Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In 2010, ESPN’s Henry Abbott issued a challenge to basketball journalists to write a game summary focused on defense, “just to see if it’s possible.” Some writers took him up on it and produced detailed analyses of defense in an array of playoff games. Reading their stories feels like inhabiting an alternate universe, one in which we only see the player with the ball in our peripheral vision, because the defender is in the spotlight, instead of the other way around. The gimmick never caught on.

But the media’s convention of treating major sports moments as successes or failures of offense may be starting to change. The wave of advanced statistics sweeping American sports is finally delivering measurements of defense, which have always been few and far between compared with the numbers that have traditionally represented offensive prowess, like home run and touchdown totals.

The new defensive data could certainly help journalists illustrate why certain teams and defenders are good at stopping opponents. But it is unclear how much it will enhance most fans’ interest in that half of the game. Many writers and analysts do not believe that deeper understanding will necessarily translate into media attention.

“It’s just ingrained in the American sports fan’s psyche to cheer for scoring more than anything else,” said Howard Beck, an NBA writer at Bleacher Report.

You’re measuring things that don’t happen. … A lot of how we understand defense is through how it changes offense.

One reason for this may be that, whereas offensive players initiate the action, defense is reactive in nature. This not only makes it less exciting, it makes it harder to measure, according to Andrew Miller, a PhD candidate in computer science at Harvard. Miller teamed up with three colleagues there to compose one of the winning papers at last month’s MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, the most heavily covered event in sports analytics. (Both victorious papers were about defense; Miller and company wrote about basketball and the other winners wrote about baseball.)

“You’re measuring things that don’t happen,” Miller said, in that the impact of a good defender shows up mainly in the lowering of offensive players’ rates, like their shooting percentages. “A lot of how we understand defense is through how it changes offense. So you kind of need to have a good understanding of offensive skill to get a good understanding of defensive skill in the first place.”

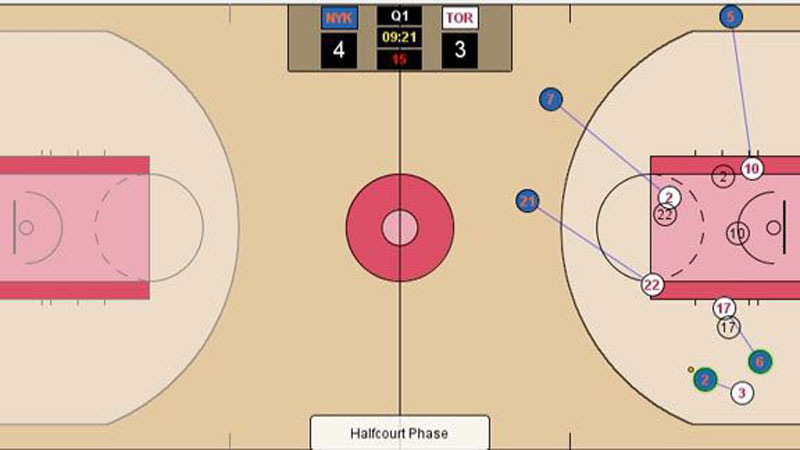

Nonetheless, Miller’s group used new player-tracking technology installed in NBA arenas to develop more precise measurements of which defenders were responsible for allowing how many points, and against which opponents. Journalists can use that data to convey facts about players that had previously been unknown or merely subjective. For instance, the numbers add substance to the general impression that Los Angeles Clippers’ point guard Chris Paul is a solid defender: Players rarely attempt shots against him and, when they do, they score with decreased efficiency.

SportVU, a system installed in all NBA arenas as of 2013, has opened vast new possibilities for statistical analysis by recording every movement on the court.

A similar tracking system recently implemented by Major League Baseball has piqued the optimism of data-minded baseball writers too. “If we can get the exit speed of every batted ball, combined with the speed and angle taken by every fielder toward that batted ball, as easily as looking up someone’s batting average, that would be a game-changer from a media perspective,” said Grantland’s Jonah Keri.

Though reading stories filled with these statistics might seem like homework to some, including videos that illustrate the data is one way to both make it more appealing and drive home the argument the numbers are leading toward. In 2013, Keri’s Grantland colleague, Ben Lindbergh, used an array of GIFs to compare the defensive play of now-retired Yankees legend Derek Jeter to that of Brendan Ryan, a little-known shortstop who then played for the Seattle Mariners. The juxtaposed videos clearly support the stats, which suggest that, despite his award-winning reputation, Jeter was a terrible defensive shortstop. It’s a technique that can and should continue to be replicated.

Ben Lindbergh used this GIF to show beloved, but defensively challenged Yankees icon Derek Jeter reaching the maximum of his range to his glove side.

And he used this one to show Mariners shortstop Brendan Ryan reaching a ball that would’ve gotten past Jeter.

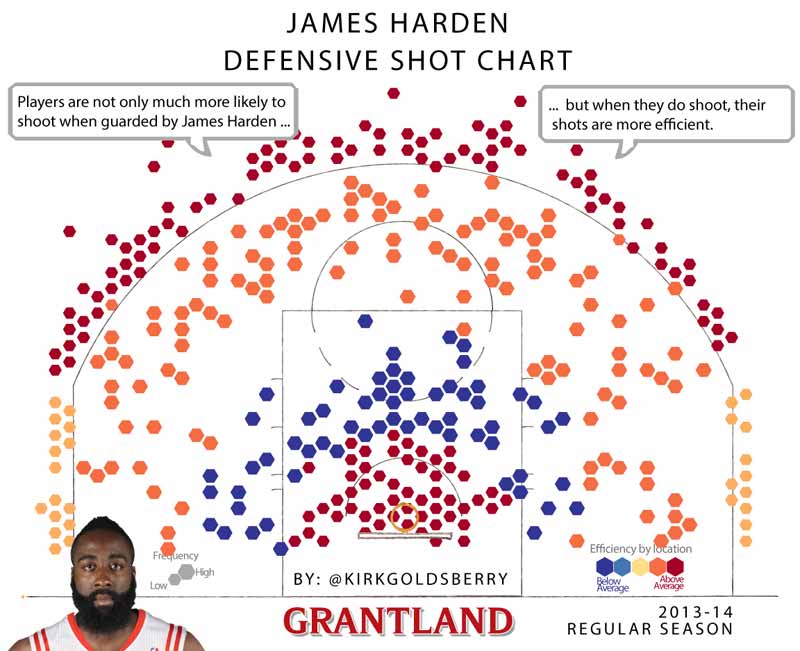

Yet another Grantland writer, Kirk Goldsberry, who is also a visiting scholar at Harvard and a member of Miller’s team, regularly uses both videos and statistics presented in colorful graphics to enrich the reader’s understanding of his words. While Goldsberry’s graphics usually act as visualizations of different players’ shooting abilities, he used the same method to display some of the defensive data studied by his colleagues.

Kirk Goldsberry used new data to create this graphic of James Harden’s defensive woes last season. The bigger the dot, the more Harden’s opponents shot from that space; the redder the dot, the more accurate they were.

While data-minded sports writers will no doubt use these and other ways of incorporating defensive numbers into their articles, the challenge of writing about defense is perhaps greater for writers who must not only explain, but also dramatize the events on the field or court.

Michael Lewis, whose famous book Moneyball brought the statistical revolution in baseball to the attention of the general public, attempted this feat in a 2009 New York Times Magazine story on then-Houston Rockets forward Shane Battier, a minimally skilled offensive player who used data to inform his excellent defense. The climax of the story is written from Battier’s perspective, as he guards the Los Angeles Lakers’ Kobe Bryant, one of the best scorers of all time, taking the winning shot. Lewis masterfully dramatizes Battier’s thought process, but the piece also demonstrates why fans and journalists are more inclined to focus on offense. Though Battier defends Bryant perfectly, the shot goes in anyway. “The process had gone just as [Battier] hoped,” Lewis wrote. “The outcome he could never control.”

Not being in control is a poor starting point for the kind of heroic narrative that has long animated sports writing. And it is noteworthy that the most revered defensive plays are those that involve a defender asserting control by showing up where he’s not expected, as in the cases of Willie Mays’ renowned catch and Malcolm Butler’s interception, which sealed this year’s Super Bowl for the New England Patriots. Butler anticipated where the Seattle Seahawks’ wide receiver would run and short-circuited his route with an aggressive (one might even say ‘offensive’) move to the ball. But much of the coverage of even that play, which will surely be remembered as one of the great defensive efforts in NFL history, surrounded whether the Seahawks’ coach had made a tactical error in calling for the quarterback to throw the ball rather than for a handoff to star running back Marshawn Lynch.

“People probably like defense in football more than in any other sport,” said Aaron Schatz of Football Outsiders, a football analytics site that partners with ESPN.com. “Offense is still more popular.”

An additional obstacle for football writers like Schatz is that football is lagging behind baseball and basketball in the realm of advanced statistics. Still, he told me, “It’s our job to use our English words where our numbers can’t go.” But no matter how engagingly journalists write or how thoroughly they quantify it, he does not believe that defense will ever spark the same enthusiasm as offense. “No stat,” Schatz said, “can overcome human psychology.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.