Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Nine days after the Investigative Reporters and Editors organization bestowed its highest honor on Ukrainian reporter Dmytro Gnap and his colleagues, Gnap announced he was quitting journalism to run for the presidency of Ukraine.

“I’m really tired from this absolutely crazy situation where we are exposing dozens of corrupted officials and nothing happens,” Gnap said during an interview in Kiev on July 3, a few days after his announcement. “No one went to jail. Not a single one.”

Gnap and his investigative team spent years producing stories about the shady business deals of politicians, including reports that linked President Petro Poroshenko to offshore accounts—with little to no effect. Gnap’s team at Slidstvo.info, an investigative reporting NGO backed by Western grants, along with the Organized Crime and Corruption Report Project, won the IRE Medal for best investigative journalism for their 2017 documentary “Killing Pavel.” In the 50-minute documentary, Gnap, the lead reporter, presented evidence that Ukraine’s secret police may have played a role in the car bombing of Ukrainian journalist Pavel Sheremet.

“If I was an investigative reporter in Canada, Belgium, or Sweden, I would work to old age because the systems in those countries work,” says Gnap, 40, who is married with three children, ages 4 to 16. “But I’m living in Ukraine. I’m Ukrainian. I don’t want to keep waiting for someone to come and change our country and establish justice. We have corrupted officials. We have very weak public services. And someone needs to change this.”

Gnap compares his decision to that of witnessing a robbery on the street. As a journalist, he could decide to film the robbery, call for help, or intervene himself. “I’m not going to keep filming the robbery of my country,” he says.

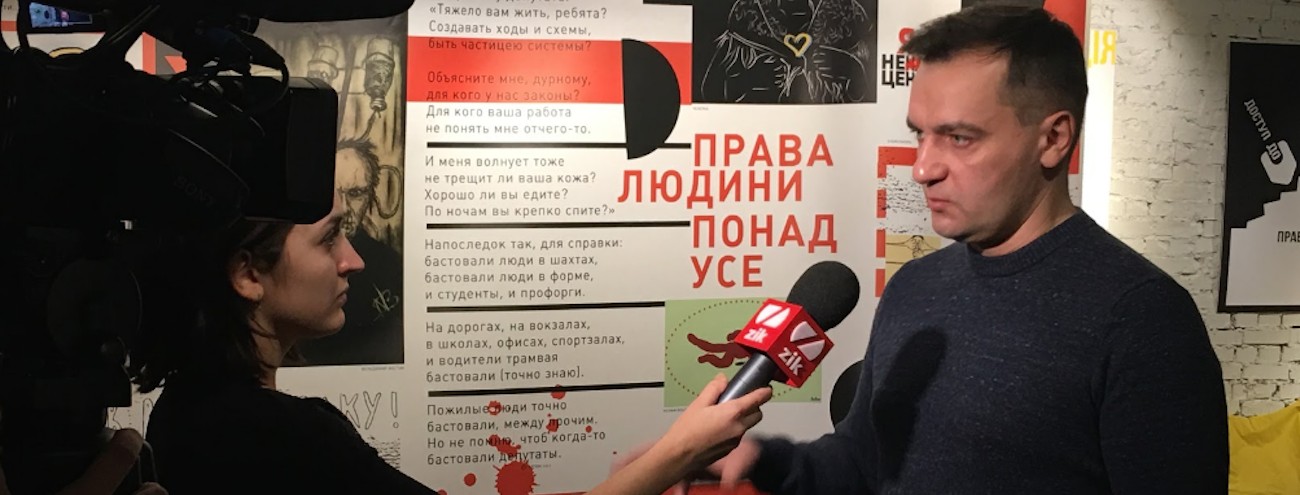

Dmytro Gnap in Kiev just days after he announced he was running for the presidency of Ukraine. Photo: Cheryl L. Reed.

Gnap has entered a crowded presidential contest where at least eight expected contenders are old faces on Ukraine’s political stage. Yulia Tymoshenko, who co-led the Orange Revolution of 2004 and was the country’s first female prime minister, has a slight lead in the polls. Nearly half of the respondents said they definitely wouldn’t vote for the current occupant.

Ukraine’s presidential election, which will take place in March of 2019, is the first regular election since the Euromaidan Revolution ousted President Viktor Yanukovych in February of 2014 and quick elections put Poroshenko in power three months later. Poroshenko’s popularity has since waned as critics say he has been slow to make reforms and fix Ukraine’s many social problems. A June survey showed 76 percent of those polled believe the country is going in the wrong direction under his leadership.

Gnap wants to capitalize on that dissatisfaction by uniting the opposition democratic parties of several former journalists and activists now in parliament. He plans to run as the single liberal opposition candidate on an anti-corruption platform that promises to clean up government. In addition to extensive reforms, Gnap plans to strengthen the country’s anti-corruption bureau, remove corrupt judges, reform the country’s secret police and help local governments break monopolies that overcharge people—all issues that Gnap, as a journalist, reported on for years.

Gnap’s biggest challenge is getting the word out about his campaign. In the latest political poll, released in early August, Gnap didn’t even rank.

“There is no problem for me with those polls,” Gnap says. “Tymoshenko, Poroshenko, and others have been for many years in Ukrainian politics. Tymoshenko since 1996. Poroshenko since 1998. I started my political career a month and a half ago.”

Though he has been a television journalist for nearly two decades—and is well-known among investigative journalists in Eastern Europe—his reports are shown on small independent media platforms. Most Ukrainians get their news from mainstream television stations, which are owned by oligarchs and politicians—competitors who are unlikely to give Gnap an audience. Not a single major television station in Ukraine covered Gnap’s announcement that he was running for president, he says.

Gnap’s campaign is also being run by a former journalist, Vladimir Fedorin, who was the chief editor of Forbes Ukraine until 2013 when a crony of Yanukovych’s bought the media outlet and implemented censorship. “Radical reforms are impossible without a real political process,” says Fedorin, who also runs a free market think-tank in Ukraine. “Ukrainian political life needs disruption, needs new leaders who won’t tolerate business as usual of cronyism that steals opportunities from the whole nation.”

Gnap and Fedorin say his grassroots campaign will emulate the internet-focused campaigns of former President Barack Obama and French President Emmanuel Macron. Like those upstarts, Gnap, with his direct gaze, charcoal and silver hair, unlined face, and booming voice knows how to charm a television audience.

“I have some romantic goals,” he admits, “of showing the Ukrainian people that changes are coming and that people outside the political system are finally coming to power.”

Journalists as politicians in Ukraine

Gnap isn’t the first journalist in Ukraine to enter politics. Mustafa Nayyem, a Ukrainian investigative journalist credited with starting the protests that led to the Euromaidan Revolution in 2013-2014, was elected to Ukraine’s parliament in 2014 along with two other noted investigative journalists, Sergii Leshchenko, and Iegor Soboliev. Gnap is in talks with those ex-journalists to form a new independent political party.

Soboliev, who for 18 years worked in various TV and online platforms, says he left journalism because “I was deeply disappointed that after our investigations there were no proper punishments or even improvements.”

Journalists turned politicians aren’t without controversy. In the summer of 2016, critics questioned how Leshchenko could afford to buy an apartment for $281,000 when the average monthly salary in Ukraine in 2016 was about $200. Leshchenko said he earned the money from various sources, including Western grants he received for his investigative stories.

Yevhen Fedchenko, director of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy School of Journalism and a former board member of Hromadske TV, called Leshchenko’s explanation “dubious” and says he’s disappointed by the journalists who’ve entered parliament. “We lost some good journalists but never got new MPs capable of making changes.”

Fedchenko has been a critic of Gnap’s journalism, calling him a politician in a piece in CJR last year. The two have not spoken since. “Everything Dmytro was doing before now was more related to his politics than journalism,” Fedchenko says. “It would be more just if he would call it what it is and not masquerade political activism as journalism.”

In the past four years, many of Gnap’s investigative pieces focused on business dealings of President Poroshenko and his friends, causing some critics to claim Gnap was partisan. Gnap insists his reporting was never biased.

“Concentration on corruption could make some people think you are an activist,” Gnap says. “But Slidstvo focused not only on corruption but on criminal cases and social problems. We made some mistakes and we had some weak points in our journalism and we tried to fix them and to improve our work.”

He shrugs at Fedchenko’s criticism that he had political ambitions all along. “He produced a correct forecast. Now is he interested in being right or changing Ukraine?”

Whispers of political ambitions

As far back as 2014, Gnap’s colleagues and friends teased him about his presidential ambitions after he made a fiery speech at the Euromaidan protests, accusing opposition leaders of having betrayed the people of Ukraine. One friend even made T-shirts that said, “Gnap for President” and created a campaign poster from Barack Obama’s famous Hope photo, replacing Obama’s face with Gnap’s.

“It was a running gag, I am afraid, among the Hromadske team that Dima will run for president,” said Katya Gorchinskaya, CEO of Hromadske TV, the cable and online news platform that Gnap helped start in 2013. “It was an open secret that he had political ambitions. It’s a shame to lose his skills and knowledge, but this process is extremely common in Ukraine and you can more or less predict it at every election cycle.”

Hromadske, which means public in Ukrainian, started just before the Euromaidan Revolution —known in Ukraine as the “Revolution of Dignity.” The online platform benefited from a young audience who donated thousands of dollars to keep Hromadske going as it live-streamed violent clashes in which more than 100 people, many of them civilians, were killed.

“The 2 million to 3 million people who supported and participated in civic protests during the Revolution of Dignity, those are our supporters and we can count on them,” Gnap says.

Gnap’s core audience are middle-class social media users, from 24 to 40 years old, he says. He currently has over 82,000 followers on Facebook. Gnap supports LGBT rights, thinks that abortion should be legalized, and believes Ukraine should stop providing free services because it opens up too many opportunities for corruption. An atheist, he wants to reduce the power of the church in Ukraine. And he thinks English should become the official second language. While those stances may win him votes from a younger, more modern generation, they are unlikely to make him popular with older, religious Ukrainians, nostalgic for the comparatively well-run Soviet Union, who depend on the government for their pensions and medical care.

When critics argue that Gnap doesn’t have the experience to run for office, he points out that the most corrupt politicians—including Yanukovych who is accused of stealing billions from the country’s treasury—had decades of experience. “Experienced professionals have brought Ukraine to poverty and corruption,” he says.

If his bid for president fails, Gnap says he’ll run for parliament next year. “I want to sacrifice my life for this. I decided to change my comfortable life as a journalist for fighting for real change in Ukraine. This is just the start.”

RELATED: In a time of war, investigative reporting in Ukraine is a tough sell

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.