Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Hyperlinks are a powerful tool for journalists and their readers. Diving deep into the context of an article is just a click away. But hyperlinks are a double-edged sword; for all of the internet’s boundlessness, what’s found on the Web can also be modified, moved, or entirely vanished.

The fragility of the Web poses an issue for any area of work or interest that is reliant on written records. Loss of reference material, negative SEO impacts, and malicious hijacking of valuable outlinks are among the adverse effects of a broken URL. More fundamentally, it leaves articles from decades past as shells of their former selves, cut off from their original sourcing and context. And the problem goes beyond journalism. In a 2014 study, for example, researchers (including some on this team) found that nearly half of all hyperlinks in Supreme Court opinions led to content that had either changed since its original publication or disappeared from the internet.

Hosts control URLs. When they delete a URL’s content, intentionally or not, readers find an unreachable website. This often irreversible decay of Web content is commonly known as linkrot. It is similar to the related problem of content drift, or the typically unannounced changes––retractions, additions, replacement––to the content at a particular URL.

Our team of researchers at Harvard Law School has undertaken a project to gain insight into the extent and characteristics of journalistic linkrot and content drift. We examined hyperlinks in New York Times articles, starting with the launch of the Times website in 1996 up through mid-2019, developed on the basis of a data set provided to us by the Times. The substantial linkrot and content drift we found here reflect the inherent difficulties of long-term linking to pieces of a volatile Web. The Times in particular is a well-resourced standard-bearer for digital journalism, with a robust institutional archiving structure. Their interest in facing the challenge of linkrot indicates that it has yet to be understood or comprehensively addressed across the field.

The data set of links on which we built our analysis was assembled by Times software engineers who extracted URLs embedded in archival articles and packaged them with basic article metadata such as section and publication date. We measured linkrot by writing a script to visit each of the unique “deep” URLs in the data set and log HTTP response codes, redirects, and server timeouts. On the basis of this analysis, we labeled each link as being “rotted” (removed or unreachable) or “intact” (returning a valid page).

Two Million Hyperlinks

We found that of the 553,693 articles within the purview of our study––meaning they included URLs on nytimes.com––there were a total of 2,283,445 hyperlinks pointing to content outside of nytimes.com. Seventy-two percent of those were “deep links” with a path to a specific page, such as example.com/article, which is where we focused our analysis (as opposed to simply example.com, which composed the rest of the data set).

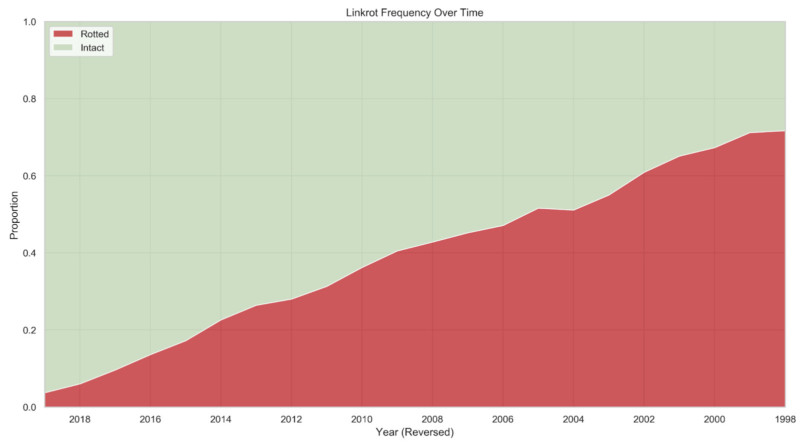

Of these deep links, 25 percent of all links were completely inaccessible. Linkrot became more common over time: 6 percent of links from 2018 had rotted, as compared to 43 percent of links from 2008 and 72 percent of links from 1998. Fifty-three percent of all articles that contained deep links had at least one rotted link.

Rot Across Sections

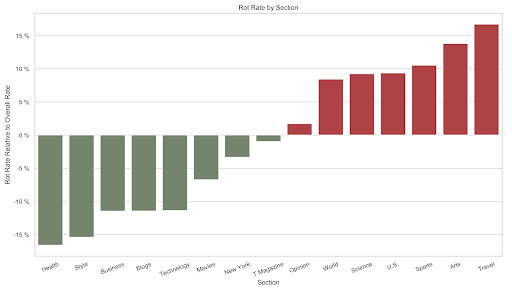

Certain sections of the Times displayed much higher rates of rotted URLs. Links in the Sports section, for example, demonstrate a relative rot rate of about 36 percent, as opposed to 13 percent for The Upshot. This difference has to do, in large part, with time. The average age of a link in The Upshot is 1,450 days, as opposed to 3,196 days in the Sports section.

To detect how much these chronological differences alone account for variation in rot rate across sections, we developed a metric, Relative Rot Rate. It allows us to see whether a section has suffered proportionally more or less linkrot than the Times overall. Of the fifteen sections with the most articles, the Health section had the lowest RRR figures, falling about 17 percent below the baseline linkrot frequency. The Travel section had the highest rot rate, with more than 17 percent of links appearing in the section’s articles having rotted.

A section that reports heavily on government affairs or education might be disadvantaged by the fact that deep links to domains like .gov or .edu show higher rates of rot. These URLs are volatile by design: whitehouse.gov will always have the same URL but will fundamentally change in both content and structure with each new administration. It is precisely because their domains are fixed that their deep links are fragile.

Content Drift

Of course, returning a valid page isn’t the same thing as returning the page as seen by the author who originally included the link in an article. Linkrot’s partner in content drift can make the content at the end of a URL misleading or dramatically divergent from the original linker’s intentions. For example, a 2008 article about a congressional race references a member of the New York City Council and links to what had been his page on the council site. Today, clicking on the same link would lead you to the district’s current council member’s website.

To identify the prevalence of content drift, we conducted a human review of 4,500 URLs sampled at random from the URLs that our script had labeled as intact. For the purposes of this review, we defined a link that had suffered from content drift as a URL used in a Times article that did not point to the relevant information that the original article was referring to when it was published. On the basis of this analysis, reviewers marked each URL in the sample as being “intact” or “drifted.”

Thirteen percent of intact links from that sample of 4,500 had drifted significantly since the Times published them. Four percent of reachable links published in articles from 2019 had drifted, as compared to 25 percent of reachable links from 2009.

The Path Forward

Linkrot and content drift at this scale across the New York Times is not a sign of neglect, but rather a reflection of the state of modern online citation. The rapid sharing of information through links enhances the field of journalism. That it is being compromised by the fundamental volatility of the Web points to the need for new practices, workflows, and technologies.

Retroactive options––or mitigation––are limited, but still important to consider. The Internet Archive hosts an impressive, though far from comprehensive, assortment of snapshots of websites. It’s best understood as a means of patching incidents of linkrot and content drift. Publications could work to improve the visibility of the Internet Archive and other services like it as a tool for readers, or even automatically replace broken links with ones to archives, as the Wikipedia community has done.

Still, more fundamental measures are necessary. Journalists have adopted some proactive solutions, such as screenshotting and storing static images of websites. But it doesn’t solve for the reader who comes across an inaccessible link.

New frameworks for considering the purpose of a given link will help bolster the intertwined processes of journalism and research. Before linking, for instance, journalists should decide whether they want a dynamic link to a volatile Web––risking rot or content drift, but enabling further exploration of a topic––or a frozen piece of archival material, fixed to represent exactly what the author would have seen at the time of writing. Newsrooms––and the people who support them––should build technical tools to streamline this more sophisticated linking process, giving writers maximum control over how their pieces interact with other Web content.

Newsrooms ought to consider adopting tools to suit their workflows and make link preservation a seamless part of the journalistic process. Partnerships between library and information professionals and digital newsrooms would be fruitful for creating these strategies. Previously, such partnerships have produced domain-tailored solutions, like those offered to the legal field by the Harvard Law School Library’s Perma.cc project (which the authors of this report work on or have worked on).

The skills of information professionals should be paired with the specific concerns of digital journalism to surface particular needs and areas for development. For example, explorations into more automated detection of linkrot and content drift would open doors for newsrooms to balance the need for external linking with archival considerations while maintaining their large-scale publishing needs.

Digital journalism has grown significantly over the past decade, taking an essential place in the historical record. Linkrot is already blighting that record––and it’s not going away on its own.

For an extended version of this research, as well as more information about methodology and the data set, visit https://cyber.harvard.edu/publication/2021/paper-record-meets-ephemeral-web.

Below, a list of archived citations included in this piece:

https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/the-dire-state-of-news-archiving-in-the-digital-age.php archived at https://perma.cc/FEW8-EBPH

https://www.searchenginejournal.com/404-errors-google-crawling-indexing-ranking/261541/#close archived at https://perma.cc/H23H-28CJ

https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/deansterlingjones/links-for-sale-on-major-news-wesbites archived at https://perma.cc/D6B3-2Z2A

https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/06/12/democrats-rally-around-mcmahon-in-si-race/ archived at https://perma.cc/W95N-U4S9

https://council.nyc.gov/district-49/ archived at https://perma.cc/QNZ6-SEXP

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.