No Depression published its first print magazine in 1995, thanks to a small but loyal community of people who had first gathered online. Founding editors Grant Alden, then an editor of Seattle’s Rocket biweekly and an expert on the city’s grunge scene, and Peter Blackstock, an Austin native who had just moved to Seattle to write a column for the daily Post-Intelligencer, shared an interest in bands like the Bad Livers and Jason and the Scorchers, who didn’t fit neatly into any existing genre.

Blackstock occasionally participated in an online message board called NoDepression.AltCountry, named for the 1993 debut album of Midwest alt-country group Uncle Tupelo (who had, in turn, named their inaugural recording, No Depression, for a song The Carter Family had recorded a half-century earlier, during the Great Depression). Blackstock and Alden believed that alt-country’s rich and emerging lineage demanded studious consideration in print. Their magazine, No Depression, would be guided by the long story of American roots music, and would prioritize longform journalism in a way few music publications had before. For 13 years, No Depression legitimized a growing community of niche musicians, first as a quarterly and eventually as a bimonthly.

Related: A new digital magazine forces you to unplug from the internet

The magazine’s committed staff of critics, feature writers, and editors took the music so seriously that the world started to follow suit. Alt-country, and the roots and Americana music into which it evolved, took over the airwaves. No Depression’s relationship with retail chains like Tower Records got the magazine distributed worldwide. At its height, No Depression had a subscriber base of 15,000 readers and printed 40,000 copies of each issue.

Then came the 2008 recession, and with it went the ad revenue—mostly from independent record labels—that had kept No Depression above water. To boot, Tower Records and numerous other retail chains that carried the publication from the beginning began to shutter. Alden and Blackstock, along with ad sales manager Kyla Fairchild, decided to take the magazine out of print that spring—one in a long string of independent magazines that would cease print operations that year.

Yet, subscriptions had trended up even through the final issue, and the readership was so loyal it referred to the niche genre as “No Depression Music.” With the Americana Music Association gaining ground and the soundtrack of O Brother Where Art Thou? attracting new fans to the genre, No Depression was well-positioned to speak with authority about where this music had come from and where it might be headed.

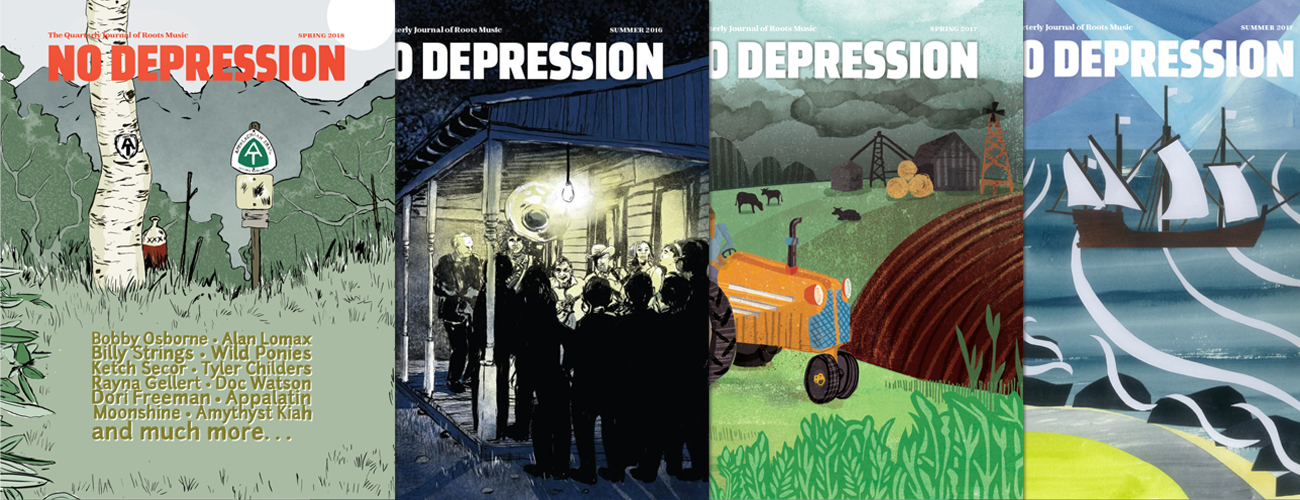

Now, nearly a decade later, No Depression has emerged with a hefty quarterly journal, free of ads and full of longform music journalism reported by paid freelancers—a rare feat in post-recession publishing, and one that other niche journals and regional publications might learn from.

The new NoDepression.com launched in the fall of 2008, and Fairchild eventually brought all 75 issues of the print magazine into a separate online archive. Initially, the online magazine was just that: a full editorial staff and a cadre of freelance writers, supported by ad impressions, creating longform music journalism.

Ninety days in, however, it was clear that the financial reality facing NoDepression.com was grim. Fairchild let the staff go, and Blackstock went with them. (Alden had already parted.) She retained me, shifting me from news editor into the role of community manager, and moved the brand onto Ning—a Web platform that was relatively cheap to operate, and allowed us to run ads, though the revenue wasn’t enough to pay journalists.

When I had a spare moment, I edited the community contributions, trying to attract new, talented writers, able to promise them only a captive audience.

For five years, Fairchild and I ran the Ning site by ourselves, working to fix blogging code on the fly—something neither of us was trained to do—and put out fires when they arose. The platform was prone to spam attacks, and I frequently dropped everything to fix them. When I had a spare moment, I edited the community contributions, trying to attract new, talented writers, able to promise them only a captive audience.

That captive audience attracted the attention of Chris Wadsworth, a founder of the FreshGrass Festival—an annual roots music event at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. When he came exploring the idea of buying the publication in 2013, Fairchild was burned out from years of trying to keep the company afloat. She sold to him early the next year and took her exit.

The transition was relatively smooth. I slid into the editor role with a small support staff of copy editor, community manager, and intern. Wadsworth, now the publisher of No Depression, granted me a small editorial budget, believing the best way to continue with integrity was to start paying writers by the word again, then find some way to make the numbers work.

Trending: Brendan Fraser made groping allegation after story was done, GQ staff writer says.

Our monthly traffic rose from 100,000 uniques to more than 250,000. A new ad sales manager ran display ads on the site. By then, however, we had competition: Rolling Stone launched RS Country, film star Ed Helms and his friend Amy Reitnouer launched The Bluegrass Situation, CMT roped in roots music through its website CMT Edge, and other sites started embracing somewhat rootsy acoustic bands like Mumford & Sons and the Lumineers.

The website alone wasn’t enough to bring the company into the black. Since No Depression no longer cornered the online market on this niche genre, there was no choice but to bushwack our way into territory nobody else had dared to enter. So, to mark No Depression’s 20th anniversary, we decided to publish a print edition.

The first issue was crowdfunded via Kickstarter, which raised $78,540 from 2,023 people. Our determination to exclude advertising and pay contributors a fair rate required that we charge $20 per issue, which placed us in the company of cult-following journals like Kinfolk, The Great Discontent, and Fretboard Journal, and we looked to each for ideas.

We decided to leave concert and album reviews out of the book. The nature of the quarterly publication took us outside the release cycle anyway, and short, timely reviews make better sense online.

An exploration of race in country music, a story about how Scottish poet Robert Burns influenced a generation of folk singers—these were the kinds of stories that interested us, but editorial norms would have capped them at 2,000 for the Web. We wanted to give writers room to go as far as possible into a story, and our steadily rising customer base—around 3,200 to date—seemed to be hungry for it.

We learned from our Kickstarter campaign that we had at least 2,000 very loyal readers, so we started our print runs at 2,000 copies. With the goal of retaining most of our readers as ongoing subscribers, we built out a store on Shopify, pushing hard on pre-orders, and modeling our plans after companies like Netflix and Hulu, offering subscribers the option to pay $6 per month, $18 per quarter, or $72 per year. This creates an estimated audience before each “limited edition” issue is printed. A few issues sold out entirely. Thus, more copies will be printed of the next issue—an estimated 3,500 for Spring 2018, with a goal of 5,000 per issue by the end of the 2018 fiscal year.

Helping keep costs down is the skeleton crew that produces each issue over the course of three or four months: an editor, a copy editor, and a page designer.

“The journal is similar to making a handcrafted guitar in your home workshop,” says Wadsworth. “It takes a while and requires a great amount of skill. The materials can be expensive, but it’s a passion project, in service to the music. The result is its own work of art.”

Last year, Wadsworth folded No Depression into his nonprofit FreshGrass Foundation, a 501(c)3 organization he created to support the creators in this realm. In addition to publishing No Depression, presenting the festival, and providing grants to musicians, the Foundation created the No Depression Writing Fellowship. Its first recipient, Sarah Smarsh, wrote 40,000 words about Dolly Parton’s influence on working class women, published in four installments across each issue of the journal in 2017.

Two more fellowships will be rewarded in 2018, and the work they produce during their fellowships will be released in book form. No Depression’s new foray into book publishing will begin this way, but Wadsworth hopes to eventually publish a wider array of titles under the ND Books banner.

As the No Depression quarterly journal enters its third year back in print, managing editor Hilary Saunders plans to overhaul NoDepression.com this spring, making it more reflective of the print journal with a more robust store and a place to spotlight upcoming stories, even as she expands the journal’s coverage of marginalized artists. With the Spring 2018/“Appalachia” issue zipped, Saunders says the Summer 2018 issue will celebrate the music of immigrants and songs about migration. The fall 2018 issue will be dedicated to the intersection of technology and traditional music—something which, given its track record, No Depression knows a thing or two about.

Kim Ruehl is a music journalist and author of the book A Singing Army: The Life and Times of Zilphia Horton, forthcoming from University of Texas Press. She was an editor of No Depression from 2008-2017, ending her tenure there as editor in chief. Her work has also appeared in Billboard, Yes magazine, The Bluegrass Situation, NPR, and elsewhere.