Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

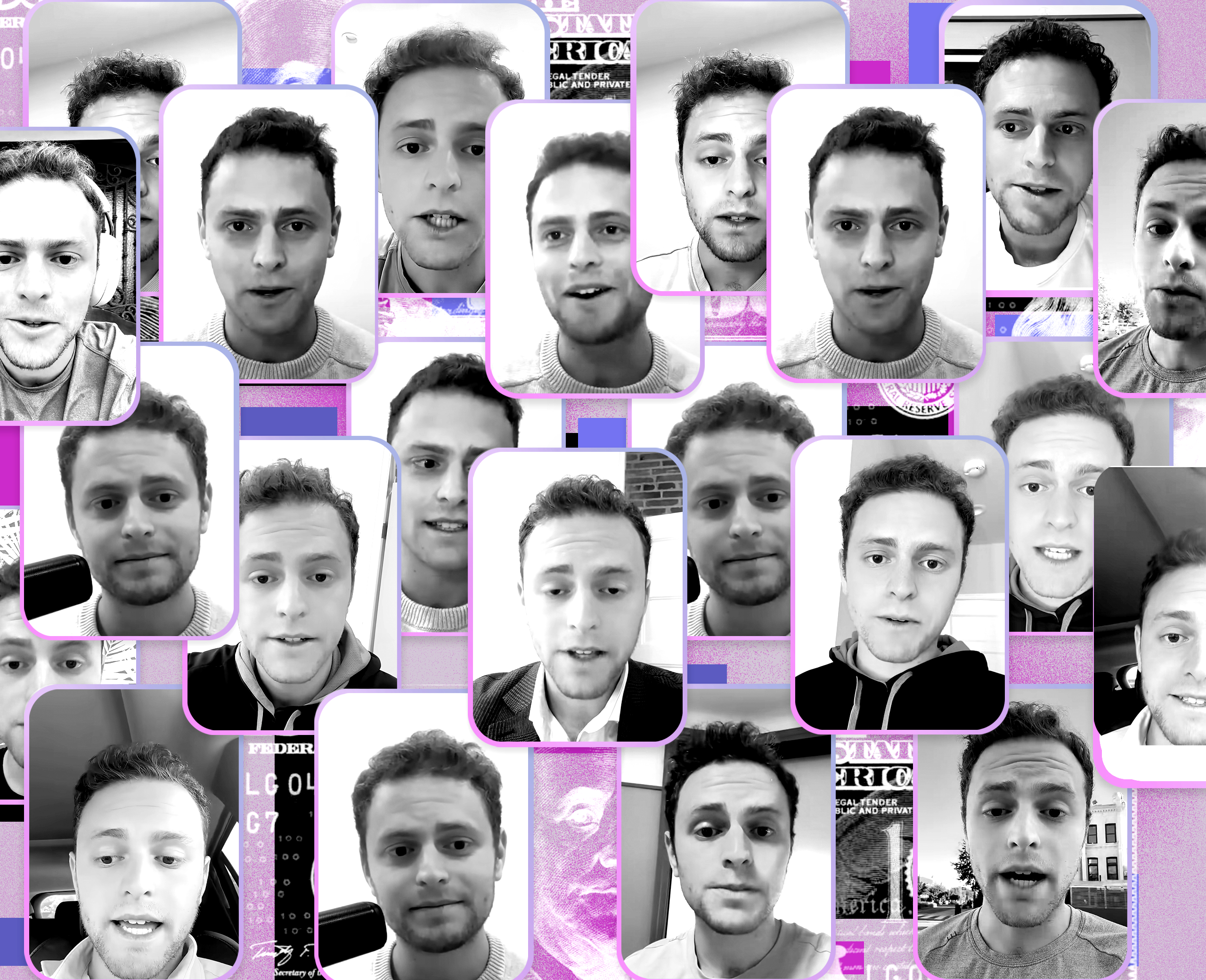

“I need to take a minute and debunk some important misinformation,” Aaron Parnas, a twenty-six-year-old content creator, said at the start of a minute-and-a-half, direct-to-camera video posted in late August to Instagram, TikTok, and X. Sporting a hoodie and recording in a nondescript gray corner of his apartment, in Washington, DC, Parnas was straightforward and earnest, miming the serious cadence of a TV newscaster. “Many of you have commented about this article that came out in ‘The Wired,’ asking if I have sold out, if I’ve taken money to push political talking points,” he said. He was referring to a Wired piece by Taylor Lorenz that described a program through which the Sixteen Thirty Fund, a liberal nonprofit, was funneling dark money to influencers—including, possibly, him. Parnas didn’t provide comment to Lorenz. Now the story, revealing details of the Chorus Creator Incubator Program, threatened his credibility as a crusading independent journalist.

“The point of it was to mentor smaller creators so that they can grow and that they can monetize their platforms,” Parnas told his followers. “This had nothing to do with politics, had nothing to do with political party, and had no control over the content I ever made.” Later that day, Parnas told me that he had received twenty-four thousand dollars from the Chorus program in early 2025. (He couldn’t send me his contract, he said.) The video focused on the substance of the Wired piece until the end, when Parnas turned to others in the media: “The people that are attacking me online are traditional journalists who are threatened by the work that I do.”

Coming from Parnas, that statement can almost feel like punching down. He has a knack for lightning-fast video and a social media reach that few on the “traditional” side of the industry will ever command as individuals: 4.3 million followers on TikTok, 1.4 million on Instagram, and another three hundred thousand on YouTube. (For comparison, the Washington Post, the first legacy outlet to embrace TikTok and do it well, has 1.9 million followers.) Most remarkable, Parnas has, in the past year, vaulted to the top of the Substack charts, with six hundred thousand subscribers to the Parnas Perspective, making it the number one bestselling newsletter in the site’s “news” category. Little of his output is behind a paywall, but Parnas sells subscriptions, which begin at $6.49 a month. He won’t say how much he earns there—and Substack, per its policies, wouldn’t tell me either. But in June, Substack reported that more than fifty of its most popular newsletters were bringing in at least a million dollars a year. If Parnas is doing half as well as, say, Matthew Yglesias—the former Vox blogger, who has said that he has eighteen thousand paying subscribers out of more than two hundred thousand readers, which delivers him a salary above a million dollars a year—he could be making bank. Last year, Parnas left his day job—working as a lawyer at Levi & Korsinsky, a securities class action firm—to pursue a career in news full-time.

As recently as early 2022, Parnas was just another Gen Zer with a TikTok, offering tours of his office and talking about his favorite pizza topping (pineapple) and premature hair loss. But Parnas—the son of Lev Parnas, who was embroiled in the Trump-Ukraine scandal—quickly developed a niche making videos about Russia’s invasion. Whether or not his audience connected the dots to his dad, they apparently found his portrayal of the events—and his personal ties, as a Ukrainian American—compelling. Parnas still makes videos about the war, citing reporting from news outlets. In a February 22 clip, for instance, he summarized Reuters on plans by the United States to block internet access in Ukraine in order to force a mineral rights deal. As Parnas dished for the camera, he also whitened his teeth. “Excuse my voice,” he told his followers, lisping. “It’s a little hard to speak. But the news doesn’t stop.”

Parnas records as many as a dozen videos a day, mostly from home, but sometimes from a dentist’s chair, an airplane bathroom, or in front of a weight rack at the gym. He’ll deliver White House updates and hold forth on other national happenings—but only if he can tell the entire story in under five minutes. “If I can’t, I won’t,” he said. He has told his followers, without a hint of self-deprecation, that together they are helping bring back the “Walter Cronkite era of news.”

On Substack, Parnas has benefited from the site’s push into video. He is not a prose stylist. His posts are full of platitudes about what it means to be a journalist, and have the clinical feel of AI, which Parnas told me he uses to proofread. (“The job of a free press is not to placate those in power. It is not to curry favor, nor to soften the truth so that it offends no one,” a recent post reads.) Rather, his superpowers are speed and generating a captive audience of resistance liberals. It’s why the nation’s top Democrats—Hakeem Jeffries, the House minority leader; Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader; and Gavin Newsom, the California governor—who have their pick of cable news shows, have begun regularly reaching out to Parnas. As a Democratic strategist whose client was recently on with Parnas told me, the value comes from getting in front of “highly motivated online givers, and he’s got those people who watch him.”

None of this has granted Parnas entry to the notoriously exclusionary DC media establishment. Parnas rankles some journalists for giving the appearance that he’s responsible for breaking the news that he relays. “Especially the cable networks, they hate this guy,” Pablo Manríquez, a reporter in Washington, told me. “They’re always talking about how Aaron Parnas is stealing their work and not giving them credit.” (Manríquez, for his part, said he doesn’t have a problem with Parnas, and has a Substack of his own.) Snapchat host Peter Hamby, one of the first big-name journalists to decamp for social media, wrote on X in April that news influencers, including Parnas, “literally just copy and paste reporting from working reporters and newsrooms.” If Parnas does share something original, it’s generally via one of his interviews. In early August, Pete Buttigieg clarified to Parnas controversial comments that he had once made about young transgender athletes. A week later, a clip of Schumer ping-ponged across X after he told Parnas “no fucking way” would he allow Trump to deploy National Guard troops to DC. Later that month, Sherrod Brown, the former senator from Ohio, gave Parnas the “Substack exclusive” on the launch of his comeback campaign.

Parnas has entered the journalism world at a time when trust in the legacy media has plummeted to historical lows. “He’s not controlled by a company that can tell him what to do and what not to do,” Don Lemon—the former CNN anchor, who now has a show on YouTube and a presence on TikTok—told me. “He’s carved out a way, in this new environment, to bring people information, and that’s extremely important.” It may be that Parnas has cultivated such confidence from his audience that they can forgive, or dismiss, the fact that he collaborates with a dark-money group. That’s part of his appeal: Parnas is writing his own rules. The rest of us just might not entirely know what they are.

If you scroll to the beginning of “aaronparnas1” on TikTok, you’ll find a video from early February 2022. Parnas, in a light-blue oxford, panned his office. The walls were greige and bare, except for his law degree, from George Washington University. He showed the typical stuff—computers, boxes of papers, a landline—next to which he kept a box of Hershey’s Kisses made exclusively for the Biden White House and given to him by a friend. “These remind me that there’s always something more than just law that I’m working for,” Parnas said. Then he solicited his followers for decorating ideas.

Parnas posted that video days before Russia invaded Ukraine. Several weeks after that, he uploaded footage of a pro-Ukraine demonstration outside the White House, showing throngs of people draped in blue-and-yellow flags. Many of his early videos on the war, which relayed firsthand stories of his extended family members in the country, were lost to an account (“aaronparnas6”) that Parnas told me TikTok had banned. (TikTok did not respond to my request for comment, though at the time, according to Vice, Russia was pressuring the company to block footage of the war.) Be that as it may, hundreds, if not thousands, of videos on Parnas’s backup account—which ultimately became his primary—show how he built a following with a relentless combination of news and lifestyle posts.

There’s an almost unbelievable irony to the fact that Parnas amassed his following by talking about the war in Ukraine. The elder Parnas was a central figure in Trump’s first impeachment, which focused on the president’s attempt to surface damaging information about Hunter Biden, concerning his link to a Ukrainian energy company called Burisma: Lev Parnas had worked in Ukraine for Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s onetime attorney, making connections that could help the Trump administration. Trump denied knowing Parnas, and was ultimately acquitted; Lev Parnas was never brought up on charges directly connected to the impeachment. But in 2022, the US attorney for the Southern District of New York indicted Lev Parnas for his role in a scheme to funnel foreign contributions to US candidates in order to gain political support for a cannabis operation. Parnas was convicted and sentenced to twenty months in prison for campaign finance offenses, wire fraud, and making false statements.

Parnas recalled attending GOP events with his father during the 2016 election and once meeting Trump in a photo line at a rally in Doral, Florida, about an hour from where he grew up, in Boca Raton. Parnas, the second oldest of seven siblings, told me that he was the first in his family to graduate from college, which was maybe underselling the accomplishment: In high school, he enrolled in an accelerated academic program through Florida Atlantic University that allowed him to begin college at fourteen. At eighteen, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in political science and criminal justice. He then went straight to law school. There, he had a “political awakening,” as he told Katie Couric on her podcast in May: “I just never really fit into the ‘MAGA’ circles,” he said. “I never talked like them. I never acted like them. I just didn’t enjoy being in those rooms. And so while I stood by my dad while he was in those circles, I just kind of kept quiet because I wanted to be a lawyer, right?” For three months in 2021, he served as a volunteer spokesperson for the Miami-Dade Democratic Party. In 2024, he told followers, he voted for Kamala Harris.

Lev Parnas is now out of prison—and on Substack as an anti-Trumper. (Aaron Parnas has been on Lev Parnas’s platform once, but Lev Parnas, to date, has not been on his son’s.) Last year, the elder Parnas was the subject of a documentary produced by Rachel Maddow, To Russia with Lev, which traces his life as a Soviet-born immigrant and South Florida hustler. I recently asked Aaron Parnas, who was not part of the film, what he thought of it, when we met up near the National Mall. “I mean, it was interesting,” he said. “Truth be told, I didn’t watch the whole thing. There’s a lot of trauma there from that time, and I try not to relive it if I don’t have to.” Parnas told Couric (who since the podcast interview has appeared with Parnas in a video on his Substack) something similar when she pressed him about what he may have witnessed regarding his father and Trump: “I have worked my hardest to kind of black it out, in a way, as a coping mechanism.”

While forging his law career, Parnas also acted as his father’s media consultant and spokesperson, helping Lev Parnas navigate the intense spotlight on Ukraine. “He would get an interview request and he would talk to me first,” he told me. His father was “a product of a very different and admirable environment,” he said. “He came over from Ukraine at a time of major instability. His dad died when he was four years old from a heart attack. His mom and grandma had to really raise him and his sister—single mom, first time in America, barely knew English. They had to scrape for money in New York and Detroit, and they made it by. But he also had to grow up a lot faster than he wanted.”

Parnas has been outspoken with his followers about the personal toll of his father’s legal troubles. “Overnight, I wasn’t Aaron anymore. I was ‘Lev Parnas’s son.’ My last name became a headline,” he said in a Substack video and post, The Story I Haven’t Fully Told Until Now. “Job offers I had worked years for disappeared. The legal community slammed doors in my face—not for what I had done, but because of my last name.” He added, “I share it because it explains why I approach journalism the way I do.”

Moments after arriving at Union Station, where National Guard troops from across the country have assembled to fortify the nation’s capital at the behest of the Trump administration, Parnas raised his phone to face-height and began recording. “I’m trying to educate people on what’s happening in DC,” he told me afterward. In one take, lasting around a minute, he described the scene. Then he posted the clip while continuing to chat with me.

Parnas, wearing a gray Lululemon top, black gym shorts, and black-and-white sneakers, looked like he had either just come from the gym or was about to sprint down the street. He spends two hours at the gym most days, he explained; it’s the one block of time he reserves during business hours for non-work. He wakes at 7:30am; by ten, he’s sent out his first video-newsletter of the day, via Substack. He then continues recording videos every thirty minutes or so, until about seven in the evening. “There is no such thing as work-life balance if you want to be at the top,” he said. “You always have to be on the clock.” We strolled out of Union Station and talked for a while; about an hour in, he showed me that the video he’d just posted had more than a hundred thousand views cross-platform. That sounded good. I asked Parnas if he was pleased. He shrugged. “It’s fine,” he said. “It’s nothing out-of-this-world amazing.”

Last January, Parnas married a former law school classmate, with whom he lives in Logan Circle, a trendy neighborhood not far from the White House. He makes time for her, he told me. “I will always talk to my family or friends on the phone, and that will be a priority,” he said. “That doesn’t mean that when I’m in the gym I won’t record, or when I’m watching TV with my wife I won’t step aside for a minute and record if I have to.” (His wife doesn’t appear in his recent videos and declined to comment through him.)

Parnas is expert at knowing what his audience responds to—and reinforcing their skepticism of corporate media with vows about his own objectivity and tenacity. Trump, as ever, is a go-to subject. “My reporting is not funded by billionaires or corporations—it’s powered by readers who care about truth,” he wrote to Substack subscribers in early September. Parnas said he stands by that statement, even in the wake of the Lorenz article. (“I don’t think that you can claim to be a truly independent journalist while taking money as part of a political-influence scheme that you don’t disclose to your audience,” Lorenz told me.) He doesn’t know the demographics of his Substack following, but in general, his reach stretches past Gen Z: he told me that, according to data provided by TikTok and Instagram, half of his audience on those platforms is over the age of forty. His most engaged followers are mostly in their thirties and forties. That seemed consistent with my awareness of him: Parnas will sometimes pop up in Facebook stories from Gen Xers and boomers I know who go to “No Kings” rallies on weekends. On TikTok, my algorithm won’t typically show me Parnas, but will surface memes that poke fun at the exaggerated urgency of his videos, which all begin with some variation of “We have breaking news.”

Outside Union Station, Parnas was spotted by a fan. “You keep us informed. You fight the good fight,” Adam, a forty-two-year-old from Texas, told him. Parnas is his go-to news source—along with V Spehar, another TikToker, whose shtick is delivering news updates from beneath a desk. “People can easily say he’s channeling one side or another, but what side one should really think of as the correct side is just based on fact,” Adam said. He no longer watches mainstream outlets. “I gave up on CNN, never watched Fox News, gave up on MSNBC,” whereas Parnas, he said, “is just trying to give you the news. No b.s.”

Back in April, when political journalists were schmoozing at the Washington Hilton for the annual White House Correspondents’ Dinner, Parnas was a thousand miles away, at his best friend’s wedding in Florida. Unlike the Democratic National Convention, which Parnas attended as one of two hundred credentialed influencers, the White House Correspondents’ Association, which charges member organizations in legacy media thousands of dollars for seats, was not about to grant content creators free or even paid access. Parnas doesn’t see the logic in that. “Theoretically, I think new media should be invited,” he said. “I don’t care that I wasn’t invited, right? But like, me or anyone else in the space—I feel like you have a roomful of five thousand people every year, you could have two seats for new media.” I wondered about the conflict with his friend’s wedding. “I would have made it work,” he said.

Parnas lands major interviews, but does so without credentialed press access to the US Capitol or the White House. This year, the Trump administration made space in the briefing room for new-media figures who aren’t members of the WHCA—but in general, seats are doled out through a process determined by journalists. It’s a clubhouse. That dynamic has been his “biggest growing pain,” Parnas told me. “Even to this day, I mean, my platform is looked down upon by institutions, like the mainstream.” He continued, “A lot of people are like, ‘I can’t believe you’re not on CNN every night, or you’re not on Fox or MSNBC.’ And I’m like, well, they don’t reach out. They’ve never reached out. And I would love to work with them. I think we’re in a place where there should be more collaboration with content creators or social media–first journalists versus the mainstream.”

Some aren’t sure what to make of him. Is he a journalist? “It’s yes and no, right?” said Greg Landsman, a House Democrat from Ohio who recently sought an interview with Parnas on YouTube. “He’s giving people an opportunity to come on and have a conversation. Certainly, he asks good questions. You get into the substance of something that you can’t get with TV.” Hamby, the Snapchat host who accused Parnas of “copy-and-paste reporting,” told me that Parnas poses a problem for journalism that legacy newsrooms created: “They hold back partnering or letting their journalists do new kinds of journalism,” he said, “and then you’ve got people who aren’t beholden to legacy norms, values, journalistic principles, who rush into these places and build a huge following.”

That scenario was highlighted by the Lorenz article in Wired: news influencers can draw their own ethical blueprints. Speaking with me, Parnas disputed the idea that he was secretly part of a paid system to push Democratic talking points in order to better compete against those who do the same on the right. His coverage, he insisted, has been above reproach, even if he accepted money without telling his followers. The arrangement he has with the Chorus Creator Incubator Program doesn’t amount to a partnership, in his view; he compared it to side gigs he’s had tutoring for the bar and grading essays. “My audience has been like, ‘Yeah, this is b.s.,’” he told me. “Some have had questions, and I’ve answered all their questions, so it’s been kind of fine.”

Parnas believes a journalist is “anyone who educates others on the news,” and that he is squarely in that category. “They call me a content creator, but that’s mainly coming from people who are part of the institution. Every platform, to me, is just a different way of sharing news. Jake Tapper and Abby Phillip and all these people—yes, they’re journalists. But to me they’re content creators and influencers, they’re just on TV. Writers are content creators if you’re creating content for print or radio.”

In the coming months, Parnas will add a podcast to his repertoire, and he would eventually like to have his own streaming show or cable news hour, he told me, “if it’s done the right way.” Then he hopes to retire and focus on pro bono legal-defense work. “I don’t envision my career to be a fifty-year journalism career. I know that at some point it’s going to run out,” he said. “People are going to find the next thing to watch, the next big platform. And when they do, I’ll know it’s my time.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.