“You filthy kunt…a baseball bat to your head is now due.”

“HOW FUCKING DARE YOU CUNT. GET THE HELL OUT OF THE BUSINESS…”

“Bitch, your days are numbered.”

“do the world a favor, go hang yourself”

“I hope you get raped to death”

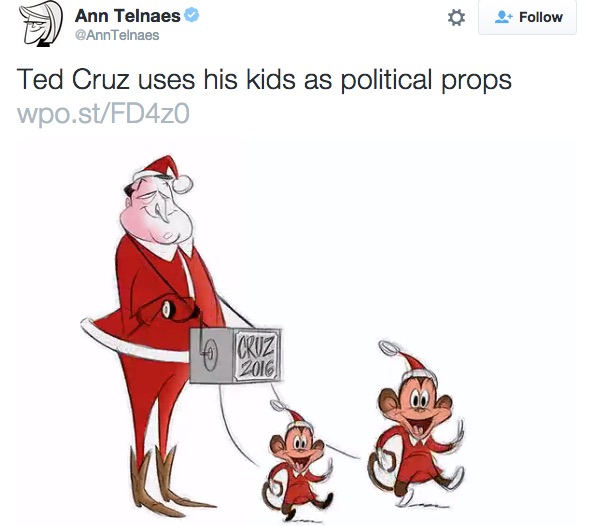

I stood frozen in front of my computer, watching my Twitter feed roll like a slot machine reel. My editorial cartoon criticizing then-presidential candidate Ted Cruz for his decision to have his 7-year-old daughter read from the script of a political attack ad had just been published online by The Washington Post, and four days of continuous emails, tweets, and comments had begun.

Since my cartoon ran in December, I’ve thought a great deal about the role of social media in stoking the resulting outrage. Although passionate criticism over a provocative cartoon isn’t new, the introduction of social media into politics and election campaigning has dramatically increased the speed and intensity of those reactions, and the repercussions for the editorial cartooning profession. This has been especially true during the volatile 2016 presidential campaign.

Ann Telnaes targeted this Ted Cruz ad.

Editorial cartoonists are a thick-skinned group; we’re used to getting negative feedback from irate readers telling us we’re idiots and how terrible our cartoons are. Many of my colleagues have received death threats as well—but this was different. In my almost 25 years as an editorial cartoonist, I have never received the level or amount of misogynistic vitriol I did over that cartoon. In addition to comments like the ones above, I was Twitter trolled, my archived cartoons doctored, and my photograph tweeted with the caption: “Makes fun of Ted Cruz’s children, aborted all of her own.”

Visual metaphors are an important component of editorial cartooning. They are the language we use to convey our point of view. The visual metaphor in this cartoon was an organ grinder, an early 20th century street musician who used leashed animals, usually monkeys, to collect coins from appreciative audiences. Because the point of my cartoon was to criticize Cruz’s decision to exploit his children for political gain, I drew him as a campaigning organ grinder with performing monkeys. This important part of the cartoon was lost immediately in the social media outrage fueled by tweets and comments from the senator and his supporters that mischaracterized the cartoon as attacking his daughters. The Washington Post pulled the cartoon within hours and replaced it with a note from Editorial Page Editor Fred Hiatt, saying, “It’s generally been the policy of our editorial section to leave children out of it.” That was when the Cruz campaign reprinted the cartoon in an email asking for political donations to fight the “vicious personal attack on my daughters.”

The cartoon Ann Telnaes created in response to Ted Cruz’s ad.

My colleague Joel Pett of the Lexington Herald-Leader had a similar experience last year with a cartoon criticizing Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin for his opposition to the resettlement of Syrian refugees—Bevin had claimed there was a possibility of terrorists entering the state. He called the cartoon racist because it mentioned his adopted children from Ethiopia, and he issued a statement condemning the newspaper for its racial intolerance and for attacking his kids. An online right-wing group picked up the story and continued the misrepresentation of the cartoon’s intent. For 36 hours, Pett and the Herald-Leader received phone calls, emails, and social media messages demanding apologies. Pett and his editor responded that the cartoon was not racist.

Pett’s experience, and mine, underscore how social media has changed the landscape for editorial cartooning—how it is being used as a tool of intimidation by interest groups and campaigns to try to silence criticism. Through social media they can quickly mobilize their supporters and distribute misinformation, allowing mob mentalities to spread as soon as a cartoon is posted online. The medium is lightning fast and provides the protection of anonymity. Add a news media that seems to value clickbait over presenting context about the editorial cartooning craft and often parrots the inaccurate characterizations the campaigns’ supporters spread, and you might as well paint a red bull’s eye on the cartoonist’s back.

During my four-day marathon of emails and tweets, I was trolled by a well known conservative cable news commentator who characterized my cartoon as attacking children and tried to bait me with insulting tweets. A member of the Cruz campaign communications team also trolled me, crowing that their “folks pushed back hard,” and “we won” after the cartoon was pulled. (Ironically, months later that same person was trolled herself with sexist tweets from Trump supporters.)

In the glut of coverage, most news outlets didn’t bother mentioning or showing the part of the video where Cruz had his daughter read from his political attack ad’s script. Except for a couple of print articles, including an informative piece by the New York Daily News that offered much-needed historical perspective about editorial cartooning, there was practically no coverage that explained what an editorial cartoon is supposed to do or the importance and use of visual metaphors. Instead there was outrage and talk about monkeys and children. Many of my cartooning colleagues pushed back with thoughtfully-written (and cartooned) arguments about the purpose of an editorial cartoon; had they not done so, I would have faced the equivalent of being tarred and feathered, with cable news talking heads leading the way with torches.

If we’re being harassed and pressured not to aim our pens critically, we won’t be able to call ourselves editorial cartoonists much longer–we won’t be able to create anything but mushy, uncontroversial drawings.

Let me be clear: Even in the face of this kind of attack, I am not advocating limiting people’s right to speak, however obnoxious and offensive the language is (threats are not included in this; threaten bodily harm, and that’s where your free speech ends). I would much rather have an abundance of stupid, ignorant speech (as this political season is giving us) than watch a slow slide into self-censorship and possibly worse for my profession, with cartoon police deciding what can or cannot be drawn. I have spoken out publicly in support of cartoonists to freely express themselves without fear of imprisonment or threats, including the Danish cartoonists in 2006 and the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists in 2015, both of whom published cartoons of the prophet Muhammad.

The big worry for editorial cartoonists these past several years has been the widespread loss of staff jobs as newspapers fold or choose to eliminate their cartoonist in favor of buying syndicated cartoons. Finding paying work online remains problematic for cartoonists. But the much bigger danger now is the use of social media to intimidate and silence, because it attacks the satirical core of what makes a cartoon an editorial cartoon. If we’re being harassed and pressured not to aim our pens critically, we won’t be able to call ourselves editorial cartoonists much longer–we won’t be able to create anything but mushy, uncontroversial drawings.

How should the journalism community protect cartoonists so they can do their jobs? We need to educate and be ready the next time a cartoonist aims his or her satire against a thin-skinned politician or interest group looking for an opportunity to manipulate fair criticism. Be aware when a false narrative is being presented to deflect the actual intent of a cartoon; talk to your editors and come up with a plan to counter the misinformation. Instead of just hopping on the social media outrage bandwagon gathering clicks, media outlets need to do their homework, explaining the role in holding powerful people accountable that editorial cartoonists have had for centuries in America. Educate yourself about the components of an editorial cartoon, and how satire, irony, caricature, symbols, and visual metaphors all contribute to its makeup.

The US Supreme Court affirmed the essential role of editorial cartoons in a democracy when it ruled in the 1988 Hustler v Falwell case that satire is speech protected under the First Amendment. “Despite their sometimes caustic nature, from the early cartoon portraying George Washington as an ass down to the present day, graphic depictions and satirical cartoons have played a prominent role in public and political debate,” conservative Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote in the majority opinion. “From the viewpoint of history it is clear that our political discourse would have been considerably poorer without them.”

We might be wearing the metaphorical funny hat, but we take our jobs as journalists very seriously. It has been said cartoonists are on the front lines of the war to defend free speech. Don’t make the job easier for the social media lynch mobs by ignoring the threat their attacks pose to that freedom.

Ann Telnaes creates editorial cartoons in various media—animation, visual essays, live sketches, and traditional print—for The Washington Post. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for her print cartoons in the Los Angeles Times. Her print work was shown in a solo exhibit at the Library of Congress in 2004. That same year, her first book, Humor’s Edge, was published by Pomegranate Press and the Library of Congress. A collection of Vice President Dick Cheney cartoons, Dick, was self-published by Telnaes and Sara Thaves in 2006. She is the incoming president for the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC).