Davos Fareed Zakaria speaks at the 2013 World Economic Forum in Switzerland (Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

Davos Fareed Zakaria speaks at the 2013 World Economic Forum in Switzerland (Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

Some of Fareed Zakaria’s past and present publications are finally facing the music, even though they won’t acknowledge what it sounds like. Plagiarism accusations have dogged the CNN host and Washington Post columnist for years, though the drumbeat has crescendoed in recent months. Corrections and apologies have been added to a wide array of his previous work. But Zakaria appears in no danger of losing his prestigious jobs. Outcry within the journalistic community, meanwhile, has been unexpectedly mute, with many discussions focused on the semantic question of whether Zakaria’s mistakes constitute what some news organizations consider an unforgivable sin.

Zakaria’s high-profile case underlines the media’s long struggle with plagiarism — just not the struggle you’d expect. A review of examples from the past quarter-century shows that journalists have continuously grappled not only with the definition of plagiarism, but also how to respond to it. Punishment has been consistently inconsistent. And opinions vary on whether such sinners should be allowed back in the church. All of this comes as digital journalism continues to redraw the boundaries of originality, and the ease with which plagiarism is spotted continues to grow.

“Fabrication, obviously, is very black and white,” said Teresa Schmedding, president of the American Copy Editors Society and a deputy managing editor at the Daily Herald in Illinois. Such was the case with onetime New Republic scribe Stephen Glass, subject of a profile in the magazine’s recent anniversary issue, and Jonah Lehrer, an ex-New Yorker writer whose book deals grabbed headlines last week. “When it comes to plagiarism and punishment for it, the reason it’s so difficult is that it is more grey.”

And it always has been. A CJR cover story in 1995 analyzed 20 cases of plagiarism in the previous seven years, concluding, “Punishment is uneven, ranging from severe to virtually nothing even for major offenses.” Laura Parker was fired from The Post in 1991 for lifting quotes from the Associated Press and Miami Herald. Denver Post columnist Ken Hamblin, meanwhile, was suspended for two months in 1994 after he copied five paragraphs from a Rocky Mountain News report. “The sin itself carries neither public humiliation nor the mark of Cain,” CJR’s Trudy Lieberman wrote. “Some editors will keep a plagiarist on staff or will knowingly hire one if talent outweighs the infraction.”

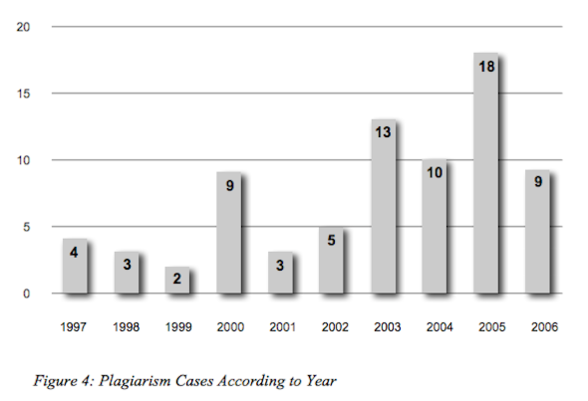

A University of Maryland study found similar ambiguity in 76 newspaper plagiarism cases between 1997 and 2006. Forty-three of those offenders — 56 percent — lost their jobs, with the rate of punishment steadily increasing from minor to major to repeated infractions. Perhaps more interestingly, the papers’ word choice in publicly responding to those crimes largely correlated with their eventual sanctions — “plagiarism” typically garnered termination while synonymously described offenses earned lesser punishments.

A September analysis by Politico reporter Dylan Byers and two media ethics experts argued that Zakaria had indeed plagiarized a number of articles by “patch writing,” small changes to language that mask theft of larger ideas. “Case by case, the examples here qualify more as violations or misdemeanors than serious crimes,” Byers wrote. “But taken together, they show an undeniable pattern of behavior.” Disputing such behavior is a hard case to make without more details from Zakaria. The writer and TV host has remained relatively silent other than an August email to Politico rebutting some of the charges. He and CNN did not respond to emails seeking comment for this story.

On Nov. 7, Newsweek added editor’s notes to seven of Zakaria’s columns from 2001 to 2010, saying they “borrowed extensively” from other sources “without attribution.” Slate did the same just days later for a 1998 article that “failed to properly attribute quotations and information.” After Our Bad Media last week highlighted questionable Zakaria pieces in The Washington Post, editorial page editor Fred Hiatt acknowledged “problematic sourcing” in five of those columns and has since amended four of them with editor’s notes.

The actions came two years after Zakaria was briefly suspended by CNN and Time for plagiarizing a column on gun control — a “terrible mistake,” he said in a statement then. Similar allegations have piled up this year, thanks largely to Our Bad Media’s anonymous watchdogs. Yet Zakaria has remained on air at CNN and in The Post’s opinion lineup, despite the organizations’ harsher punishment in recent years for similar ethical lapses. What’s more, the media outlets that publicly reprimanded Zakaria have been loathe to use the “p” word in describing his missteps.

Jacob Weisberg, head of the Slate Group, defended Zakaria’s mistakes as “minor, penny-ante stuff” unworthy of the “plagiarism” label, according to The Daily Beast. “I’m not sure we have a strict operational definition of plagiarism at Slate,” he added in an email to CJR. “To me, plagiarism involves not just using someone else’s research or ideas without credit, but also taking passages of prose and distinctive language.”

Hiatt cited a similar definition in an email, calling plagiarism “the practice of taking someone else’s work or ideas and passing them off as one’s own.” The Post’s correction atop a 2011 Zakaria column, for example, apologized for wording that was “taken from, but lacked proper attribution to” a 2011 article in Foreign Affairs. Though Zakaria indeed cited the piece at the beginning of one paragraph, he did not subsequently do so when using its language — nearly word for word — in the following sentence.

“I’d say the reader should have been told that those were not [Zakaria’s] words; but given the citation immediately preceding, it’s hard to argue that [Zakaria] was trying to claim credit for this idea or pass someone else’s ideas off as his own,” Hiatt said. “That’s why I think improper attribution is the more accurate description.”

Editor’s notes on The Post’s other Zakaria columns in question likewise apologize for poor attribution. Hiatt said he evaluated the seriousness of the infractions and the time period in which they occurred — before the writer’s admission of a “terrible mistake” in 2012 — when deciding how to respond. “But if someone did commit a firing offense, no amount of talent could ‘outweigh’ that,” he added.

In the past three years, the newspaper has similarly copped to “material borrowed and duplicated, without attribution” in a handful of news stories, including two by Sari Horwitz in 2011 and another by William Booth in 2013. The former lifted a combined 12 paragraphs in whole or part from the Arizona Republic, while the latter pulled four sentences from a scientific journal. The newspaper’s media reporter, Paul Farhi, described only Horwitz’s case as ”plagiarism,” while then-ombudsmen Patrick B. Pexton labeled both as such. Horwitz and Booth were each suspended for three months without pay.

The Post is by no means alone in this apparent haziness. In July, The New York Times posted an editor’s note below a Carol Vogel piece that “improperly used specific language and details from a Wikipedia article without attribution.” Its news coverage of the case mentioned only “allegations of plagiarism,” even though Public Editor Margaret Sullivan was more forthright with the term. Of course, The Times this year also amplified “plagiarism” charges against author Rick Perlstein and used the label to describe BuzzFeed’s firing of Benny Johnson, who was sacked for copying information from Wikipedia, among other sources.

To be sure, no two cases are entirely alike. But the responses by Zakaria’s legacy publications contrast starkly with BuzzFeed’s handling of Johnson. Editor Ben Smith’s written apology to readers used the word “plagiarism” five times. He added in a Duke University talk published by Poynter last week that “[p]resenting someone else’s words as your own is such a basic form of dishonesty.” Johnson has since been hired by National Review. And BuzzFeed appears to have moved on from the scandal.

Such institutional admissions “might actually help move the process [of recovery] along,” said Andrew Seaman, chair of the Society of Professional Journalists’ ethics committee and a Reuters reporter. “Otherwise, it’s like plugging a thousand leaks in a dam: It’s not practical and it may make the structure even less sound.”

News organizations indeed address some allegations head-on. In 2003, The Times responded to Jayson Blair’s serial plagiarism and fabrication with a 7,000-word investigation describing “a profound betrayal of trust and a low point in the 152-year history of the newspaper.” Blair was an outlier, of course, perhaps the most prolific case in recent history. But The Times’ response may prove to be a model in an era when anyone — not least anonymous bloggers — can detect plagiarism.

“I don’t think it’s necessarily easier to do it, because journalists have always had access to tools with which they could pick up other information,” Blair said in an interview with CJR. “What has changed dramatically is the ability to catch it.”

Blair didn’t equate Zakaria or other recent examples to his own journalistic crimes, which he summed up as “a very big case.” But in previous instances where journalists were shown mercy, he added, “the cases have always been examples of plagiarism in which you could understand how people made those errors. In [Zakaria’s] particular case, we’re not getting a good sense of how these errors were made.”

The Blair influence There was a marked uptick in reported plagiarism after Jayson Blair made headlines. Source: Lewis, Norman (2007). “Paradigm of Disguise: Systemic Influences on Newspaper Plagiarism.” Doctoral dissertation. University of Maryland, College Park.

The Blair influence There was a marked uptick in reported plagiarism after Jayson Blair made headlines. Source: Lewis, Norman (2007). “Paradigm of Disguise: Systemic Influences on Newspaper Plagiarism.” Doctoral dissertation. University of Maryland, College Park.

Now a life coach in Virginia, Blair hypothesized that responses to plagiarism are cyclical in nature, with crackdowns coming after huge scandals like his and lesser sanctions filling the lulls in between. The numbers seem to back him up. The University of Maryland study, which surveyed plagiarism from 1997 to 2006, found the rate of reported instances tripled after Blair’s fabulism received frontpage treatment. Sanctions likewise increased in severity. Poynter Institute’s Kelly McBride also observed a post-Blair uptick in firings, according to a 2011 Poynter article, though that appeared to taper off once newsrooms began grappling with growing financial hardships. “My sense is [editors] feel like they are partially culpable for creating an environment where mistakes and plagiarism are more likely to happen,” McBride said at the time.

Absent the “Blair influence,” news organizations often play definitional games when plagiarism allegations appear less egregious or clear-cut, said Norman Lewis, who authored the plagiarism study and now researches the topic at the University of Florida.

“We save the ‘plagiarism’ word for when we think it’s a really nasty thing,” added Lewis, a former copy editor at The Post. “That suggests plagiarism occurs when it’s only a capital offense. And when it’s not a capital offense, it’s not plagiarism. We should have an expansive view of plagiarism. We should not be afraid to call it what it is. That doesn’t mean that it’s a fireable offense. It’s an error that should be corrected like any other error. But let’s separate the sanctions from the definition.”

David Uberti is a writer in New York. He was previously a media reporter for Gizmodo Media Group and a staff writer for CJR. Follow him on Twitter @DavidUberti.