Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

There is no better illustration of the bewildering information ecosystem we now live in than debunking videos. These are the posts on YouTube, Facebook, TikTok, and so on with titles such as “Islam Debunked in 56 Seconds”; “Charlie Kirk BRUTALLY DEBUNKED, wrong about EVERYTHING”; and “The Great Big Pseudoarchaeology Debunk.” These posts are not inherently specious: they span the ideological spectrum and often deliver cogently explained information. But their purpose is not really to explain. Rather, they create the appearance of a great debate between two oppositional sides, when in reality their subjects are not so neatly divided, or no genuine divide exists at all.

Debunking videos are a perfect distillation of our online discourse: a debunk is a reaction to bunk tinged with moral outrage, and outraged reaction is, after all, the language of social media. It makes perfect bait for reaction chains in which every argument spawns a counterargument; every fact that is uttered prompts the appearance of a fact-checker in the replies; everyone is an expert, and every expert must prove their expertise by shouting over the noise of all the other charlatans pretending to be experts.

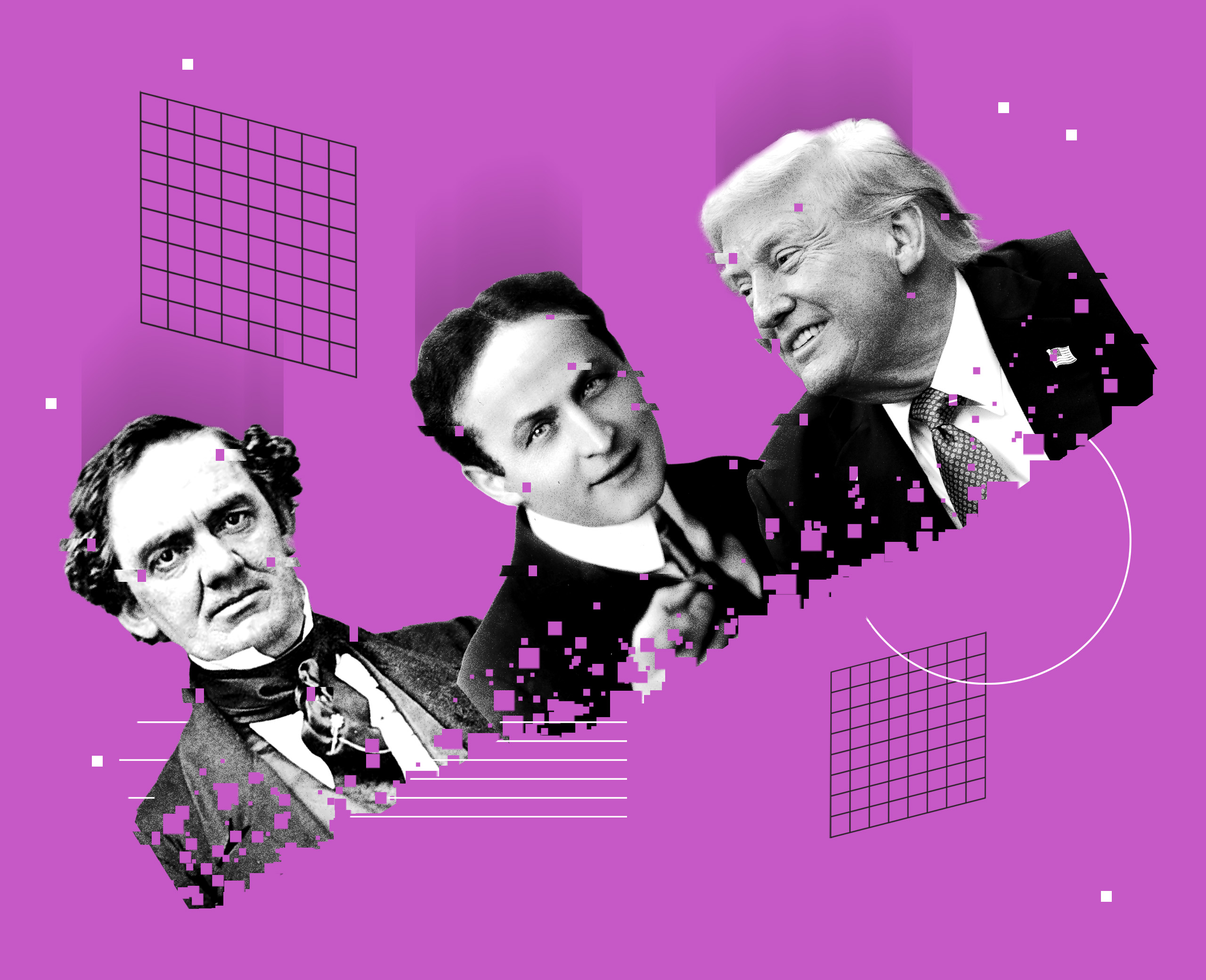

In Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News (2017), Kevin Young, an essayist and poet, looked at the rise of Donald Trump—that standout debunker of “fake news”—within the tradition of P.T. Barnum, the famous nineteenth-century sideshow promoter. Barnum knew that his audiences took “pleasure in hoaxing and being hoaxed,” Young writes. “What folks wanted was a show.” Barnum was not a mere con man or a fraudster, he was an entertainer who knew how to harness his audiences’ attention and convince them that a performance, however fake, “was worth it once you are already in the door.”

More bunking and debunking followed over the course of early-twentieth-century America. For a time, people held a fascination with the ghost-producing spectacles put on by spiritual mediums—and an equal appetite for the public unmasking of those same mediums as frauds. Harry Houdini was one such debunker, making it his mission, late in life, to put psychics out of business by exposing how their illusions worked. As the decades went on and concern about ghosts receded, skeptical investigators turned their attention to other popular paranormal phenomena: UFOs, Bigfoot, Satanic panic. At the start of the new millennium, Mythbusters, a hit Discovery show, took up the challenge of testing urban legends (swallowing Mentos with Diet Coke will make your stomach explode) via scientific experiment (it won’t). The point of all these efforts was that debunking could, by serving as a corrective to socially persuasive bunk, bring audiences closer to reality.

As a political figure, Trump has surpassed Barnum-style hoaxes by dismissing any pretense to authenticity. He regularly calls his opponents liars while making no effort to conceal his own lies; this works because whether people believe him or not doesn’t matter so much as whether he acts like he’s believed. The social media debunker who broadcasts his own, self-serving version of truth to millions of followers employs a similar sleight of hand. “The best way to commit a hoax now is to claim you’ve spotted one,” Young writes. Compared with straightforward deception, Trump has ushered in a “far more troubling mind-set—one in which the truth isn’t so much absent or contested as it doesn’t matter.”

This is the news environment we live in today. Americans trust journalism less than at any other point in history, and it’s easy to see why they don’t—because truth feels so impossible to access that it doesn’t seem to even matter what gets published. The future only looks murkier: A recent survey of American teenagers by the News Literacy Project found that a significant portion think journalism is “boring,” “biased,” and “fake.” Just 30 percent of teens think journalists confirm facts before publishing them; half of teens believe journalists make up quotes and other details; 60 percent think they take photos and videos out of context. The problem is partly a structural one. Where news was once a one-way street—a flawed but still intelligible system—now it comes from every direction at once: from legacy media, from self-described authorities on YouTube, from your Instagram friends, and from sandicheeks23 on Reddit. There is plenty that is good about this. But when everyone controls information, no one does—and what’s true and what’s false, what’s significant and what’s irrelevant, starts to look exactly the same.

Our online reality, which resembles something like tiny islands of real information submerged within a rising sea of slop, has more need of debunking than ever. But lately, debunking has taken on a strange new meaning. Debunking videos have become proving grounds not of fact, but of credibility. The debunker, rather than nudge his audience closer to the truth, directs them toward the version of it that he prefers. The result is that the debunk takes the place of the bunk—making the two virtually indistinguishable.

One recent example: a debunking aimed at Taylor Lorenz, the independent journalist behind User Mag, whose close reporting on the influencer economy is perhaps uniquely suited to stirring commotion online. In August, Lorenz published an article in Wired about a network of left-leaning political influencers who had accepted dark money without disclosing the payments on their channels. Lorenz’s reporting showed that in the wake of Trump’s second presidential win, Democrats were trying to build online influence using tactics borrowed from the right. But more notable than the story itself, perhaps, was the wave of reactions that immediately eclipsed it in tenor. After the article went up, Brian Taylor Cohen, a cofounder of the Democratic incubator program in question, posted a response on TikTok that is a master class in tables-turning and deflection. “Literally nothing in this statement is true,” he said in reference to Lorenz’s article. He did not refer to any specific falsities or provide corrections. Instead he focused on Lorenz’s character: She was a liar, and also a hypocrite, because she pretended to have a leftist point of view yet leveled her attack on Democratic influencers—the people on her own side. Who was she rooting for, anyway? She and Republicans both, Cohen said, “are desperate to tear the left apart.”

In many ways Cohen’s take was a typical response video. But as more responses proliferated from other creators named in Lorenz’s article, they took a common form: debunking. Aaron Parnas, who writes Substack’s top-ranked newsletter in the “news” category, posted on Instagram, “I need to take a minute and debunk some important misinformation.” Bunny Hedaya, a TikTok and Instagram influencer, said, “Let’s debunk literally everything she posted about me.” Soon came the responses to the responses. Ari Jacob—a social media strategist not named in the Wired article, who in 2021 sued Lorenz and the New York Times for defamation, in a case she later dropped—posted her own recap: “I break down the WIRED exposé, debunk media spin, and show receipts,” she said. These creators together hold a significant amount of credibility within the Democratic influencer space, and they leveraged that trust against Lorenz by labeling her reporting “misinformation,” framing their responses as corrections while sidestepping the article’s factual claims—and spurring Democratic allies to a defense of the cause.

One of the more stunning videos to come out of the reaction cycle was an eight-minute TikTok post purporting to deliver a treatise on media literacy. “There is no better example of the depths of the literacy and comprehension crisis that we are in than the responses that I have seen to this article,” an influencer named Sasha Whitney says in a tone so authoritative that I couldn’t help but nod along. Within a fog of manipulation, this video promised clarity. It would quiet the noise around Lorenz’s article and distill the conversation to its substance. Perfect. But then Whitney’s line of thought took a curious turn. She accused the headline of being “clickbait” that was “intentionally used” by Lorenz “in an obvious appeal to your emotion,” as if readers everywhere should beware their feelings. She defended the nondisclosure agreement the influencers signed to conceal the source of their funding as common in job contracts and “not nefarious.” The rest of the video is spent on tortured misreadings and wild accusations; it alternates between scolding Lorenz for being deceptive and her audience for being too illiterate to catch on. “Given the state of this country, and the fact that Republican and right-wing misinformation has done a number on the elections,” Whitney says, “one has to wonder what the entire point of this article was.”

That the “point” of Lorenz’s article was not to align its author with either the right or the left seems to have escaped these influencers seeking to “debunk” journalism that is unfavorable to them. It must be said that Lorenz, too, provokes and prolongs reactions to her own work. She followed up with several videos of her own that pull no punches, including a response to Sam Rosenholtz (account: GoodTrouble, followers: two million) titled “Debunking Journalism Fellowship Funding Myths” in which she says, “I’m actually shocked how ignorant and stupid these people are.”

All of these competing claims of debunking made it to a subreddit called Out of the Loop, where someone asked, “Since the release of this article, I’ve seen a lot of people criticize Lorenz for lying or not reporting accurately, and Lorenz has made several videos defending her work. But I feel like there have been a lot of angles to this and I can’t keep up.” The more than seven hundred comments to that post reveal a morass of confusion.

That confusion is not because the kids can’t read. It’s because anyone dropping in on this debate would have a genuinely difficult time figuring out what was going on. The result of piling readers with claims and counterclaims and tangential revelations and a mountain of receipts is not clarity, it’s obfuscation. Journalists know this, of course, which is why they routinely do things like select quotes from interviews and clip the most salient audio from hours-long speeches. Drawing a reader’s attention to the parts of the story that matter is a journalist’s most valuable skill.

The truth is that truth isn’t perched out there in the wilderness like a bird of paradise, waiting to be noticed. It emerges from the careful selection of facts and the winnowing away of competing claims. And it’s precisely this practice of selection and editing—the very process of journalistic truth-telling—that online right-wingers have increasingly called out as “dishonest” and “deceptive” as part of their ongoing campaign to sow distrust in legacy media channels and redirect that trust to their own channels.

In November, for example, after The Telegraph, a British newspaper, published documents suggesting that a BBC program had misleadingly edited a speech given by Trump in 2021, Karoline Leavitt, the White House press secretary, used the opening to discredit the BBC’s entire operation, calling the network “100% fake news.” (Focus on the edit was widely seen as part of a campaign to defund the BBC.) A similar obsession with edits and “altered” quotes emerged in the public sphere after Charlie Kirk was killed. Charged debates erupted online over controversial statements Kirk had made in his lifetime, with people sharing quotes of racist and bigoted speech from Kirk and others arguing that those quotes had been edited or purposefully taken out of context in order to smear him along with all conservatives. In that patronizing tone taken up by online debaters, each side alleged the other was ideologically brainwashed and in desperate need of media literacy.

When every piece of information online comes flanked by contradictory claims, who has the energy to sort real from fake? Just the other day, I opened the apps where most of my information comes from and was confronted with “news” in the form of a meme of Trump as the Hawk Tuah girl, the name of Laura Loomer’s dog (it’s “Loomer”), a list of Jennifer Lawrence’s most-wished-for cosmetic procedures, and several references to Olivia Nuzzi, RFK Jr.’s brain worm, and overgrown bamboo. I could sift through unsealed documents and google around to try to find out why Trump is now rumored to have serviced Bill Clinton, but it feels too complicated and exhausting to get to the bottom of it. Instead, I’ll let that nugget of information continue to live in my head unchallenged—at least until it gets debunked.

This piece is part of Journalism 2050, a project from the Columbia Journalism Review and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, with support from the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.