Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Li Zixin was bummed out. It was 2011, he was in his early thirties, and he was working a PR job for a company that he described as high-paying but “nihilistic.” Two years earlier, he’d left a career in journalism—he’d been a deputy editor at Global Observer, the magazine affiliated with The Oriental Morning Post, in Shanghai, and a tech reporter for the 21st Century Business Herald. But now newspaper readership in China was declining, and opportunities (as well as salaries) were not what they once were. People had begun spending more time on their phones—in big cities, smartphones have all but completely replaced menus, transit cards, and cash—instead of reading print. The digital reckoning, which came to China a few years later than it did to the United States, was a blow to journalists, who already had plenty to contend with: China’s Central Publicity Department—known in Chinese as the Central Propaganda Department—controls virtually all of the country’s newsrooms, magazines, television programs, and films. The print outlets that exist today are almost entirely state run.

Still, Li had felt a sense of purpose in reporting, and he was beginning to miss it. He was also beginning to take an interest in Weibo (China’s Twitter), where he followed fellow members of the sandwich generation—thirty-somethings, many of them single children working jobs they didn’t like in order to meet the burdens of their multi-generational families. On Weibo, people chronicled their resistance to social pressure—how they abandoned corporate careers and pursued art or music or entrepreneurial ventures. This phenomenon, Li found, was completely absent from the journalism to which he was exposed. “Mainstream media isn’t so sensitive to subtle social change,” he says. Weibo could give voice to the sandwich generation, but writing on the platform was too fragmented, unfocused, amateurish. “Weibo was good at breaking news, at using a very short message to disclose what was happening,” Li says. “But there were no long pieces. No depth.”

So he began writing. While holding onto his gig in PR, Li began interviewing anyone he was intrigued by on Weibo and asking friends to send interesting characters his way. He built a website himself, naming it China30s in honor of the sandwich decade, and began posting stories—on a Bulgarian man in Shanghai, on a long-distance runner, on a practicing Christian.

Six months later, Li quit his PR job and made China30s his priority: It would be a general interest online magazine, with profiles and trend pieces. He knew that he needed funding, but he turned down a pair of venture capitalists who offered to buy a 20 percent stake in the company—even 20 percent, Li says, would lead him down a slippery slope; he never wanted to answer to profit-driven shareholders. Traditional online advertisements, he thought, would inevitably lead to low-quality clickbait. With few options, Li resolved to try something different: If readers liked what they read on China30s, they could pay for a class in which Li taught them how to produce their own stories.

The first courses, which had about a dozen students, took place in Shanghai, where Li borrowed extra office space from a friend’s start-up, and Beijing, where he rented the first floor of a small house. Later, he opened an office and a classroom in the XuHui area of Shanghai, and began teaching lessons online. Mo Zhou, an English teacher from Shenzhen, signed up. “It was the first time I realized people were actually interested in my writing,” she recalls. In a piece about her marriage to a man from Slovakia, she delved into cultural differences and generational conflicts. “I wanted to convey how I struggled to strike a balance between the expectation of my parents—who, as most parents of their generation in rural China, saw children, especially daughters, as their properties—and my pursuit of becoming an independent individual, both financially and psychologically.” Mo, who went on to write a series of pieces about cross-cultural relationships, became one of many converts from site reader to contributor. Today, between 10 and 15 stories appear on China30s each week, and many come out of the writing classes. It isn’t professional content, nor is it user-generated content, Li says, it’s “trainee-generated content.”

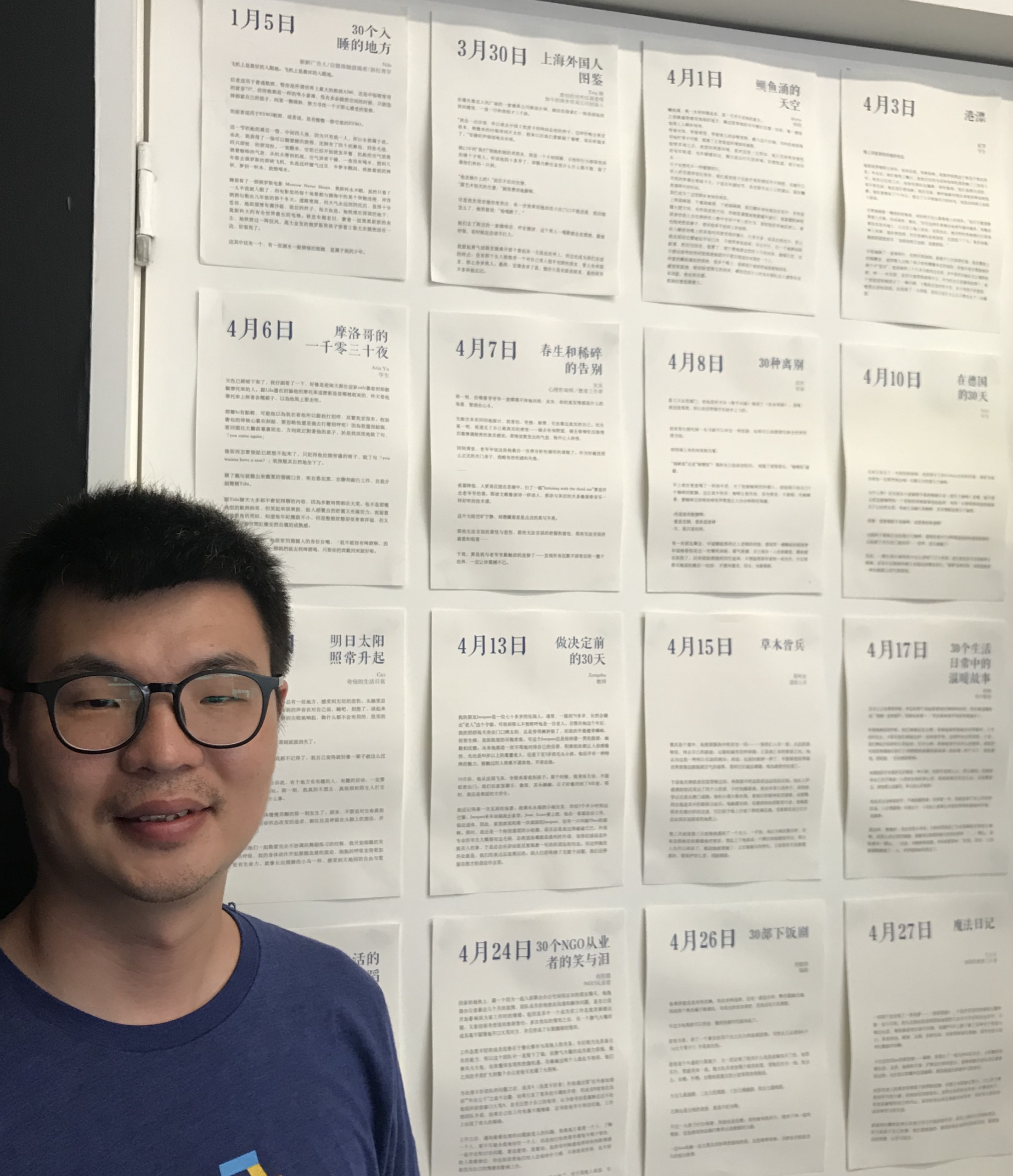

The other day, at the China30s office, Li, now 39, looked laid back in a navy blue T-shirt and joggers. The site now has 11 people on its staff, he explained, and many other frequent contributors, including Mo. Li showed me a profile of Zhou Siling, a Chinese-American man living in Shanghai, who had gained fame with a viral video, “LBH—Loser Back Home,” that parodied westerners coming to China expecting to be treated like hotshots; the piece described how Zhou felt “pressed between east and west.” A recent story, “Why Having a Baby Is a Nightmare for China’s Post-90s Couples,” told of a woman with post-partum depression burdened by an expectation that she share getting-back-in-shape selfies.

Translated books by Gay Talese and Bill Moyers were scattered around, as were copies of The Paris Review. From a bookshelf, Li pulled a copy of Hillary Clinton’s What Happened, which he had picked up on a recent trip to the United States. “The defeated party’s leader publishing a book,” he says, is unfamiliar to those in places where “the defeated party is silent.” For China30s, covering politics is completely off the table. Dissent in his country now comes almost exclusively from private messaging platforms, like WeChat, where an individual account may be able to get away with political criticism (though not without serious obstacles) that a newsroom couldn’t. Li, who values story above scoops, is less interested in pushing boundaries than he is in publishing compelling pieces within the boundaries prescribed. “It’s not perfect,” he says. “But if you’re a writer in China facing censorship, what could you do? Life goes on. There’s still room to do really nice stories, ordinary people’s stories.”

In his writing courses, Li aims to train students in the ways of polished prose and multiple sources. “In my years as a journalist I was trained in these writing skills,” he says. “Now I try to carry on the spirit—at least some of the spirit.” The students are of all ages and backgrounds, and often write based on their experiences—a state employee chronicled the woes of working for provincial government; a woman employed by border security in Hunan described stopping a tiger bone smuggler. At $200 for a five-week workshop, the tuition is a kind of down payment for someone who wants to contribute to China30s—or, in some cases, tackle more controversial topics on a monetized WeChat account, where success may depend, at least in part, on writing quality. Is this an exploitation model? By way of reply, Li points out that students who publish more than three pieces on China30s are paid. Besides, he says, it’s better than content made by algorithms.

China30s, which gets about 10,000 page views a day, largely eschews the prevailing media trends: recommendation algorithms, ad-driven revenue models, sponsored content. Most of China’s popular news websites and apps are owned by massive corporations, such as Tencent and NetEase; Li has remained, after 6 years, firmly independent. One app, Toutiao (“Today’s Headlines”), goes as far as to identify not as a media company but as a tech company. Launched in 2012, Toutiao, which boasts 150 million users, aggregates articles from across the internet in a manner similar to Apple News, and allows anyone who creates an account to post their own stories; revenue comes from ads. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a Beijing-based think tank, warned recently in a report about the “mimicry environment” and “information cocoons” created by this model; Pu Xiao, a graduate student at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences who researches Chinese media, tells me, “If I want to see something new, it’s hard for me because I have to delete the app and download it again.”

It’s a tough market in which to pursue original storytelling—even Caxin, a prominent financial magazine, moved last October to be the first news company in China to put up a paywall. Over the years, Li has dabbled in video—commissioning a series on young creatives—and the influencer beat—penned off in its own section. But he abandoned those experiments. Recently, to increase the company’s revenue, he has embarked on a few new projects: “Daily Book,” an online space for students to share drafts with peers and professional editors; writing courses for children; classes at the Shanghai library. In May, China30s organized a storytelling festival in conjunction with the Wuyuan Lu neighborhood; a follow-up planned for this fall. There is also an English-language version of the site, with some rough translations, which he hopes to refine over time.

Over lunch, Li said that growth isn’t his ultimate goal. “I’m really not in favor of this being taken to a big scale,” he says. “The meaning I pursue in China30s is in doing something new, an experiment, something that will reflect the current Chinese era.” Lately, he’s been worried about can be seen in China’s reflection. Picking up his phone, he opened up Douyin, a popular entertainment app, and turned the screen to me. A short video played, of a young woman counting how long she could hold an orange slice between her upper lip and her nose. That lasted about ten seconds. Then another video began. He sighed. “Check the front page of these apps,” Li says. “Always what’s most sensational is at the top. It makes it all very low. Low—the English word—is very much a buzzword here right now.”

ICYMI: Journalism as Jihad in Afghanistan

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.