Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

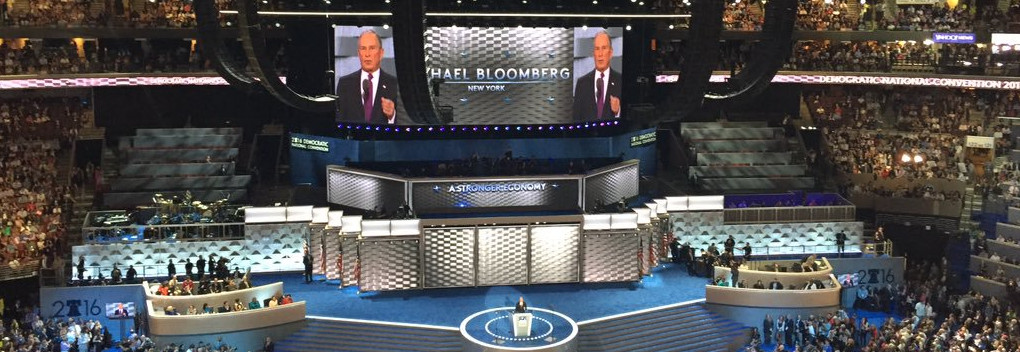

I was a 22-year-old rookie reporter for a local newspaper in the outer boroughs, making a salary that today would not even be New York’s minimum wage. It was January 2012, the second to last year of Michael Bloomberg’s mayoralty, and I tentatively typed out an email to Bloomberg’s hard-charging press secretary.

I wanted to know how “detrimental” Bloomberg believed it would be for New York City if the 2011 National Right-to-Carry Reciprocity Act became law. The act, passed by the Republican-controlled House with support from some Democrats, would have allowed non-resident gun-owners to carry concealed firearms across state borders. City Council had already passed a resolution condemning the bill.

Less than an hour after I hit “send,” Marc La Vorgna, Bloomberg’s press secretary, wrote me back personally. He said Bloomberg had been fighting this legislation for a long time, and offered me a series of links to make the case. As a young reporter working for a little-known outlet, it was striking to me how quickly Bloomberg’s team answered.

I’ve been a fierce critic of Bloomberg’s record as mayor and his decision to spend unprecedented sums of money on his presidential campaign. Whether it’s stop-and-frisk or spying on mosques, he has left behind a disturbing legacy that journalists are now rightfully scrutinizing again.

The man himself showed discomfort in press conferences and hated to be challenged. He called a New York Observer reporter a “disgrace.” He once accused me of smirking at him, and told me I should travel the world more to understand how poverty is relatively lacking in New York City. But his press office was the opposite: efficient, welcoming, and fully-optimized in the art of access journalism. Not exactly the behavior of a media-hostile urban strongman.

La Vorgna and Stu Loeser, La Vorgna’s predecessor, understood that most beat reporters are driven less by any particular ideology than a hunger for information—for anything that can, in ways superficial and occasionally not, beat the competition. I wasn’t immune to this.

Bloomberg’s press office knew that befriending reporters, or creating the appearance of camaraderie, was crucial to the mission. Off-the-record chats were frequent. So were after-work beers. Emails were always answered. As a young reporter at the bottom of the pecking order, I couldn’t claim to belong to the inner ring of these reporter-staff relationships. But I could still feel, in some way, that I knew Bloomberg’s team.

This would be thrown into sharp relief when Bill de Blasio became mayor. Campaigning as the anti-Bloomberg, the progressive who would clean up Bloomberg’s messes, de Blasio entered City Hall with a very different mandate. Reporters grew to hate him for his imperiousness, his tardiness, and the condescending way he occasionally lectured them, as Bloomberg would. (Some billionaires, it turns out, have learned to make their arrogance seem more digestible.)

Crucially, de Blasio’s original coterie of press secretaries weren’t as skilled at making reporters feel wanted. They blew off emails. They socialized less. In the first year, they doled out “exclusive” announcements to fewer outlets, chiefly relying on the New York Times. This infuriated beat reporters with other publications who were used to receiving first passes at policy or personnel announcements.

For the general populace, it doesn’t matter which outlet gets news first—who cares if it’s the Daily News or Post that reports on the hiring of a new deputy mayor before the other? But within the world of journalism, scoring these types of stories amounts to a show of force and an accumulation of status. It is ego gratification. And Bloomberg’s team understood that not only the Times should get fed.

Bloomberg endured, like any mayor, his fusillade of bad press—over stop-and-frisk, snow storms gone awry, his vacations to Bermuda—but his City Hall was much better at clamping down on negativity than de Blasio’s, which seemed to generate awkward or outright contemptuous headlines almost daily. Some of it may have been ideological. Some of it, on de Blasio’s end, was well-deserved.

The danger of access journalism is how reliant the mode becomes on powerful people who decide how to dole out information to the journalist. Increased access can distort the truth. For those working in politics who seek, in some way, to sway the media or at least mitigate the detrimental effects of a harsh story, the remedy is simple: provide more access.

Bloomberg’s City Hall did this. De Blasio’s, for a long time, struggled to, before appointing a press secretary in my final year of full-time City Hall coverage who made a concerted effort to share coffee or beers with young and veteran reporters alike. She, like Bloomberg’s staff before her, was doing her job in the hopes of netting more favorable coverage for her boss. It was incumbent on journalists, as always, to not be overly influenced by this outreach. A lousy or talented press secretary shouldn’t affect a reporter’s pursuit of the truth, though it does more often than it should.

In a 2019 Politico profile of Lis Smith, a former de Blasio aide who has since risen to prominence spearheading Pete Buttigieg’s presidential campaign, there is a quote from a campaign operative that stands out to me. John Weaver, a Republican who worked for John McCain and John Kasich, explains as bluntly as anyone why politicians and their staff pursue an access-journalism strategy—and why those who don’t are setting themselves up for failure.

“It’s really hard to do a hit piece on a guy who you are going to see the next morning over coffee and donuts,” Weaver told Politico. “It takes the edge off a bit. Maybe a story that would be 80-20 bad you can get down to 60-40 bad, and that little bit is worth it.”

Bloomberg, like de Blasio, wasn’t making himself available to reporters for coffee and donuts. But his top aides were. The presidential race is no different, with Loeser, La Vorgna, and other ex-City Hall staffers now working for Bloomberg 2020—familiar faces for a national press corps still dominated by those with New York City ties.

Bloomberg will continue to remain aloof, as he always does. His aides, knowing better, will fill the gaps, returning phone calls and emails and chatting, on the record and off, about how their billionaire can get to the White House. Not all of it will take the edge off. But, as Weaver says, getting an 80-20 bad story down to 60-40 is worth all the effort.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.