Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

I do not know what Brandenburg was like in 1940, when the smoke and smell of the first burning bodies drifted across the town. But on a blue-skied day in May 2019, as I sat outside what was once the Brandenburg State Hospital, I was struck by the sounds coming in—the shrieks and laughter of children from a nearby playground washing over the remains of a place where Nazis killed at least nine thousand people.

It was the proximity that disturbed me, the fact that ordinary people had lived so close to such evil. The question that I would continue to ask myself over the two-week trip through Germany and Poland was: Why didn’t journalists do a better job of warning people, by giving them the information they could have used to act?

I was in Germany as a professor for Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics (FASPE). The fellows were early-career journalists, and we studied the ways the media covered the lead-up to the Holocaust and compared that to ethical issues that arise in covering the news today.

In 2019, there were some clear parallels between what happened in Nazi Germany and what was then happening in the United States under the first Trump administration: the scapegoating of groups of people, the disdain for the judiciary, the vilification of the press. There were similarities in how journalists covered those respective years, too.

American newspapers initially portrayed Hitler’s rise as just another political movement rather than a unique and existential threat. When Dachau opened, in 1933, the New York Times described it as an “educational concentration camp” for political prisoners, a “Nazi college” with “a vast, clean dining hall and a new big swimming pool.” Similarly, throughout Trump’s first term, many media outlets, including the Times, CNN, and the Washington Post, were accused of “sanewashing” his actions, thereby failing to give the public a true sense of the danger he posed to democracy.

Today the situation feels much more dire, and the media is, by and large, still failing to meet the scale of the threat he represents. During Trump’s 2024 campaign, NPR’s public editor Kelly McBride wrote, “Some listeners believe that NPR’s calm and steady approach is a bit too calm and steady.” One listener complained that NPR was treating Trump like a “normal” candidate when “HE IS NOT AND YOU KNOW IT!” The listener continued: “You are doing a great disservice to the American people, and if he wins the election you will be complicit.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about the discussions we had on the FASPE trip, and why journalists often fail to adequately convey danger at such crucial moments in history, including this one. I don’t know that journalists have fully grasped what our role needs to be in this moment. The veneer of neutrality embedded in institutional journalism is, I think, a constraint. The question is whether a profession that was founded to reflect the concerns of elites—property-owning white men—and helped shape public discourse in ways that protected their political and economic power has the mettle to meet this particular moment. Is it journalism’s job to fight against potential dangers, or merely to present the facts? Does boldly taking a stance somehow make our reporting less accurate?

As Marvin Kalb, founding director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, writes in Why Didn’t the Press Shout? American and International Journalism During the Holocaust: “In a craft that extols objectivity, how neutral, how dispassionate, can a journalist be?”

Journalism is often seen as the impartial dissemination of information. I would argue that the role of journalists is not to provide information in a vacuum, but to add context, history, solutions, and critical analysis so that the public truly understands issues and their implications. Kalb explains the distinction, made by Elie Wiesel, between providing people with information and equipping them with knowledge.

“Alone, information meant only the existence of data. It lacked an activist, ethical component. It was neutral,” Kalb writes. “Knowledge, implied Wiesel, was a higher form of information. Knowledge was information that had been internalized—crowned with a moral dimension that could be transformed into a call for action.”

This is what journalism must be now—not merely a mirror, but a moral force that actively resists the erosion of truth and democracy.

There is already a great deal of courageous journalism being done, but there are risks in challenging the Trump administration. President Trump has cut $1.1 billion in funding for public media. He has gone after individual journalists.

Even when reporters do stand their ground, Trump rarely engages in good faith. He dodges, deflects, lies, and often pivots to personal insults.

Covering this administration therefore creates a conundrum. But the insistence on neutrality makes it difficult to convey the full scope of danger this administration poses—not just to targeted groups, but to all Americans, even those who do not yet see it.

“Faced with what I and apparently you see as a danger to American democracy, does the journalist have a responsibility to say, ‘Hey, reader, hey, viewer, please, don’t you see this danger as I do, and shouldn’t we be doing something about it?’” Kalb said when we spoke recently. “In other words, the journalist becomes a fighter in a war, in a political war, and that violates everything that American journalism has represented.”

Ethnic media outlets have long understood that journalism is not just about informing the public, but equipping people to resist oppression. When your community’s survival is at stake, neutrality isn’t an option. When American newspapers eventually began reporting on the Nazis’ persecution and killing of Jewish people, those stories were often buried on the inside pages. In contrast, reporting in The Forward, a Jewish newspaper, very prominently and clearly named the atrocities: “Thousands of Jews in Poland are being gassed to death.… Masses of Jews, earlier described as deported to ‘unknown places,’ are in fact being executed in special ‘gas chambers’ in Nazi concentration camps.” The same can be said for the Black press. Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned newspaper in the US, was launched to resist slavery. The Chicago Defender called for the Great Migration. Ida B. Wells didn’t just report on lynchings, she risked her life to expose them and demand justice.

The Kansas City Defender covers systemic injustice with unapologetic clarity, embracing this history of Black press resistance. Founder Ryan Sorrell says that all news organizations report through a particular lens, even if they won’t admit it: “We are transparent about our agenda. And the New York Times, for instance, is not,” he said. “Anyone who says they are an unbiased media platform is not being honest.”

Sorrell believes that there are things legacy news organizations could learn from the Black press about how to cover this moment. “We’ve lived under fascism. We’ve lived under authoritarianism,” he says. He believes such organizations avoid clearly naming injustice because it would be bad for business. “A lot of corporate media’s primary audience is middle-aged or older white people. And because of that, it’s against their financial interest to say anything that would make them lose subscribers,” he said.

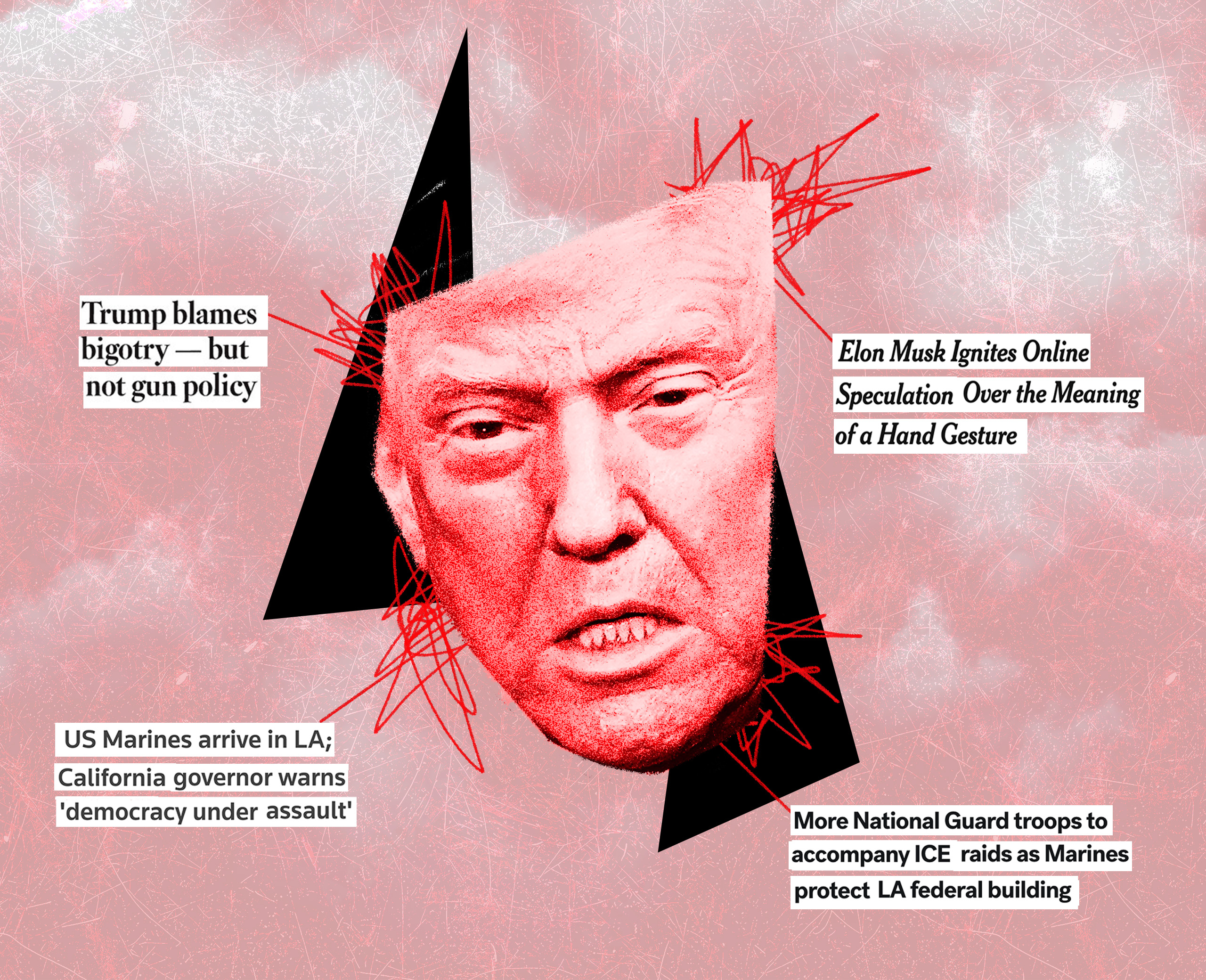

News outlets continue to use euphemisms and the passive voice rather than naming bad actors and their actions directly. The New York Times headline “Elon Musk Ignites Online Speculation over the Meaning of a Hand Gesture” felt, to many readers, and to me, like an effort to avoid the words “Nazi salute.” (That phrase is used in the dek.) In June, an ABC News live update of the military response to protests against Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids in Los Angeles read: “More National Guard troops to accompany ICE raids as Marines protect LA federal building.” Reuters reported, “US Marines arrive in LA; California governor warns ‘democracy under assault.’” While the articles themselves did include more details, and the words arrive and protect are accurate, these headlines do not capture the impact on civilians, use of martial power, or constitutional danger.

“We have to be willing to call the thing the thing,” said Martin G. Reynolds, co–executive director of the Maynard Institute. “A journalist’s job is to interrogate and find truth, and if the truth reveals itself to an issue being framed in a certain way, such as Trump being a felon, racist, and someone who seeks to willfully undermine the will of voters and the rule of law, we commit journalistic malfeasance if we cover him with a neutral framing.”

Bill Ong Hing, founding director of the Immigration and Deportation Defense Clinic at the University of San Francisco, argues that reporting on immigration should make clear that the system is racist, as the laws upon which detentions and deportations are based were made to keep immigrants of certain racial backgrounds out of the US. “The law doesn’t begin from a starting point that is racially neutral,” Hing said.

There have been moments where mainstream outlets have reported with a level of defiance in the face of democratic crisis. Washington Post reporter Murrey Marder was relentless in his coverage of Senator Joseph McCarthy, helping to expose that McCarthy’s claims about communist spies infiltrating the government were false. His reporting led to the first live televised congressional hearings in history, and McCarthy was ultimately censured by the Senate.

In his book The Powers That Be, David Halberstam writes of Marder: “Doggedly, he worked out a means of covering McCarthy. Hold him to the record. Not just what he said yesterday, but the day before and the week before. Explain not just this charge, but what happened to the previous charges.… Try above all not to be a megaphone for McCarthy. Expose him to maximum scrutiny.”

This is the kind of fortitude that is necessary today.

When the Associated Press was barred from attending White House press briefings earlier this year, other outlets should have walked out in protest. Newsrooms should stop quoting lies in the name of balance and simply say: This is false, and repeating it spreads disinformation. CNN and MSNBC set a good example in 2023 when they decided not to air Trump’s live remarks after his indictment. “As we have said before in these circumstances, there is a cost to us as a news organization to knowingly broadcast untrue things,” Rachel Maddow said, explaining MSNBC’s decision.

But those decisions are the exception. The broader media reluctance to take a firmer stance seems to often come down to one thing: money. Paramount’s recent $16 million settlement with Trump—reportedly to help smooth the path for an $8.4 billion merger requiring FCC approval—is one example.

“We find a shortage of that kind of courage,” Kalb said. “We find money—big money—determining editorial content.”

That financial incentive helps determine what gets covered, and how. President Trump understands how to exploit this dynamic, saying things that will generate attention and outrage. He knows that media companies will amplify his statements because they drive clicks, ratings, and revenue. But the real story is not in the outrageous, headline-grabbing thing that was said or done, but the impact.

The media landscape in the 1930s was in some ways similar to what it is today. The political leanings of newspaper owners determined the coverage. New technology was making journalism more accessible and engaging audiences in different ways.

“A lot of the owners of newspapers were rich Republicans, and newspapers were treading a fine line between satisfying their influential, rich Republican supporters and not driving away their ‘ordinary’ readers. And they didn’t do that well,” said historian and Columbia Journalism School professor Andie Tucher. “Meanwhile, radio is a new, exciting technology, like the internet. It feels responsive. It’s a voice.”

Radio reporting was immediate and conveyed emotion. It reached audiences that had previously been underserved—those who were illiterate, who could not read English, or who lived in rural areas and could not get newspapers delivered in a timely fashion. Radio also turned news consumption into a communal experience, in much the way that social media has today.

The big difference between the media ecosystem then and now, says Dickson Louie, who teaches a course in the business of media at UC Davis’s Graduate School of Management, is how fragmented news consumption has become. Legacy outlets have fewer resources to stand up to power, corporate consolidation has reshaped newsroom governance, and many Americans now get their news from social media.

Louie said that because mainstream media outlets serve such a broad audience, they will continue to report “both sides,” so to speak, “despite the administration’s deviations from traditional political norms.”

“Expect more original, critical, and activist news reporting to come from smaller news outlets or independent journalists now on Substack and other platforms,” he said.

Historian Heather Cox Richardson’s Substack is one of the most-read political newsletters in the country. She explains systems in a way that feels accessible, helping readers make sense of what’s happening. Media outlets need to offer this kind of context not just in news analysis, but in reporting, and should deliver news in ways people want it, engaging them not as passive consumers, but as partners. Several of my journalist friends have cited lengthy investigative articles that have exposed Trump’s malfeasance as examples of Marder-like courage. My question to them was whether those articles, while brilliantly reported, had reached the average American.

I’ve heard many people say they’ve stopped reading, listening to, or watching the news because it makes them feel overwhelmed, alarmed, and ultimately powerless. Journalism shouldn’t just inform, it should connect people to resources and others who are already organizing in their communities. This is where local and independent outlets often do what national newsrooms can’t: build relationships and foster solidarity. Their proximity to the communities they cover, and the trust they’ve built across divides, can be a conduit, not just for information, but for action.

The popularity of smaller, more nimble, and often more daring outlets reflects both the public’s hunger for something different and a sense that legacy media may no longer be structurally equipped to confront the challenge with which we are now faced.

History has shown the consequences of a press too reluctant to name the danger. How can journalism claim to be properly serving the public if it fails to act with urgency now? It’s a question I asked Kalb.

“You are grappling with the fundamental question confronting American journalism,” he said. “And the resolution of that issue will ultimately determine the state of democracy in this country.”

While the job of saving democracy does not rest on the shoulders of journalists alone, we have a critical role to play. We must abandon the myth of neutrality and report not just with the clear premise that what’s happening is dangerous, but the understanding that the systems enabling it are deeply entrenched. This will demand introspection and a willingness to practice a bold new kind of journalism that means putting our duty to the public above all else.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.