Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Midway through dinner on March 29, 2023, at an Italian restaurant in Washington, my phone buzzed. It was Emma Tucker, the newly appointed editor in chief of the Wall Street Journal and my boss. I excused myself from the other guests, journalists, and dignitaries brought together by a tech CEO, and dashed into the small courtyard.

“Evan Gershkovich has gone missing,” Tucker said. “What can we do?”

At the time, I was the Journal’s Washington bureau chief, and so was best placed in the newsroom to engage the Biden administration as we sought to find out what happened to our colleague. Few at the Journal in the US had met Gershkovich since he had joined the paper just over a year earlier as a correspondent covering Russia.

Tucker said Gershkovich had missed two check-ins over the past several hours. What we knew from our corporate security team suggested that he might match the description, just emerging in some Russian reports, of a man hauled out of a steakhouse by government agents in Yekaterinburg, an industrial hub more than a thousand miles from Moscow where Gershkovich was reporting on the state of Russia’s wartime economy.

My next ninety minutes was a flurry of calls: State Department, National Security Council, Pentagon. The message: we believe our colleague has been seized by Russia’s security services, and we would like to speak to officials at the highest level tonight to convey the seriousness of the situation and ask for their assistance in seeking his return.

Or, more simply put: this looks really bad and we want your help.

During a brief return to the dinner table, the other journalists assumed I had been editing a big scoop that was about to light up their phones, and they started discreetly pressing me about my absence. “Internal matter,” I mumbled and left.

Before the night was over, Tucker and I had received calls from Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Deputy National Security Adviser Jon Finer, among others. They offered essentially the same response: we hear you, this is a bad situation, and we will do everything we can to help.

It was as reassuring as it could be. Then, a few hours later, the Kremlin took away any hope that there may have been a misunderstanding or that Gershkovich might miraculously reappear unscathed. A Russian government statement said Evan Gershkovich, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, had been detained on suspicion of spying. He was transferred to Moscow, where he entered the infamous Lefortovo prison, renowned for isolating and disorienting its inmates and the place where many of Russia’s most famous dissidents had been incarcerated.

The only sliver of positive news was that Gershkovich was alive and in custody. But it thrust the Journal into its greatest crisis since the kidnapping and murder of South Asia bureau chief Daniel Pearl in Pakistan more than two decades before. The question we faced was: How should we respond?

The Dynamic over Hostages Has Shifted

Gershkovich was the first American journalist to be charged with espionage by Russia since Nicholas Daniloff, a US News & World Report correspondent in Moscow during the Cold War.

Gershkovich was also the latest in a long succession of US journalists intermittently seized on false charges or taken hostage around the world over the past forty years, going back to Terry Anderson of the Associated Press, who was kidnapped in Beirut in 1985 by Iran-backed Shiite jihadists and held for six years.

Whenever a Western journalist is seized, it leads to a difficult and emotional interplay between the hostage’s family, the hostage’s representatives or employer, the government they usually depend on to negotiate the captive’s release, and the hostage takers themselves.

It also has the knock-on effect of chilling press freedom more broadly. Gershkovich’s arrest prompted a swift exodus of other Western and independent journalists from Russia, which was presumably valuable to the Kremlin as it struggled to prosecute the war in Ukraine and to eradicate domestic opposition.

During the first fifteen years of the twenty-first century, the most prevalent hostage takers were Islamist jihadist groups in the Middle East and South Asia, who were responsible for the murder not only of Pearl but of US journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff in 2014, as well as several aid workers.

Western governments adopted different approaches when their citizens were seized, as chronicled in “We Want to Negotiate,” a 2019 examination of the phenomenon by Joel Simon, former executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists and now director of the Journalism Protection Initiative at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.

Many continental European countries, including France, Spain, and Italy, made concessions or paid ransom reportedly in the millions of dollars for the return of hostages, Simon writes. The British and US governments took the line that negotiating only encouraged more hostage-taking and so flatly refused.

There also emerged a pervasive sense that the response to such hostage-taking should be carefully and cautiously calibrated. Negotiations over the hostage’s release should ideally be done quietly and without publicity, the thinking went, so that the “price” of freedom would not escalate, further rewarding the captors for their crime.

“Public protests can have a perverse effect by driving up ransom demands and complicating negotiations,” Simon writes. “Worse, they can enhance terrorist propaganda.”

Still, the highest-profile recent seizures of American journalists have come at the hands not of extremist organizations, but hostile governments looking for leverage over the US. Every case and circumstance is different, of course, but that shifting dynamic challenges the conventional wisdom that keeping a low profile is always the wisest course of action.

The involvement of governments has thrust those seizures more deeply into the realm of US national security policy. The government that seizes the hostage gains an immediate advantage over the government representing the hostage, initiating a battle of wits in which the captive becomes a pawn in the broader game of interstate relations.

When, in July 2014, the Iranian security forces seized Jason Rezaian, Tehran bureau chief of the Washington Post, and his wife, Yeganeh, and falsely accused them of espionage, it was seen as part of an internal power struggle in Iran over the proposed international pact aimed at curbing the country’s nuclear advances. Yeganeh was released after three months; Jason was freed in January 2016.

In a September 2023 prisoner swap that saw five Americans freed from Tehran and five Iranians in US custody returned home, the US unfroze $6 billion in Iranian funds.

In recent years, US policy toward negotiating for its citizens’ release has changed, too, with executive orders and then an act of Congress known as the Levinson Act, named for former FBI agent Robert Levinson, who went missing in Iran in 2007 and was declared presumed dead in 2020.

The new apparatus included the creation of the Office of the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs, a unit within the State Department known as SPEHA. Its responsibility is to secure the return of US citizens held abroad.

Cases are referred to SPEHA after a State Department review that establishes whether a citizen has been “wrongfully detained” (as opposed to being held on credible charges) based on eleven criteria. Those include whether the US has credible information the detainee is innocent and whether the detention has been deemed a means for influencing US policy. If an American charged overseas fails to meet the threshold, they remain assigned to consular affairs.

Some Americans seized by Russia before Gershkovich had been declared wrongfully detained and were ultimately released in swaps. Former US Marine Trevor Reed was swapped in early 2022. Basketball star Brittney Griner was released later that year in an exchange that returned arms dealer Viktor Bout to Russia.

Much has been written about the incentives such swaps may create, especially those that trade innocent Americans for Russians guilty of serious crimes abroad. It is akin to the concern that paying ransom leads to more kidnappings.

From the Journal’s perspective, that was a theoretical debate for another time. Our colleague, who was accredited as a foreign correspondent by Russian authorities, had already been seized. We had to do everything possible to get him out, as well as to help him in prison and to support his family.

Since hostages held by hostile governments are now central to US national security policy writ large, part of that effort meant ensuring Gershkovich’s case remained front and center in the minds of US policymakers. We would not conduct any negotiations with Russia. But we could provide support, and if necessary apply pressure, to those we expected to do so.

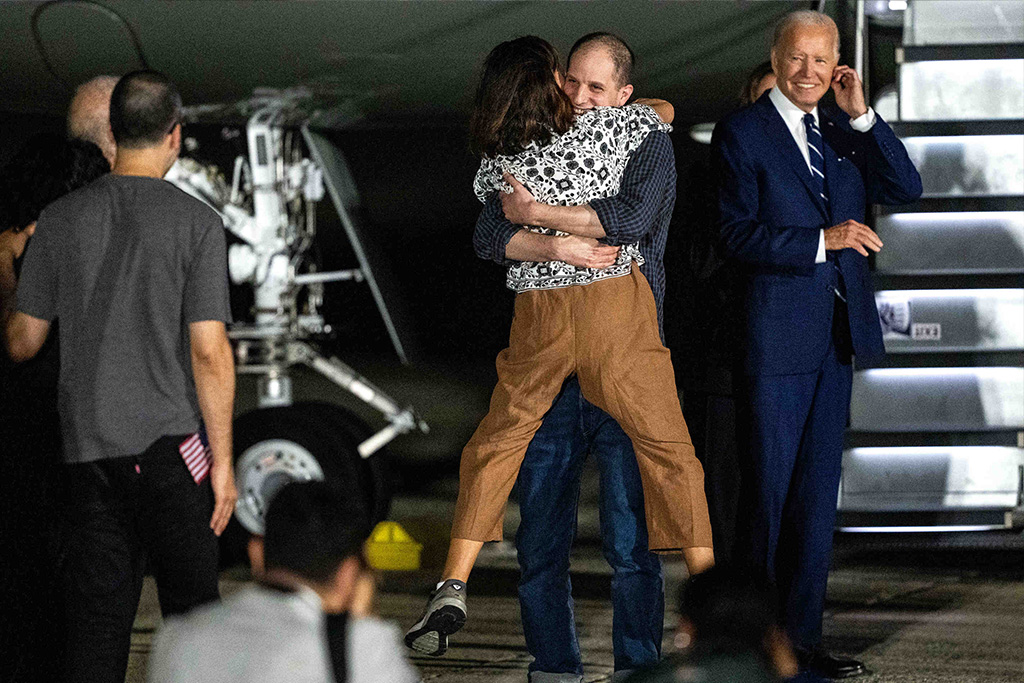

Some sixteen months later, on Aug. 1, Gershkovich was released along with fifteen others, including another journalist, Alsu Kurmasheva of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and several Russian political prisoners in the largest US-Russia prisoner swap since the Cold War. Eight Russian operatives returned to Moscow.

Most newsrooms, the Journal included before Gershkovich’s arrest, have limited knowledge of this terrain. Almost none have reporters dedicated to covering hostile acts against journalists or broader issues of press freedom.

Reporters are trained in how to avoid danger in war zones and protests, how to protect their communications in autocratic countries, and how to handle themselves if they are kidnapped. There are drills for fires and active shooters. Less attention has been paid to what to do when an American reporter is seized by a hostile government and falsely accused of a serious crime.

Yet it is safe to say that, based on the history of the past forty years, this will happen again. When that day comes, hopefully the Journal’s experience, spelled out in detail here for the first time, can aid those responsible for bringing their colleague home.

A State Department Designation Is Important

As in any crisis, the first few days were vital in setting the course for what we immediately suspected would be a long road ahead.

The fact that the Kremlin had announced Gershkovich’s arrest made the possibility of keeping it under wraps a moot point. A false accusation had been broadcast worldwide.

There was little precedent within the Journal to guide us, though Rezaian and others at the Post and elsewhere offered valuable advice. The Journal editors who sought Pearl’s freedom and dealt with the dreadful aftermath had almost all moved on. Since then we had dealt occasionally with reporters detained for a few days, but this was of a very different order.

Given the new dynamics in hostage-taking, the question remained how aggressive we—and our legal and commercial colleagues at Dow Jones & Co.—should be in highlighting Gershkovich’s plight and pushing the administration to act. Were discretion and caution the order of the day, or would trumpeting the injustice that had been meted out on our colleague accelerate his return?

A phone call to a senior government official who knows this terrain provided the answer: “There are times to be quiet and there are times to be loud—and this is a time to be loud.”

“Be loud” was adopted as a mantra. There would later be times when we turned down the volume because negotiations were at such a sensitive stage that publicity might be counterproductive. Otherwise, volume up.

The next challenge we faced was countering the false assertion by Russian authorities that Gershkovich was a spy.

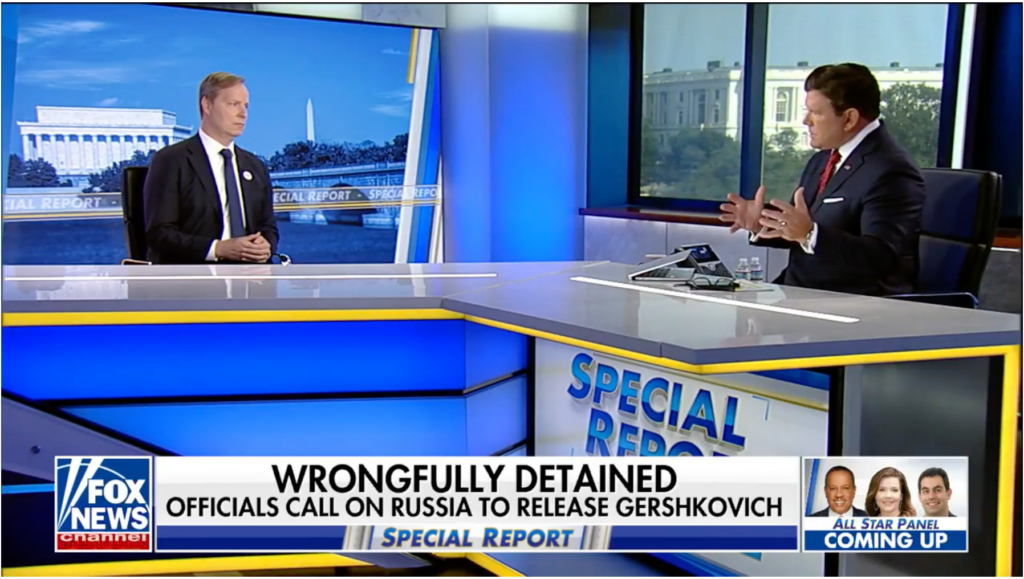

At our request, Sen. Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat and the chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, joined the White House in calling on Russia to release Gershkovich and confirming that he was not a spy.

We repeatedly said the same in interviews and news stories. In dozens of calls in those first few days, we asked other news organizations, press-freedom outfits, writers’ groups, members of Congress, religious and civil-society organizations, foreign governments, think tanks, journalism schools, and anyone else we could think of to do the same while also calling for Gershkovich’s release. Many other friends and supporters did so as well. We blasted it on social media.

Yet over the next sixteen months, I was occasionally approached by people who, after expressing their sympathy for the situation, would inquire slyly as to whether he really only worked for us. I hope the combination of disappointment and anger in my answer finally convinced them.

Securing the “wrongfully detained” designation from the State Department would not only put the case in the hands of a unit dedicated to Gershkovich’s release, it would signal publicly that the administration didn’t give the charges against him any credence.

And it would add an extra dimension of credibility to the hundreds, if not thousands, of stories being written about Gershkovich around the world. To the line “Russia has charged Gershkovich with espionage, which the Journal and the US government vehemently deny,” could be added: “and the Biden administration has designated him as wrongfully detained.”

After four days, Blinken said publicly that he had no doubt Gershkovich had been wrongfully detained, a promising sign. State Department officials, however, continued to say the designation was only under consideration. A week later, on April 10—twelve days after his arrest—it was granted.

That was record time, and in the interim the administration made several calls for Gershkovich to be released. But it also meant that one official and high-profile way to counter the Kremlin’s false story about Gershkovich wasn’t issued by the US for almost two weeks, an eternity in a crisis. And overall the designation process remains opaque and grants significant discretion to officials if and when to apply it, a topic that recently has attracted the attention of Congress. The National Press Club in Washington has called for the designation to be applied presumptively to any American journalist charged with espionage overseas.

Strong Ties with the Family Are Key

The difficult task of informing and engaging Evan’s parents, Ella Milman and Mikhail Gershkovich, and his sister Danielle fell to Tucker and to Liz Harris, the Journal’s managing editor, who had joined the paper upon Tucker’s arrival from London. The Gershkovich family—émigrés from the former Soviet Union—lived in Princeton when Evan and Danielle were growing up but had since moved from New Jersey to Philadelphia.

It was the beginning of a relationship that would make Evan’s parents and sister, supported by the Journal, his greatest and most effective public advocates and central to his eventual release through their appearances, lobbying of high-profile people, and targeted interviews on television.

But there was no guarantee of that then. In fact, I had been told by others with hostage experience that the opposite was likely to happen: families at some point turn against the company, impeding efforts on both sides.

The list of to-dos seemed endless, starting with securing Evan’s permission, from prison, to give his parents power of attorney to act on his behalf to deal with bank accounts, social media, and other personal matters. Rent needed to be paid. The IRS needed to be engaged so it wouldn’t punish Gershkovich for not filing a tax return. The Gershkoviches needed time away from work to deal with the terrifying reality that their son was a prisoner of Vladimir Putin.

The Journal newsroom, too, had the potential to be a huge contributor to the campaign or a complicating factor, depending on how effectively our colleagues felt we were managing the crisis. Journal reporters operate in tough spots all over the world. Each would surely view our response through the lens of: What would you do for me if I were in similar straits?

That meant providing frequent updates and transparent responses to any and all newsroom questions, however uncomfortable that might be.

On the morning of March 31, two days after the arrest, the Washington bureau held its weekly staff meeting. I stood up to expound on what we knew and what we had done and, much to my surprise, promptly burst into tears. We plowed on anyway for the next thirty minutes (I took the occasional break to gather myself in the hall).

If nothing else, it may have conveyed to people five thousand miles from Moscow how distressing and disgusting the situation was.

A few hours later, I prepared to convey a similar message, albeit in a very different tone, to the Russian ambassador to Washington. I had been told by the embassy he would be available to talk by phone. He refused to take the call.

The Need for Clear Lines and Appropriate Distance

As we moved beyond triage, the contour of sustaining the campaign took shape. We were luckier than most for many reasons: we had a brand name and a global platform to maintain awareness about our colleague; the resources to mount a campaign; and familiarity with the Washington landscape.

The same responsibilities and boundaries as exist in the day-to-day running of the company applied here, too: Almar Latour, the Dow Jones CEO, would be in charge of the overall corporate response. Tucker, the Journal’s editor in chief, would be in charge of the newsroom’s.

Obviously the two sides would coordinate, work together, and, at times, overlap. But it was important that the existing delineations—designed to keep an appropriate distance between the commercial side and the newsroom—apply, even if it was our own crisis and the Journal itself was a big part of a story our reporters were covering.

Separating responsibilities was important for the Biden administration as well. Though Gershkovich’s case had thus far been chiefly handled within State and had been sent to the special presidential envoy, it became clear the National Security Council was in charge.

It was another sign of the degree to which hostage-taking by hostile governments had become a matter central to US national security. Ultimately President Biden would have to approve any deal with the Kremlin to bring Gershkovich home.

Latour, Tucker, general counsel Jason Conti, and I all attended off-the-record meetings at the White House in the early heat of the crisis. But Journal reporters in Europe and Washington were covering Gershkovich as a news story, along with countless other subjects that at times brought us nose-to-nose with White House officials.

To demonstrate that the distinction in our minds between advocacy and news was clear, and to ensure that confidential information helpful to Gershkovich’s cause could be freely shared, Latour and our lawyers took over all official contacts with the White House.

They then treated any inquiries from Journal reporters the same as they would from any other news organization. Even that got tricky at times. On at least one occasion, the administration thought, disapprovingly, that our internal process was leaky when, in fact, our reporters had garnered information themselves from their own government sources.

A few months in, I was offered the position of working on Gershkovich full time. I understood it would be the last of my eleven assignments over thirty-four years at Dow Jones.

Inside the newsroom, a small team worked either full time or a lot of the time on the case.

Emma Moody, the Australian-born head of standards and a longtime Journal editor, was responsible for making sure the internal lines were respected and for communicating with staff.

That role was later taken over by Grainne McCarthy, a senior news desk editor in London, who channeled the newsroom’s volunteer spirit into runs, swims, cookouts, public readings, and other activities to honor Gershkovich. She hosted a weekly call, often joined by Danielle Gershkovich, for all comers in the newsroom to solicit ideas for advocacy and provide updates on Gershkovich’s situation. An internal newsletter McCarthy sent each Wednesday—the day Gershkovich was seized—detailed those efforts and called for a “social storm” to keep raising awareness.

Harris, the managing editor, and Christine Glancey, another veteran editor then in newsroom standards, made frequent visits to Philadelphia for lunch in historic Rittenhouse Square with the Gershkovich family, as did others from Dow Jones legal and communications.

I took on external advocacy, which meant talking and writing about Gershkovich wherever and whenever I could find a forum, from Youngstown, Ohio, to Los Angeles to the opinion page of the London Evening Standard. And I canvassed lawmakers, diplomats, NGOs, businesspeople, current and former officials, and returned hostages for insights, suggestions, or contacts to pass to the lawyers to pursue.

These newsroom efforts dovetailed with the company’s work, from managing the legal case in Russia from afar to fostering the diplomatic efforts to secure his release. We connected most closely on the company side with Ashley Huston, a former Dow Jones communications chief who returned to work on the case, as well as the company’s own lawyers and our outside counsel, Robert Kimmitt and David Bowker at WilmerHale in DC.

Take Every Opportunity to Spread the Word

Our central message called for Gershkovich’s release and characterized his arrest as a broad assault on the freedom of the press, depriving Americans of key facts and analysis they need to make informed decisions.

It was designed to serve as a constant reminder of the US government’s commitment to bring its citizens home and of the values that underpin a democracy without being directly critical of the administration.

We soon identified some marquee events to test it.

In early April every year, financial officials and central bankers from around the world descend on Washington for the spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Many of the countries attending in 2023, days after Gershkovich’s arrest, still had dealings with Russia despite its isolation over the invasion of Ukraine and so were potentially in a position to be helpful. Some sessions were to be moderated by journalists.

Our goal was to make sure that if any official was asked, on returning home, whether America considered Gershkovich’s arrest a big deal, there could only be one answer. So we asked as many journalist moderators as we could reach to mention him.

At the start of an early interview with IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva, Ryan Heath, then of Politico, noted that it was a privilege for him to be there when the freedom of Gershkovich and others was being denied. Georgieva clapped and nodded in agreement and the room broke into applause. Outside the building, members of the Dow Jones journalists’ union held up “Free Evan” and “I Stand with Evan” placards.

It wasn’t sophisticated, and we will never know if it made a difference. But we had demonstrated to ourselves that we could take quick action, boosting morale. If there was any chance to spread the word about Gershkovich, we were going to take it.

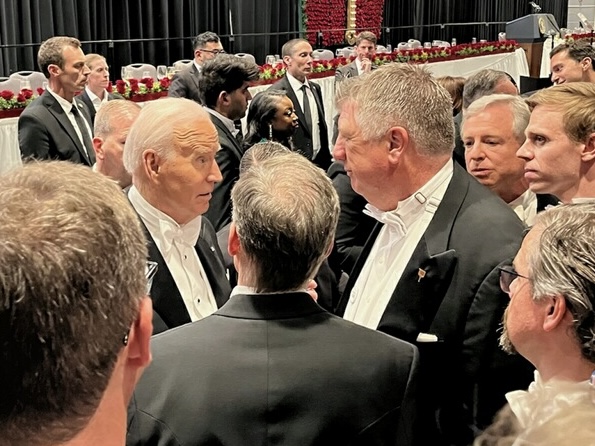

A couple of weeks later, another huge opportunity: the White House Correspondents’ Association annual dinner, where more than two thousand DC worthies in black ties and ball gowns cram into a banquet hall to hear the president roast the press and a hired comedian roast the president. There are serious moments, too, often dedicated to highlighting reporters in distress.

The gala offered the chance for us to make Gershkovich’s case a personal cause for one of the men who held the key to his freedom: Joe Biden. The White House had agreed for Ella, Mikhail, Danielle, and her husband, Anthony, to meet the president.

Before the dinner and after some prep on how to handle the meeting, I took the family down to an anteroom and handed them off to the Secret Service. About fifteen minutes later, they reemerged, relieved. From then on we were able to say that we were counting on President Biden’s personal promise to the family to bring Gershkovich home.

From early on, it was obvious that Putin was looking for only one thing from any swap: Vadim Krasikov, a Russian intelligence operative who killed a Kremlin enemy in a Berlin park in 2019 before being captured and convicted.

Over the sixteen months of Gershkovich’s detainment—and of our vocal campaign on his behalf—what Putin wanted never changed, once again challenging the idea that making noise drives up the “price” of release.

Rather, our efforts were all designed to keep US attention on the case amid a cacophony of international crises, from Ukraine to Gaza. So over the course of the following many months, we tried to keep up a steady drumbeat punctuated with major pushes on important days in Gershkovich’s prison timeline.

In the autumn, I met with staff at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty after they decided to go public with Kurmasheva’s travails, which were escalating after Russian authorities targeted her as she visited her mother. I offered them what we had learned so far in the seven months of Gershkovich’s detention and how they might think about their own campaign.

They later told me they were surprised we were so forthcoming—they had suspected we would see it as against our interests to help another journalist and prisoner. Not only did our hearts go out to Kurmasheva and her family but, in the new era of advocating vociferously with policymakers, it made sense to have an ally and as many voices as possible calling for Putin to release his US hostages.

In early December, Gershkovich reached 250 days of detainment. We relied heavily on our colleagues across the media industry to mark the moment. And they delivered, as they did throughout the campaign. One silver lining to this ordeal was that the national and international press, often at each other’s throats, showed that it can rally as one in support of a worthy cause.

On that day, our colleagues on the commercial side coordinated print advertisements calling for Gershkovich’s release that ran in the print editions of the Journal, the New York Times, and the Washington Post—a rare feat that itself was talked about on cable TV.

We received supportive tweets from Bloomberg, NewsNation, Axios, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and many others. That included a significant blast from our own newsroom, which throughout Evan’s ordeal contributed in exactly the way you would hope a newsroom would, with consistency and creativity.

WSJ.com that day had a “site takeover” that featured the Journal’s own news stories on the anniversary splashed across the top of the homepage with a separate section available in front of the paywall for anyone who wanted to find out more about Gershkovich and his family.

William McCarren, press freedom consultant and staunch ally at the National Press Club, hosted Danielle Gershkovich and me for a morning of satellite interviews where we connected with breakfast shows on local TV stations from Tampa to Minneapolis. CNN anchor Jake Tapper interviewed Ella and Mikhail, then posted about Gershkovich daily on X until he was released eight months later.

Throughout the campaign, we received valuable support beyond the news business as well.

Evan’s friends, many of them reporters who left Russia after he was arrested, organized a channel for letters to reach him.

Given the Journal’s focus, we asked business groups and individuals who were in contact with the administration to add in their conversations that having an American employee of an American firm imprisoned on false charges overseas was a worry for all US companies that operate around the world. In short, it was a weak look for a country seeking to project power around the globe.

One place we struggled was in engaging celebrities. A couple—Sting and Julia Louis-Dreyfus—amplified our message at Gershkovich’s hundred-day mark. But that was pretty much it. Other colleagues tried other leads. Agents professed willingness to help. Suffice it to say that Gershkovich’s ultimate release happened almost entirely unassisted by celebrity star power.

Be Ready for Setbacks and the Long Haul

By the end of 2023, there were murmurs of a possible swap. Given that Germany held Krasikov, the man Putin wanted back, Berlin became a vital actor, adding to the complexity of any deal and once again showing that negotiations over state-held prisoners have become an issue of relations between democracies and autocracies.

Germany had intervened in 2020 to rescue Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny from almost certain death by poisoning. A year later, Navalny chose to return to Russia, where he was promptly detained. He was a much-admired figure in Germany, so a possible trade of two principals—Navalny for Krasikov, with Gershkovich and others added in—seemed a plausible resolution if it could be managed.

But the first few weeks of the new year brought dreadful news: Navalny had died in an Arctic prison camp. The glimmer of a possible deal was extinguished with him. The following stretch was by far the toughest of the campaign. We knew Navalny’s death could prompt the German government to retrench and possibly abandon any prospect of giving up Krasikov.

Gershkovich’s circle of friends centered on Berlin—many of them had moved there from Russia after his arrest—and Journal colleagues in the same city jumped on calls almost weekly to discuss where things stood in Germany and what we could do.

It was an important connection to Gershkovich and his work. Through his friends and family, we pieced together a portrait of a colleague most of us had never met.

Soccer star at Princeton High School. Graduate of Bowdoin College in Maine. Reporting assistant at the New York Times. Then the big move: decamping to Russia, where Gershkovich put his Russian language skills to use and explored his heritage in a vast, fascinating country.

Friends from every stage of his life were involved in the effort to bring him home, which spoke to what his family often described as his innate ability to connect with people. The friend group in Berlin spread word in the German media about why his arrest was important. And they helped ensure that Gershkovich was prominently featured at the 2024 Bundespresseball, a glittering annual gala in Berlin.

Back in the US, Gershkovich was never far from the news. In early March, Speaker Mike Johnson, a Louisiana Republican, invited Ella and Mikhail to be guests at the State of the Union speech, in which President Biden mentioned Evan.

A week or so later, at the annual Gridiron Dinner, another Washington gala, the president talked about Gershkovich in his speech, then lingered in the ballroom as most of the guests filed out. I approached the scrum that had formed around him. He spotted the “I Stand with Evan” button affixed to my white tie and tails and motioned me forward. I thanked him for all he was doing and asked him to keep it up. His immediate response: “Well, we got the Germans on board.”

The one-year anniversary of Gershkovich’s detention in late March came and went with a blitz that surpassed all the previous combined efforts of the company and the newsroom: more than thirteen thousand articles written; more than five thousand broadcast clips; more than a hundred interviews by the Gershkovich family, Latour, Tucker and senior Journal editors; photos of Dow Jones and Journal employees across the world in “I Stand with Evan” T-shirts; and coordinated editorials across the media on the importance of press freedom.

Yet there were many weeks when it seemed like Berlin and Washington weren’t pushing ahead as we had hoped. Whenever we felt the campaign was flagging, we didn’t have to look too far for inspiration. Every month or so, Gershkovich, who turned thirty-two years old in prison, appeared in a glass cage in court. It is hard to imagine what it took for him to display such fortitude, awareness, and occasional humor. It had an energizing effect on everyone in the newsroom working on his behalf. If he could do that, how could we grumble?

As spring turned to summer, the US election campaign began in earnest. We saw a window stretching to about Labor Day to get a deal done before we expected all negotiations to cease and perhaps be resumed by a new administration—many, many months later.

Meanwhile, Gershkovich was transferred for trial to Yekaterinburg, where he had been detained, and was swiftly and predictably convicted, an innocent man sentenced to sixteen years in prison.

The Language in News Stories Matters

How should you characterize a guilty verdict in a trial where the outcome is known in advance, the accused has no access to what we would consider a proper defense, and you know for a fact that the defendant didn’t commit the alleged crime?

We wrestled with that and encouraged other news organizations to wrestle with it, too. The traditional response in a news culture of objectivity would be to state both sides, starting with the action: “A Russian court convicted Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich of espionage,” followed by denials and condemnations from the US government and the Journal of the verdict and of Russia’s legal process.

Was that fair? In a technical way, yes. But it also repeated exactly what the Kremlin wanted the world to believe—that Gershkovich was a US spy—when we knew that was false and had spent more than a year trying to counter the label.

Were we serving our readers with directness and honesty with a headline and lead paragraph that focused on the finding of his guilt? Would readers give sufficient weight to our denials lower down in the story? How would Gershkovich feel reading that story in his own newspaper?

We understood that each news organization would reach its own verdict. Ultimately, our own lead paragraph stated the facts as we knew them, not as the Russian government wanted them to be portrayed: “Evan Gershkovich, the Wall Street Journal reporter falsely accused by Russian authorities of spying, was sentenced to sixteen years in a high-security penal colony, after being wrongfully convicted in a hurried, secret trial that the US government has condemned as a sham.”

Be Ready for Success

The prospect of Gershkovich being shipped off to a penal colony was grim, but Russian authorities signaled that something else might be in the offing by dramatically compressing the timeline of his trial.

We didn’t do much in the way of interviews when the verdict was announced, figuring this was a time when we wanted to be cautious. And we started to think about what to do if Gershkovich was suddenly on a plane home.

How to handle a captive’s homecoming is another area little studied by newsrooms. Yet there are common themes across the experiences of many returning hostages.

The State Department runs a post-isolation program at Brooke Army Medical Center, in San Antonio, to provide medical assessments and help the returnees readjust to basic tasks like choosing what clothes to wear. Then those newly released face the exhilarating prospect of resuming life in the free world.

Inevitably there are later low points and setbacks as the magnitude of their experience comes into focus. They and their families may need counseling and financial aid.

Hostage US, a nonprofit dedicated to returnees, provided useful resources. Former captives such as David Rohde, who was held by the Taliban and now works for NBC News, and Rezaian, at the Post, told us what to expect. Another long list of to-dos was put together, starting with basics like a new phone and laptop.

In late July, everything got really quiet. For the first time in a long time, it looked hopeful.

Early on Thursday, August 1—day 491 since Gershkovich’s arrest—I joined senior Journal editors in Tucker’s office at our New York headquarters. We peered at flight trackers, trying to chart the plane we thought he might be on as it flew from Moscow to Ankara, where we knew a swap of some sort was scheduled to take place. There was also a lot we didn’t know. Was he on the plane for sure? Who else was with him? Who was being returned?

We even wondered if we were watching the right aircraft when the plane we were tracking made a U-turn over Sochi near the Black Sea and started heading back toward Moscow. It later turned out the plane was circling to buy time in a carefully choreographed exercise to have all the planes involved land around the same time.

After about four and a half hours of waiting, we got the news: Gershkovich was free, along with Kurmasheva of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty; Paul Whelan, an American in Russian custody for almost six years; columnist and Russian dissident Vladimir Kara-Murza; and twelve others, including Russian political prisoners.

Germany handed over Krasikov, the assassin, and the US and other allies contributed Russian prisoners in their custody, bringing to eight the number of operatives returned to Moscow. There were twenty-four adults in all, sixteen coming out, eight going back.

The scale and asymmetrical numbers put paid to two ideas that also circulate in hostage discussions: that there should be a pecking order for release based on a hostage’s time in captivity and that Russia will only agree to one-for-one swaps.

To no one’s surprise, tears flowed widely in the newsroom then. But this time they were tears of relief that Gershkovich’s ordeal was over and our colleague was on his way home.

The three Americans landed at Joint Base Andrews that night to be greeted by their families, President Biden, and Vice President Kamala Harris—the end of a day that I suspect is indelibly marked on everyone who worked on the campaign.

Deterrence Is the Only Effective Antidote

There remain Americans detained in Russia. There are also local staff of US outlets jailed in their own countries simply for doing their job. Austin Tice, a freelancer who did work for McClatchy, the Washington Post, and CBS, has been held in Syria for twelve years and counting. Threats against journalists around the world are rising at an alarming rate.

Meanwhile, other regimes may look at Russia’s experience and conclude that taking a US journalist hostage leads to a significant reward from the world’s leading superpower.

Further, let’s not pretend that anyone likes these deals, given that they begin with a form of extortion. As one American held in Iran until September 2023 told me, “As soon as they take you, they win.” The captive’s government then moves mountains to try to level the score.

Yet on days like August 1, the values that underpin democracy and are the foundation of a free press triumph. The world’s most powerful government and its allies dedicated a massive effort to free sixteen individuals—including innocent Americans and political dissidents—who had been effectively held hostage by a hostile regime.

Few countries that are not democracies could point to such care for their ordinary citizens abroad, let alone noncitizens imprisoned for their political beliefs. And it is telling what Russia’s priority was for those it wanted back: intelligence operatives dispatched to undermine the West.

The US and its allies are now examining how to construct a form of mutual defense to discourage arbitrary detention by autocratic regimes. It is designed to remove the incentive for hostile governments to seize Westerners in the first place by signaling a unified and severe response. It is too early to say whether that will ever come to fruition.

In the meantime, news organizations must continue to assess and calibrate the risks their reporters face when operating in dangerous terrain. Perhaps they need to make more hard-nosed choices on whether it is necessary to deploy in person to countries that target journalists or whether that terrain can effectively be covered from outside, given advances in technology and communications.

And they could ensure that press freedom around the world—an issue so fundamental to their existence that it is often taken for granted—is a subject they cover as if their livelihoods and their liberty depended on it.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.