Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Last Tuesday, after nearly two weeks of air strikes, Israel sent ground troops into Lebanon to fight Hezbollah. It was another significant escalation in a war that has, over the past year, devastated Gaza and swaths of Beirut and alienated Israel from many in the international community. But beyond a vague feeling of unease, a handful of protesters, and perhaps a slight increase in the number of helicopters flying overhead, it was a calm morning in Tel Aviv. Commuters strapped helmets on their kids and biked them to school. Joggers ran along the boardwalk. City buses rumbled down the streets.

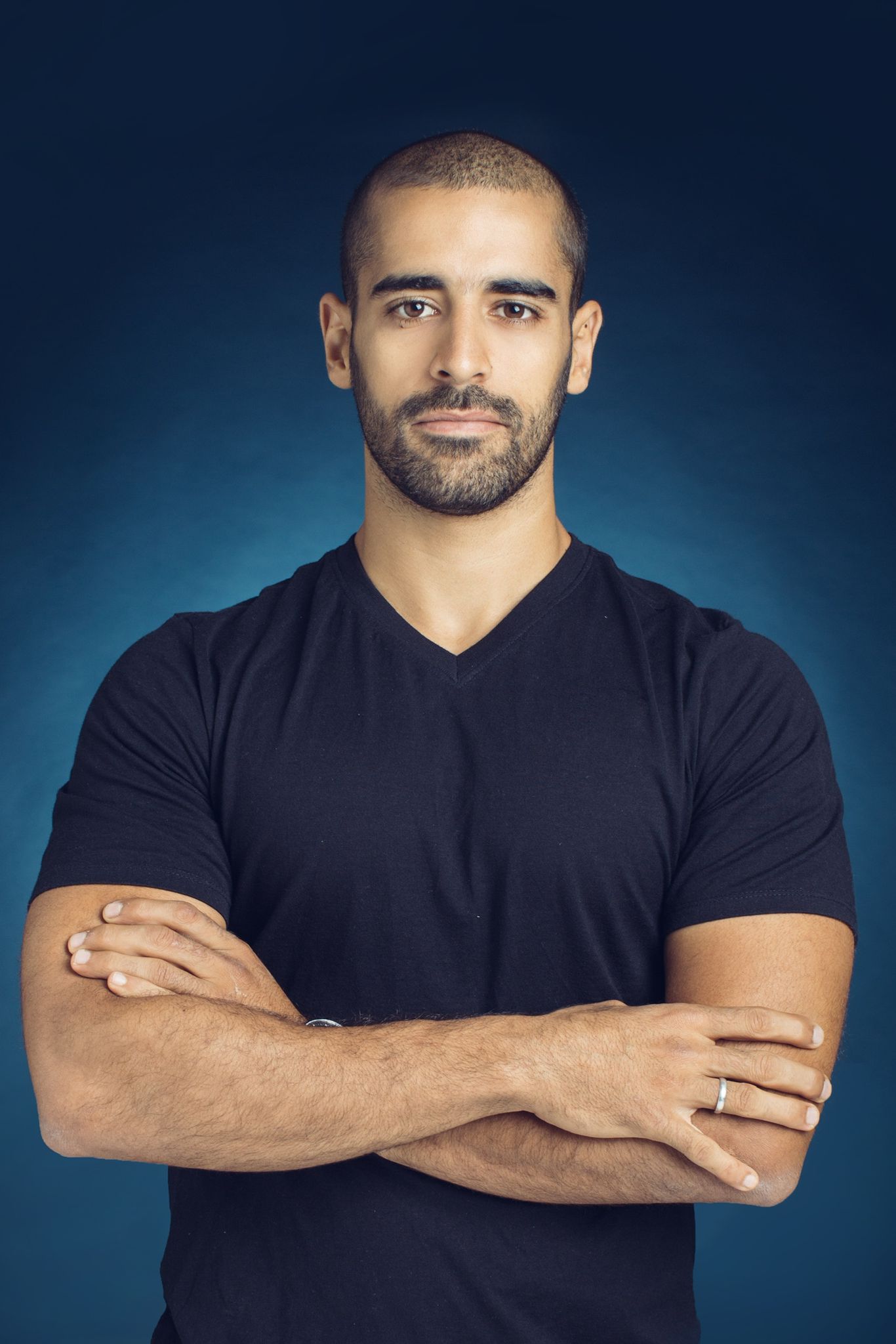

That morning, I met Abed Abu Shehadeh in a café tucked into one of the winding pedestrian pathways of Jaffa, an ancient port city on Israel’s Mediterranean coast. (Today, Jaffa is adjoined to Tel Aviv as part of what’s known as the Tel Aviv–Jaffa municipality.) Abu Shehadeh is a political activist, a former member of the Tel Aviv–Jaffa city council, and a lifelong resident of Jaffa. Since 2020, he has also hosted Al-Midan, a popular Arabic-language weekly podcast. (The title translates loosely to “city square.”) The show is produced by Arab48, a news outlet that was founded in the nineties, is now owned by the private Fadaat Media, and caters to Palestinians who live within the 1948 borders of Israel and make up roughly a fifth of the country’s population.

Jewish Israelis generally refer to this demographic as “Arab Israelis,” though many within the community, including Abu Shehadeh, prefer the term “Palestinian citizens of Israel.” Unlike Palestinians who live in the West Bank and Gaza, those in Israel hold Israeli passports and can vote in national and local elections. They also have their own set of political, economic, and social concerns. As in many aspects of daily life, from healthcare to housing, Israel’s Palestinian minority has long been both overlooked and underserved by the media. On Al-Midan, Abu Shehadeh digs into topics beyond the traditional realm of day-to-day news. “Of course there’s always politics,” he told me, “but I also try to go in depth on social issues.” Roughly 60 percent of the podcast’s downloads, which totaled around five thousand over the past month, come from within the 1948 borders of Israel.

The calm of the Tel Aviv morning would not hold. Hours after we met, two Palestinian men shot and killed seven civilians at a light rail station meters from where Abu Shehadeh and I had met. While paramedics tended to the wounded, air-raid sirens began to blast; Iran had launched more than a hundred and fifty ballistic missiles into Israel. Iran was retaliating, it said, for the recent assassination of Ismail Haniyeh, a leader of Hamas, in Tehran, and the bombardment of Beirut, during which the leader of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, was killed. Millions took cover in bomb shelters. A Palestinian man named Sameh al-Asali was killed by shrapnel from a missile in the West Bank.

Abu Shehadeh told me that, even in the moments of relative quiet, the war has stirred profound grief and anxiety among Palestinians in Israel. “People underestimate how important it is for Palestinians, what happens in Gaza,” he said. “It affects them.” In our conversation, we spoke about the challenges of being responsive in a time of crisis, the threats facing Palestinian journalists in Israel today, and the unlikely influence of Joe Rogan. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

YRG: What makes Arab48 different from other Arabic-language media outlets inside the 1948 borders of Israel?

AAS: There are a few local news websites, but Arab48 sees itself as being at the level of international outlets in terms of quality. You can feel this just by looking at the website: it’s clean, without pop-ups, without flashy advertising. There’s intensive fact-checking; the words are chosen very carefully. Many of the writers are professors and academics. But Arab48 is also a very ideological publication. If you ask our Arab rivals, they’ll tell you it’s a Tajammu publication. [Tajammu is a secular Palestinian political party] which advocates for a democratic state for all of its citizens. Because the party is secular and liberal, it’s one of the most serious projects that is challenging Zionism. Arab48 is not owned by the party, but this is the zeitgeist; we believe in democratic values not only here but across the Arab world.

Another thing that makes Arab48 very important is that we translate reports directly from Hebrew. The Arab world is usually three or four steps behind when it comes to Israeli media. We know Israel better than any other Arab group in the world, including research centers, because of our day-to-day interactions. So we have people [in the newsroom] whose job it is to read Israeli news reports. They don’t just translate word for word; they give credit to the reporter and add their own twist, take comments from an Arab parliamentarian or an Arab intellectual, and put the report in our words with our terminology.

What was your vision when you started Al-Midan? What did you want the podcast to offer that you weren’t seeing elsewhere?

I really appreciate long, detailed, deep conversations. I’m going to tell you what podcasts I listen to, and you’re not going to like it: I was introduced to the world of podcasts through Joe Rogan…

When you started with that preface, I had a feeling that’s what you were going to say.

The more well known he became, the more I understood about the problematic nature of Joe Rogan. But there are two things I really liked about this show. The first is the mixed martial arts [content]. More seriously: he brings scientists and academics on his show that I wouldn’t have access to otherwise. The thing I learned from Joe Rogan is that people want you to take something very complicated and just ask basic questions. I’ll give you an example: I had Mustafa Jarrar, a professor of artificial intelligence from Birzeit [a university in the West Bank], on the show, and we had a long conversation about AI being used in times of war. I asked him, Is AI going to take over the world? Of course, that’s a very childish question, but people think about that. He started laughing and explained why it won’t happen.

[With Al-Midan] I understood from the beginning that [Palestinian] discourse needs in-depth conversation, not only in politics. Until the war, Al-Midan’s most downloaded episode was about divorce in the Arab community. It went viral. I interviewed somebody from a criminal organization who loans money. I also interviewed an ex-junkie from a rehabilitation center. I went to these niches and it became very popular because we are lacking this discussion. Al-Midan is talking about more diverse topics and giving them more time.

Why was there a need for a podcast specifically geared toward Palestinian citizens of Israel?

Because we speak Arabic and Hebrew—and often also English—we are exposed to many different news outlets and sources of media. But we find problems with each one. If you look at the big podcasts in Arabic, like those from Al Jazeera, they’re very macro. Sometimes the hosts are not even Palestinian—they’re from the rest of the Arab world, and they don’t know the nuances of our reality. If you live here, you understand that what they’re saying is not always accurate. But then if you listen to [news podcasts in] Hebrew, even from left-wing outlets like Haaretz, you’ll be disappointed. They know the nuances and they might sound nice, but then in the first days of war, for example, they were pushing for the military to go into Gaza just like all of the other Israeli outlets. My view is that we need to be something in the middle. We have to give [the audience] this view of being part of the national Palestinian group. But we also have to give them the nuance that they’re looking for. When it comes to giving them details, it’s in their language and their terminology.

Why is the issue of terminology so significant in your work?

Language is everything. Israel really tries hard to disconnect us from the Palestinian cause, and the terminology plays a big role. I remember when I was on the city council, I was invited to talk to a group of Israelis who wanted me to explain what’s happening [within our community]. They didn’t have any problem with my analysis, but the only thing that bothered them was that I described us as Palestinians. They said, “You’re giving numbers, you’re giving facts, and we agree with your conclusion. But why do you have to say ‘Palestinian’? Why can’t you say ‘Arab Israeli’?” We believe in the existence of the national movement. When you say “Palestinians,” you’re saying, I’m Indigenous. I see myself as a part of a national movement, a part that has its own unique situation. When you say “Arab Israeli,” you’re disconnecting [Palestinian citizens of Israel] from this movement; it’s as if we immigrated here and don’t have any cultural, historical, or political background.

[Another] example: the Israeli media might [use the phrase] “terrorist attack.” We wouldn’t use the word “terrorist.” It’s not about [saying it’s] justified or unjustified, or about any moral or political acceptance. You just don’t use this word in Arabic. There’s a reason: because if you accept the terminology of the colonizer, you’re accepting the narrative they put forward. There have been incidents where people who were innocent were killed [by the IDF] and then labeled as terrorists. I don’t accept this narrative. We don’t know the facts, and often they will stop you from getting the facts.

There have been cases that I wanted to bring someone [on the show], but I couldn’t accept their discourse. Especially now, in times of genocide, I don’t think there is a place on my show for people who accept the Zionist narrative. It’s a safe space for us. I wouldn’t bring somebody on my podcast who describes us as “Arab Israelis,” for example. The terminology draws lines around who is with us and who is not.

CJR and other outlets have reported on the widespread crackdown on free expression by the Israeli government. For example, Tareq Taha, an editor at Arab48, was arrested for a story he posted on Instagram. Has this atmosphere affected your work, personally?

Absolutely. Arab48 sees itself as being a Palestinian outlet, but it’s not as straightforward as if it were in the West Bank; we have to be more careful [because we operate under Israeli law]. You always have to be one step ahead, thinking, If I say this thing, will this lead to indictment? Would this lead to prosecution? For two weeks after October 7, we didn’t publish anything. When we published again, we were careful with every single word. And there were guests who we invited but who said, We’re taking a break from media right now because we’re afraid that we could be prosecuted.

I think there are going to be more crackdowns—more serious ones than there have been so far—and I think people are underestimating how bad the situation is already. It’s like the analogy of the frog in the pan. If you put the frog in the pan and you boil it slowly, you’ll eventually cook the frog. I think we’re already cooking.

How has the war affected the topics you cover?

It’s much more political and much more oriented toward what’s happening with us [day to day]. I adapt. For example, this week I was going to record a podcast with a professor of urban planning. Then the war [in Lebanon] began. So now I’m recording a different podcast with a brilliant writer and scholar called Yaël Lerer. She’s Israeli, but she lives in France and speaks Arabic very well. [The episode is] covering how Israeli society is seeing the latest news coming from Lebanon and becoming more excited about full-scale war. It’s not that I’m covering the war in Lebanon; I’m giving the perspective that covering the war in Lebanon won’t give you. This is what I’ve been trying to do all through the war.

I’m getting very good feedback from people who appreciate that I’m sticking to the terminology, that I keep saying “genocide.” Others have stopped, and not enough people are talking about this. Something interesting happened about two weeks ago: the ratings are down everywhere; people don’t want to listen to news anymore. I think people are extremely exhausted, both Palestinians and Israelis. I think the economy is affecting people’s lives. People are feeling very stressed because of the war and where it’s going. At some point, people just want to disconnect and focus on themselves. I understand that, but I want to make it so that, in ten years when we want to see what happened, we have this material.

What would you want to tell journalists in other parts of the world about covering Palestinians citizens of Israel?

Very few people are getting it right [when it comes to] the complexity of covering Palestinians, especially citizens. There are two problems in general. One problem is over-romanticizing us by simplifying our identities, making us seem homogeneous, like we’re the ultimate victims. The other is dehumanizing us: as if Israel is doing us a favor for not kicking us out, as if Israel is not an apartheid state because we can vote. Both underestimate our ongoing struggle for communal rights. They don’t highlight our agency, our political discourse, our political ideology. People overlook [our movement] to build the state for all of its citizens.

Other notable stories:

- In yesterday’s newsletter, we noted internal tensions at CBS News following an interview in which Tony Dokoupil, a morning-show host, sharply challenged Ta-Nehisi Coates on a new book in which he is critical of Israel; following disquiet on the part of many staffers, executives ruled that the interview failed to meet the network’s standards, only for other staffers to complain that Dokoupil had been rebuked for doing journalism. Now the Wall Street Journal reports that Shari Redstone, the controlling shareholder of CBS’s parent company, has conveyed much the latter view to network bosses, though the Journal also reports that the incident was only “one of several that led management to criticize Dokoupil’s work” in a staff meeting (albeit without naming him). In any case, the LA Times reports that Dokoupil will not face any further disciplinary repercussions.

- Three new pieces from CJR: Ian Bassin and Maximillian Potter, of the nonprofit United to Protect Democracy, make the case that “despite the conventional wisdom that American media independence survived the tests of Trump’s first term,” he may already have succeeded in bending certain major media companies to his will. Elsewhere, the Tow Center, in partnership with Floodlight and ProPublica, reports on a “pink slime” newspaper in Ohio that has amplified a fossil-fuel industry campaign against a local solar-energy project. And Adam Piore examines consequential recent moves by Reuters and CNN to put up digital paywalls, noting that while many readers “don’t pay for the news they consume,” many others “are willing to do so, for the right price, and there is global demand.”

- In other media-business news, OpenAI struck yet another licensing deal with a major media company, Hearst; Sara Fischer reports, for Axios, that the deal will allow OpenAI to use content from Hearst titles to populate its products, in exchange for citations and (in all likelihood) a large payment. Fischer also reports that Fox News is set to debut a daily Spanish-language newscast via an existing sports network, and that it will also unveil a Spanish-language version of its website. And in the UK, Reach, a newspaper publisher, is reportedly pushing its journalists to write more articles—as many as eight per shift, in some cases—to boost traffic; Hold the Front Page has more details.

- This week, authorities in Russia said that they have opened criminal cases against fourteen foreign journalists who crossed into the country to report on Ukraine’s incursion into the region of Kursk; a Russian court issued extradition requests for two Italian journalists who covered the occupation, but Italian officials condemned the move. Meanwhile, the Committee to Protect Journalists called on Ukrainian authorities to investigate a series of recent attacks on reporters in that country. (We wrote about press freedom in Ukraine back in January, and the Kursk incursion in August.)

- And—after Don Beyer, a Democratic congressman in Virginia, declined to agree to any further election debates before November—Bentley Hensel, a software engineer and long-shot independent candidate in the race, is planning instead to debate an AI chatbot that he has trained on Beyer’s websites and press releases. (Hensel told Reuters that the chatbot is not intended to mislead voters.) Another independent has likewise agreed to the “debate.” The Republican candidate has not—and may also get the AI treatment.

ICYMI: A deadly year for a press at war

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.