The New York Times is, more than any other single publication, the nation’s arbiter of erudition, prosperity, and success. So what better tool to gauge our collective sense of who and what matters, and how that has changed through the years, than to analyze the newspaper’s obit section? What does it take to merit an obit in the Times?

Earlier this year, I deployed 24 undergraduate students from the University of Michigan, where I was teaching as a visiting professor, to try to answer this question. The students scoured every obit published during the month of February, from 1942 through 2012, for the following information: place of death; birthplace; where s/he lived; gender; marital status; occupation; college attended; professional achievements; family lineage; parents’ occupations/achievements; spouse’s/children’s occupations/achievements; survivors; military service; association memberships; and sexual orientation. We also noted, if apparent, the deceased’s race and religion.

Our project was by no means scientific, but the results were nonetheless revealing:

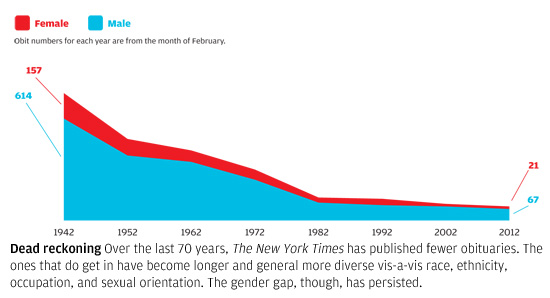

• In the 1940s and ’50s, the paper ran many more obits than it does today; some were but a single paragraph.

• Prior to 1960, cause of death was not always included; today, it usually is. In our survey, aids was first listed as a cause of death in 1992.

• Where the dead were educated has remained relatively constant: The Ivy League reigns supreme.

• The obits have always been male-heavy. In 1972, a typical female obit was two paragraphs, and spoke not of the deceased’s accomplishments but of those of her husband and sons.

• Starting in the 1990s, the obits became more diverse, racially and ethnically, but also in terms of people who had distinguished themselves in occupations other than business or politics—attorneys, artists, scientists, athletes, and actors.

But how does the Times decide whose contributions to society are worth noting? A colleague and friend of mine, Hanno Hardt, died October 11, 2011. Hardt was an internationally known scholar of communication, the author of nine influential books and scores of articles. Hardt coined the word “newsworker,” preferring it to “journalist,” since he fervently believed that reporters in their essence were not so different from fabric workers who are paid by the piece. Any communications scholar in the world likely has heard of Hardt. There also was enough color about Hardt to make for a classic Times obit. He called himself a neo-Marxist and drove a snazzy red BMW convertible; he bore such an uncanny physical resemblance to the writer Kurt Vonnegut that the two were occasionally confused.

However, Hardt was a professor at the University of Iowa—not the Ivy League. Still, I thought, it was worth a try. The day Hardt died, I contacted the Times with a brief note of his significance. After several days, I heard nothing back. I sent another email, and again got nothing. Hardt hadn’t made the cut.

What if Hardt had taught at Columbia or Harvard? What if he’d been married to a Hungarian countess or Lauren Hutton? Might that have changed the calculus? That’s the ineffable quality of obits. Like much of the news, obits are a black box when it comes to who gets in and who doesn’t. There are luminaries who must get in. The other 40 percent are up for grabs.

The nature of news, of course, is that “all the news that’s fit to print” changes every day. Some days there is certainly more news that’s fit than others—and the newshole seldom changes to accommodate this ebb and flow. A front-page story one day gets shoved inside another day, and the same principle applies to obits. Spare a thought for Aldous Huxley, who had the misfortune to die on November 22, 1963—and thus was overshadowed by a much larger JFK obit the next day.

Stephen G. Bloom is the author of Postville, Tears of Mermaids, and Inside the Writer’s Mind. He teaches journalism at the University of Iowa.