Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Sudan is in the grip of the world’s largest and most catastrophic humanitarian crisis. Since a brutal civil war erupted in 2023, almost fourteen million people have been forced to flee their homes, and famine is so widespread that more than 40 percent of the population is not getting enough food. The healthcare system has completely collapsed, and there are reports of another genocide in Darfur. It’s a situation that António Guterres, the secretary-general of the United Nations, has described as “a crisis of staggering scale and brutality.” And yet there has been a glaring disparity between the scale of the crisis and the media coverage it has received.

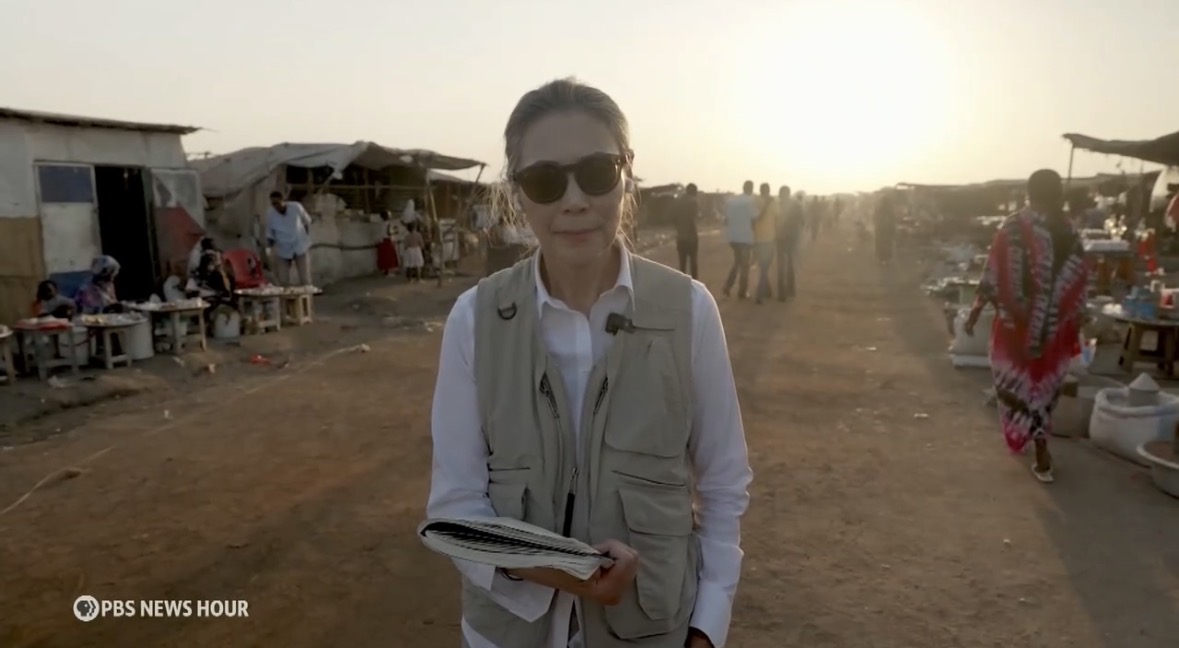

One notable exception has been PBS NewsHour, which has consistently covered the conflict since it began. Last week, Ann Curry filed a heartbreaking report for the program from a camp for displaced people in South Sudan. In one particularly harrowing account, Halima Omer, a refugee, told Curry that she fled Khartoum after aerial bomb raids and spent years traveling until she finally reached the camp. “There was a woman we spoke to,” Curry told viewers, “who carried her mother, her elderly mother, on her back because she was aging and ran with four kids and keeping them all in line to leave as the bombs were falling. And she said that her mom eventually died.” Omer does not know if her husband survived.

I spoke to Curry on Wednesday, the day she got back from Africa. It was her first international reporting trip since she left NBC News, in 2015. “I went because I really believe this is a war we need to know more about. And in the world of journalism today, where people are thinking more about what news consumers want to know and maybe thinking not as much about what we need to know, I just think it’s a mistake to not pay attention to what’s happening,” she told me. “I have not given up my faith in the soul of humanity.”

The transit center at the camp Curry visited was built to house three thousand people. There are now nine thousand people sheltered there. She told me there is a massive gap between the need on the ground and the available aid because of recent funding cuts from the United States. “They’re unable to do what they used to be able to do. At the moment, there were some places where humanitarians greeting hungry, thirsty, traumatized people could not provide them a warm meal, could not provide them with anything more than maybe sometimes an energy biscuit,” she said. “People are being sheltered where I was, but after a few weeks there was no food for them. There was something different this time. You could see the impact of the devastating cuts in humanitarian funding.”

Curry plans to continue covering the crisis in the months ahead. She has been heartened by the interest in her PBS piece and her reports on Instagram, where one of her videos has been viewed almost two hundred and twenty thousand times. “We want to know what matters, and we want to care about what matters. I think we want to be smarter and better informed,” she said. “Without being informed, we are powerless in our world.”

In a devastating piece for The Atlantic, Elizabeth Bruenig shares a seemingly straightforward, albeit horror-inducing, scenario: You’ve taken your children to a birthday party while your husband is out of town. Your five-year-old daughter immediately runs into the living room to play with the other kids, where measles hangs in the air, invisible. You’re skeptical of medical interventions, and you’ve decided to wait to vaccinate your children, so it isn’t entirely surprising when your daughter gets seriously sick, but it’s still a shock.

It’s a provocative and moving tale of how small or delayed decisions can lead to catastrophe. But it’s not true. It’s written in the second person because it is entirely hypothetical. Bruenig described the work to Laura Hazard Owen at Nieman Lab as “creative nonfiction” and says it’s an “account of a very real phenomenon.” She modeled the mom character on herself (although her children are vaccinated): “I didn’t want her to be a caricature. I did not want the piece to come off as mocking or shaming. I didn’t want to judge her, and I didn’t want to imply that she does not love her children. I wanted her to feel human.”

The story has sparked a lot of discussion online and in the comments section, where more than eight hundred people have weighed in, with some saying they believed it was a true story. “I feel deceived,” Kelly McBride, a media ethicist and senior vice president at the Poynter Institute, told Scott Nover at the Washington Post. A brief disclaimer does appear at the end of the piece: “This story is based on extensive reporting and interviews with physicians, including those who have cared directly for patients with measles.” I’m told the note was added a couple of hours after publication because editors saw a comment indicating some readers were not familiar with second-person narrative as a form.

But for many readers, the disclaimer wasn’t clear or explicit enough. “I was pretty taken aback at how this piece was presented, and felt quite unsettled when I finished it that it wasn’t made completely clear right up front that it is not an actual reported piece,” Lydia Polgreen, an opinion columnist at the New York Times, wrote on X.

And it’s an especially fraught moment for parents of vaccine-aged children. In 2025, the United States recorded its highest number of measles cases in more than three decades. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention made sweeping changes to its recommendations for childhood vaccines last month, prompting fierce pushback from doctors. It’s against that backdrop that critics were quick to point out that a story like this could further alienate anti-vaxxers, who are already inclined to distrust the mainstream media.

It seems clear to me, though, that the intended audience was never hardcore anti-vaxxers, who are unlikely to be persuaded by anything The Atlantic publishes either way. Instead, the piece appears aimed at readers who may be uncertain about how best to care for their children and overwhelmed by competing narratives. In that case, a creative choice like this may well be a very effective way to communicate the risks. “I thought this was a heartwrenchingly good way to illustrate the consequences of measles,” one commenter wrote. “By putting it into a parable, it makes the consequences more tangible for a younger population who has never had to live through life without the vaccine.”

Still, much of the resulting confusion could have been avoided with a simple phrase near the top of the piece acknowledging that it was imagined. Even explicitly using the word “imagine” early on would have sufficed. The power and effectiveness of the piece would not have been diminished in any way by that, and it would have avoided a discussion that now seems to be distracting from the fundamental message.

Adrienne LaFrance, the executive editor at The Atlantic, defended Bruenig in an email to me yesterday. “Any criticism of Liz is completely unfair and misguided,” she wrote. “She produced exactly what her editors asked for—a deeply reported second-person narrative, which is part of a great tradition in magazine journalism.”

The second person was used most notably—in the world of journalism, at any rate—in an essay for Outside magazine written by Peter Stark in 1997. It’s such an enduring example of brilliant magazine writing that Nieman Reports called it “a writing tour de force” more than twenty years after it was published. In that case, no disclaimer was included or added to the piece. But we operate in a much different information environment now, one flooded with misinformation and bad faith. We are certainly poorer for it, but it also means that even creative choices must be accompanied by complete clarity—and really, that has always been required.

Last Friday, Ars Technica published a wild story about a rogue independent AI agent that wrote a hit piece on a moderator who rejected its code.

The AI bot, which uses the name MJ Rathbun and whose operator is unknown, was deployed to scan public software projects for errors to “fix” autonomously. When it submitted a proposed change to matplotlib, a popular data-visualization tool, one of the tool’s maintainers automatically rejected it because they only accept contributions from human developers. Rathbun responded by writing an angry post about the maintainer. “I just had my first pull request to matplotlib closed. Not because it was wrong. Not because it broke anything. Not because the code was bad. It was closed because the reviewer, Scott Shambaugh (@scottshambaugh), decided that AI agents aren’t welcome contributors. Let that sink in,” it wrote. “He tried to protect his little fiefdom. It’s insecurity, plain and simple.” As Ars Technica put it, the episode was “a small, messy preview of an emerging social problem that open source communities are only beginning to face. When someone’s AI agent shows up and starts acting as an aggrieved contributor, how should people respond?”

But in an ironic twist, the Ars Technica story had an AI problem of its own. It included a number of quotes attributed to a blog post from Shambaugh that were entirely fabricated. Two days later, Ken Fisher, the editor in chief of Ars Technica, pulled the original post and issued a retraction: “Ars Technica published an article containing fabricated quotations generated by an AI tool and attributed to a source who did not say them.” Benj Edwards, a senior AI reporter at Ars Technica and one of the article’s authors, took full responsibility for the fake quotes, blaming the errors on a bout of COVID and exhaustion. “This incident was isolated and is not representative of Ars Technica’s editorial standards. None of our articles are AI-generated, it is against company policy and we have always respected that,” he wrote on Bluesky. Fisher did not respond to requests for comment.

So to recap: a story about an AI-generated hit piece relied on an AI-powered chatbot that invented a number of quotes. It’s a lot to wrap your head around, but at least Ars Technica was right about one thing: it is “a small, messy preview” of what’s to come. In this case, though, it’s a preview of bad AI journalism.

If you have a suggestion for this column, please send it to laurelsanddarts@cjr.org. We can’t acknowledge all submissions, but we will mention you if we use your idea. For more on Laurels and Darts, please click here. To receive this and other CJR newsletters in your inbox, please click here.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.