Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

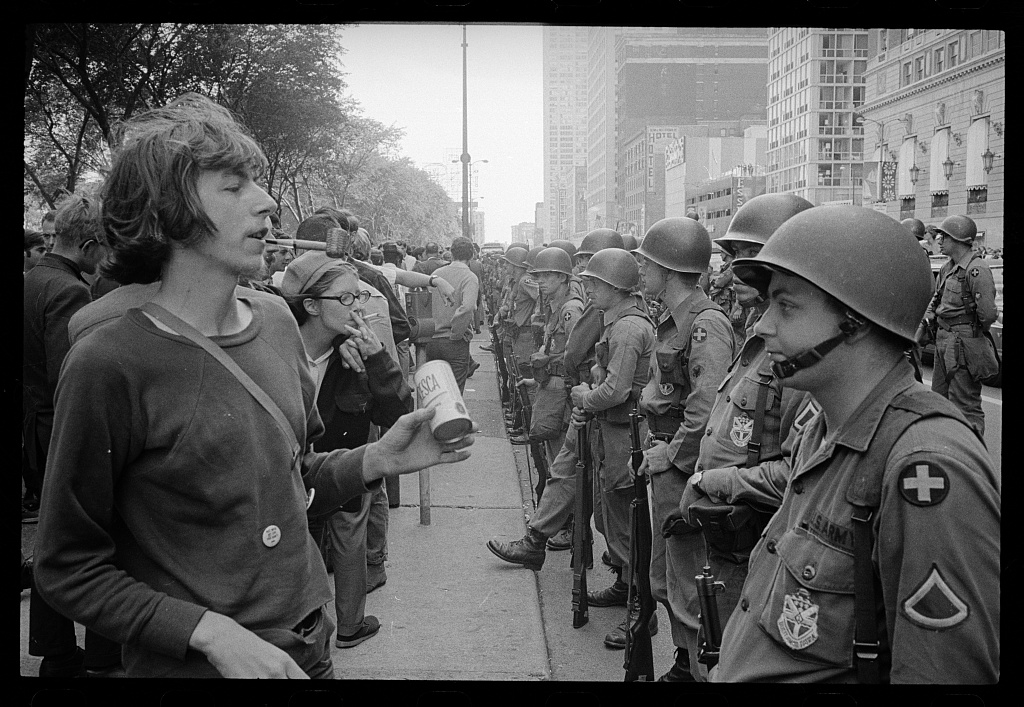

Fifty years ago, in the waning days of August 1968, thousands of protesters descended on Chicago, where delegates were assembling for the Democratic National Convention. Some of the arriving activists hoped to steer the Democratic Party toward a firm anti-war policy; others to mock the two-party system itself and advocate for revolutionary social change. As police pushed protestors out of Lincoln Park, on Chicago’s North Side, chants of “The whole world is watching” made their way into the convention halls and onto the televisions of millions of Americans. Against the backdrop of Lyndon B. Johnson’s concluding presidency—he’d announced he wouldn’t seek reelection—and increasing disaffection with the Vietnam War, the protests brought to a boil a long-simmering acrimony between the growing counterculture and the political establishment.

The ’68 Democratic National Convention and its aftermath also had lasting impacts on journalism. As reporters found themselves bloodied and beaten while attempting to document the unrest, challenging questions emerged about the nature of objectivity and reporters’ relationships both to their bosses and to the public at large. How could journalists be unbiased observers of a situation in which they were—whether willing or not—participants? Did the journalists of 1968 deserve the stereotypes made of them as liberal do-gooders using their public positions to shame average people into moral action? Or had they in fact become so firmly embedded in the prevailing two-party order that they were unable to recognize the overflowing dissent roiling the population until it consumed them too?

These questions grew to existential proportions, spurring changes that continue to reverberate. The news media became more suspicious of official declarations, establishing a critical distance that would become particularly consequential in the era of the next president, Richard Nixon. And reporters increasingly turned a focus onto the experiences and actions of regular people.

While these developments have been important to elevate the quality and accuracy of journalism, some of the biggest quandaries facing journalists who covered the 1968 convention remain with us today. Namely: What drives people to hold the press in contempt? And how does a critical news media cover opinions from people outside its cultural milieu—the voices of mythical Middle America—without resorting to patronizing exoticism or bend-over-backward appeasement?

As we contemplate similar questions facing journalism today, CJR takes a look at the impact of the DNC protests of 1968 on the journalism of its time—and ours. Below is an oral history of the convention and its journalistic fallout, assembled from interviews with people who were there, as well as from transcripts from a series of events examining the convention a half century later, hosted by Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.

Participants: Donna Leff is an award-winning investigative journalist and professor at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing, and Communications. David Farber is a history professor at the University of Kansas and the author of Chicago ’68. Hank De Zutter is a former education reporter at the Chicago Daily News and a cofounder of the Chicago Journalism Review. Don Rose is a political consultant who served as the press secretary for the National Mobilization to End the War during the 1968 Democratic Convention. Rick Perlstein is a historian and author of several books on American conservatism, including Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. Robert Scheer is a communications professor at the University of Southern California; in August 1968, he was the editor in chief of Ramparts, a now-defunct magazine prominent during the 1960s.

Donna Leff: [A reporter friend of mine] said that covering the convention was actually the seminal point in his career in journalism. I asked him why, and he said because for the first time he and a lot of his colleagues realized that “officialdom” was feeding you crap, and everything you heard from officials wasn’t true. I know that seems hard to believe now, but in 1968 that was a new thing. Usually people date that back to Watergate, but really you should roll it all the way back to 1968, because that’s really when we first kind of thought that.

David Farber: Who is telling the truth? What is the media supposed to do? In 1968, you start to see those two big paradigms. . . start to become issues that the news media have to constantly think about. Now most newspapers, most producers, most editors are still operating in a very narrow political parameter, but the questions are now there, and political authorities are aware that the media is no longer simply mouthing established lines—mostly it is, but not completely anymore.

Hank De Zutter: Before the convention started, this was not considered that big a story. I was the only reporter at the Daily News [who], when asked what part of the convention I wanted to cover. . . said I wanted to be on the streets. Everyone else wanted to be with this delegation, that delegation. We were kind of conditioned to think that politics happened at meetings, and politics happened in the suites—not on the streets.

Because I was an education reporter, covering a lot of campus dissent, I began to see a national movement emerging, and I wanted to be there for that. I heard Bob Dylan go after reporters, saying, “Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?” Well, I didn’t want to be Mr. Jones; I wanted to be out there covering this in a serious way.

DF: By 1968, if you were a professional journalist, you had already faced some real sea changes in your business. The racial-justice movement had already been around for a long time. In 1963, another seminal period, journalists had to rethink who is newsworthy: Is it simply the president and authorities that have high-ranking positions? Or is it young civil rights activists, the people in the streets? Are they newsworthy? How so?. . . The social-change movements understand they have to grab the attention of the American people and the networks. Big-time journalists have to decide: Is it headline news? Back pages? Or is it in the news hole at all?

Don Rose: One of the interesting things for white reporters (which is almost redundant at the time), was that there wasn’t really such a thing as police brutality. In the newsrooms of the day, police brutality was the complaint of “those people out there,” and whenever it was brought up, it was, “Oh, check with the mayor, is there police brutality? No.” That’s something that only happened to “those people,” if it really happened. Finally we saw a bunch of white people getting beat up, and slowly it seeped in that there was such a thing as police brutality. It was some years before they started really writing about it, but that was a sea change.

Rick Perlstein: Lew Koch was an NBC News producer in 1968, with a specialty in stories about the civil rights movement and anti-war movement. He was also a sympathizer for those movements, and he was given the task of producing the street footage at the convention. He was inordinately proud of what he was able to produce in the streets of Chicago. What he thought he had produced was the 1968 version of what people in his job had done in 1963 in Birmingham, in 1965 in Selma: produced a crystalline theater of moral witness—evil being visited upon innocents.

He went back to NBC’s [Chicago] headquarters at the Merchandise Mart, and things were pretty busy. His boss asked him to help man the switchboard, and…he began receiving calls, and what he was hearing from people calling in, making the effort to call in, was absolutely shocking to him. They did see this as a theater of good versus evil, only the terms were precisely reversed [from] what he thought he was presenting: The cops were the innocents, the protesters were the aggressors. And not only that, but the real villains in the story were the news cameramen, who in some cases were accused of staging the violence in order to make for a good show.

HD: I must confess. . . I didn’t know how the hell to cover the stuff that came down that Sunday in Lincoln Park. It was crazy. My own reportage, the reportage coming in the newspapers, was pretty bad. It was difficult to figure out what was going on. The cops came into the park, pushed everyone into the streets, and all of a sudden we have 150 different police actions on different corners. One person would see this, another person would see that. How are we reporting this?

How would I write it now? “Scores of Chicago police freely using clubs and spraying tear gas drove hundreds of anti-war and anti-convention youth out of Lincoln Park and into nearby streets Sunday. . .” That’s what happened! “One hundred and twenty-five were arrested, hundreds injured, including 20 police and 21 news reporters and cameramen, who were covering the action.”

I must confess. . . I didn’t know how the hell to cover the stuff that came down that Sunday in Lincoln Park. It was crazy.

But we didn’t write it that way. We were afraid to say it. Here’s the way we wrote it, here’s the Sun-Times: “Hippies and the police clash. Thousands of shouting, chanting hippie-clad youths. . . clashed with police on Sunday night in a series of incidents [that] began in Lincoln Park, spilled over to Michigan Avenue, and halted traffic for blocks in Old Town area.”

We could not report what we were later talking about in the bars, like, “Boy, those cops were like straight out of hell!” We couldn’t give any of that kind of flavor or spirit to the writing. As reporters on the streets, we were these strange characters that floated above it all. There was one important difference, and it was a harbinger of things to come: The Sun-Times reported that one of their own photographers was attacked and hurt by police who had removed their name tags and badges.

DF: By 1968, there is a war between the political establishment and broadcast journalists, and to a lesser extent [newspaper] reporters, about what something like a convention is supposed to be. How do you cover this event at this time in American history? There’s a negotiation. In 1964, there are 54 floor passes for journalists. In 1968, there are seven floor passes—[and that was] on purpose, to try and narrow who was controlling the agenda. So you’ve got an organized effort by Mayor [Richard J.] Daley and other Democratic Party officials to reduce the parameters of what Americans will hopefully see about the convention. You’ve got everything from Yippies to [Students for a Democratic Society] to the National Mobilization Against the War trying to get their perspective somehow across to the American people.

Robert Scheer: A lot of people, both in the hall and outside, trusted us [at Ramparts]. By then, they were very distrustful of the establishment, whether it was the political establishment or the media. They felt that protests in general were distorted in the coverage, both by established authority and the conventional leadership of both parties. There wouldn’t have been a Ramparts if The New York Times had been doing its job.

[Mainstream journalists had] a cozy relationship with the people putting on the convention. You want their confidence and trust, and there’s this rabble outside, and you’re less inclined to care about what they’re saying. It’s not convenient to your working conditions. You’ve already got your cameras set up in the hall, you’ve got your interviews spaced, you’ve got your deadlines scheduled, you’ve got your exclusives. That’s not conducive to an open mind. In the main, your working journalists, basically, want to advance their careers, they want please their bosses.When the story shifts out to the street, you see it as theater. Let me get Abbie Hoffman, let me get Jerry Rubin, the crazier the better, and then I’ll make that the story. The pressures of the job, even at [the] best of times, were horrendous.

RP: The media was a lot more confident in itself, and that confidence was what allowed Spiro Agnew to speak so eloquently and effectively. He literally talked about them like they were an unelected aristocracy, and they could come off that way. If you watch old newscasts from the sixties, there were these old white men who just kind of had the voice of God. Walter Cronkite going on TV and confidently saying that the Vietnam War is going wrong, we have to make a peace deal. These guys were princelings, certainly the network news anchors, certainly the big columnists. They were intimates to the president.

They were not used to being criticized, or they were not used to the criticism mattering. National Review might criticize them. People who didn’t matter might criticize them. But presidents wouldn’t criticize them. It’s just such a big thing about Nixon: He turned the press into an enemy, and the Chicago convention was a very big part of how he was able to do it.

HD: The mayor and the police spokesman defended the police action, blamed the reporters for being attacked, for being there, for making these stories happen, for exaggerating what the police were doing, and even staging riot scenes, so we could have more interesting coverage. This official criticism of the media intensified as the national media pulled out, and so here we were, local reporters, being submitted to an almost daily revisionist version of what really happened on the streets, telling us what we saw didn’t really happen. We even printed at the Daily News Mayor Daley’s own report on what happened, in which he criticized the media. We didn’t contend with it. We just let it run as it was, you know. We were really frustrated, those of us who had been there, so what do you do when you’re frustrated and your needs aren’t being met? As Alexis de Tocqueville said, first you form an organization. So we founded the Association of Working Press, and we put out the Chicago Journalism Review.

DF: For the media, this was a moment of truth, and I think out of this moment comes a more conscious understanding that the news can be more than simple reportage of elite figures. You start to see for the first time a greater hold in newspapers for analytic pieces, a new kind of genre in the newspaper business. Opinion pieces are more widely used. Is this a popular move? Does this change the way people regard journalism, in newspapers especially? We’re still living with that legacy.

RELATED: (MORE) guided journalists during the 1970s media crisis of confidence

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.