Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Journalist Simeon Booker consistently broke barriers in a career that spanned more than 60 years. He was the first full-time black reporter for The Washington Post. He was the first black correspondent to cover the Vietnam War. He also covered 10 US presidents, from Dwight D. Eisenhower to George W. Bush (Take note, Jeopardy!). But it was during a five-decade long stint as Washington bureau chief for Jet and Ebony magazine that Booker was, to borrow from the title of his 2013 memoir, Shocking The Conscience of the nation—namely, through courageous field reporting that chronicled the seminal moments of the Civil Rights Movement. Booker died on December 10, in Solomons, Maryland. He was 99.

In hindsight, it’s easy to forget that the story of systemic racial inequality and oppression had to compete for headlines in the 1950s and 1960s. This was, after all, the era of the Cold War. The Cuban Missile Crisis. The Beatles. The Pill. And so, when it came to the daily reality of Jim Crow-style racism, public attention often waned. But that wasn’t so for the black press. In fact, Booker was among a dynamic cadre of unheralded reporters (dispatched by newspapers like The Amsterdam News, The Pittsburgh Courier, and The Chicago Defender) who consistently covered “the race beat.”

ICYMI: The bombshell Trump story published last summer that everyone missed

Yet it was Booker’s weekly dispatches—reporting on everything from the exploits of the Freedom Riders to acts of terror waged against black citizens in cities like Selma, Alabama—in the popular, pocket-sized Jet that resonated from the barbershop to the White House.

Today, Booker is rightly being remembered for his audacious coverage of the brutal 1955 lynching of 15-year-old Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi. It was so monumental, in fact, that other aspects to his remarkable career have been obscured.

Without question, we owe Booker and his peers a debt of gratitude for their service, both to our profession and this country.

To grasp 20th Century America, one has to weigh Booker’s work. At a time when black identity was partly forged by visible symbols of “those who made it,” photographs of Booker quizzing President John F. Kennedy carried their own power. And even though Booker enjoyed widespread respect (counting Martin Luther King Jr., Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy as close friends), he never hesitated to challenge those in power.

Richard Nixon would discover that lesson soon after being inaugurated in 1969. Despite a honeymoon with the Washington press corps, Booker called Nixon out for publicly courting the black vote while also waging a “Southern Strategy” that heightened racial hostility. (“You used gimmickry,” Booker scolded the incoming President. “You have allowed your men to divide….”)

Ironically, just a few years later, with America gripped by the Watergate scandal—which conjured up an endless assortment of characters—Booker chose to keep the spotlight on Frank Wills, the black security guard who discovered the June 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters.

Even though I’m also a journalist (a freelancer with bylines in The Daily Beast and Newsday), I knew nothing of Booker’s work for a long time. That all changed some two years ago when—as part of an independent research project—I found myself combing through vintage issues of Jet and Ebony. It occurred to me that Booker, like so many of his colleagues, had been largely overlooked for decades.

Fortunately, I had a chance to correct this historical oversight. As a member of the George Polk committee, which for more than six decades has honored enterprising journalism, I was privileged to have the support of my colleagues in recommending Booker for a career award in 2016. At a New York ceremony, which boasted attendees like Charlayne Hunter-Gault—a pioneering journalist in her own right—Booker received a sustained standing ovation when he appeared on stage. And the sheer magnitude of the moment was lost to no one.

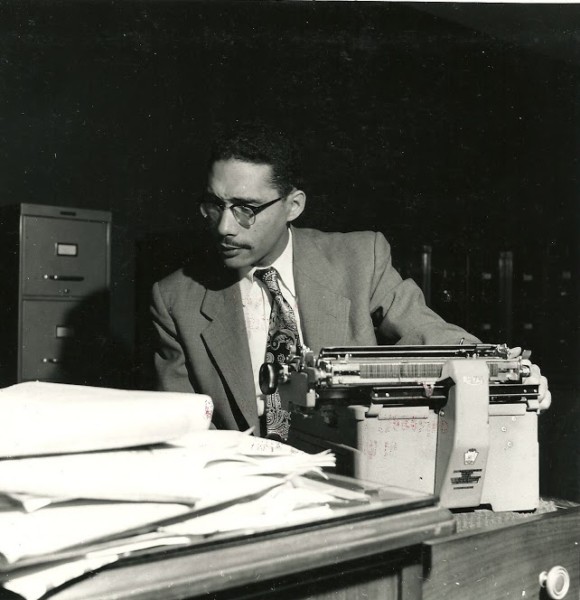

Journalist Curtis Stephen and Simeon Booker at the George Polk Awards ceremony in New York City in April 2016. Courtesy photo.

These days, as politicians deploy the term “fake news” in a clear attempt to intimate, one is reminded of the risks reporters like Booker faced while doing their jobs on American soil. His all-too-real legacy will endure whenever a journalist sheds light on something under-reported or speaks truth to power.

In 1966, when Jet photographer David Jackson died at just 44, Booker offered reflections that had long been true of himself and other pioneering black journalists at the time: “None ever won a Pulitzer Prize or got a major award. None ever will be mentioned in America’s journalistic Hall of Fame,” he wrote. “This group was the forerunner of the tremendous revolution….”

And in the decades since, they’ve been a source of pride and inspiration for many journalists—myself included. Without question, we owe Booker and his peers a debt of gratitude for their service, both to our profession and this country.

ICYMI: NYTimes editor apologizes after article sparks outrage

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.