I have no other option than to start this column about Jim Romenesko with a litany of disclosures. Deep breath, here we go:

Romenesko has linked to my blog, Regret the Error, many times since it launched in 2004. My guess is he’s probably linked to me three to five times a year, maybe a bit more. (I’ve always tried to be judicious in the number of links I sent to him. I can only imagine what his inbox looks like.)

I’ve long been a fan of his blog. In fact it helped provide a measure of inspiration for me to want to launch my own media-focused blog. That said, he and I have never exchanged anything more than a few words by e-mail.

Also: I recently visited Poynter, the home of his blog for the past twelve years, to talk with them about how we can work together. Nothing has been formally agreed to but I expect there to be something to share publicly very soon. No, I’m not trying to be the next Romenesko.

I list all of the above because, of course, I’m writing about the events that led up to Romenesko’s resignation from Poynter yesterday. It began when Julie Moos, one of the people I’ve been speaking with at Poynter, put up a post explaining that, “Jim Romenesko’s posts exhibit a pattern of incomplete attribution.”

She learned this thanks to “the sharp eye of Erika Fry, an assistant editor at the Columbia Journalism Review.”

I am, of course, a columnist for CJR and have been for more than three years. I’ve never met or worked with Erika Fry. I have no knowledge about what she has been working on regarding Romenesko other than what was mentioned by Moos, on the CJR Twitter feed, and in this recent post by Justin Peters, who edits this column.

I think that covers most of the necessary disclosures, but in a sense this entire column is a disclosure.

So, the basic questions: Was it plagiarism? Or is what Romenesko did wrong?

Moos herself says Romenesko is not a plagiarist. She told 10,000 Words that, “I don’t characterize it as plagiarism, which usually involves an intent to deceive.”

I agree: Romenesko is scrupulous about always telling you where the information came from. Plagiarism involves an element of passing off another’s work as your own and not offering any credit. A plagiarist doesn’t want people to know where it came from. Romenesko is big on credit. He cites journalists’ names and their publications. He links back. It is at the very essence of what he does. He finds the good stuff and tells you how to get more if you want it.

Was it a mistake on his part to not put quotation marks around verbatim passages? Of course it was. That’s basic journalistic practice, and it matters how frequently this occurred.

Reuters’ Felix Salmon argues passionately that Romenesko did not need to put quotation marks around these passages, and that “If he’s violating the guidelines, then it’s the guidelines which are at fault, not Romenesko.”

My personal view is that just because you’re aggregating and curating it doesn’t excuse you from offering attribution in the form of quotes. I’m currently the editorial director of a Canadian online news organization that employs seven people we call “news curators.” Their job is to curate the best local news in their respective cities. Having them put verbatim passages in quotes is standard practice, and it serves everyone’s interests. Readers expect quotes and verbatim words to be in, well, quotes. So too do other news organizations. Those expectations inform how people consume our work.

Like everyone else, I’ll have to wait for the CJR piece to find out more specifics about this specific instance. Yesterday’s piece by Moos does not provide a list of examples, so I have no idea how often Romenesko mixed the words of others with his own. And, yes, I believe it’s important to know. We should have the full facts on the table.

For now, what’s striking to me about this whole affair is how me and a litany of other media folks instantly viewed this situation it in the same way. There is little, or no, dissention when it comes to the question of Romenesko’s intent and practices. (Peters touched on this in his post from today.)

At one point yesterday, Reuters’s Jack Shafer sent out a series of tweets noting that a large number of media critics—basically all of the well known ones in the US—had no complaints about Romenesko’s work when it came to attribution and linking. I was included on that list because I tweeted that Romenesko “has linked to me many times over the past seven years, and I never had an issue w/ attribution.” That’s been my personal experience. (Read all six Shafer tweets: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.)

So are all these media beat writers right, or are we gravitating towards the same point of view for other reasons? Dan Sinker called the whole thing “inside-baseball bullshittery”, and he’s right in the sense that this is so inside that it’s worth examining whether media people can be fair about it.

Look at all of the necessary disclosures at the top of this column, and it’s valid to wonder if I’m able to think about this clearly. Aside from my own situation, I can’t remember a time when I saw such a large group of grizzled media writers and critics line up on the same side.

The personal aspect is relevant here. As of now it seems that no press or media writer had an experience with Romenesko that led them to think he’d unfairly used their words. That’s important.

Personally, it was a strange experience to realize how I instantly didn’t assume any conscious wrongdoing on the part of Romenesko. This is not how I usually react to a situation like this. Usually, when a publication speaks of a failure of attribution, I’m pretty skeptical, if not downright incredulous.

I spoke to a journalism class in Chicago via Skype a few weeks back, and a student asked me about whether I thought people claiming to have committed accidental plagiarism were sincere. I said something to the effect that about 90 or 95 percent of claims of failure of attribution or accidental plagiarism are probably bullshit.

But yesterday? I almost without hesitation placed Romenesko in the 5 percent as soon as I read the story by Moos. I didn’t for a second think he had deliberately tried to make other people’s words seem like his own. As I watched my Twitter feed explode about the story by Moos, I saw a great many media critics and journalists felt the same way.

What needs to be recognized is that so many of us on the media beat have a long relationship with Romenesko, even though I doubt more than a couple of us have ever met him. (I recall during one recent conversation with Moos that I referred to Romenesko as “the unicorn of journalism,” the mythical beast of aggregation no one ever sees.)

Media critics and news junkies have been reading him for more than a decade. We admire the herculean work he does to get up early, post often, and tease out the most interesting details from a huge amount of reporting and commentary. We like his work and we respect him. We feel a connection. We trust him.

The fact that he almost never gives interviews, doesn’t show up on panels at conferences, and seems genuinely uninterested in glory or feeding his own ego is incredibly rare in this business.

What else? Oh right: he has the ability to send a shitload of traffic your way. That’s currency, power.

So, yes, we also want to be on his good side. We’ve benefitted from him over the years. I admit without hesitation that him linking to my site, even just a few times a year, has helped it establish credibility in the worlds of media criticism and journalism.

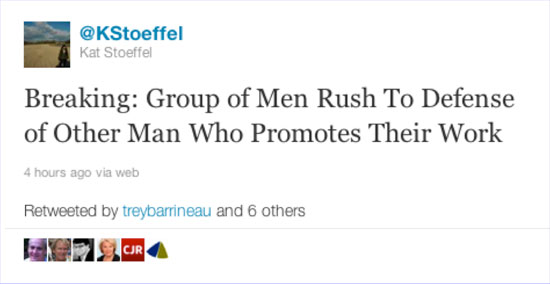

This tweet from New York Observer writer Kat Stoeffel summed up Romensko’s power and the unanimity of the response thus far:

Yes, it’s true: look at the list of media critics cited by Jack Shafer’s tweets. Almost all men. (Maybe all men, in fact.) See how it all seems like such a cozy little community of people standing up for one of their own?

We should remember this is often how people on the outside view the media. It may not be fair or true at a macro level, but the Romenesko affair is a notable case study.

I began this column listing a series of disclosures, and what’s followed is another expression of why you should be skeptical of what I and many other media critics think about the specifics of this. Even more so because the story that sparked this whole thing has yet to be published.

I don’t envy Erika Fry, the author of the forthcoming CJR piece. Lots of people seem to have already made up their minds, and they’ve really gone after Moos. I’m going to do my best to read what Fry has to say with a clear mind, knowing all the while that I’m so entwined and conflicted that I almost don’t trust myself.

Correction of the Week

“Quotations in a story about the Istrouma High School-Broadmoor High School football game that appeared in The Advocate on Saturday, Oct. 29, were wrongly attributed to Broadmoor coach Rusty Price. The reporter who wrote the story thought he was interviewing coach Price after the game. Because the interview subject was not Price, the reporter is unsure whom he spoke with.

“The Advocate regrets the error.” — The Advocate (Louisiana)

Craig Silverman is currently BuzzFeed's media editor, and formerly a fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism.