intention is to be transparent to the public, your first step should be to give maximum exposure.”

The Sunlight Foundation official also noted that the case raises the question of the city of Atlanta’s tech capabilities. “Is their choice [to release the documents on paper] driven by lack of human or technical capacity, or incompetence?” Howard asked. He added that his organization helps local and state governments increase their openness and accountability in a digital age. “Mayors who are not stepping up to this aspect of 21st-century government are leaving something on the table,” he said.

CJR asked Mayor Reed’s staff for an interview before publication and was instead provided an email that failed to answer a question about how much taxpayers had paid for all this paper. The same email maintained that the initial delay of the release owed to the city wanting to maintain the “confidentiality of records related to that open criminal investigation.”

A spokesperson wrote that the city had already digitized more than 350,000 pages in a searchable format “less than a week following” the paper release on February 9, and would upload a total of 1 million pages by February 24. “All documents will ultimately be made available online,” the email continues, without offering a timeline.

But as of February 21, the AJC’s Foskett said, the total number of searchable digital pages was “nowhere near 350,000.” As for when the city would make a million pages available online, he added, “We’re not holding our breaths.”

In the end, perhaps nothing is wholly open or transparent. Even after a city staggers toward some show of transparency, reporters still have to decipher how that city makes its decisions, and who benefits most. Even 1.47 million pages—in print, or online—can’t always answer that.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.