Journalists who write about the new basketball arena rising in Brooklyn, scheduled to house the basketball Nets in 2012, frequently invoke the borough’s last major league team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, who left in 1957 for Los Angeles. They sometimes cite a seeming spiritual link: the Barclays Center arena is said to be located exactly where a successor to Ebbets Field could have emerged.”

A half-century earlier, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley had hoped to build a new home for his team on the same site,” writes Zack O’Malley Greenburg in Empire State of Mind: How Jay-Z Went From Street Corner to Corner Office, officially published March 17. (Jay-Z’s an investor in the Nets, hence a chapter on the Atlantic Yards project.) The Ebbets Field connection has been brought up by Mayor Mike Bloomberg, cited by a journalism professor and author on a book on the Dodgers, and even entered an ongoing exhibit at the Brooklyn Historical Society.

The problem? It’s a myth. The stadium would have been located across a wide avenue. While the myth has appeared in multiple media outlets, I believe that The New York Times, which many researchers treat as a reliable source, bears significant responsibility.

The error has appeared at least five times in the Times. For example, in a January 16, 2004 article headlined Yo, Dodgers? No Way! Brooklyn Is Betting on the Nets for Revival, the Times reported:

Coincidentally, the Nets would be based at the same site that Walter O’Malley wanted as a new home for the Dodgers before moving the team to California.

That article was cited as a source for the “same site” claim in Michael D’Antonio’s 2009 book, Forever Blue: The True Story of Walter O’Malley, Baseball’s Most Controversial Owner, and the Dodgers of Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

Developer Forest City Ratner has fueled the Dodgers-Nets connection by suggesting the arena would be built in the “same area” that O’Malley sought. But the press has taken it further. Consider a July 1, 2004 Times editorial, which referenced “the dream of giving back to Brooklyn some of the luster it lost when Robert Moses killed Walter O’Malley’s vision of building a domed stadium for the Dodgers at the same site nearly 50 years ago.” Or a November 13, 2005 Times op-ed by a former Brooklyn borough historian, which said that the Nets stadium would sit “on the very site that was denied the Brooklyn Dodgers 50 years ago.”

Why does the “same site” myth matter? It feeds a hunger for narrative, giving reporters a too-cute hook that distracts them from the hardball politics behind the arena project. Thus, it downplays the displacement of homes and businesses—thanks, in part, to a highly controversial use of eminent domain—from the arena site ultimately achieved by Forest City.

The Times has known of the error at least as far back as December 2007, when it had to correct an online article. I then wrote a letter listing mistakes in articles, an op-ed, and an editorial, explaining that an error-laden clip file could fuel further corrections.

Senior editor for standards Greg Brock, with whom I’ve exchanged periodic and sometimes contentious correspondence regarding the newspaper’s Atlantic Yards coverage, responded promptly. (I’ve been writing a watchdog blog about the Atlantic Yards project for more than five years, and my initial impetus was as a media critic.)

Brock explained that, while he would “ask our researchers to attach a note to each of the 2004 articles that will say that this is site is across the street,” he would not run a print correction for the mistake. “There is a limit to how many old articles we can correct in print,” he wrote.

As I responded, that seems to violate the newspaper’s Stylebook, which states:

Because its voice is loud and far-reaching, The Times recognizes an ethical responsibility to correct all its factual errors, large and small (even misspellings of names), promptly and in a prominent reserved space in the paper.

Moreover, the note in the archives affects only in-house access. And, I suggested, if there must be triage regarding the number of “old articles” the Times corrects in print, such corrections should be prioritized for articles connected to ongoing controversies, such as Atlantic Yards.

“We do in fact correct older articles from time to time. But it’s a case-by-case call, not a blanket rule,” Brock responded. “The best way to get an article corrected is to report the error at the time it occurs.”

But the real-world consequence of the Times’s policy is clear, given the error in D’Antonio’s book and, more likely than not, in Greenburg’s book (which doesn’t cite a source for the error).

Maybe the Times doesn’t want too much attention paid to its error-plagued coverage of the Atlantic Yards project, which is being built by the same developer who partnered with the New York Times Company to build the Times Tower in midtown Manhattan. (I’ve argued that the business relationship does not mean the Times is in the tank, but should obligate the newspaper to be exacting in its coverage.)

In 2006, the Times appended a mega-correction (which I’d pushed for) to various articles erroneously locating the Atlantic Yards project in downtown Brooklyn rather than nearby—another shading that favored the developer’s line.

Perhaps a second mega-correction would not have sit well.

The details

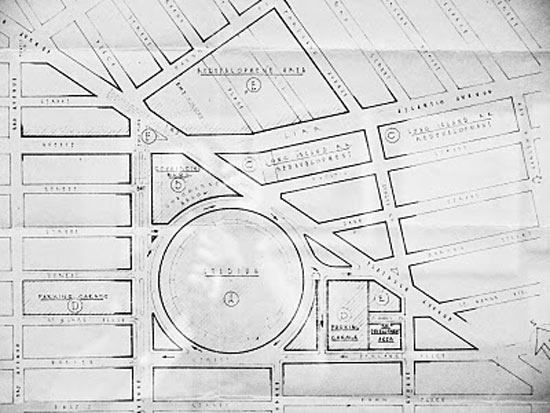

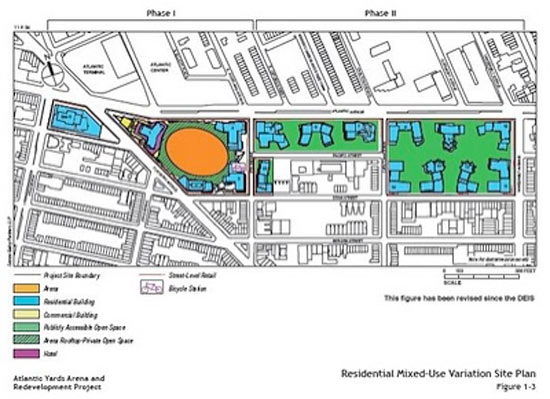

For those wanting to understand the ”same site” error, consider the outline of the Atlantic Yards project as proposed, with the arena footprint below broad, divided Atlantic Avenue, extending through Pacific Street south to Dean Street.

The railyard, known as the Vanderbilt Yard, is located between Atlantic Avenue and the adjacent southern block, Pacific Street; the railyard functions have now been moved east of the arena block; no towers have been built yet.

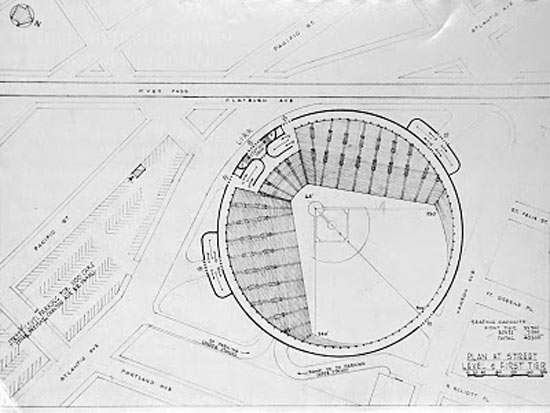

For O’Malley, part of the Vanderbilt Yard would have served as a parking area for the stadium, but he didn’t seek the block below the railyard, which contained residences and businesses (and vacant buildings/lots) since displaced on Pacific and Dean streets. The stadium would have sat north of Atlantic Avenue, extending to Hanson Place, occupying an area now home to two shopping malls. In a rendering below of the stadium plan, Atlantic Avenue would have swerved somewhat to the south and Flatbush Avenue would have required an overpass.

(Note that the graphic below is rotated more than 90 degrees, with an arrow at upper left pointing north. Photos by Jonathan Barkey of renderings at the Brooklyn Historical Society exhibit.)

Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, by contrast, recommended a site to the southwest of the railyard, thus below both the property O’Malley sought as well as the arena site achieved by Ratner.