Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Slate got extra contrary last night, talking up the newspaper biz in a piece headlined “Newspapers aren’t doing as badly as you think.”

To which I can only say: Have you picked one up lately? The industry hasn’t been gutting newsrooms and newsholes just for the heck of it.

Daniel Gross says we’re making too much of the recent 10.6 percent decline in paid circulation, saying:

First of all, there’s nothing ipso facto shocking about a decline in patronage of 10 percent in six months. Many political blogs and cable news shows have seen their audiences fall by much more than 10 percent since the feverish fall of 2008. And advertising at plenty of online publications has fallen by a similar amount. In case anybody has forgotten, we’ve had a deep, long recession, a huge spike in unemployment, and a credit crunch. Consumers have cut back sharply on all sorts of expenditures. Many other components of consumer discretionary spending—hotels, restaurants, air travel—have fallen off significantly. Do we draw a line from trends over the last few years and declare that in 15 years there will be only a handful of hotels? I’m not sure why we would expect consumption of a purely discretionary item that costs a few hundred dollars per year not to fall in the type of macroeconomic climate we’ve had.

The decline is shocking. Sure, plenty of industries see 10 percent declines during cyclical downturns. The difference here is that this is a cyclical downturn on top of a secular one, and the circulation declines are far greater than any on record going back to early World War II. Couple that with advertising declines that are more than double that and you have a very real problem indeed.

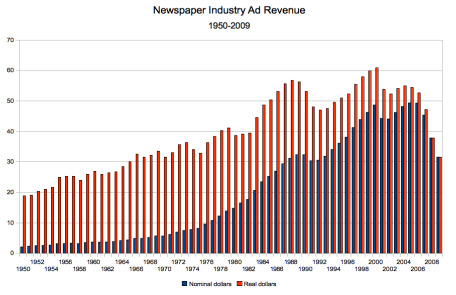

There have been circulation declines during recessions before but never anywhere approaching this size. The biggest (before the long-term secular decline began), from 1973 to 1975 was 3.9 percent—over two years! Granted this is the worst downturn since the Depression, which I don’t have data for. But the long term trend is clear from this chart (click through for a bigger version), which shows a mostly steady decline beginning in about 1987, one that started accelerating in 2004, three years before the recession began.

Gross doesn’t address the fact that the declines have shown no sign of slowing. Instead they’ve been accelerating. The last four six-month reporting periods have been steadily increasing percentage declines of 3.5, 4.6, 7.1, and now 10.6, as Martin Langeveld has pointed out. There’s a clear trend there. Maybe it will reverse itself in six months—or maybe it’ll head right on to 15 percent (some of this decline is due to an intentional strategy by newspapers to retrench into their core areas. How much is unknown).

Gross points to the increased subscription and newsstand costs as a potential savior, or at least tourniquet.

If raising subscription costs by 11 percent causes 10 percent of customers to flee, a newspaper will find that its circulation revenues are stable while it saves a lot of money by manufacturing a smaller number of newspapers.

But the average newspaper historically has taken in three or four times as much revenue from advertising as it has from circulation. In other words, if you lose 10 percent of your customers that advertisers want to reach, you’re probably going to lose somewhere near 10 percent of your advertising, which is needed to pay for things like reporting and editing. Think about it this way: If each subscriber/buyer is worth $1 in circulation revenue and $3 in advertising revenue, then even if increased prices help you break even on the circulation revenue, you’re going to have a far greater loss in advertising and thus net revenue if you lose that customer (for previous posts on the circ-revenue thing, see these from July about overall trends and about The New York Times getting more revenue from circulation than from advertising).

To stay afloat, that revenue loss has to, as Gross points out, be offset by cost-cutting, which has already gutted American newsrooms. There’s not a whole lot left to cut, and what’s already gone has made it much more difficult for papers to make that shift to more of a subscription-based revenue model, which would include charging online. If you keep jacking up the prices for a severely diminished product you give away free elsewhere, people are going to, especially in a bad economy, cut off that several-hundred-dollar-a-year subscription. Does anybody really think they’re coming back now that GDP’s gone positive?

The long-term trendlines are clear. They started before the Web even. There’s only one year with lower circulation numbers than what 2009 will end up being, and that’s the first year in the NAA records: 1940. Believe me, sometime next year we’ll have a new low.

Point being, it’s unlikely that any increase in circulation revenue will offset the loss of advertising revenue caused by fewer readers, much less that industry’s long-term shift away from the print medium. Last year print ads brought $35 billion in revenue. Circulation brought much less. The last year the NAA tracked it was 2004 at $11 billion. At best, the industry has tread water since then and most likely that number has declined. That gap is surely narrowing, but that’s not a good thing as that’s mostly because of declines in advertising, which is now at 1965 levels and dropping fast.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.