Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In nationally televised hearings, Senate Republicans denounce Voice of America. They accuse the government’s international broadcasting arm of harboring saboteurs, misspending taxpayer funds, condoning anti-Semitism, compromising security by relying on foreign-born workers, and denigrating the country it is supposed to serve. The committee chairman grills VOA executives, middle managers, and even copy editors, zeroing in on their alleged left-wing associations and on scripts and word choices that he deems un-American. “We intend…to detect duplications, waste, incompetence, subversion, in other words laying the entire picture on the table,” he proclaims.

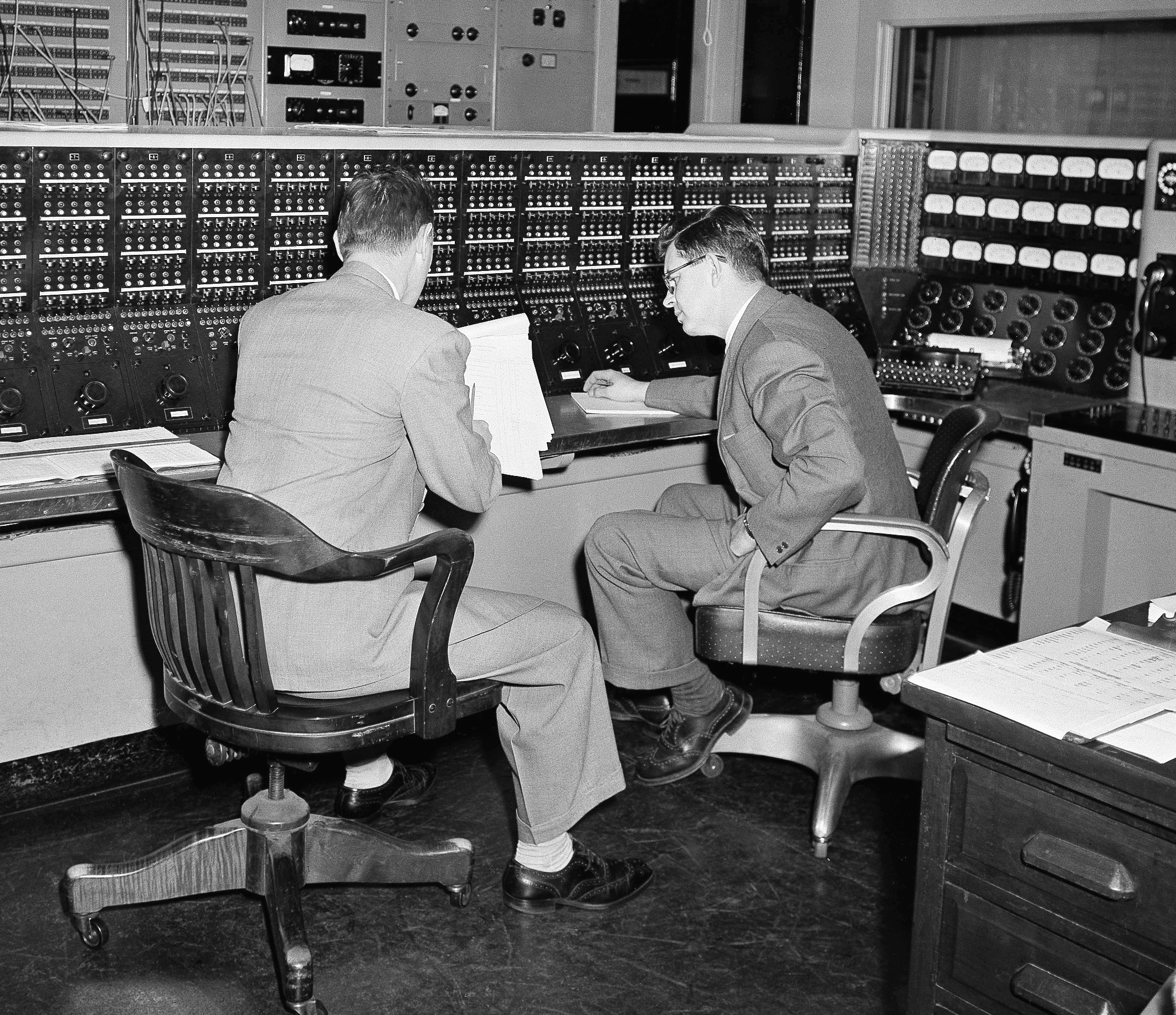

These hearings that gripped the country were not part of the Trump administration’s recent campaign against VOA. They took place in 1953, and the committee chair running them was none other than Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy, then at the peak of his power. Although his allegations were largely unsubstantiated, dread of his wrath was so pervasive that leaders of VOA’s parent agency resigned, numerous employees were fired, and an engineer killed himself.

Almost forgotten today, McCarthy’s VOA hearings—which lasted five weeks and included the testimony of sixty witnesses—represent an early and disruptive chapter in the eighty-three-year history of Voice of America. Despite VOA’s success, signified by its audience size—361 million people weekly worldwide as of February—and the efforts by past and present adversaries such as the Soviet Union, China, Iran, and North Korea to jam its signal, it has been a perennial lightning rod for domestic critics who preferred a more explicitly patriotic message. President Ronald Reagan purged key managers, and Trump tried to control its coverage in his first term before moving this year to silence what he has called “The Voice of Radical America” and reduce its staff by 85 percent. (Two federal lawsuits by VOA journalists are challenging the cuts.) The more than twelve hundred pages of transcripts of the McCarthy hearings reviewed by CJR have a remarkably contemporary feel, showing just how little the rhetoric surrounding Voice of America has changed.

At a June 25 congressional hearing titled “Spies, Lies, and Mismanagement,” Kari Lake, the Trump administration figure tasked with dismantling VOA, complained that it had strayed from its “glory days” during the Cold War, before it became “anti-American.” (Lake did not reply to emailed questions from CJR.) In reality, as early as 1947, a Republican congressman was already vilifying the network as the “voice of radical left-wingers,” according to The Voice of America and the Domestic Propaganda Battles, 1945–1953, by David F. Krugler. To McCarthy, it was the “Voice of Moscow.” “It was clear in McCarthy’s day, anything that was anti-Communist, true or not, he would applaud,” said McCarthy biographer Larry Tye. “That wasn’t true with one of the most effective of anti-Communist and truth-telling outlets, the Voice of America.”

What truly rankled VOA’s detractors—at the time and now—was the government-funded outlet’s journalistic impartiality, which dates back to its founding, in 1942, to counter Nazi propaganda. Its first broadcast to Germany began with a promise: “The news may be good for us. The news may be bad. But we shall tell you the truth.” Over the years, its independence was buttressed by firewalls—its charter, drafted in 1960 and enshrined in law in 1976, pledged “accurate, objective, and comprehensive” news coverage, and the International Broadcasting Act of 1994 protected it from political interference. “Some conservatives felt that the Voice of America should never say anything negative about the US,” said Senate Historian Emeritus Donald Ritchie. “The other side felt it had to present the news objectively. That debate has continued to the present day.”

Voice of America was one of McCarthy’s first targets after Republicans won control of the Senate in the 1952 elections, making him chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations and its permanent investigations subcommittee. Roy Cohn, the subcommittee’s chief counsel, who turned twenty-six during the hearings—and who decades later would mentor an up-and-coming real estate developer named Donald Trump—holed up in the Waldorf Astoria hotel in Manhattan and interviewed disgruntled employees from Voice of America’s New York office, according to Krugler’s book. Calling themselves the “Loyal Underground,” they fingered coworkers whom they suspected of Communist sympathies.

McCarthy manipulated the hearings, which began in mid-February 1953, to his advantage. He screened potential witnesses in executive sessions, weeding out the least compelling informants and antagonists. Then he leaked the highlights of these “dress rehearsals” to friendly reporters, according to Tye’s biography, Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy. McCarthy and Cohn questioned witnesses about petitions they had signed decades before, or dinners they had attended that had supposedly been sponsored by Communist fronts. One witness testified that a committee staffer had served him a subpoena in the middle of the night. “There was a pounding on the door and a ringing of the bell, which woke my children and terrified them in the time-honored Gestapo methods,” said Howard Fast, a left-wing author who had written news for VOA a decade earlier during World War II. NBC aired the public hearings on live television from 2pm to 4pm, according to Krugler.

All bluster to the contrary, McCarthy never found any spies in VOA. As the nation pivoted to face the Communist threat after World War II, many VOA employees had indeed been inclined to go easy on the Soviet Union, according to Nicholas Cull, a University of Southern California historian specializing in the role of mass communications in US foreign policy. But by 1953, years of political housecleaning at VOA had filtered out most of the leftists. “McCarthy didn’t expose any card-carrying Communists within VOA,” Cull said. “Instead, the people who are embarrassed are just socially different.” That included, for example, VOA’s director of religious programming. McCarthy accused him of being an atheist, and suggested he “might do a better job” if he “were a regular churchgoer.” The director—who had a doctorate in religion from Columbia, and had studied with the psychiatrist Carl Jung and the theologian Paul Tillich—testified that he did believe in God, and would not have taken the job otherwise.

McCarthy scrutinized Voice of America’s scripts and word choices as minutely as any proofreader. For instance, he wanted to know if an editor on VOA’s news desk—who had substituted “democratic” for “anticommunist” to describe crowds in Guatemala City cheering President Eisenhower’s inauguration—was “watering down” the dispatch because he was a Communist sympathizer. Denying the allegation, the editor said he used “anticommunist” often but changed it in this instance to capture the “spontaneous reaction by the Guatemalan people.”

McCarthy and Cohn also quizzed a cooperative witness who had worked in the VOA’s French-language service about a book review it aired of the novel Giant, by Pulitzer Prize winner Edna Ferber. According to testimony, the review reflected Ferber’s portrayal of Texas men drinking bourbon by the gallon, Texas women as “nitwits,” and Mexican servants living “harsh and difficult lives.”

“You feel we are doing a great service to the Communist cause in beaming this material out?” McCarthy asked.

“Yes, sir,” the witness replied.

McCarthy thanked him. “You are an example of the good people we have over on the Voice,” he said. “Thank God we have you and people like you over there, or the situation would be much worse.”

Many complaints about Voice of America were mundane and technical, but McCarthy enhanced them with a sinister mystique. He devoted much of the hearings’ opening sessions, in February 1953, to allegations by a former VOA engineer, Lewis J. McKesson, that the network was wasting millions of dollars by locating a transmitter station in the Seattle area, where atmospheric conditions would disrupt radio waves, rather than California. Days later, the government suspended the project, underscoring McCarthy’s influence.

Just as Lake has railed against “obscene overspending” at the US Agency for Global Media, which oversees VOA—for instance, accusing the agency of wasting hundreds of millions of dollars on a new headquarters—McCarthy assailed “reckless squandering” of public funding on the transmitter station. And just as Lake’s charges appear unfounded—Amanda Bennett, who headed USAGM when the headquarters lease was negotiated, responded in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that it would have saved more than one hundred and fifty million dollars had the Trump administration not canceled it—so too may have been McCarthy’s.

In reality, while the Washington site had some technical challenges, it may have been perfectly adequate for the job. The head of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology team that recommended it, Jerome Wiesner, who went on to become the school’s president, was never called to testify—possibly because, when Cohn preinterviewed him, he refused to repudiate his position.

“We do not know” whether the transmitter was “improperly located,” a New York Times editorial stated in March 1953, while deploring the “television carnival” of the hearings. “We do know that other experts have been willing to testify to the opposite effect, and they have yet to be called.”

Meanwhile, McCarthy repeatedly suggested, without evidence, that Voice of America’s leadership purposely picked the wrong location to undermine the battle against Communism. “We are involved not only in a question of waste of money but also in a question of subversion,” he said.

Even though Raymond Kaplan, the engineer who served as Voice of America’s liaison to MIT, was not asked to testify, the hearings dismayed him. On March 4, 1953, a day after telling a coworker that “the truth was distorted,” he threw himself in front of a truck in Cambridge. “Since most of the information passed through me, I guess I am the patsy for any mistakes made,” he wrote to his wife and son. “Once the dogs are set on you, everything you have done since the beginning of time is suspect.… I have never done anything that I consider wrong but I can’t take the pressure upon my shoulders any more.” Despite Kaplan’s note, and the medical examiner’s finding of suicide, McCarthy shrugged off responsibility, suggesting it was an accident or foul play.

Anticipating Lake, who accused Voice of America of refusing to identify the October 7, 2023, Hamas invasion of Israel as a terrorist attack—VOA’s actual policy was more nuanced, and did not prohibit calling the attack an act of terrorism—McCarthy tried to link the network with anti-Semitism.

The villain in his scenario was Reed Harris, the deputy director of the VOA’s parent organization, then called the International Information Administration. The senator asserted that a book Harris wrote more than two decades earlier—King Football, which criticized colleges for valuing sports over academics—was “acceptable to the Communists.”

Testifying first in executive session in February 1953 and then for three straight days in public in early March, Harris denied ever having been a Communist Party member or supporter, and said the FBI and other agencies had determined he wasn’t a security risk. But McCarthy contended that Harris had protected Communism by ordering in December 1952 that Voice of America close its Hebrew-language service. That service, the senator argued, reached Israelis who would have been outraged to learn of the executions of Jewish leaders in Soviet-dominated Czechoslovakia, after a show trial. “If I were trying to aid the Communist cause…one of the excellent ways…would be to cut off the Hebrew desk at the time they were handed this excellent counterpropaganda weapon,” McCarthy said.

Harris staunchly defended his directive. He said budget cuts forced difficult choices, and that more Israelis listened to the network in English than Hebrew. Voice of America, he said, was “stepping up, at the same time, the comments about the anti-Semitic activity of the Soviets and their satellites, and that news was getting into Israel very, very effectively.” In any case, the order to close the Hebrew desk had never even taken effect; Harris’s boss overruled him.

“I have the truth on my side, sir,” Harris told McCarthy. “I am going to stand behind it. And I am not afraid of my reputation, ultimately, in spite of any aspersions that are cast here.” Nevertheless, he soon resigned under pressure. Eight years later, his career would be rescued by Edward R. Murrow, the distinguished CBS journalist whose exposés of McCarthyism on his See It Now program contributed to the Wisconsin senator’s downfall, and who now, as head of VOA’s parent organization, rehired Harris as his executive assistant.

Murrow eloquently defended VOA against similar headwinds. At his 1961 confirmation hearing to run the agency, he told the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations that the service should report “the bad” about the United States along with the good, for the sake of its credibility. Homer Capehart, a Republican senator from Indiana who before entering politics had made his living by peddling everything from plows to popcorn machines, disagreed. He advised Murrow to “sell the United States to the world, just as a sales manager’s job is to sell a Buick or a Cadillac or a radio or television set,” without revealing “the weaknesses of their product.”

“We cannot be effective in telling the American story abroad if we tell it only in superlatives,” Murrow replied.

In 2003, half a century after McCarthy’s hearings, the subcommittee he had chaired released transcripts of the closed-door sessions. “Senator McCarthy’s zeal to uncover subversion and espionage led to disturbing excesses,” Senators Carl Levin and Susan Collins wrote, in what seemed at the time to be the final reckoning of the moment in history. “His browbeating tactics destroyed careers of people who were not involved in the infiltration of our government.… These hearings are a part of our national past that we can neither afford to forget nor permit to reoccur.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.