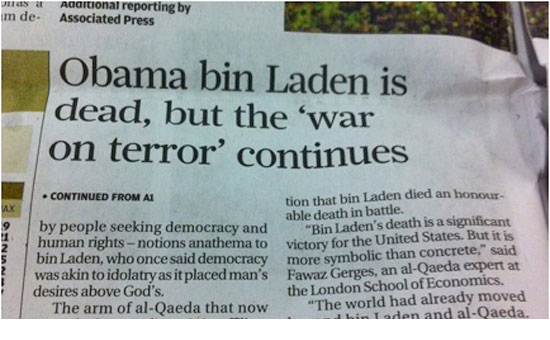

Of all the mistaken headlines, verbal gaffes, and erroneous tweets that resulted from the Sunday announcement that Osama Bin Laden had been killed, this tour de force of Obama/Osama confusion defeats all comers:

I take special pride in the fact that the offending anchor is a fellow Canadian. (She works for Global TV.) It also goes to show that the Obama/Osama error—I’ve collected the best/worst here—is an international phenomenon.

Yes, U.S. media dominated the mistaken news. To name but a few examples, Geraldo Rivera said on air that, “Obama is dead, I don’t care … what am I saying?”, NPR’s website declared, “Obama Bin Laden Is Dead, Officials Say”, and the website for ABC World News with Diane Sawyer reported that, “Sources Tell ABC News’ Jon Karl That Obama Will Be Buried At Sea.”

But you also had this headline from British broadcaster Sky News: “Reaction: World Leaders Hail Obama’s Death.” From the BBC, “Obama Dead.” From Canada to England to India and beyond, this was a mistake that cut across geographic barriers. (For a look at other errors made in the wake of Sunday’s news, see here and here.)

Obama/Osama was entrenched in the collective consciousness long before Obama went on live TV to say Osama was dead. The slip predates Sunday’s news by several years. Just watch this 2005 speech from the late Sen. Edward Kennedy in which he makes the mistake. The error was so prevalent in 2007 that I named it a Trend of Note in my year-end roundup.

This all inspires a very simple question: Why does it keep happening?

On the surface it’s an understandable slip. Both words are names; they are separated by just one letter; and the words are also often used in close proximity. Apart from that, one man was enemy number one of the country led by the other. Those are the obvious factors at play, but there are other more important causes for why journalists and others make this mistake—and these causes can help us understand and avoid similar errors.

The first thing to recognize is this slip almost always involves people saying Obama when they mean Osama. It’s rarely the other way around. There’s an important reason for this, according to Michael Erard, author of Um…: Slips, Stumbles, and Verbal Blunders, and What They Mean.

“What is happening in that specific case … is that the speaker has anticipated the ‘b’ of Bin laden and moved it up to replace the ‘s’ in Osama,” he told me. “That is an anticipation error, where there is a string of sounds and the person basically jumps ahead in the string and selects one sound too soon and inserts it.”

Erard said people are even more likely to make this error because the name “Osama Bin Laden” is stored in our brains as one chunk, rather than as three unique items. This makes it more likely we’ll skip ahead to the “b” in Bin Laden without paying close attention to the first word in the chunk (Osama). This is true even if you are only planning to say “Osama.”

“Even if they are not intending to produce Osama’s full name, they are rehearsing it sub-vocally so they are still looping the whole name in their brains,” Erard said.

Had his name been Osama Tin Laden, we likely would have seen a lot fewer Obama/Osama mixups. The fact that the first letter of the second word of Osama’s name is the same letter that changes Osama to Obama is an unfortunate coincidence.

That’s not the only factor at play with Obama/Osama errors.

When it comes to slips of the tongue, we are more likely to make an error using a real word. “Lexical bias is the way in which the slips tend to produce structured words, real words, words that fit the language,” Erard said.

So if you’re going to mess up Osama, there’s a good chance you’ll do it with a real (and similar) word.

Then there’s the “frequency effect,” which relates to how often a word is used.

“We say Obama a heck of a lot more than Osama, and so in terms of the network in which these words stored in our brains, Obama is activated more,” Erard said.

Though his points appear to primarily relate to speech, Erard said these factors also apply to writing. With the situation that unfolded Sunday night, there was the added factor of rushing to get words on screen or online as soon as possible.

“You don’t have the time, or as much time, to see or to attend to the potential error,” he said. A touch typist, Erard also noted the keyboard pattern for Obama/Osama is similar enough that it’s unlikely for someone to “feel” they’ve made a mistake.

Stacked together, there is an almost comical abundance of factors that make an Obama/Osama mistake likely. Perhaps that’s of consolation to the many journalists who fell victim to it this week. It’s also a valuable caution as there will be many occasions in the future when the two names feature in the same conversation or piece of reporting. Just ask the South China Morning Post:

Correction of the Week

“A timeline in the main news section Monday incorrectly stated how many siblings Osama bin Laden had. He was one of 54 children of a Saudi construction magnate.

Also, a story in some editions Monday on Page 2 about Osama bin Laden’s life said bin Laden died in the lawless badlands of Pakistan along the Afghanistan border. Bin Laden was killed in a house in Abbottabad, north of Islamabad. The story also repeated a paragraph that had some garbled sentences.” – Chicago Tribune