Here’s how The Wall Street Journal framed its report yesterday on several states raising the minimum wage next year:

Small businesses, already on a tight budget, are looking for new ways to cut costs as they brace for minimum wage increases in several U.S. states next month.

The Journal‘s first anecdote is from a Vermont businessman who was one of George W. Bush’s top fundraisers (adding: which I found out via the Google):

“It’s a big deal,” says Skip Vallee, chairman and chief executive officer of R.L. Vallee Inc., a convenience-store chain with 60 locations in Vermont, New Hampshire and New York.

About half of R.L. Vallee’s roughly 450 employees make the minimum wage—mostly entry-level cashiers, sales associates and inventory-control personnel. To cope with the wage increases in Vermont, the 69-year-old family business plans to cut employees’ work hours in that state and is considering having employees there pay a larger share of the premiums for their employer-provided health insurance.

But how big a deal is it, really? Vermont’s minimum wage is going up 31 cents to $8.46 an hour. That’s a 3.8 percent increase, barely above inflation, which is running at a 3.5 percent annual pace. That context is unmentioned by the WSJ, as is any info on the last time it went up.

Vallee is going to have to give 3.8 percent raises to half his employees. For the sake of a thought experiment, let’s assume that all its minimum-wage employees are in Vermont and getting the forced raise. Assuming a forty-hour workweek for each, that would come to $145,000 a year in new labor costs. Throw in another 10 percent for taxes and it’s roughly $160,000 a year.

Seems like a lot in isolation, but this is a chain with sixty stores. To keep our back-of-the-envelope numbers going, assume again that half are in Vermont. That comes to $5,333 in raises per average store, or about $14.61 per store per day in higher wages. That’s 61 cents an hour per store in increased labor costs.

To put that $160,000 in more context, it’s exactly what Vallee makes per year just for his side job as a board member at MSCI Incorporated, according to Forbes data. And it’s much less than the $200,000 Vallee raised as a George W. Bush campaign bundler a decade ago, which turned into a plum gig: ambassador to Slovakia.

It’s also less than Vallee and his wife themselves donated directly to Republicans in just one year—2004.

RL Vallee is private so it’s hard to tell what its finances are like or what Vallee pulls out of the company per year. But there ought to be a new rule: No quoting an owner or CEO on how he can’t afford to give 31-cent raises unless he tells you how much money he makes a year.

The Journal gets a bit of “to be sure” in after the Vallee paragraphs by quoting an academic who’s studied whether relatively small minimum wage increases affect employment:

There is no “evidence of any loss of employment or hours for the type of minimum-wage changes we have seen in the U.S. in the last 20 years,” says Arindrajit Dube, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

But then it blows it by following that quote with this he said-she said:

But opponents argue that minimum-wage increases do have unintended consequences. “When you raise the price of something, including entry-level labor, you’re going to decrease demand for it,” says Michael Saltsman, research fellow at the Employment Policies Institute, a nonprofit research group in Washington, D.C.

The Employment Policies Institute, a “nonprofit research group in Washington.” Sounds sober, objective, and authoritative, right—equivalent in stature to peer-reviewed academic research, right?

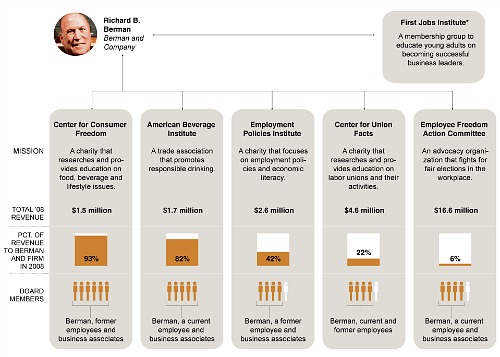

Uh, no. It’s a front for the lobbyist/flack Richard “Dr. Evil” Berman, attack dog for the minimum-wage-heavy restaurant industry and folks like Big Tobacco (and “An exploiter. A scoundrel. A world historical motherfucking son of a bitch,” according to his son, David Berman of the late great Silver Jews).

It’s not surprising that the story is framed this way, since it’s surely an Employment Policies Institute press release-driven piece. The Star Tribune and Orange County Register both had stories noting the rise in state minimum wages the day before the Journal piece. Both also cited the Employment Policies Institute and neither noted its background.

A big boo. You can’t cite something with one of those names that makes it seem like a dowdy think tank without pointing out that it’s a front group for corporate interests. Readers have a right to know where their information comes from.

The Journal does give us some numbers down in the story on how a company’s costs might increase:

Martin O’Dowd estimates a pending 36-cent increase in the minimum wage in Florida to $7.67 an hour will add up to more than $1 million in annual operating expenses for the 30 Hurricane Grill & Wings restaurants outlets he owns there.

But even this isn’t worth much without context. How much are the company’s overall operating expenses? What’s its profit? Does it expect to pass on higher labor costs to customers via slightly higher menu prices? We’re not told.

There’s also no context here about how low the minimum wage has gotten. Back in the 1960s, the minimum wage was about $10.41 an hour, or 44 percent more than it is now, and the economy was good. The highest minimum wage in the country today is in San Francisco, an astronomically expensive city, where it’s $9.92 an hour ($10.24 next month).

I don’t mean to imply that the story is all bad. If you make it that far, the Journal‘s kicker is nice, for instance:

Initially, he paid some plant workers the lowest wages possible. But when he later decided to give out raises that exceeded the minimum required, he says he gained a more loyal work force. Today his lowest-paid staffers earn $11 an hour. The minimum hourly wage that employers must pay in Montana will rise 30 cents to $7.65 next month. “Our turnover dramatically reduced and the engagement level from our employees rose,” he says.

But framing matters, as does context, particularly when quoting astroturf shops.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.