USA Today takes a long look at CEO perks, but it doesn’t do a good job of prioritizing the really egregious (ie newsworthy) ones. Its first anecdote is about Larry Ellison, the Oracle CEO who’s a billionaire forty times over:

Oracle spent $4,642 on legal advice for CEO Larry Ellison to help him figure disclosure requirements tied to his personal political contributions.The software maker also spent nearly $1.5 million for Ellison’s home security services.

Why would you put the $4,642 perk before the $1.5 million one?

Here’s the second perk USA Today lists:

Hormel Foods CEO Jeff Ettinger received $8.9 million in compensation last year. Most CEOs get nothing for attending corporate board meetings. But Ettinger gets $100 for each one — a Hormel perk since 1934.

Is this really even worth noting, much less using as your No. 2 anecdote? A hundred bucks a meeting for a benefit that predates the era of obscene executive compensation by fifty years?

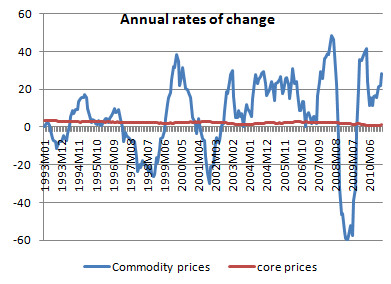

— Paul Krugman finds an IMF chart that shows why inflation hawks are wrong to focus on the headline CPI number rather than core number (which excludes volatile food and energy prices) to figure what inflation is doing:

Looks pretty clear to me.

— I know yesterday was a Monday and today is the 150th anniversary of the start of the Civil War, but why was this the lede story on page two of the Journal yesterday?

PENSACOLA BEACH, Fla.—Thousands of visitors from all over the world are expected to flock this month to Charleston, S.C. for a re-enactment of the bombardment of Fort Sumter, commemorating the beginning of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.

But it’s all quiet here at Fort Pickens, on a barrier island on the Gulf of Mexico, where President Abraham Lincoln once feared that the war would erupt.

Fort Pickens and Fort Sumter were the only two forts with U.S. soldiers remaining in the Confederacy by early 1861. Some top Union politicians believed Fort Pickens to be the more critical of the two to defend. Situated near one of the Confederacy’s largest ports, in the Deep South, it impeded rebel forces from importing goods and supplies from Cuba and the Caribbean that they sorely needed because the South lacked manufacturing plants. Fort Pickens was also easier than Fort Sumter to defend and re-supply, and further from the heart of the secessionist movement.

But it was Fort Sumter that took center stage when it was bombarded by and fell to Confederate forces on April 14, 1861, after two days of heavy shelling. To generations of Americans, it came to represent both a huge Confederate victory and a defiant U.S. resistance, “all things to all people,” said William B. Lees, executive director of the Florida Public Archaeology Network, based in Pensacola, Fla.

Fort Pickens, meanwhile, never came under heavy attack and remained in federal hands throughout the war—making it scarcely a point of pride for the defeated South.

I don’t understand the point of this one.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.