Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Hillary Clinton’s question-and-answer session on Facebook this week received ample press, both positive (she’s communicating directly with voters!) and negative (this is about show, not substance). The coverage echoes sentiments that have circulated since digital town halls started becoming an expected part of political campaigns. But because Clinton has kept her distance from reporters–who’ve been gnawing at the bit to ask her, well, anything–her participation in this event has been given the tone of a watershed moment. Are digital town halls valuable new tools for journalists who can’t otherwise reach politicians?

The short answer? No.

The purpose of Clinton’s Facebook Q&A–as is likely true for every other digital town hall–was to charm current and would-be supporters. Of the 12 questions Clinton answered, four did come from the Fourth Estate. (The event generated more than 4,300 comments, by media and non-media members alike.) Some of her answers merited attention, but, overall, her selection of questions was unsurprising.

Reporters pried at her thoughts on Republican Senator Mitch McConnell and the “gender card,” capital gains taxes, and flexible benefits for “gig economy” workers. Clinton’s responses: McConnell is out of touch, capital gains taxes should be reformed to foster long-term investments, and Uber drivers are important, but we’ll tackle that one later.

This is not the way a candidate should be dealing with the press.

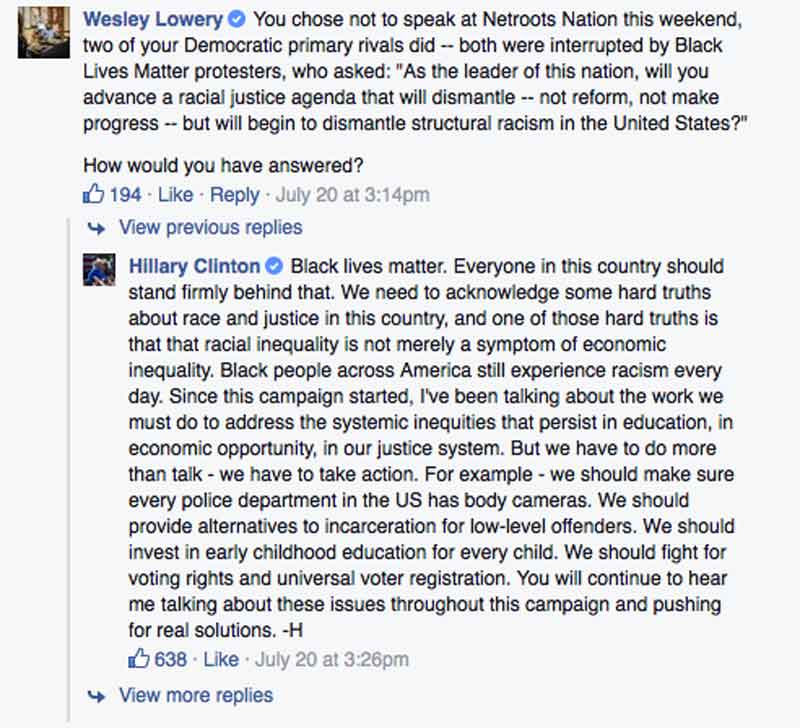

Some journalists do find use in digital town halls. “The role of the press in the political process is changing, and we still have to figure out what the best way is to insert ourselves and to extract meaningful information and meaningful answers,” says the Washington Post’s Wesley Lowery, who was one of the lucky few to get a response from Clinton. “Sometimes it may seem a little hokey, but at the end of the day, if we’re getting a response from the candidate directly on the record to a question you’re asking, it’s always a net positive.”

The chances of getting a question answered, though, are slight, and there’s a strategy to crafting questions designed for the digital space. At press conferences, politicians can be selective about who they call on, but they don’t know what reporters will ask them. If it’s a question they don’t want to answer, they can deflect, but that deflection is on the record. Online, politicians choose precisely which questions they’ll answer. That means if you’re a reporter, you don’t want to throw softballs, but you also can’t ask anything too tough. Politicians get off easy here because nobody actually expects them to jump into thorny, and potentially damaging, issues on their own turf.

Lowery’s question centered on structural racism, a topic that proved tricky for Clinton’s opponents during a weekend conference she didn’t attend. He deliberately crafted a neutral post he considered neither a softball nor leading, hoping to gently nudge the campaign to respond.

Although Clinton and her aides had the benefit of hindsight and physical distance, her reply proved telling–and somewhat surprising–to Lowery, who covers criminal justice, race, and politics.

Digital town halls are advertised as casual chats with constituents, but in reality they more closely resemble press releases. The Huffington Post’s Alexander Howard, who also received an answer from Clinton, says that’s a concern for reporters. Largely lost on the digital campaign trail is room for the politician to break from the constructed message, he says.

This all means journalists must sometimes settle for vague answers that wouldn’t land at press conferences. Follow-ups typically go unacknowledged online, where there isn’t a press corps to keep the issue afloat. The exchange, governed by the rules of the internet, simply doesn’t stack up to in-person reporting. “This is great, but it’s totally no substitute for regular press availability,” says Philip Rucker, a national political reporter who has been with the Washington Post for 10 years. “This is not the way a candidate should be dealing with the press.”

Political reporters already live this realm, tailing candidates who are waging meaty, demographics-driven campaigns across websites and apps, Rucker adds. But while the physical trail is still king, journalists lose when they write off the digital stump.

Plus, it’s also a chance for reporters to chew the fat with thousands of potential readers. After all, people come to these virtual Q&As because they’re happy to finally have a voice, says Scott Talan, a former municipal politician and reporter who’s now a social media expert in American University’s communications department. In the Clinton case, the public asked questions about student debt, immigration, pantsuits, and what it’s like to be a grandmother. “Now these are not what you would traditionally consider presidential issues, or ‘serious’ ones,” Talan says. “But to the people asking the questions … this is important.” That’s a lesson the media might be wise to carry home.

So what’s the takeaway? Journalists can’t avoid these brief, manufactured online interactions, but they also shouldn’t settle for them. There’s no replacement for regular press access, and until politicians agree to communicate with the press on even ground, they aren’t saying nearly enough.

(Clinton’s campaign was reached for comment, but a spokesperson did not respond to questions before this article was published.)

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.