Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Terrorism relies on the spread of fear, so any publicity—from journalists or otherwise—threatens to play into its aims. The ability of terrorists to disseminate information and recruit has only gotten more powerful with the rise of social media. In the past month, the Tow Center for Digital Journalism has published three reports on how journalism should cover terrorism.

We’ve also worked to collect concrete guidelines for journalists confronted with a potentially terror-related breaking news incident—some of which come from a panel on September 22 at New America Foundation on Covering Terrorism: Civic Resilience in the Information Age. A few tips:

- Avoid adjectives like “chilling,” “terrifying,” and “existential,” said researcher J.M. Berger at the New America panel. Such words congratulate terrorists, he says. “Labels such as ‘lone wolf’ or ‘evil,’” writes Charlie Beckett in his white paper on best practices for journalists working on terrorism, “resonate but have little factual meaning.” Instead, they incite fear and appeal to the audience’s emotional response.

- “We are all driven by the desire to get a scoop, but these scoops are highly, highly perishable,” said Shane Harris, a correspondent at The Daily Beast, at the New America event.

“There’s a lot of pressure to find out what the motivation of the person behind the event is,” said CNN National Security Analyst Peter Bergen. He added it is the responsibility of the journalist and the government to make explicit that the story “is surely going to evolve.”

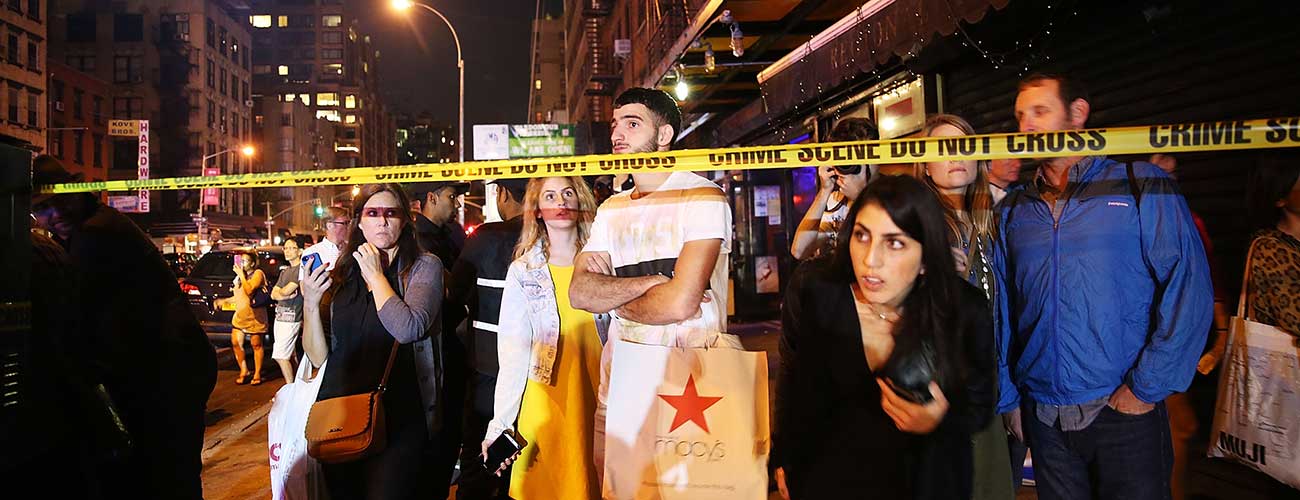

To take the Chelsea bombing as an example, Bergen noted that New York Mayor Bill de Blasio initially said the incident wasn’t related to terrorism, and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said there was no link to international terrorism. Those positions have since become debatable. Similarly, Bergen continues: “Government officials were saying, at least on background, there was probably a cell involved,” a statement that was later revised. “It’s not that they were wrong to say that,” he acknowledges, because that’s the logic of having four bombs in four different places. As they learned more, “they wanted to reassure the public and say there wasn’t a cell.” - While it is important to remain objective, journalists also must consider how details will be received in the context of current political rhetoric. When it came to Ahmad Rahami and the Chelsea bombings, Harris described being very careful with credible information that came in about Rahami coming to the US as the son of an asylum seeker: “In the political moment that we’re having right now where one candidate in particular is seizing on the … perceived threat of refugees, for us to report this was the son of a refugee would have ignited a whole political conversation.” Bergen noted that there has been a shift in recent years toward naming the perpetrator as little as possible and focusing instead on the victims. As Beckett writes: “Journalists need to reflect on whether they treat similar stories in different places proportionally, and whether they include diverse voices and informed comments.”

- Is there a story yet? CNN’s Peter Bergen says, “I was getting a lot of pressure on Sunday [the day after the Chelsea bombing] to write a story, and I said look, I can’t write a story because I don’t know who this person is.” When he learned the identity of Rahami, he looked for the analytical story to provide context for the motivation: “He’s not a foreigner, he’s not a refugee, he’s not a recent immigrant. You don’t need to get into the politics of this all. He’s an American citizen.” Bergen waited for more information to do any analysis.

- Don’t confuse terrorism with Islam, and make sure your coverage of Islam doesn’t only happen when there’s a terrorist incident. At the Excellence in Journalism 2016 conference September 18–20, a fantastic panel on “Covering Islam” encouraged journalists to get to know Muslim communities and not just turn to them when their communities are most vulnerable and hurting.

As Lawyer and writer Rafia Zakaria writes in her paper for the Tow Center, there has been a conflation, codified by US law, between terrorism and Islam, such that many people believe all terrorists are Muslim. The press needs to unpack these elisions and counter such assumptions through responsible coverage. Beckett similarly notes that “more constructive narratives that include empathy, resilience, and positive responses to terror should be created as part of the news coverage itself.” - Social media is a great reporting tool to find sources and eyewitnesses: Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn. But journalistic judgment must be used when speaking with such sources and publishing their photos or information. Groups such as First Draft are developing collaborative ways to verify eyewitness accounts.

- “Journalists are professional skeptics,” The Daily Beast’s Shane Harris reminds us. Journalists have to remember this mantra on a daily basis when assessing information that comes to them, they also have to be cautious about perpetuating a grand narrative. As Henry Wismayer writes in CJR: “By subscribing to the concept of ideological war—of them versus us—the Western press is precipitating the apocalyptic future the Islamic State has scripted.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.