Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

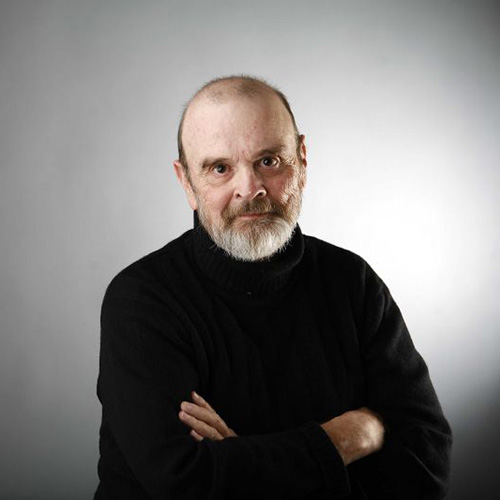

After 33 years and roughly 8,700 deadlines, the San Francisco Chronicle daily columnist Jon Carroll bid his readers farewell in the days before Thanksgiving. The 72-year-old occupied a role that’s receding from regional newspapers. Published Tuesday through Friday in the Chronicle’s entertainment section, Carroll was beloved by many for his irreverent sense of humor, his candor, and his unabated curiosity about Bay Area life. He spoke with CJR over the phone on Saturday from his home in Berkeley. The following is an edited transcript.

Writing a daily column for so long sounds exhausting.

It didn’t seem to be at the time. Call me back in three months and we’ll see if it was draining. I haven’t written not on deadline since 1973. I’m always on deadline, so the question is what it’s like off deadline. I don’t know! Maybe I’ve depended on it for adrenaline all these years.

Mentally, were you in column mode for 33 years?

It was very odd because I would go out to have fun, and I would have fun, I would. But occasionally, I would think back to what I had to do the next day, and I would worry over the problem areas of the next column. There are always four paragraphs that are just the sucky ones, and you have to figure out what to do about them. My wife got to the point where she’d look at me and say, You’re writing, aren’t you?

This Sunday in the middle of the afternoon I thought, Oh my God! I don’t have a column idea. Then I thought, Oh, I don’t have to, I’m retired! That really made me feel a lot better right away. There’s kind of a tension and release that happens almost daily, and it can be stressful.

Why did you decide to retire?

It’s a complicated question. Let me put it this way, it was not entirely voluntary, but I was offered a choice and I took it. I have to say that now that it’s happened, I couldn’t be happier. Let’s put it this way: All of the features of corporate bureaucracy have come to dominate the newspaper business, which used to work on a slightly more informal basis. It wasn’t like a factory.

How well could a faithful reader actually know you?

The personal stuff I write is true: I do have two daughters, I do have two granddaughters. So they know all that, and they know about my cat and they know that my wife wants to get a dog but I don’t want to. That’s all real, and the reason you do it is that lots of people relate to it. When you write about your family, you’re writing about their family. It’s recognizable if it’s part of the common experience.

Like every human, I have all sorts of secrets. I have all sorts of stuff I’ve never discussed in the column. As an example that’s now moot, my mother went through a very hard time for a very long time with various ailments. In her latter years she had something called Post-Polio Syndrome, which mimics what Polio is like. She absolutely did not want me to write about her, despite the fact that many of my peers were dealing with aging parents. So I didn’t. You respect what somebody wants and you don’t write about it, even though it takes up a lot of your consciousness. On a lighter note, when my daughters were dating, they absolutely did not want any stories about them. I couldn’t touch it.

Do you think strangers you met wondered if they’d become part of your next column?

They all did. A lot of my friends started out in one way or another as professional contacts. But I always would say that this is off the record or my notebook is in my pocket, so there was enough awareness that it was fine. When in doubt, I’d ask, and there was never a complaint. My daughter complained once a year, and that was it.

The day he retired, Carroll wrote to the “Dear Abby” advice columnist asking for counsel on this topic:

Abby: I have been a San Francisco Chronicle columnist for 33 years, and my picture is at the top of the column. Because that enables readers to recognize me, I have had to leave lavish tips in the jars on the counters of cafes and coffee shops. Now that I am retiring, do I still have to be generous? —Wondering in Oakland

Dear Wondering in Oakland: Only if you plan to continue eating in those establishments. Your celebrity status carries with it extra responsibilities. So live with it—and enjoy it!

How did you decide what to keep private?

First of all, my guideline was if it involved other people directly, I wasn’t going to touch it, and even asking was a violation. But in terms of myself, it was incredibly scary. One of the ways of knowing what’s going to work is asking what scares you to write about. And the other one is, Is this likely to do somebody any good if I share this? Are other people going to relate to it? When I wrote about my large bout with depression, it was just one column, and it was basically a description. [Note: Carroll wrote that column in 2014, following Robin Williams’ suicide.] It wasn’t a prescription; it didn’t say, Go do this. It was like, here’s what it’s like to be depressed. And a lot of people said that it expressed for them what they could not tell their families about how they were feeling. Patients would come in and give the column to therapists, I heard. It helped a lot of people, and I’m very gratified that that’s true. Never written about it again. Not once, because it was really scary.

When it comes to negative feedback, every young journalist learns to cope with brutal online comments.

Don’t read them. I haven’t read them for 15 years. I got on the internet very early. [Note: Carroll first went online in 1987, “just to write a column about it.”] I was already familiar with trolls and assholes who populate the internet, and after a year of reading them when comment sections launched, I said, No thank you.

You’re not on Twitter, right?

I am, but I don’t post much. Twitter does not satisfy my social media needs. It really doesn’t. I find it very difficult to have any kind of conversation on Twitter, it’s just post, post, post, post. I do post on Facebook because it at least allows more than 140 characters.

Do you have much interest in Twitter and Facebook as journalism tools?

No. The social media platform I started on was called the Well. It exists today, and it’s for people who want conversations, sometimes very vigorously.

Some journalists who write first-person essays like you see Twitter as a useful platform for every stray thought.

The trouble with my stray thoughts is sometimes they’re not very good. I know because it is my business to write down stray thoughts, but it’s also my business to examine those thoughts 24 hours later and decide that three-quarters of them are bullshit. So I would hate to have every stray thought go out there because I don’t even believe half of them.

Facile writers can get confused as to what their opinion is by how well they write it now. If you come up with a great sentence that bends your actual beliefs a little bit, then you’ve got a great tweet. A lot of this chatter is between people who are producing their actual work somewhere else. And I am more interested in people’s actual work than in their Twitter work. Mostly, I think Twitter is used by people who are trying to stir up interest in themselves or interest in their ideas by doing this kind of billboarding thing.

A lot might have to do with building a so-called personal brand.

Long before they were called brands—a word I hate, by the way—there were star journalists and star photographers. Margaret Bourke-White, for godsakes. Ernest bloody Hemingway, who was a star reporter from Spain. The cult of personalities existed as long as journalism. There was a time when editorial cartoonists had enormous cults of personality. I’m not sure how successful you can be developing a brand that’s totally not who you are, but I didn’t, I just wrote as myself. It was assumed that you would hire colorful characters, and they would do colorful things. I guess I was considered a colorful character. I was wearing long white shirts and beads far after anybody else was.

How do you decide if a stray thought is column-worthy?

I try to write the lede sentence in my head of whatever the column would be. Then I write the second sentence, and I see if there’s still anything there; if I can have a nice four or five-paragraph description of that idea. I make all these judgments, and at some point you say, Well, do I actually believe this? That’s how you test it. You winnow it by trying to write it.

Where do you do most of your writing?

I’m very much in favor of writing at home. That was one of the issues with the Chronicle and me. For 25 years I’d write at home, and the idea that it would be useful for me to write somewhere else is nonsense. Particularly in the Bay Area, which has insane traffic, why would you want to get in a car and drive 30 miles in the worst traffic in the nation across the Bay Bridge, pay for parking, worry about your clothes and if you’re wearing the same thing as yesterday because that would be tacky, and pay for your lunch rather than make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for 58 cents.

When I was at a newsroom, being out of the office was considered to be a good thing, absorbing whatever it is you were supposed to be absorbing.

Any advice for up-and-coming journalists?

The first one is tell the truth. Find out what you really think about something. There are so many familiar paths that you can take about anything. Try to rethink the entire thing from the beginning.

If you’re doing personal columns, never give yourself a good line because then you seem self-aggrandizing. But if you’re clueless or the butt of the jokes, then you’re telling a story. The reason to tell domestic stories is that that which is most common is most universal. The biggest compliment is when I write about my daughters, and then someone writes me a letter about their kids.

What about writing a daily column for all those years was most gratifying?

I would say there were two things. If you get that much freedom to write, and if you write for as long as I did, you get to have moments of just absolute crystal enjoyment and pride in your own work. It happens maybe once a year when you can look at a column and say, Well, that was a pretty good fucking column. That’s professional pride, and I don’t know that writers talk about that very much. Secondly, there’s a relationship with the readers, which I am going to miss. It was a lot of fun to hear that call and response kind of thing. It’s clearly a significant part of the job you do. There are columnists who don’t take that seriously at all. Any reader who’s presenting me with an idea, I’ll enjoy. It’s like having a bunch of strangers whom you’ll never meet in person but with whom you’ve had a conversation over 15, 20 years—almost like you’ve been to Thanksgiving at their house 200 times, but only for five minutes at a time.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.