Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

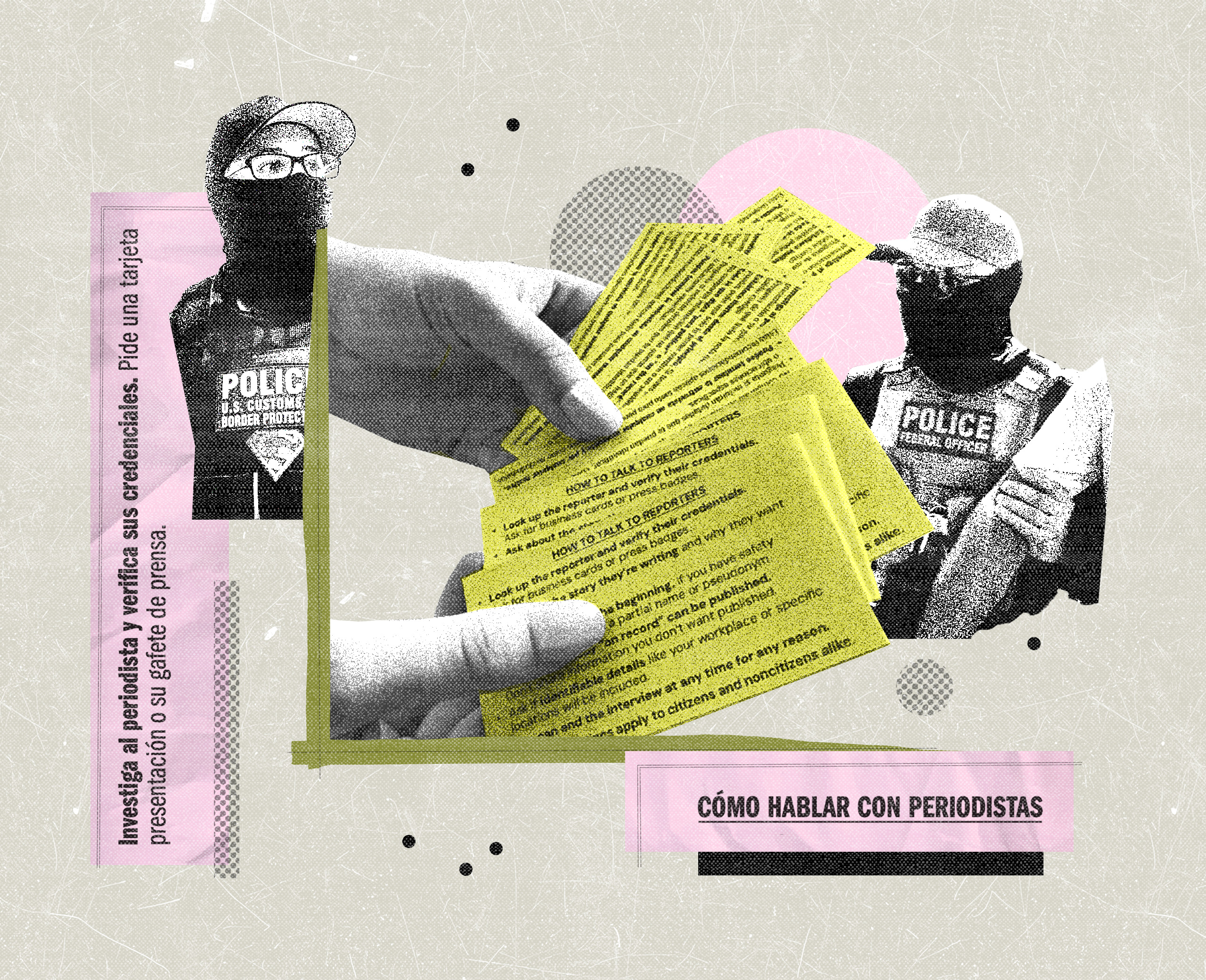

Red is for ICE. Green is for journalists. Those are the colors of the bilingual information cards that LA Public Press, a nonprofit newsroom, started distributing to Angelenos this year as a quick reference guide on how to navigate ICE encounters and how to handle interactions with the media. The ICE cards came first, in June, when the National Guard was deployed to Los Angeles. The media cards were issued after protests in the city became the focus of national coverage, and reporters sought to speak with residents who were vulnerable to ICE raids.

Michelle Zenarosa, LA Public Press’s editor in chief, saw that people needed guidance on their rights not only when dealing with ICE, but also in talking to the media. In July, the LA Times published a story about immigration raids in which some of the subjects were identified by their full names and professions. According to Zenarosa, some people interviewed for that story told LA Public Press reporters they hadn’t understood that everything they told the LA Times reporter could be used in print. The inclusion of their names and job titles in the article upset them, she said.

Gustavo Arellano, the LA Times reporter for the story in question, said that he did not receive any complaints after publication. He identified himself as a reporter for the LA Times and asked people if it was okay to quote them using their full names. He also said that he honors requests from sources who want to be identified by their first names only. “You always have to be sensitive of who you’re interviewing,” he said.

Martín Macías Jr., a reporter for LA Public Press, has seen unintended consequences play out for sources in articles he’s published. In August, two bus drivers Macías interviewed for a story were fired for speaking with him without permission from the transit agency. The following month they were reinstated, thanks to public pressure. The drivers are now fighting for back pay.

To help avoid misunderstandings between reporters and their sources, LA Public Press started handing out cards going over what on and off the record mean, advising people responding to interview questions to “watch for leading questions that push a narrative you don’t agree with,” and asserting that “you have the right to decline uncomfortable questions.”

In March, several news outlets told CJR they were distributing media fact sheets and loosening rules around anonymity, particularly as pertaining to subjects who may be undocumented. Since then, reporters for LA Public Press, Borderless, and Chicago Block Club who cover immigration raids and protests in their cities say that the risks to undocumented people have only increased. All of these newsrooms are taking precautions to protect vulnerable sources, including being more open to granting anonymity and communicating clearly with people what it means to be talking to a reporter and how their words might appear in print or online.

“I think it’s incumbent on the journalists to do their due diligence, to explain what it means to have your likeness, your full name, online or in print, especially given how aggressive this administration has been to immigrants,” said Mauricio Peña, the chief of staff at Borderless, a Chicago-based outlet.

Heightened risk to individuals means that reporting on those individuals requires extra caution. Lately, LA Public Press has become more liberal in making sources for its stories anonymous, or giving only their first name. In some cases, even when an undocumented source consented to being named, the outlet withheld it or other identifying details. Macías said that undocumented sources and activists alike are afraid. “When I covered the George Floyd protests here, that’s not something that I encountered,” he said.

Bruce Shapiro, the director of the Global Center for Journalism and Trauma, has been conducting trainings for local nonprofit newsrooms in Chicago. He said that longtime policies around source protection have enabled journalists to cover sexual assault cases without naming survivors and mandated that outlets seek parental permission when interviewing children. While the balance between transparency and protecting sources has always been tricky, Shapiro said that newsrooms might be in a position now where they need to consider offering similar blanket protections to undocumented immigrants.

“Now we’re in an entirely different era in which there are active roundups of migrants, often undocumented, sometimes documented, in which people’s visibility has made them a target,” he said. “Vulnerability is far from an abstraction. It’s about the real, imminent threat of arrest.”

Figuring out how to report on people living in fear of ICE has urgent stakes. “It’s actually become a press freedom issue,” Shapiro said, “because to the extent that people are afraid to talk to journalists or journalists are afraid to ask questions, our ability to report is being hampered by the arbitrary widespread crackdown and violence.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.