In the winter of 1907, Denver showed the rest of the nation how to fight a newspaper war. The Rocky Mountain News published an editorial alleging that Frederick Bonfils, the co-owner of The Denver Post, was a blackmailing rogue who used his paper to smear those merchants with the temerity to advertise in rival publications. Bonfils, gravely offended, decided the only reasonable response was to sneak up behind the News’s elderly publisher, Senator Thomas Patterson, and punch him repeatedly in the head. He did so in broad daylight, and as Patterson lay dazed in a weedy downtown lot, Bonfils stood above him, howling about the pain he would inflict if his name ever again appeared in the News. It was December 26: Boxing Day.

Three days later, Bonfils was arraigned for assault and battery, but the prosecutor tried the case as if the Post itself were under indictment. Patterson testified to the Post’s vicious, retaliatory business practices, and decried its many offenses against journalism. “I have had no question in the world but that Mr. Bonfils and Mr. Tammen have used the paper that they control for blackmailing purposes,” declared Patterson. The courtroom burst into applause.

Gene Fowler tells this story halfway through Timber Line, his riotous anecdotal history of the Post’s early years, and by then it’s clear Senator Patterson wasn’t the only Denverite who had been floored by the Post’s editorial leadership. Bonfils and his partner, Harry Tammen, purchased the newspaper in 1895. Over the next 12 years, through a mixture of gimmickry, hustle, bad faith, and criminal mischief, they built it into the dominant newspaper in Colorado, with a readership that eclipsed the combined circulation of its three closest competitors. A pandering, schizoid broadsheet that put the “yell” in “yellow journalism,” the Post was the newspaper the people of Denver wanted, though perhaps not the one they deserved.

Timber Line is a story about the most scandalous newspaper of its generation, and how its badness made it legendary. The Post pioneered the concept of the guilty-pleasure read. It took the yellow journalism popularized by Eastern papers like The New York World, made it half as smart and twice as loud, and refused to apologize for doing so. Every evening, the Post arrived as if shot from the barrel of a Remington revolver, aimed directly at whoever stood in its publishers’ way. Subtlety and moderation were foreign concepts. When an outlaw rides into town, he lets everyone know he’s there.

Today’s newspapers, losing ground to Internet outlets that are less thoughtful, less serious, and infinitely more popular, can perhaps empathize with the Post’s rivals, who fumed as the public rushed to embrace this lunatic newcomer. It’s not always clear what to do when faced with a competitor who plays by different rules, and so it’s understandable that the spectators in the Denver courtroom that winter’s day were enthusiastic about what appeared to be a chance to restore order to the city and hold the Post accountable for its crimes.

It didn’t work. The judge fined Bonfils $50 plus court costs, and left him and Patterson with some words of advice: “If you desire to place this community under a deep debt of gratitude, you can easily do so by placing in the columns of your great newspapers matters more beneficial to the community and interesting to the readers” than had lately been appearing. But Bonfils knew more about what the great mass of people in Denver wanted than did their senators and judges. The lecture went unheeded. Bonfils and the Post were just getting started.

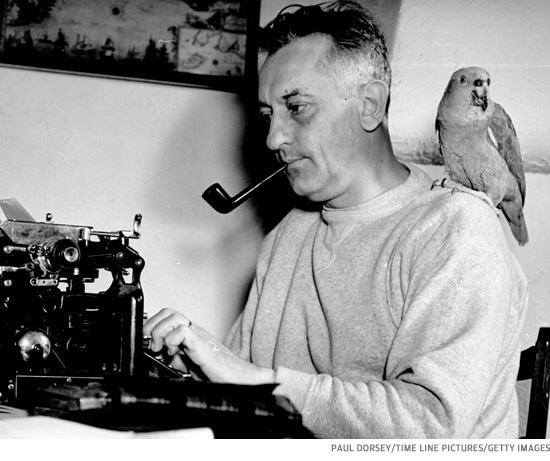

Gene Fowler worked at the Post from 1914 to 1918, covering sports and writing features. A newsroom wit like his contemporaries Damon Runyon and Ben Hecht, Fowler fit a journalistic archetype that has been professionalized out of existence today. Various biographies are filled with stories of the boisterous, carousing Fowler blowing deadlines, devising pranks, and antagonizing his interviewees with impudent questions. (In his first month on the job, he so offended Buffalo Bill Cody that Cody tried to have him fired.)

He got away with it because he could write. Though wholly forgotten today, Fowler was considered one of the best journalistic storytellers of his generation. In his books, at least, he worked in the realm between fact and fiction, drawing vivid, big-hearted portraits of larger-than-life characters. Fowler did his reporting, then he buffed the truth into legend.

In 1933, Fowler took the stories he had collected during his time with the Post and worked them into Timber Line, an absurdly entertaining and mostly true tale of the rise of the most outrageous newspaper in the West. (The book’s title refers to the point of elevation above which trees cannot grow—an apt metaphor for the Post’s hazardous and breathtaking history.) Structured chronologically, told anecdotally, the book covers the period between Bonfils and Tammen’s purchase of the Post and Bonfils’ death 38 years later. But the story Fowler tells is grounded in the region that birthed it.

While most people came to Colorado with picks and pans and dreams of striking gold, William Byers came toting a printing press. In 1859, he unpacked it in the small mining settlement that would become Denver; the city and the Rocky Mountain News were founded almost simultaneously. Other newspapers followed—The Denver Tribune, The Denver Times, dozens of weeklies and monthlies. In Voice of Empire, William Hornby describes how the city’s dailies were tied to entrenched political and business interests. They were published by respectable men who ran their papers the way Eastern publishers did: to influence and serve the power elite.

They were writing for a limited audience. By the end of the century, Denver had more than 100,000 residents, mostly provincial types who, though they may have been interested in politics, were never going to be active participants in it. The citizens of Denver spent their days laboring at jobs that were dangerous and often deadly. Their leisure hours were spent chasing carnal and spiritual intoxicants. And while Denver’s papers promoted the city as a mountain oasis, with fine cultural amenities and the healthiest climate in the country, the reality was somewhat different. In Queen City, his excellent history of the city’s early years, Lyle W. Dorsett describes late-19th-century Denver as “crude, dirty, disorganized, expensive, and culturally deprived,” with sooty skies and muddy, malodorous streets trod by drunkards, juvenile delinquents, and aggressive packs of wild dogs. Henry Doherty, a crooked utilities baron forced to flee the city in 1906, put it succinctly: “Denver has more sunshine and sons of bitches than any place in the country.” Fred Bonfils and Harry Tammen were two of the biggest. And in founding a paper by and for the sons of bitches, they struck gold.

Tammen came to Denver as a bartender, but soon found more lucrative employ peddling ersatz arrowheads and Western curios by mail order. He did so in the pages of a magazine-cum-catalog called The Great Divide, in which trinket sales were stoked by romantic, mostly apocryphal stories of the heroes and horrors of the Wild West. Bonfils, for his part, came to Denver after having been chased from Missouri for running a rigged lottery in which he and his confederates always ended up winning the biggest prizes. A West Point dropout who claimed kinship to Napoleon, Bonfils built his fortune one swindle at a time. (When land in Oklahoma City was at its peak, Bonfils sold lots there at one-third the market value. He neglected to mention the lots were located in Oklahoma City, Texas.)

Fowler has great fun drawing contrasts between the two very different partners, who resemble a power-mad Laurel and Hardy. Tammen, energetic and glib, cultivated an image as a lovable scoundrel; Bonfils, brooding and dyspeptic, loved dogs and money and not much else. God only knows why they decided to go into the news business. Neither was particularly interested in journalism, civic activism, or even reading. (One historian suggests that Bonfils was barely literate when he purchased the Post.) They were hustlers and con men, and the paper they created reflected that. As Fowler tells it: “From this friendship was born a blatantly new journalism, called by some a menace, a font of indecency, a nuptial flight of vulgarity and sensationalism; by others regarded as a guarantee against corporate banditry, a championing of virtue and a voice of the exploited working man. The important thing was that everyone would have some opinion of the product of this union.”

Bonfils and Tammen set about advertising the Post with tricks and gimmicks better suited to a traveling circus. (Later, Tammen actually purchased a traveling circus, and used the pages of the Post to build its business by viciously defaming its rivals.) They installed a gigantic, electric American flag outside the newsroom, and a siren on the roof. Pedestrians near the Post office would sometimes see Bonfils, “a sudden wild gleam in his eye, prancing on the balcony, reaching into cloth sacks and pulling out fistfuls of new pennies, flinging them to fighting gamins below and shouting: ‘Lucky! Lucky! The Post brings you luck!’”

The paper itself became a tribute to excess. It ran the biggest headlines, hired the loudest newsboys. It bought every comic strip and syndicated feature available, in order to keep them out of the hands of its rivals. Bonfils and Tammen staffed the paper with big names (Frederick W. White, the essayist and drama critic), fancy names (Lord Ogilvy, youngest son of the Earl of Airlie, who became their farm reporter), and funny names (sports editor Otto Floto, who was hired because Tammen found his name delightfully musical). They brought in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s son for a month, paid him $1,000, and published none of his stories, instead selling his best work elsewhere for a $2,500 fee.

All this sound and fury helped the Post court the emerging readers whom Denver’s other newspapers had theretofore ignored. Populist when it was expedient, provincial by default, the Post promoted itself as “The Best Friend the People Ever Had.” “Write the news for all of the people,” Bonfils once instructed his reporters, “not just the rich and important or those who think they are. If you are understood by the busy, simple folk, everybody will understand you.” When a Post copyeditor balked at an ungrammatical headline reading JEALOUS GUN-GAL PLUGS HER LOVER LOW, Tammen refused to budge. “That’s the trouble with this paper—too God damned much grammar,” he said. It was less a retort than a statement of purpose.

The Post specialized in crusades and investigations, choosing its targets for maximum shock value and maximum financial benefit. When local coal dealers failed to advertise in the Post, Bonfils and Tammen leased their own coal mines and undercut their competitors’ prices, printing stories all the while that bashed the piratical “coal trusts.” When local retailers banded together to withhold their advertising, the paper retaliated with a series on how Denver’s department stores routinely violated child labor laws. (The retailers soon reconsidered their boycott.)

Crime was a popular topic. “When attacked in pulpits or women’s clubs on the ground of sensationalism, of catering to the mass moronic mind by playing up crime and criminals, the Post owners said they did this to show that ‘Crime doesn’t pay,’” writes Fowler. “They sprinkled little black-face lines of type throughout the paper, usually closing a tale of morbidity with the grace note: ‘Crime never pays.’” (The Post’s use of typography was consistently creative, deploying huge headlines, numerous fonts, and blood-red ink whenever something required extra emphasis. John Gunther, a latter-day observer, once compared its front page to “a confused and bloody railway accident.”)

The two men behaved like no publishers the city—any city—had ever seen. While Tammen spent his time “blowing gigantic tubas and belaboring gargantuan kettle drums up and down the streets to impress the public, and thinking up such eight-column headlines as: DOES IT HURT TO BE BORN?,” Bonfils kept his eye on the budget and rigged Post contests so that he would win them. Tammen and Bonfils shared an office, a large upstairs room called the Bucket of Blood, both for its garish, plum-red walls, and because Bonfils was once shot through the throat there by an aggrieved attorney. “On Bonfils’ desk was a globe of the world, at which he often gazed with a proprietary stare,” notes Fowler. “Within his reach was a sawed-off shotgun.”

As Denver grew, so did the Post’s circulation. Unable to compete on newsstands, finding no justice in court, the Post’s competitors could do little but complain in their editorial sections. In the words of the Boulder Camera: “The truth is that the Post is daily a disgrace to journalism. Its policy is for the corruption of the morals of the state. It has raised the black flag of the buccaneer concealed beneath the folds of the American flag.”

Modern readers, accustomed to even the most vulgar publications maintaining a certain level of decorum, may find it hard to imagine that a newspaper like the Post ever existed. Did Bonfils and Tammen really hire a vaudeville performer to hold a fork in his teeth and use it to spear a turnip that had been thrown from the 12th floor of a building? Did they really strap a giant electric crucifix to the belly of an airplane and have it flown over Denver each Christmas eve? Were they really so brazen about threatening those who didn’t advertise with them? Did Tammen really respond to a contempt-of-court charge by storming into the courtroom and angrily informing the judge that, though it might take 20 years, he’d have his revenge?

Modern readers also will find it difficult to gauge how bad a paper the Post really was. There are times in the book when it seems like the worst newspaper on earth. As one contemporary of Fowler’s put it, the paper was “loaded with silliness posing as wisdom, broad inconsistencies that wouldn’t fool a prairie dog, and bold statements that a certified idiot wouldn’t believe.” But Fowler occasionally defends the Post. No matter why the paper’s crusades were launched, he notes, the people being targeted were generally guilty of the crimes of which they were accused.

In Timber Line it is often hard to tell what is real, what is embellished, and what is invented. The book is neither footnoted nor heavily sourced, and there are lots of quotes that seem improbable. Though I suspect that one could plumb the Post’s archives and confirm most of what Fowler cites as fact, many of the Tammen stories seem drawn from memory rather than transcripts. In Voice of Empire, William Hornby reports Fowler’s admission that he “did not let history get too much in the way of a good story.”

It doesn’t matter. The book is very funny, at times very moving, and for today’s purposes it’s probably accurate enough. Fowler writes romantically and sentimentally about the West and the news business, both of which attracted overgrown boys fond of pranks and stunts and seeing what one could get away with; he writes of newspapering as the last, best profession for those who wouldn’t, or couldn’t, flourish elsewhere. He makes the Post seem more delightful than any paper devoted to hoopla and brigandry has a right to seem.

Timber Line is not, however, particularly focused. (This is clear from the first chapter, a tenuously thematic seven-page anecdote about a mischievous burro Fowler owned as a child.) As the Post was not a particularly focused newspaper, these digressions seem fitting. But they also can be confusing, and at times it seems that Fowler let his wild, wooly subject get away from him. He devotes three long chapters to individuals who lived in Colorado but were wholly unaffiliated with the Post: Margaret “Molly” Brown, a wealthy miner’s wife who was famously dubbed “unsinkable” after surviving the Titanic; Tom Horn, an Indian fighter and hired killer; and Alferd Packer, a trail guide and cannibal who survived a vicious mountain winter by killing and eating his traveling companions. The stories are entertaining—particularly the Tom Horn chapter, which might be the best thing in the book—but they have little to do with the Post, besides a vague “look at these things that also happened in the West.”

But subsequent reads suggest the digressions are there for a reason. Timber Line is nominally about the Post, but it’s mostly about the Post as a product and reflection of its time and place, about how it embodied and reflected the flaws and virtues of the frontier. The American West of popular myth is a land of the defiant. Its great figures share a reckless, near-delusional intransigence that seemed to lead them in equal measure to glory or the gallows. Back East, men like Horn would have been ostracized, or declared insane. In the West, insanity was a survival tactic.

The Post’s near-lunatic defiance of accepted norms and standards is what made it great, Fowler argues. He presents Bonfils and Tammen as Western antiheroes in the same legendary vein as Horn, Packer, and the rest. The Post and its owners were cut from the same material, Fowler is saying, and ought to be remembered right alongside the other entities whose antics defined the West; the Post deserves to be mythologized as a newspaper that, for better or for worse, defined its time.

But times change, and legends fade. In Voice of Empire, William Hornby suggests the Post succeeded by appealing to the “populist tastes of a growing mass reading public that was then unentertained by any broadcast sirens.” As movies and radio emerged, the ordinary people found other means of titillation. Today, Timber Line is out of print, Fowler is forgotten, and The Denver Post survives as a competent, professional daily newspaper with a coherent typographical scheme, carrying no trace of its lurid past.

In 1932, Bonfils was brought to trial again, this time for contempt of court. Tammen had died some years earlier, and Bonfils, left alone, had stumbled. He sued the Rocky Mountain News for libel, and when called to give a deposition, he refused to answer several personal questions, thus earning the contempt charge. This time around, the News sent Bonfils sprawling. The paper filed a petition listing Bonfils’ crimes: contract fraud, political bribery, stock manipulation, unsportsmanlike behavior on fishing trips. It was extensively documented, and it was too much for Bonfils to handle. He died unexpectedly in February 1933, of an ear infection, having never answered the charges brought against him. COLORADO HAS LOST ITS GREATEST CITIZEN was the Post headline.

Timber Line came out later that year. By then, Fowler, who had left Denver in 1918 for newspaper work in New York, had moved to California. Some say that he wrote the book hoping it would be turned into a movie, but that never happened; perhaps Tammen and Bonfils were too outlandish even for Hollywood.

Still, Fowler became one of the highest-paid screenwriters of the era, and befriended the likes of W. C. Fields and the Barrymores. When he died, in 1960, his famous friends contributed reminiscences to a pamphlet paying tribute to his life and legend. In it, you can detect ambivalence toward the movie business: “Occasionally Fowler found himself pressed for cash, though he had made fortunes during his career. At these times, he went to work for the movies, driving down early each morning and taking up the ridiculous stance in one of the overdressed cubicles, poised, always, for a ‘conference.’ But before he started the drive, he customarily threw up, out of distaste for the day’s nonsense to come.” Hollywood was run by the sort of people who attacked one another behind closed doors, and I can’t imagine Fowler ever felt completely comfortable there.

When he first came to New York, Fowler lived in an apartment on Amsterdam Avenue, right down the street from Columbia University. The apartment looks out at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine—the largest cathedral in the world, a mad, ambitious attempt to outdo the Gothic churches of Europe. One hundred and twenty years after construction began, the cathedral remains unfinished, like a stunt suspended in time.

Now and then, when work is slow, I will sit on the cathedral’s steps and eat lunch in its ludicrous shadow. I picture Fowler doing the same thing 100 years ago. And I wonder if, sitting there, he too was reminded of Bonfils and Tammen and the time before subtlety, when glory lay in the regions where most men dared not go, somewhere up beyond timber line.

Justin Peters is editor-at-large of the Columbia Journalism Review.