Here in Seattle, Amazon is growing like crazy, adding thousands of jobs and building several skyscrapers just off downtown, something that will add hundreds of construction jobs. But at what cost?

That’s what The Seattle Times asks in a tough, excellent four-part series that riffs off the company’s logo to go “Behind the smile in Seattle.”

I’m particularly interested in this series because I live here and because I’ve been critical of Amazon, a company I’ve given lots of business since 1999, when, like a true Gen X college kid, I bought a copy of The Baffler, a Nirvana book, and some Pavement Maxi singles, according to my order history on the site.

But the company’s anti-sales tax policies, which have included threatening to move if a state requires them to collect them like their competitors do, and the reporting we’ve seen in the last year on working conditions in its warehouses raise serious questions about how Amazon does business (and have caused me, for one, to buy elsewhere when possible).

With this series the Times has given us the most complete portrait yet of a corporate culture that leads to exploitative warehouse working conditions, monopolistic behavior, and an anti-tax battle to deprive states of revenue and maintain an unfair advantage in the marketplace.

Some of these behaviors are in the DNA of the company, embedded from the start by founder Jeff Bezos and his libertarian bent. Taxes particularly are a critical part of the Amazon origin story.

Bezos started Amazon in the Seattle area, the Times reminds us in its piece on the company’s anti-tax campaign, for tax purposes. The Supreme Court had just issued its ill-timed (right as the Web era was beginning) nexus ruling that said states couldn’t force companies to collect sales taxes if they didn’t have a physical presence there, and Bezos saw that this gave online retailers an unfair price advantage of up to 10 percent. He thought about locating on an Indian reservation, but that was “impractical,” in the Times words, so he went to Washington state, which had relatively few people, especially back then, which meant that fewer of his potential customers would have to be charged sales tax.

That was all well and good back then. But as the company has expanded and Internet retail has matured into a giant industry, it has continued to fight states that have tried to get it to collect taxes. And it plays hardball:

Code-naming their effort “Project ASAP,” South Carolina officials offered up more than $33 million in incentives, including free land, a property-tax cut and payroll-tax credits. They even agreed to loosen the area’s Bible Belt moral code, repealing a decades-old Lexington County “blue law” so Amazon’s warehouse could stay open Sunday mornings.

As they discovered, that wasn’t enough.

Amazon also insisted on an exemption from collecting the state’s 6 percent sales tax on purchases by South Carolinians. When the state Legislature balked, voting down the sales-tax break last spring, Amazon stopped construction on its million-square-foot warehouse and prepared to leave, throwing thousands of jobs into jeopardy

South Carolina caved, naturally.

Another of the four Times pieces looks at Amazon’s absence from the civic/philanthropic scene in Seattle. Unlike Boeing and Microsoft, the $85 billion giant doesn’t really give money to philanthropies, and it doesn’t encourage its workers to volunteer.

I have to admit, at first I thought this was a bit much. It’s not necessarily wrong for a company, particularly one with low margins, to not give money to charity. But after reading the entire series I changed my mind on the merits of the story: This is an essential piece of the puzzle The Seattle Times puts together.

Amazon isn’t an evil corporate citizen. It just doesn’t much believe in the concept of corporate citizenship. That’s its right, and it’s almost refreshing to see a sort of pure American capitalism devoid of gauzy marketing efforts to obscure that fact—however dependent it is on direct and indirect government subsidies.

Amazon’s gift to society, it says, is to run its business, which consists of “lowering prices, expanding selection, driving convenience, driving frustration-free packaging, creating Kindle, innovating in web services.” Some people would argue that that’s indeed the case, but you always have to question when someone claims their own self-interest is in the public interest.

And you can see how that ethos leads to the darker practices of the company. Dominant market positions are meant to be leveraged to get ever-more-dominant market positions, at the expense of suppliers and competitors. Governments are meant to be rolled on tax subsidies and tax avoidance. Workers are meant to be used up, discarded, and replaced with robots as soon as possible.

So as the Times asks what kind of $85 billion company doesn’t give money to parks and the United Way, the answer is: The kind of company that fights to avoid paying sales taxes for schools and firefighters. The kind of company that puts ambulances outside its warehouses to ferry the inevitable overworked heat victims to the hospital and then argues with the doctors about how they treat their patients so as to avoid triggering an OSHA report.

This anecdote is revealing about Amazon’s corporate culture, and it comes from an on-the-record executive:

Several current and former Amazon employees said they have wanted to change the company culture to encourage more giving. But colleagues told them not to bother — they’d be better off figuring out how to do good on their own.

“I kind of tested the waters by asking around and I got a sense it’s not worth pursuing,” Kintan Brahmbhatt, head of products for Amazon’s IMDb Everywhere initiative, recalled last year…

He asked about arranging to have charitable donations automatically deducted from his paychecks. But he learned that employees who do paycheck donations are charged a 6 percent fee from a company that processes them for Amazon.

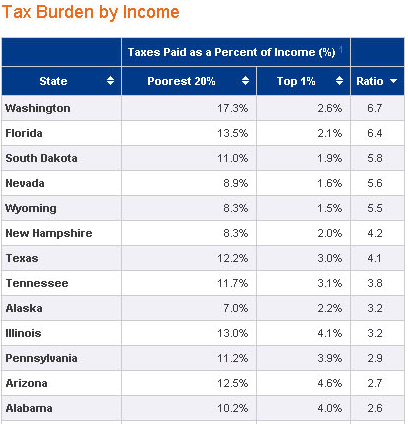

While Amazon doesn’t donate much time or money to its community, it also isn’t involved much in the kind of local corporate pooh-bah stuff like the Chamber of Commerce or Washington Roundtable. Unsurprisingly, though, Bezos personally gave $100,000 to defeat a proposal to levy a state income tax on the rich. Washington state has by far the most regressive tax system in the country, taxing poor people seven times as much as we tax the rich, as a proportion of income.

If you’re in the poorest 20 percent of Washingtonians, you pay an average 17.3 percent of your income in state and local taxes. If you’re in the top 1 percent, like Bezos or Bill Gates or Steve Ballmer or Howard Schultz and on and on, you pay 2.6 percent (and that surely overstates how much those super-rich folks actually pay). Lucky duckies, indeed. The state income tax Bezos helped defeat would have meant the richest 1 percent would have paid a little less than half the tax rate of the poorest 20 percent, up from one-seventh.

There is one big local donation the Times reports: The company pledged a couple million dollars to the University of Washington for endowed professorships in “machine learning.” That ought to help get its robots going, at least. Bezos is also dropping $42 million on a clock in a mountain in West Texas that will supposedly work for 10,000 years. I’m not kidding.

The Morning Call‘s excellent expose on working conditions in an Amazon warehouse near Allentown, Pennsylvania, showed how the company’s low-paid workers face bodily injury and the constant threat of termination. The Times follows up with a terrific report from Campbellsville, Kentucky that shows the Pennsylvania warehouse was no rogue unit:

A former warehouse safety official said in-house medical staff were asked to treat wounds, when possible, with bandages rather than refer workers to a doctor for stitches that could trigger federal reports. And warehouse officials tried to advise doctors on how to treat injured workers.

“We had doctors who refused to work with us because they would have managers call and argue with them,” he said.

These things come from the top, often from disconnected corporate managers getting pressured by their bosses who don’t see or don’t care how their orders play out on the ground, where human workers ultimately have to try to carry them out. The Times gets at that too:

“There would be phone conferences [with Seattle], and all this screaming, about production numbers. That was always the problem; the production numbers weren’t high enough,” said a former safety manager with oversight of the warehouse who spoke on condition of anonymity. “This was just a brutal place to work.”

And it uncovers a whistleblower, who unfortunately wouldn’t let his or her name be used, who was fired a week after questioning brutal working conditions in the Kentucky warehouse.

To make matters worse, Amazon is one of these places where people who have no other options go to make twelve bucks an hour and have to endure morning “pep talks” and creepy giant corporate slogans on the walls that say “work hard. have fun. make history.” Thanks for the history, bub. But a bump up to 500 bucks a week would surely motivate employees better.

Rounding out the paper’s portrait of Amazon, it looks at how it flexes its muscle in the book publishing market, where it accounts for an estimated 75 percent of print book sales online and 60 percent of e-book sales.

After the series appeared, Seattle Times Editor David Boardman wrote that readers swamped the paper’s website with negative comments. In less anonymous communications, unsurprisingly, like emails and phone calls, he says comments were much more positive.

Well here’s another one. Far too often, newspapers are homers for their big local employers. While it certainly didn’t hurt that Amazon isn’t a major advertiser, it still takes nerve to put out a tough investigation like this on a fast-growing local giant in a dire economy, and to deploy significant resources on it when there aren’t any to spare.

It’s also something that could actually make a difference. It’s one thing to get dinged in The Wall Street Journal, say. That hurts you in the markets, which are awfully important, but fairly abstract.

It’s quite another when it’s the local paper your friends and neighbors read.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.