Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On a Thursday morning during last fall’s impeachment hearings, Geoff Bennett, an NBC White House correspondent, approached then-Ambassador Gordon Sondland as he was walking toward the Capitol. Robert Luskin, the ambassador’s attorney, intervened by shoving aside Bennett’s mic and then trying to block him from questioning his client. Bennett wasn’t fazed. He told Luskin, “As a respected attorney, I am sure you understand how the free press works, sir!” and then walked unencumbered to pose his questions to Sondland.

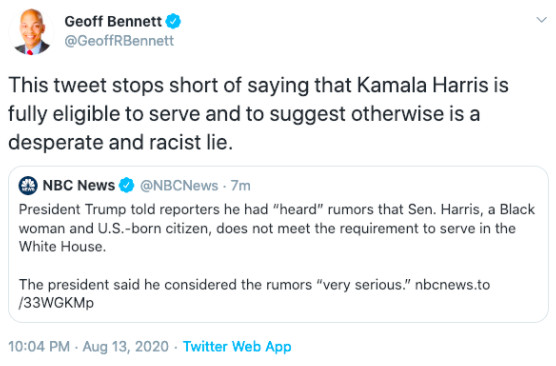

Bennett is not afraid to push back. And we saw that intensity again late Thursday night, shortly after the official Twitter account for NBC News posted this:

President Trump told reporters he had “heard” rumors that Sen. Harris, a Black woman and U.S.-born citizen, does not meet the requirement to serve in the White House. The president said he considered the rumors “very serious.”

Within minutes, Bennett went public, castigating his own newsroom with a quote-tweet to his 100,000 or so followers: “This tweet stops short of saying Kamala Harris is fully eligible to serve and to suggest otherwise is a desperate and racist lie.”

Minutes later, NBC deleted its tweet and posted a new one, with a tone much closer to Bennett’s: “Sen. Harris’ eligibility to be president is not in doubt, despite racist birtherism suggestions that were echoed by the president Thursday.” Then, to make sure everyone got the message, the network pinned that new tweet to the top of its feed—and left it there for several days so it would be the first thing that NBC News’s 7.7 million followers would see.

Journalists pride themselves on speaking truth to power. Increasingly, that truth is directed toward their own editors and colleagues, and in the most public ways possible. For certain journalists—particularly those with stature, and those fortunate to work for responsive management—this route gets results. It can also be less risky than the traditional, private “boss, can I talk to you” discussion. By going public, reporters can generate a groundswell of support that will insulate them from managerial retribution.

But does it work for everyone? And should it? While the feedback can be valuable, the consequences can be severe. That is especially true now, when newsroom jobs are precarious, and when journalists can be viciously targeted by anonymous trolls.

How often, and under what circumstances, should journalists openly criticize their organizations or support colleagues who’ve been disciplined?

The genesis of the Bennett incident was a column in Newsweek (which I won’t link to) that presented specious legal arguments to raise doubts about whether Sen. Harris fulfills the constitutional requirements to be president. It was hard to find a legal scholar who would defend the op-ed, but the theory was catnip to Donald Trump, who launched his candidacy years ago by shilling phony, racist conspiracies around Barack Obama’s birth certificate. Asked about Harris’s eligibility at a press briefing last Thursday, the president pumped his bellows and fanned the embers: “I heard it today that she doesn’t meet the requirements. And, by the way, the lawyer that wrote that piece is a very highly qualified, very talented lawyer. I have no idea if that’s right. I would have assumed the Democrats would have checked that out before she gets chosen to run for vice president.”

NBC News’ tweet on the incident was, in the most literal sense, “accurate.” That is, Trump was quoted correctly, and no words were misspelled. But it failed to convey to readers that Newsweek’s column was deeply flawed, or that Trump’s response was designed to instill doubt in voters’ minds.

Bennett isn’t an MSNBC-style partisan. He is an experienced journalist, with years at ABC News, NY1 and NPR before joining NBC in 2017. He also has hosted C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, the pinnacle of fair-minded broadcast news.

Nor was Bennett the only journalist to go public with concerns. After Trump’s press conference, NPR led its story much the way NBC had framed its tweet: “President Trump stoked a controversial theory being promoted by supporters—and his campaign—that Sen. Kamala Harris of California is not eligible for the vice presidency.” Lulu Garcia-Navarro, the host of NPR’s Weekend Edition Sunday who has won Peabody and duPont awards, told her 78,500 Twitter followers that ”this language does our audience a grave disservice. It’s not a ‘theory’. It’s a lie.” NPR changed the phrase “controversial theory” to “an untrue conspiracy theory” and went on to acknowledge on Twitter that its language hadn’t been “clear enough that suggestions Sen. Harris isn’t eligible are lies.” Minutes later, Garcia-Navarro tweeted, “This is what a credible news organization does. I am proud to work at NPR.”

And even some Newsweek journalists — including a top correspondent and a senior editor — went public with their disgust.

THE MEDIA TODAY: Information overload on night one of the Democrats’ virtual convention

Grumbling about your employer or your colleagues is hardly new in journalism. For many reporters, it’s both an occupational hazard and a nontaxable perk of the job. But in this COVID-19 era, when newsrooms are closing and atomized journalists are working out of their bedrooms, it’s more cumbersome to register your displeasure. And it’s hard to beat the gratification that comes from changing your newsroom’s policy in a public way.

“Criticism often goes underground (whisper networks, back channels) until a moment presents itself, and what was shared privately is broadcast publicly,” says Jill Geisler, a Loyola University faculty member who studies newsroom management and has written for CJR. “It happened in 2017 with media’s #MeToo scandals and again right now as #BlackLivesMatter opened new opportunity for outspokenness.”

But it doesn’t always go smoothly, particularly for journalists who have less experience or who work for smaller news organizations. Last May, as protests over the George Floyd killing heated up, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter Alexis Johnson posted a satirical tweet about a litter-filled parking lot, noting it was from a country-music concert. Bosses told Johnson, who is Black, that she could no longer cover the protests; they did the same to another Black staffer, photojournalist Michael Santiago, who had retweeted Johnson’s post and publicly supported her. Santiago left the paper; Johnson filed a lawsuit.

How often, and under what circumstances, should journalists openly criticize their organizations or support colleagues who’ve been disciplined? And will Twitter-fueled critiques stifle the kind of counterintuitive reporting, or untraditional approaches, that we expect journalists to tackle? As Geisler told me, “Public criticism can easily translate into bullying or scapegoating, the very thing that causes people to leave organizations. We don’t want that.”

Bennett and Garcia-Navarro fought a good fight here. They drew attention to mistakes that needed to be fixed quickly and transparently. Using their considerable experience and hard-earned credibility, their actions might also spur more systemic change in their news organizations.

But it’s possible to envision scenarios when Twitter critiques go awry, particularly when journalists get unfairly targeted, or when they turn their concerns into nasty, public battles that seek retribution more than justice. We might not always find the consequences to be as helpful or constructive.

I’m not 100% sure what the right policy is here. I am quite sure I’d benefit from your thoughts, so feel free to email me, at bgrueskin@columbia.edu.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.