Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The word “disagree” (不同意 in Mandarin) disappeared from Sina Weibo, China’s Twitter equivalent, in late February. The change came shortly after China’s Communist Party (CCP) announced its proposal to amend the constitution, which would allow President Xi Jinping to hold his position for longer than two terms. On March 11, the proposal was approved at National People’s Congress with 2,958 votes in favor, two opposed, and three abstaining. But since the measure was first announced, when trying to post any tweet containing the word “disagree,” Weibo users received a system error message saying the message was “illegal.”

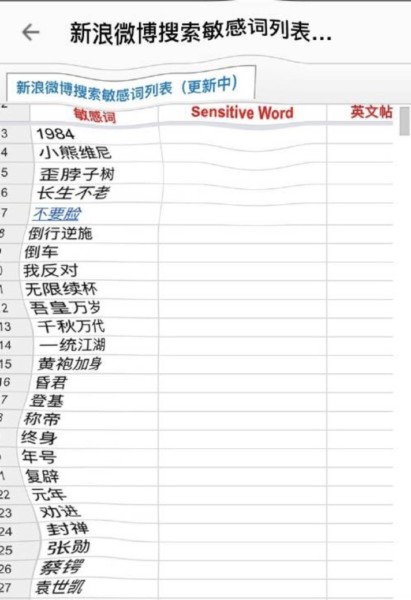

The disappearance of “disagree” is the tip of the proverbial iceberg—this was a silent race between social media users and an unseen authority. Following Sunday’s announcement, a new wave of online censorship hit the country, banning a slew of similar phrases. Much like all the previous peak seasons of online censorship, there was little warning and no explicit list of “sensitive words” (敏感词, slang for banned keywords). Instead, users gradually pick up on which words are blocked, with tweets deleted and accounts suspended.

Trending: The queen of spin: How the president’s daughter plays the press

But this time, the censorship went far beyond the usual methods.

At 5:33pm on February 25, China’s Xinhua News Agency broke the news of the constitutional amendment on Weibo. The amendment would abolish the two-term limit for the presidency, set in 1982 under Deng Xiaoping’s rule—a historic move that was seen by many as a landmark of China’s reform from Mao’s dictatorship. According to Xinhua News Agency, the proposal had “extensive support” from both politicians and the general public.

However, the reaction on social media was heavily censored. The announcement on Weibo initially collected more than 97,000 retweets and 3,300 comments, none of which are now visible. Posts about the amendment—supportive of the change or otherwise—were removed indiscriminately. A number of words were censored, including common keywords like “oppose” (反对), “ascend to throne” (登基), “immigration” (移民), and “restoration” (复辟). Others were more allusive, like “backing a car” (倒车), “animal farm” (动物庄园), and “1984.”

Even common countercultural codes, designed to get around censors, failed. The phrase “500 years” was nixed, which alludes to the lyrics of a pop song about Chinese Emperor Kangxi, who wanted to continue his reign for five centuries. Similarly, “Yuan Shikai,” the name of the Chinese politician who attempted to briefly restore monarchy in 1915, was temporarily banned from Weibo.

“A lot of these (keyword censorships) are short-term measures. Their main concern is to stop the public attention,” says Dr. King-wa Fu, the scholar who founded WeiboScope, the Weibo-monitoring project at University of Hong Kong. Since 2014, Fu’s team followed more than 120,000 Weibo users daily, crawling their public posts. In 2017 alone, they documented 20,651 deleted posts.

As Fu predicted, most keyword bans were lifted days after the passage of the amendment (with the exception of “disagree,” which is still considered “illegal” in Weibo’s comment section as of this writing). For many of those suspended phrases, Weibo’s search function has also been restored, though the results appear to be filtered.

When text is censored on Weibo, industrious users usually turn to screenshots and memes. For instance, after a tweet by Dr. Yinhe Li, a renowned Chinese sociologist, was deleted because it called the constitutional amendment “backwards,” a screenshot of the post instantly went viral. Similarly, a meme created from the Chinese TV drama Empress in Palace spread. In it, one character says, “I pray the emperor to drop dead, and I’ll be vegetarian for life.”

Because Chinese censorship usually favors text, screenshots and photos generally last longer on social media—but not this time. Weibo now seems to be using photo detection technology to delete sensitive screenshots and memes. The Empress in Palace meme, for example, can no longer be uploaded to Weibo. To fight this photo-detection technology, some users attempted to warp the photos before uploading them:

Users also attempt to avoid censorship by retweeting old Weibo posts that could be understood to hint at the current affair. After all, these messages had been previously approved by the censor. For instance, a three-year-old post from Xinhua News Agency was picked up by Weibo users and forwarded more than 4,000 times before Weibo intervened. Taken from Xinhua News’s “Today’s Historical Event” series, it discussed Yuan Shikai’s failed attempt to restore monarchy in 1915.

Similar things happened to Disney’s official Weibo account. Memes based on Winnie the Pooh, the cartoon character often said to resemble Xi Jinping, are widely used to poke fun at the president—to such an extent that the character was briefly censored in 2017. As news broke and censorship became rampant, Weibo users suddenly discovered Disney China’s account was a rich supply of political satire. A post from 2013 that went viral features Winnie the Pooh hugging a jar of honey, and it became a funny reference about how Xi would not let go his power. “Find the thing you love and stick with it,” reads the caption:

But the authorities cracked down on these posts as well. The historical Yuan Shikai story on Xinhua News survived—but comments and reposts did not. People can no longer leave comments on Disney China’s post.

Weibo, as a platform, has become much less permissive in recent months, since the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) imposed a severe fine on the social media organization in September 2017 for failing to censor improper content. According to Reuters, Weibo later hired more than 1,000 citizen censors, who are paid to flag 200 posts an hour in the monitoring system—which means these subtler cultural references are caught more often. Sarcasm, metaphor, and similes were all subject to censorship after last week’s news.

“(My post) is difficult to detect with language analysis, but once it went through manual censorship… It had already been reposted for over 6,000 times—there’s no reason not to delete the tweet,” says Weibo user @ZhuDingZhen (竹顶针), 28. One of his tweets became viral and then went missing within hours. The tweet reads,“Haha it was hard to understand when I was a kid: Why does everyone get ‘you-know-who’ is Lord Voldemort. And later I realize JK Rowling is wise indeed.”

“Once (your tweet) enters the public domain, and people start circulating and retweeting, it might reach the Big V (“verified influencer” in Weibo slang, denoted by a golden “V” symbol next to the username) and the voice will be amplified. Then it will attract censorship or even punishment,” says Dr. Fu.

Related: How WeChat became the primary news source in China

Punishments may be severe. Soon after Xinhua News’s announcement, many users realized they could no longer log into their accounts—they were either temporarily suspended or permanently deleted. The latter is called “Zha Hao” (炸号), and means “account bombed” in Weibo slang. The extent of the suspensions seemed unprecedented.

Even supporters of the amendment saw their accounts targeted. @DaiJiaFaDeNanGuast (戴假发的南瓜st), for instance, did not object to the idea of changing the constitution, but his account was “bombed” anyway. In the post that provoked the account’s demise, he expressed that Xi made a brave move to “choose a hard way and sacrifice himself for the country.”

According to Lotus Ruan, a researcher at The Citizen Lab, an internet-watching laboratory based in Toronto, “In many cases users are no longer notified when their messages are censored.” Some don’t know why their accounts are suspended.

Censorship wasn’t limited to Weibo. Zhihu, the Chinese equivalent of Quora, was banned from the Android app store for a week due to its unsuccessful handling of “illegal information,” although the site has been diligently deleting users’ loaded questions (e.g., “What would you do if your driver insisted on driving with fatigue and refused to take shifts?”). Douban, the Chinese social media for movie and book reviews, quietly coined a “media score” for propaganda movies to avoid the users’ low ratings for those works.

As most of Chinese social media is under extreme scrutiny, decentralized technologies like blockchain have started to raise hope among some Netizens. After the recent round of censorship, a number of influential users who were kicked off of Weibo turned to Matters, a blockchain-based Chinese forum still under beta testing. Eventually, Matters plans to give Chinese citizens a way to speak out that cannot be erased by censors.

“It’s much easier to get users over the past week, now that you tell them that discussions on [our] blockchain-based forum will be kept permanently,” says Annie Zhang, Matters co-founder and a former New York Times columnist. Zhang was having difficulty persuading industry experts and academics to join the forum and stay active, but that’s changed. “These days, social media is a lifeline to people,” Zhang says, “and many of them are being scooped out.”

After the amendment was proposed, philosopher Dr. Po Chung Chow joined the forum and shared his thoughts about the recent censorship. Written with all the “sensitive” words, the content could hardly be published on Weibo, where he has nearly 200,000 followers. Murong Xuecun, a writer who’s a household name in China, also joined Matters last week. He had almost four million Weibo followers until his account was shut down permanently in 2013.

To welcome new users, Zhang hosted an online sharing session on March 6 so newcomers could talk about the experience of being expelled from different platforms. The online keynote speaker was Xue Jiang, an independent journalist who was “bombed” multiple times on Weibo and had her personal account banned from WeChat last week.

“I am just like countless other people; struggling, hesitating,” Jiang wrote. “On Chinese internet, we are the information refugees.”

ICYMI: A source emailed me his life’s work. Then, he ended his life.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.