Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The immigrant roundups in Charlotte began over the weekend of November 15. Nick de la Canal, a reporter for local public radio station WFAE, captured the first video and photo confirmation of the Customs and Border Protection presence in town, WFAE executive editor Ely Portillo said: “He was up early and plugged in with sources.” After that, Portillo said, “every single member of our newsroom team responded to the CBP surge into our city. That includes our reporters, our [show] hosts, and our digital team.” All day Saturday, Sunday, and Monday they provided continual updates via their various platforms about CBP operations, some of which were picked up by national outlets including NPR, ABC, Univision, and others.

WFAE, Charlotte’s public radio station, is still regaining its footing after losing 10 percent of its annual budget in the federal rescission of public media funding. Corporate underwriting is soft, Portillo explained, as longtime supporters are now leery of having their name associated with public broadcasting. But the community had stepped up, Portillo said, and, for the moment, audience revenue was allowing WFAE to continue to provide some of the most accessible—by virtue of being on the radio—local reporting in Charlotte and beyond.

During that time thousands of children missed school, small businesses closed, and families stayed home from church for fear of being arrested by CBP agents, regardless of whether they were citizens or had ever committed a crime. At the same time, community members mobilized to protect their neighbors, forming carpools to drive people safely around town, recording the activities of CBP, and picking up groceries to deliver to people too afraid to leave their homes.

Local news outlets all over the city covered the raids, which echoed those that had taken place in Los Angeles, Chicago, and elsewhere. Enlace Latino NC, a bilingual outlet serving Charlotte and beyond, posted articles online including “¿Cómo pagar la fianza de una persona detenida por ICE?” (How do I pay bail for a person detained by ICE?) and “¿Cómo puedo planificar el futuro de mis hijos si me detienen o me deportan?” (How can I plan for my children’s future if I am detained or deported?). They also fielded questions about misinformation that was circulating on social media and in private messaging apps, responding in real time (similar to the WhatsApp channel developed by BlockClub Chicago in response to the roundups there). And, because Enlace is already a trusted source of information for people in their communities, it also set up a Signal chat for people who wanted to submit information to the encrypted channel anonymously.

The value of local news during crisis

The immigrant roundups coincided with a research project the Tow Center has been conducting to map the local news and information landscape in Charlotte. We have identified sixty-five local news outlets, spanning from print newspapers to Substack-based newsletters to commercial radio. The most basic criterion for inclusion was the regular production of factual news meant for a public audience—an intentionally wide net. Thus we included sports-focused blogs, lifestyle and culture outlets, and faith-based publications. Because of this inclusivity, we created two additional variables to delineate more “traditional” journalism outlets: whether a provider acts as a watchdog on those in power, and whether it employs any staff who identify or are identified as journalists; thirty-two met both criteria (both lists will be available at localnewsdirectory.org). We’ve also analyzed the communications of hundreds of Charlotte-serving civil society organizations, which play a crucial role in the city’s information landscape.

We’ll unpack our many findings in subsequent posts; here we focus on the Spanish-language outlets serving Charlotte. Of those thirty-two local news providers that employ journalists and serve a watchdog role, nine serve Hispanic communities, relaying their news in Spanish (one, Enlace, also publishes in English). Of the nine, we analyzed one year’s worth of content from six: Enlace Latino NC, Hola News—Charlotte, La Noticia Charlotte, Progreso Hispano News, QuéPasa Charlotte, and WSOC Telemundo. We mapped their coverage areas (as well as those of several other outlets) and created a tool to analyze the topics they covered and to identify the communities they are serving and how.

Spanish-language news and information in Charlotte

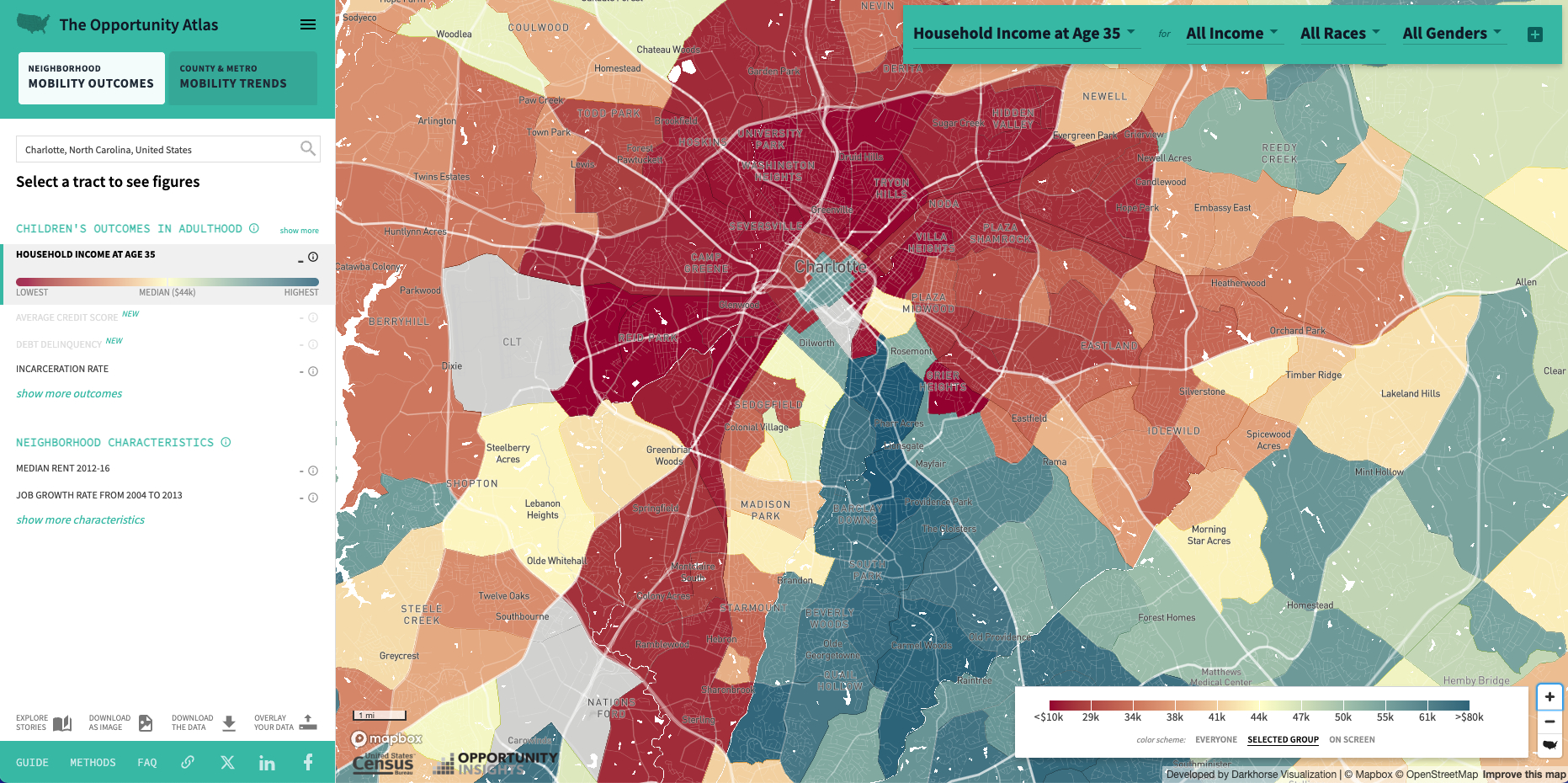

Charlotte is often visualized as a “wedge and crescent,” where the “wedge” indicates neighborhoods in the southern quarter of the city that have the highest household incomes, the highest average levels of education, and the highest percentages of white residents, while the surrounding “crescent” neighborhoods tend to score much lower on nearly every measure of both individual and community prosperity, while having the highest percentage of Black and Hispanic/Latinx residents. The image below shows this disparity on a map built by a research team that has been tracking inequality in Charlotte for more than two decades.

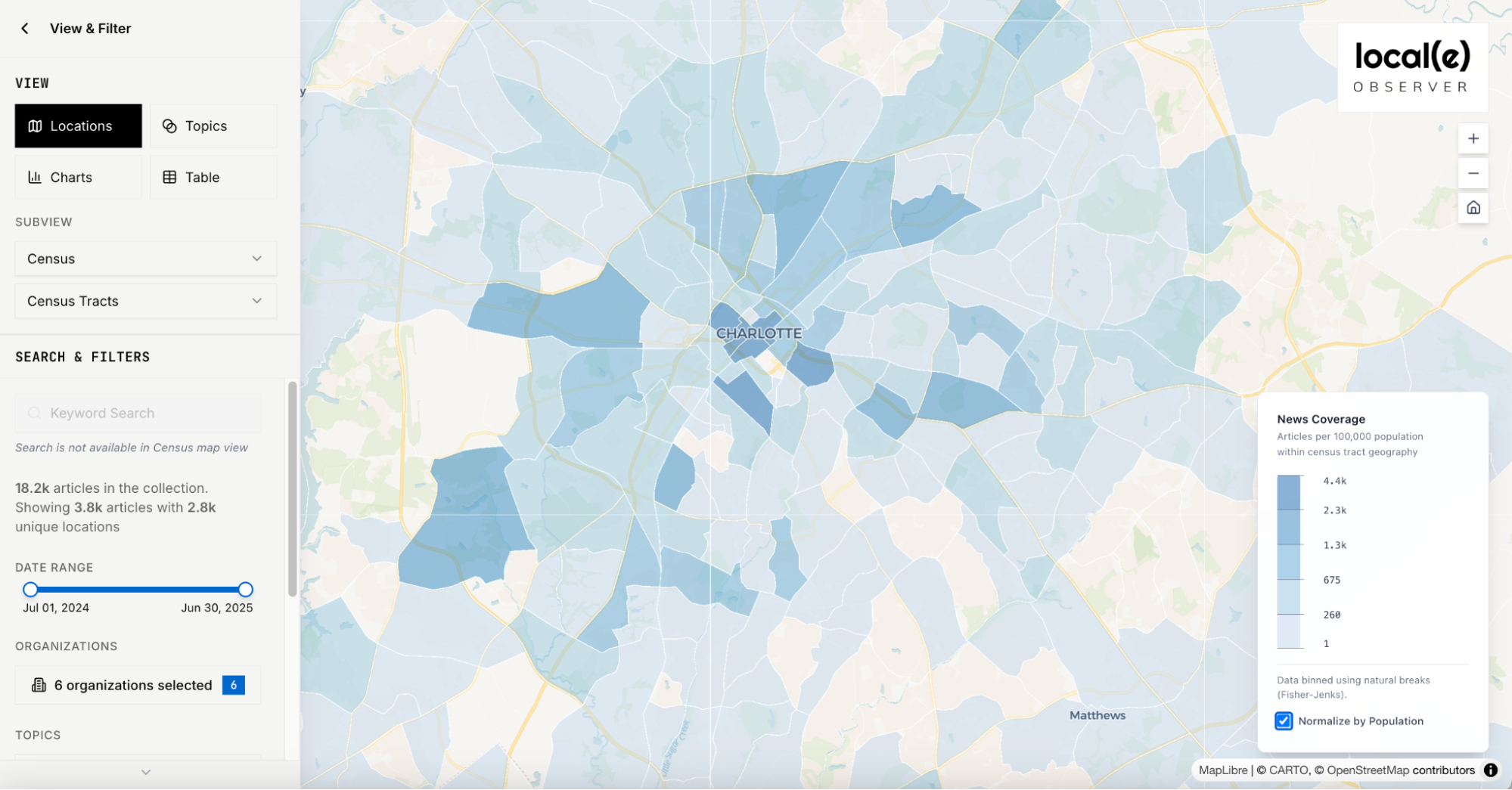

When we map the coverage areas of the Hispanic-serving Charlotte outlets by census tract, the crescent pattern appears (where the darker tract indicates a higher number of articles mentioning locations within that tract).

While our content collection period ended before the raids occurred, we gathered many articles about immigration, and found that local newsrooms were already preparing their audiences in the event that the roundups that were occurring elsewhere came to Charlotte. For example, Figure 3, below, shows Charlotte articles clustered by topic, using the tool our team developed. Within a cluster of stories about immigration, the tooltip highlights a QuéPasa Charlotte article from March 4, 2025, in Spanish, advising readers to know their rights if they are detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); Figure 4 is the English version of that article.

The subtitle mentions a free event, to be held on March 12. The event, the article explains, would be organized by the Carolina Migrant Network and take place in the Voice of Hope Church in Charlotte. Its goal was to inform everyone about their rights under the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights should they come into contact with authorities. Until recently, churches were one of the few remaining public spaces where vulnerable people felt safe. Notable here is the vital information-sharing performed by QuéPasa for its community, and the endorsement this article gives to the event—and, by extension, to the organization behind it.

This form of soft collaboration is becoming more and more common among local news outlets and civil society organizations. At the Monday-night panel, Tony Mecia, the founder and executive editor of the Charlotte Ledger, spoke about the ways that it partners with civil society organizations (CSOs) in times like this, while recognizing that these collaborations are somewhat new for the field: “It used to be we thought that [collaborating with CSOs] diminished impartiality, but now that’s totally changed,” Mecia said.

This kind of innovative practice is going to sustain local news, but only if we identify and talk about it. North Carolina journalism-support organization NC Local’s newsletter from the Friday of that week documented the critical role of local news during that time of shared trauma, and highlighted both the peril for local journalists as they covered the roundups and the camaraderie of the statewide journalism field.

On the Monday after the roundups went into full effect, there was a planned gathering organized by the NC Local News Lab Fund. It featured a short film that had been put together by the national fundraising group Press Forward, and a panel discussion after. The event was meant to bring together local journalists, philanthropists, civic organizations, city officials, and supporters of local news to reflect on the journalism landscape in Charlotte and emphasize the importance of local news to communities. Unfortunately, it could not have been better timed.

As we gathered, people were desperately seeking information on where the CBP agents were currently or were heading next. Many journalists who had planned to be at the event were out in the streets, some having been up reporting for more than twenty-four hours. As Portillo said, “journalists are a bit like firefighters—we run toward the smoke and sirens, not away.” Portillo and leaders from other local news organizations—Enlace, QCity Metro, the Ledger—described the efforts by their teams in real time.

As during the pandemic, and natural disasters, the critical role of local journalists and other civic information producers during the latest immigrant roundups was clear: Send trained journalists out to gather factual information, which is then transmitted to its audience on every available platform. Be in several places at once, and document the actions of those in power. And be a trusted messenger while bringing the community together. In other words, while the business model for local journalism may still be a work in progress, its value proposition is as solid as ever.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.