Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

When I was a young reporter for The Oregonian in far-off Portland, my friends and I seethed over each new outrage in the South. The 1955 torture and murder of Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, triggered a special revulsion. We wanted to impose racial justice on murderous bigots. We were certain that change had to be forced down the throats of the South. Civil Righteous, you could have called us.

Force seemed ever more imperative when I came to Washington, DC, in 1961, working as a press assistant for Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Wallace Turner, a mentor at The Oregonian and a Pulitzer Prize winner, recommended me for the job to RFK’s director of public information, Edwin Guthman, himself a former Pulitzer winner. I soon came to recognize how these men, and relatively few principled Southern editors, reporters, columnists, and photographers, participated in the destruction of Jim Crow, the brutal caste system imposed through the South after slavery. And I learned afresh how much hate, blood, and death that change would demand of black Americans.

Only a few weeks after I arrived, all of us in the AG’s office were horrified when a Montgomery street mob attacked the Freedom Riders and brained RFK’s assistant John Seigenthaler with a pipe. Likewise, working the phone through the night of the 1962 riot at Ole Miss, I remember fearing for Ed Guthman, Deputy Attorney General Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, and many US Marshals in the embattled Lyceum building, under attack by a howling mob. At one point, shaken, I called the White House to report that Paul Guihard, a red-haired French reporter, had been caught in the mob and killed.

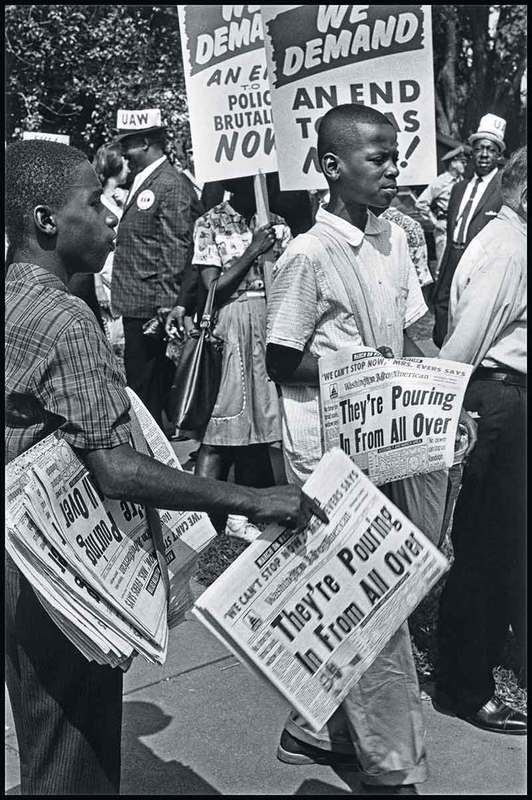

Paper boys distribute the day’s headlines at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963. (Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos)

I was young then, and it all seemed simple. President Kennedy had committed the federal government to eliminate Jim Crow. Why wasn’t everybody just getting on with it?

So it was perplexing to encounter the disciplined restraint of Burke Marshall, the Justice Department’s civil rights chief. He reviled Jim Crow-—but he also understood the limits of the federal system, the difficulty of forcing change down anyone’s throats, and the need to protect the civil right that is basic to all the others, the vote. As he wrote in 1964, “Only political power—not court orders or other federal law—will insure the election of fair men as sheriffs, school board members, police chiefs, mayors, county commissioners and state officials.”

Stop for a moment and think about those words, “fair men.” Consider how much they tell about Burke’s faith in democracy and how they transcend vengeance or anger. It may have been as difficult for Justice officials like Burke, Nick Katzenbach, John Doar, and Louis Oberdorfer to teach political reality to impatient liberals as it was to conquer the dangerous demagoguery of Southern governors—let alone the physical danger of swaggering sheriffs and snarling dogs. Only after years of perilous field work by Department lawyers and then the transformative Voting Rights Act of 1965 did the political process start to work: Throughout the South, fair men and women began speaking out.

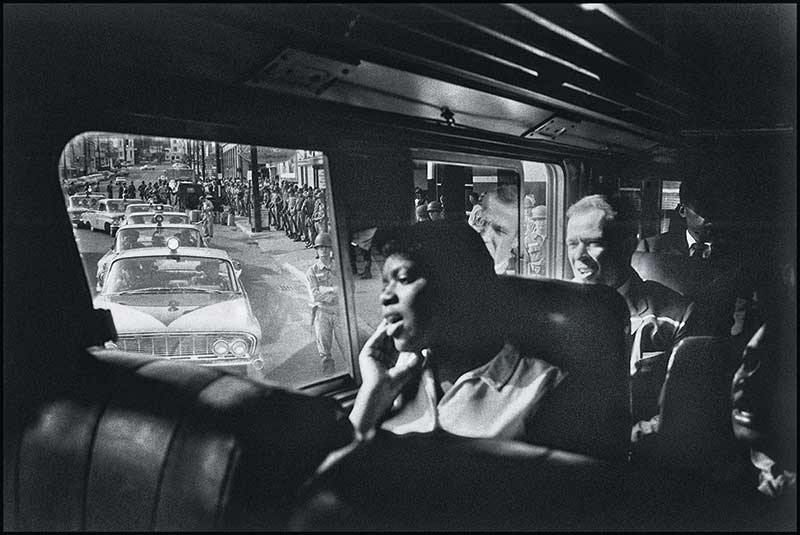

Freedom Riders are escorted along their route from Montgomery, Alabama, to Jackson, Mississippi, by the National Guard, 1961. (Bruce Davidson / Magnum Photos)

In good measure, they did so because a few journalists—unlike most white publishers and editors across the South—dared to speak out. After World War II, first a brave few and then a cadre of writers and editors described and denounced the cruelties, beatings, and lynchings that eventually woke up Southerners of good will—and shocked the country. Their work in this war on Jim Crow brought, to many of them, journalism’s medal of honor, the Pulitzer Prize. Their stories offer inspiration to future generations of journalists.

Some spoke out editorially as the conscience of their communities—even at the risk of provoking violent response: Pulitzer Prize winners like Ralph McGill and Eugene Patterson of The Atlanta Constitution, Jonathan Daniels of the Raleigh News & Observer, and Hazel Brannon Smith of the Lexington, Mississippi Advertiser. Consider McGill’s prescient words in a column in April 1953:

[O]ne of these Mondays the Supreme Court of the United States is going to hand down a ruling which may . . . outlaw the South’s dual school system, wholly or in part. It is a subject which . . . usually is put aside with the remark, “Let’s don’t talk about it. If people wouldn’t talk about these things, they would solve themselves.”

It is an old reaction, best illustrated by Gone With the Wind’s Miss Scarlett O’Hara who, when confronted with a distasteful decision, pushed it away with the remark, “We’ll talk about that tomorrow.” But “tomorrow” has an ugly habit of coming around. . . . So, somebody, especially those who have a duty to do so, ought to be talking about it calmly, and informatively.

Other journalists, often at risk to themselves and their families, reported unflinchingly on guns, dogs, mobs, and hate. Some were Southerners like John Herbers and Cliff Sessions, who sent unvarnished United Press International reports around the country and world; Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times; and Brandt Ayers of the Anniston, Alabama Star. Others represented national outlets, like John Chancellor of NBC, who scored original inside reports from Little Rock; Karl Fleming of Newsweek, whose head was later bashed in at a Black Power rally in Los Angeles; Adam Clymer of The Baltimore Sun, who was sucker-punched in Selma; and Carl Rowan of The Minneapolis Tribune. Photographers like freelancer Bob Adelman, Charles Moore of Life, and Bill Hudson of the Associated Press were singled out for attack.

Pallbearers in Birmingham, Alabama, carry the casket of one of the four girls killed in the KKK bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, 1963. (Danny Lyon / Magnum Photos)

The exemplary journalism of them all is richly documented in The Race Beat, the book by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff that was justifiably honored with a Pulitzer Prize, and which helped me immensely for this piece. Three stories typify that work over two decades: the editorial voices of Hodding Carter Jr., editor of the Greenville, Mississippi Delta-Democrat Times, and Harry Ashmore, editor of the Arkansas Gazette, and the day-to-day reporting of Claude Sitton, Atlanta bureau chief of The New York Times for six tumultuous years.

Tearing down Jim Crow took the courage, torture, and death of untold black Americans well over a century. The press—not yet called the media—nevertheless played a potent role.

In time, the country—notably the churches—became aroused. But over many years, the life-and-death actors were not white observers. Tearing down Jim Crow took the courage, torture, and death of untold black Americans well over a century. The press—not yet then called the media—nevertheless played a potent role. As Gunnar Myrdal concluded in his seismic 1944 study, An American Dilemma: “[There] is an astonishing ignorance about the Negro on the part of the white public in the North. . . . There are many educated Northerners who are well informed about foreign problems but almost absolutely ignorant about Negro conditions both in their own city and in the nation as a whole. . . . To get publicity is of the highest strategic importance to the Negro people.”

Carter became an early, consistent champion of fairness. Before long, Ashmore, also impressed by Myrdal, brought singular principle to his paper’s editorial page. And in the dramatic, bloody later years, Sitton proved to be a paragon of daily reporting.

Hodding Carter Jr. was a son of Louisiana who, according to his biographer, as a young man espoused racist views. In 1939, he started the Greenville, Mississippi Delta Democrat-Times. His service in World War II gave him a broader perspective.

In 1945, he wrote a series of editorials resonating with tolerance and fairness, like his elegy for Bobby Henry, a former newsboy who won the Medal of Honor for attacking five German machine gun nests. “When someone tells us that the kids of today and of a few years ago aren’t worth much,” Carter wrote, “we’ll tell them about Bobby and a few others we remember. When they tell us their prejudices, we’ll tell them about the prejudices of the men against whom Bobby charged.”

For writing a series of editorials resonating with tolerance and fairness, and ridiculing the racists in positions of power, Carter was awarded the Pulitzer for editorial writing in 1946. His voice grew steadily stronger.

Subsequently, he ridiculed Mississippi’s bombastic racist Senator Theodore Bilbo in an editorial titled, “On Being Bilboed.” Names sometime become common words, he wrote, like pasteurize and quisling. “It won’t be long before the dictionaries will be including as a common noun and verb the word bilbo . . . to seek to destroy the character of another . . .”

These editorials were among those the Pulitzer Prize committee chose for the editorial award in 1946. His voice grew steadily stronger. Many Southern editors denounced the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education striking down separate but supposedly equal schools. It took courage for a Mississippi editor to write:

If ever a region asked for such a decree, the South did through its shocking, calculated, cynical disobedience to its own state constitutions, which specify that separate school systems must be equal. For 75 years, we sent Negro kids to school in hovels and pig pens. . . . [The South must] replace trickery and subterfuge in our educational structure with an honest realization that every American child has the right to an equal education.

Likewise, few editors had the nerve to attack the white Citizens’ Councils that sprang up in the wake of the Brown decision. In March 1955, Carter did more than that, not just in his paper but with an article in Look, the national magazine, titled “A Wave of Terror Threatens the South.” For that, by a vote of 89 to 19, the Mississippi House of Representatives denounced him as a liar. In response, “by a vote of 1 to 0,” he wrote, “there are 89 liars in the State Legislature.”

Beyond his own writing, Carter served as a mentor to visiting journalists. Later, Hodding Carter III, his successor, continued the brave tradition of fairness and reason even in the face of mob violence like that surrounding the registration of the first black student at the University of Mississippi. To avoid that, it was rumored that Governor Ross Barnett was about to close Ole Miss. Massive resistance, the younger Carter wrote, was pointless and dead certain to be a losing strategy. Barnett should know that, yet “for the sake of a philosophy which sees some men as inherently inferior to others,” the governor might force the university to close “in one highflying burst of idiocy.”

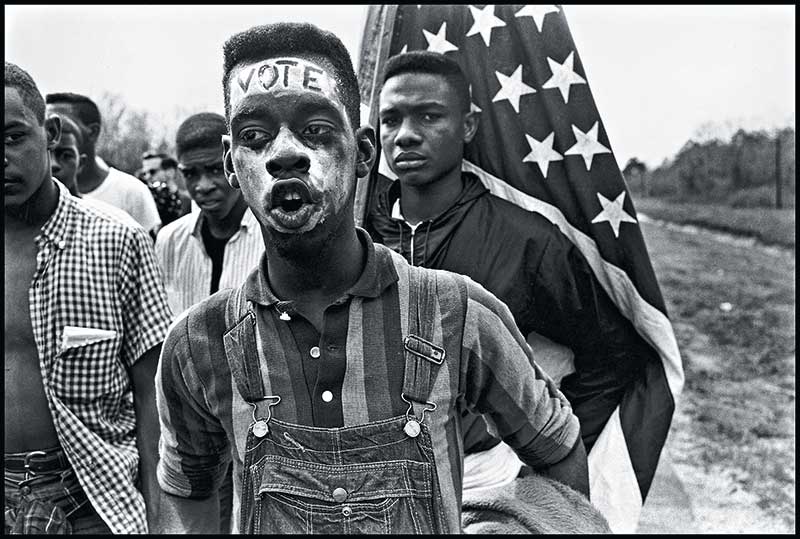

Led by Martin Luther King Jr., a group of civil rights demonstrators marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to fight for black suffrage, 1965. (Bruce Davidson / Magnum Photos)

Years later, in 1993, in a New York Times review of a Carter biography by Ann Waldron, Claude Sitton testified to his legacy: “[R]eaders of today will ask how an editor who opposed enactment of a federal anti-lynching law as unnecessary and public school desegregation in Mississippi as unwise can be called a champion of racial justice. The answer, which she gives in the book’s introduction, lies in the context of the times. Absent his efforts and those of other Southern editors of courage and like mind, change would have come far more slowly and at far greater cost.”

Probably no one gave fuller meaning to those words than a young editor in Arkansas.

An American Dilemma made a deep impression on Lt. Col. Harry Ashmore. As a paper boy, he had delivered newspapers in poor black neighborhoods of Greenville, South Carolina. After college, he reported for small papers before serving four years as an infantry officer in World War II. Then he encountered Myrdal’s monumental work and shared views with Ralph McGill in Georgia and Hodding Carter in Mississippi. He returned to journalism and in 1947 went to Little Rock as editor of the Arkansas Gazette.

Ashmore recognized the susceptibility of public attitudes to rumor and outright lies. So in 1953, while remaining at the Gazette, he accepted a Ford Foundation invitation to direct its encyclopedic study, “The Negro and the Schools.” That in turn prompted him to create the Southern School News, which became for a decade an authoritative source of desegregation news around the region.

Ashmore brought singular principle to his paper’s editorial page, fighting for integration in Little Rock public schools. Also the founder of the Southern School News, which was an authoritative source of desegregation news around the region for a decade, Ashmore took home the Pulitzer in 1958. (Grey Villet / Getty Images)

Then the story came to Ashmore. In September 1957, the Gazette carried a perverse sign of the times: a full-page ad from the Ford Motor Company introducing the Edsel (“More than a new make of car”). Meanwhile, the news columns reported that, on the eve of the desegregation of the Little Rock schools, Governor Orval Faubus had reversed his earlier acceptance of court orders and sent in the National Guard. In a front-page editorial on September 4, Ashmore wrote “[The problem] is one he must now live with, and the rest of us must suffer under. If Mr. Faubus in fact has no intention of defying federal authority, now is the time for him to call a halt to the resistance which is preventing the carrying out of a duly entered court order. And certainly he should do so before his own actions become the cause of the violence he professes to fear.”

As Faubus insisted on challenging the courts and also President Eisenhower, Ashmore worked tirelessly to provide clarity in the news columns and to support legality in his editorials, repulsed by “these reckless men” who made “Little Rock . . . the scene of historic tragedy.” In nominating Ashmore for the Pulitzer Prize, his publisher told of watching him write editorials on deadline, even “sometimes in takes.”

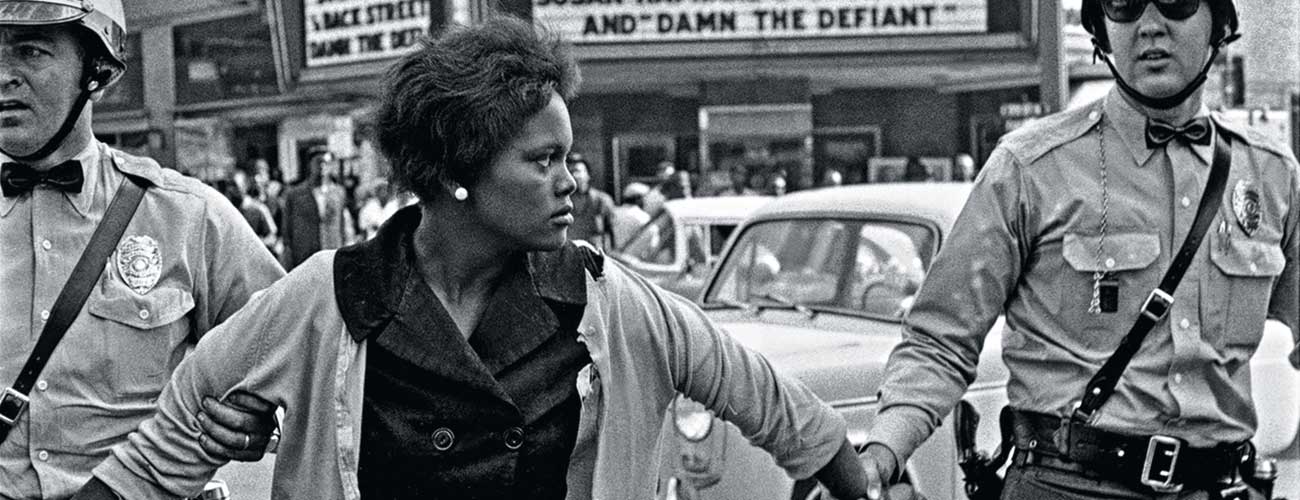

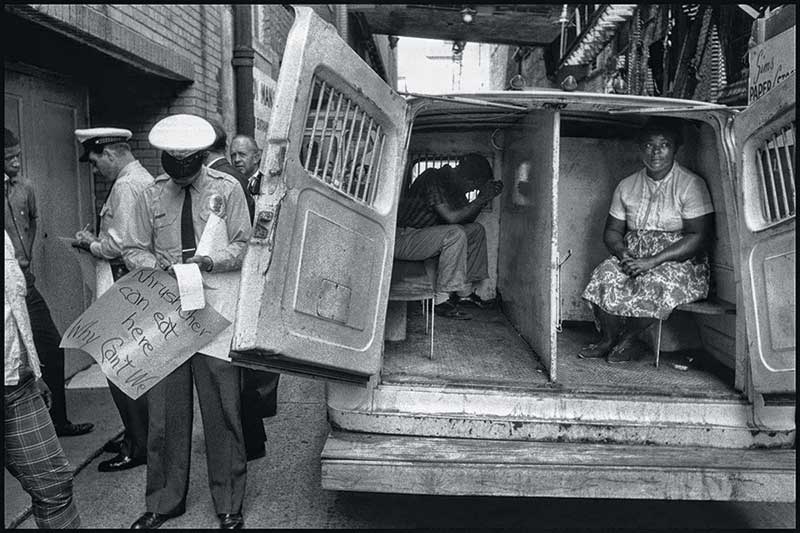

A woman waits in the back of a paddy wagon in New York City, 1962. (Bruce Davidson / Magnum Photos)

As the crisis deepened, Ashmore wrote on September 21 that, contrary to Faubus’ sudden shift, “[There are] responsible public officials who believed—and so testified under oath—that they could have resolved a difficult social problem in good order and with good will had Orval E. Faubus not refused their pleas for support and instead embarked upon a course that invited violence and disorder.”

On October 3, he spelled out some threats: “Many decent citizens have been threatened with anonymous calls. It is, we know, hard for any of us to retain his perspective when the air is filled with rumors carefully designed not only to distort the truth, but to promote panic. But we know, too, that we are a people who cannot be finally intimidated—a people who will not let a minority rule them by terror. We in Little Rock believe in law and order, and when we speak out for it again we shall have it.”

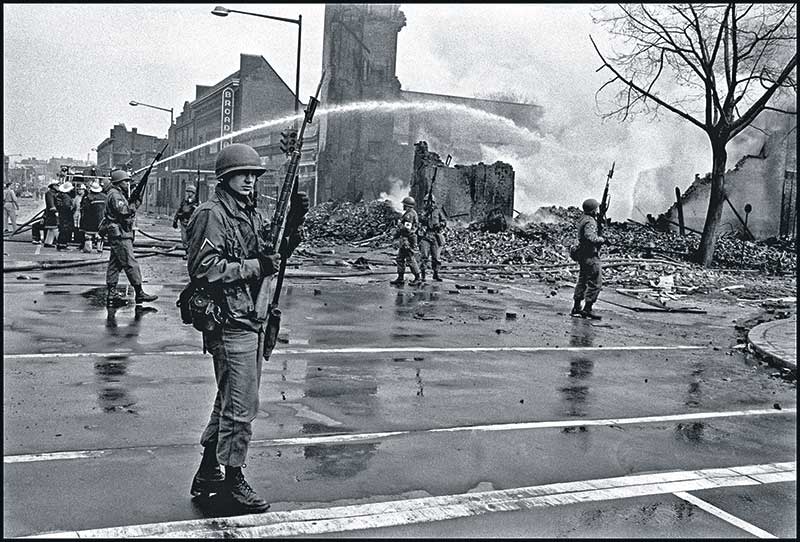

The morning after the riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the National Guard patrols the streets in Washington, DC, 1968. (Burt Glinn / Magnum Photos)

Three weeks later, Ashmore summarized both the issue and the role of the press in these words: “We believe Mr. Faubus knows exactly what he is doing—and we suspect we have earned his wrath. Because through accurately reporting his devious course step by step, we have shown precisely where he is taking the people of his state in the furtherance of his political ambitions, and the terrible price all of us are going to have to pay as a result.”

Apart from his work as an editor and editorialist, Ashmore—like Carter in Mississippi—also played a constructive role as genial host and mentor for the national press corps encamped in Little Rock. In his Pulitzer nomination, Ralph McGill, grand old man of honorable Southern journalism, gave Ashmore the finest compliment: “I know of no crisis in our time which has provided a better illustration of journalistic service by an editor on a newspaper.”

Like Carter and Ashmore, Claude Sitton was an unquestioned son of the South. His great-grandfather was a tax collector for the Confederacy; a maternal grandfather was a circuit-riding preacher in the hills of Georgia. Also like Carter and Ashmore, he was drawn early to journalism. As an Emory student, he was impressed when Ashmore and Ralph McGill came to lecture. After several years as a wire service reporter, Sitton was hired as a copy editor at The New York Times and became the Times’ Southern bureau chief in 1958.

He came back to a South that had become a harsher place. He covered the second year of the Little Rock school crisis, the rise of Citizens Councils, and, in 1960 in Raleigh, the first sit-ins.

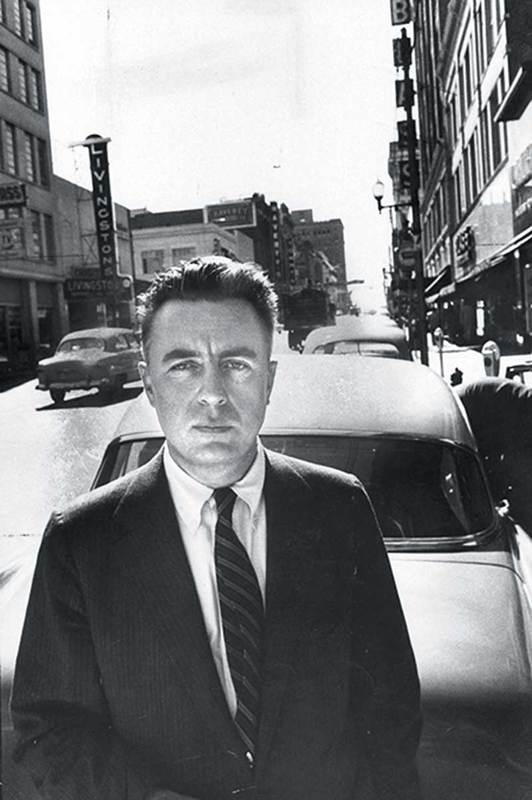

The quality, let alone the quantity, of Sitton’s work soon made him a model for the growing corps of national reporters assigned to the race beat. He expressed consistent convictions on equality for decades, eventually winning the Pulitzer for commentary in 1983. (Associated Press / The New York Times)

“[E]ven for a southerner who had grown up with the prototype of the segregationist, he was shocked again and again by the meanness that pervaded the resistance, particularly among the diffident men in suits who did little to discourage the bullyboys who were willing to get their hands bloody.”

At times, he would work for six weeks straight without a day off. The quality, let alone the quantity, of his work soon made him a model for the growing corps of national reporters assigned to the race beat. That was especially true for TV correspondents; the networks did not expand their nightly news to half an hour until 1963. As noted in The Race Beat, his page one Times story on February 15, 1960, soon after the first sit-ins, typified the work that quickly attracted other journalists:

CHARLOTTE, N.C., Feb. 14—Negro student demonstrations against segregated eating facilities have raised grave questions in the South over the future of the region’s race relations. A sounding of opinion around the affected area showed that much more might be involved than the matter of a Negro’s right to sit at a lunch counter for a coffee break.

The demonstrations were generally dismissed at first as another college fad of the ‘panty-raid’ variety. This opinion lost adherents, however, as the movement spread from North Carolina to Virginia, Florida, South Carolina and involved fifteen cities. Students of race relations in the area contended that the movement reflected growing dissatisfaction over the slow pace of desegregation in other public facilities.

In time, Newsweek came to declare that “The best daily newspaperman on the Southern scene is the Atlanta-based Sitton. An indefatigable stickler for facts, Sitton is so trusted and widely known in the South that telephone calls follow him wherever he goes.”

He continued to follow the civil rights story closely when he became national editor of the Times in 1964 and then, starting in 1968, when he took over the Raleigh News & Observer. As a columnist, he expressed consistent convictions like those that won him the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1983. For example, in May 1982, in words that reverberate today, he wrote: “The Constitution imposes no neutral . . . role on government. There can be no equality of constitutional and legal rights without the government’s active intervention. And the widespread inequality that still exists today demands such action.”

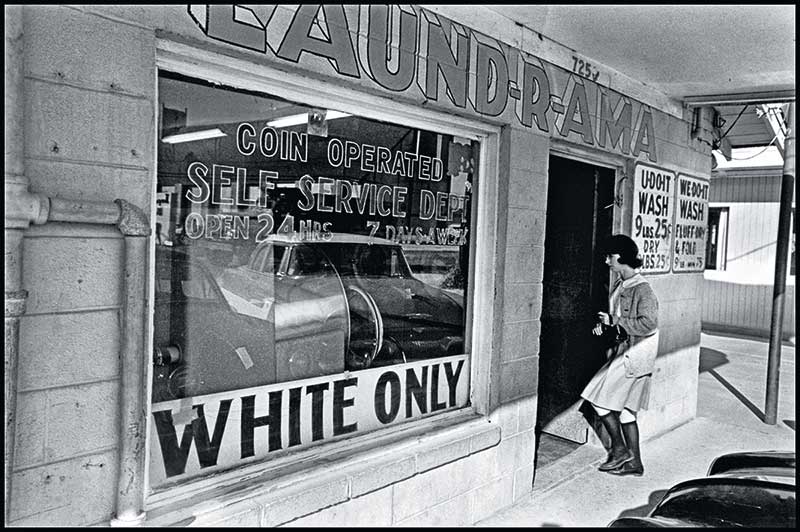

A woman walks into a segregated laundromat in New Orleans, Louisiana, 1963. (Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos)

On July 4, he wrote: “How ironic that man asserts this freedom to assert his natural heritage in a day when the word “conservative” slides smoothly from many tongues. The word has become a shibboleth, a trendy political cachet, a catchword to country club accessibility. The disdain for conservation proves it.”

While still at the Times, Sitton not only reported the news; he anticipated it. In a News of the Week analysis in February, 1964, he wrote that “The carefully scrubbed, neatly dressed college students who sat down at lunch counters across the South in 1960 and politely ordered coffee are gone for the most part. It has become increasingly apparent that many Negroes are no longer willing to listen to the voices of reason within their own ranks. They do not especially care what whites think about them and their tactics.”

The civil rights movement burst apart and ahead, past the Birmingham church bombing, Freedom Summer, and the murders in Neshoba County, Mississippi; past the bloody Pettus Bridge in Selma, the murder of Medgar Evers, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That monumental legislation, by enabling thousands of blacks to vote and bringing to office the fair men of whom Burke Marshall wrote, would seal the fate of the oppressive caste system and the death of Jim Crow.

After World War II, first a brave few and then a cadre of writers and editors described and denounced the cruelties, beatings, and lynchings that eventually woke up Southerners of good will—and shocked the country.

At the same time, as Sitton anticipated, street demonstrations arose in hundreds of cities in the North and South. The Watts riot in 1965 brought death and destruction to Los Angeles. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 ignited riots in major cities. Moneta Sleet of Ebony won the Pulitzer Prize in 1969 for his photo of Coretta King at Dr. King’s funeral. President Johnson appointed a Commission on Civil Disorders, the Kerner Commission, which concluded, in language I drafted, that “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” It went on to say, “What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

The Kerner report, The New Republic wrote, fired “a pistol shot in the ear of the American public.” And yet, a half century later, black Americans are still compelled to take to the streets to declare that Black Lives Matter. Bryan Stevenson, lawyer, teacher, and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, recently reviewed the history of race relations for The Marshall Project, saying: “I don’t believe slavery ended in 1865. I believe it just evolved. It turned into decades of racial hierarchy that was violently enforced—from the end of reconstruction until WWII through acts of racial terror. And in the north, that was tolerated.”

Journalists like Hodding Carter, Harry Ashmore, and Claude Sitton could not end such terror. But, armored with the prestige of the Pulitzer Prize, they did their honorable part.

Ronald Reagan was the Teflon President, shielded with unusual deference from the acrimony of Washington. He promised a country strained by a weak economy that it would rise again, propelled by the ideal of American exceptionalism.

In 1981, an editorial writer named Jack Rosenthal was in his 12th year at The New York Times. He wasn’t buying Reagan’s vision of America. He thought the new administration was tearing the social safety net erected by previous presidents. He didn’t think the economic reforms would reform anything. He didn’t understand why others weren’t speaking up.

One of Rosenthal’s editorials read: “Mr. Reagan believes that, if the administration persists in its program, the tide will turn. A more apt maritime image is offered by Herbert Stein, economic advisor to President Nixon. ‘If the captain of the ship sets out from New York harbor with a plan of sailing north to Miami, steady as you go will not be a sustainable policy and that will be clear before the icebergs are sighted.’ ”

Rosenthal won the Pulitzer for editorial writing that year. The jury, one member reported, credited him for speaking up when others weren’t.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.