If there’s one—and only one—thing we can say definitively about fake news, it’s that it inspired some great reporting, of a kind that has never before been prominent in the public sphere. Exhibit A is Craig Silverman’s coverage at BuzzFeed, which brought a level of rigor to the speculation around the spread of disinformation after the election.

For those journalists without a computational background, many of his reporting tools may seem opaque. How does a journalist go about tracking how fake news stories have circulated on social media, much less assess their partisanship en masse?

Thankfully, for the rest of us, Public Data Lab and First Draft News have produced a “Field Guide to Fake News,” launched today at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy. (Not to be confused with “Tips for Spotting False News” released by Facebook yesterday.) First Draft News, headed up by Claire Wardle (formerly research director of the Tow Center), has become the go-to resource for understanding how to source and verify material discovered on social media.

While the Guide is not explicitly geared toward teachers, it is chock full of exercises to guide us laymen through the legwork of understanding how stories travel on social media. The exercises are called “recipes.” The “ingredients” are a set of links to fake news stories you want to track. Recipes come in different “flavors” depending on how tech savvy the reader is. And the serving suggestions include how the recipes may be used to encourage better understanding.

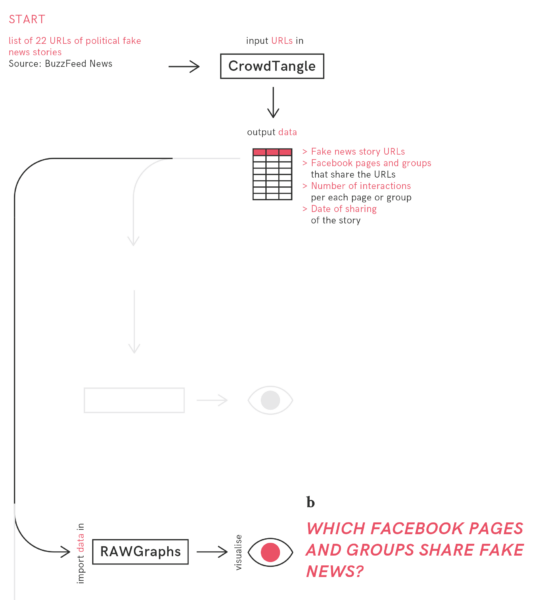

The beautifully produced graphics look like workflows to aid the reader step by step. Take the first recipe, for instance. The authors suggest using a BuzzFeed list of top fake-news stories, but any set of links will work. The reader is instructed to put the URLs into a free browser extension from CrowdTangle, which spits out what Facebook groups and pages have shared those URLs the most.

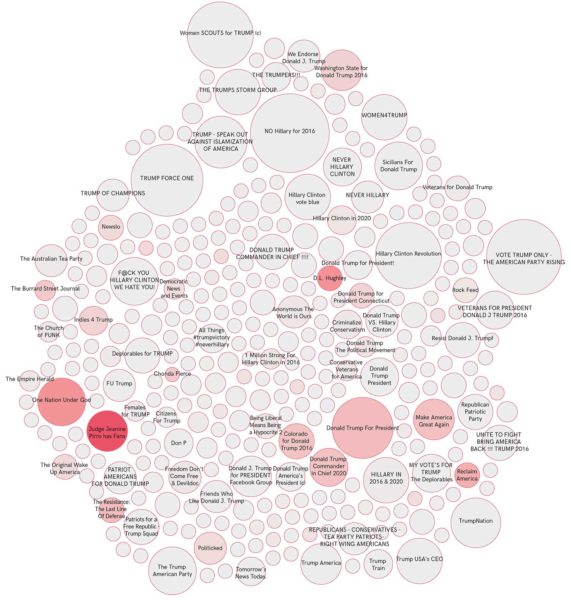

You end up with a manageable list of Facebook groups, which can be visualized as a network (the Guide suggests the tool RAWGraphs) showing how many followers each page has and the number of items each shares.

The third recipe looks at how a journalist might go about assessing how effective counter-initiatives are against fake news. How did the links debunking fake news perform, as opposed to the fake news itself?

The circulation of these stories is so important because fake news doesn’t matter much if it’s not viral. As the Guide notes, “False and misleading knowledge claims are not born ‘fake news.’ To become fake news they need to mobilize a large number of publics—including witnesses, allies, likes and shares, as well as opponents to contest, flag and debunk them.”

Unfortunately, from the user perspective, distribution of content on social media is so fragmented that it can be difficult to put together a cohesive story. The reader who goes through these exercises with patience will not only discover stories, and grow in understanding of how news travels these days, but also gain a crucial set of skills for understanding media consumption in the new era. Plus, it offers a set of free tools—browser extensions and graphics tools. (Stay tuned for more recipes from First Draft in the coming months on memes, bots, trolls, propaganda, and fact-checking.)

“While there may be a sense of fatigue around the issue, it is not going to go away,” co-author Liliana Bounegru writes in an email. The point of the guide aims to provide “inspiration . . . for collective inquiry” into how fake news spreads.

This article has been corrected to list Public Data Lab as the principal producer of this Guide.

Nausicaa Renner is digital editor of CJR.