Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

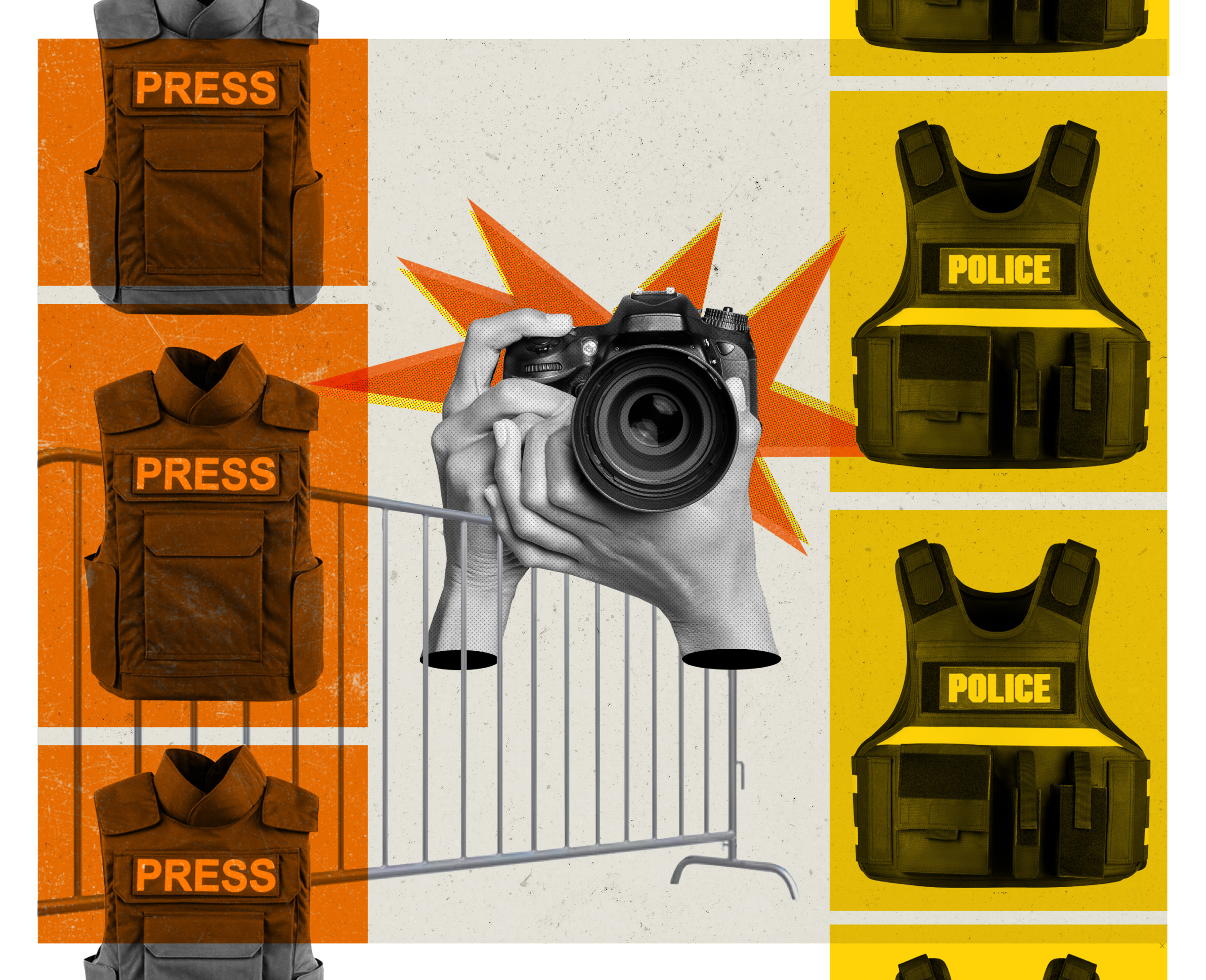

Last month, and just in time for what could be a historic season of protests and demonstrations before the presidential inauguration, the US Department of Justice released a first-of-its-kind report on best-practices recommendations for press-police interactions.

Drawing on a convening with newsroom leaders and police commanders from around the country, the forty-page document offers concrete, actionable recommendations like training officers to quickly release mistakenly detained journalists.

While not binding, the recommendations provide a solid framework to shore up protections for journalists covering protests, including on an issue that has confounded press advocates. That is, when police issue a lawful dispersal order permitting them to remove some individuals from the scene of a protest, can they do the same with journalists? Resolving that question in a way that protects newsgathering is a matter of paramount importance for journalists’ safety and public accountability. During the mass protests of 2020, for instance, there were an unfortunate number of detentions, arrests, and uses of force against journalists in the context of dispersal order enforcement.

The conventional wisdom on the question is that journalists have no “special” rights when it comes to their presence at mass demonstrations. As Chief Tom Manger of the US Capitol Police put it during the convening: “The media can be where the public can be, and the public can be where the media is at. That’s what the law says.”

The new DOJ report helpfully suggests that the law, in fact, may say something different.

First, it’s important to understand what we mean by a dispersal order. Although the laws differ in their particulars, every jurisdiction has various authorities to deal with civil unrest, or what the eighteenth-century British would come to colorfully call “King Mob.”

These include crimes like disorderly conduct, blocking public thoroughfares, trespass, interfering with a police officer, and curfew violations. They also include crimes specific to civil unrest, including the offenses of unlawful assembly (where the participants assemble with the intent to engage in some unlawful activity), “rout” (where the unlawful assembly takes some step to achieve that unlawful goal), and “riot” (where the assembly, well, riots). And in order to break up an assembly where unlawful activity is occurring, officers can order participants to disperse. If they do not, they can also be arrested for failure to disperse.

Further, in many of these cases, there need not be an imminent threat of violence or that one be involved in illegal activity to be liable for failure to disperse. It’s usually enough that the person is aware of the order and fails to comply.

Practically speaking, this means that when journalists are on the scene of a protest—even when they are off to the side, engaged in lawful newsgathering, and not interfering with police activities—they can be and have been swept up in dispersal order enforcement.

It is this use of dispersal orders that has prompted courts and other authorities to struggle with the question presented by Chief Manger above: Even assuming that journalists do not have special rights under the First Amendment, is there some legal rationale that would allow them to remain on the scene when officers have the authority to remove others?

The new DOJ best-practices report builds on a growing body of law and policy guidance suggesting that, indeed, there is. Further, those sources support the proposition that the “special rights” framing has always been a distraction, and the question of whether journalists may have protections under the First Amendment to continue reporting is better seen under the rubric of a more fundamental legal principle. That is, even when the government has the authority to restrict protest activity, whatever means it uses to do so must be tailored to address the underlying criminal activity justifying the restriction.

Among the authorities the best-practices report cites are an important federal lawsuit arising out of the unrest in 2020 in Portland, Oregon, called Index Newspapers LLC v. US Marshals Service, and the Justice Department’s own 2023 report in its civil rights investigation into the Minneapolis Police Department. It’s worth unpacking both in some detail.

The demonstrations in Portland were particularly intense and protracted. There were numerous confrontations between local police and protesters, and there were multiple clashes, one fatal, between protesters and counterprotesters.

In July 2020, the federal government deployed officers from several agencies, including Customs and Border Protection and the US Marshals Service, ostensibly to protect federal property. There were reports, however, of those officers roving farther into the city to detain, arrest, or use force against journalists and protesters.

A group of journalists sued both the city and the federal agencies, seeking a court order specifically exempting journalists and legal observers from being dispersed. The city agreed to refrain from doing so, but the federal agencies opposed the request.

The district court sided with the journalists and barred the federal agencies from arresting, threatening to arrest, or using physical force against anyone “whom [sic] they know or reasonably should know is a journalist or legal observer, unless officers have probable cause to believe the person has committed a crime.”

(Importantly, the court’s injunction required officers to take a “functional” approach to identifying journalists based on indicators including “visual identification as a member of the press, such as by carrying a professional or authorized press pass, carrying professional gear such as professional photographic equipment, or distinctive clothing, that identifies the wearer as a member of the press.” The court also said that it shall be an indicator of one’s press status “that the person is standing off to the side of a protest, not engaging in protest activities, and not intermixed with persons engaged in protest activities, though these are not requirements.”)

The federal agencies then appealed. The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ultimately upheld the district court and left the court order in place.

In doing so, the Ninth Circuit engaged with the federal agencies’ argument that prohibiting the dispersal of journalists would accord them special rights relative to the public. The Ninth Circuit not only disagreed but reframed the question along the lines noted above.

The court cited a seminal Supreme Court case from 1986 commonly referred to as Press-Enterprise II, which involved whether the state could properly close a preliminary hearing in a criminal trial. There, the Supreme Court recognized a right of access to such hearings, which can be overcome only on a showing that closure is “essential to preserve higher values and is narrowly tailored to serve that interest.”

Analogizing public access to the preliminary hearing to public access to streets and sidewalks, the Ninth Circuit agreed with the district court that the dispersal of journalists engaged in lawful newsgathering is not “essential or narrowly tailored” to serve the federal officers’ legitimate interest in protecting federal property.

In other words, the “special right” of journalists to remain on the scene is just the application of the basic First Amendment insight that restrictions on protected speech in public places must not suppress too much speech or do so unnecessarily. The Index Newspapers opinion also emphasized the importance of the press as a check on government and the need for independent coverage of the police response to protest activity to ensure accountability.

Additionally, the DOJ best-practices report cites the Civil Rights Division’s findings in its recent investigation into whether the Minneapolis Police Department engaged in a “pattern or practice” of constitutional violations. The MPD report notably included, for the first time, a detailed discussion of press rights violations. And it suggested the same answer to the special-rights question as Index Newspapers, but through a different legal lens.

The doctrinal question in Press-Enterprise II usually comes up in the context of reporters trying to access sealed court documents or closed proceedings, but the Ninth Circuit applied it to physically accessing public property.

There’s another area of First Amendment law that could apply, however, involving direct government limitations on speech in public places that have historically been dedicated to expressive activities, like sidewalks, parks, or the proverbial town square. There, the basic rule is that while you may have a right to protest in a public park, you can’t use a high-decibel sound cannon to do so at 3am.

To be constitutional, these “time, place, and manner” restrictions on speech must meet three conditions. They can’t be based on the content of the speech at issue. They must be narrowly tailored to serve a “significant” government interest. And, most important in the protest context, they must leave open “ample alternative channels” for the speech that is being restricted.

So, for instance, the Supreme Court in 1984 upheld a ban on sleeping overnight in Lafayette Park and the National Mall, even if done to raise awareness of homelessness. The court reasoned that the restriction was content-neutral, that it was narrowly tailored to serve the significant government interest in preserving the condition of the parks, and, crucially, that there were ample alternative means of communicating the intended message. In other words, even if you couldn’t stay overnight on the National Mall, you could still get the same message across reasonably well in another way.

Applying this time, place, and manner analysis to the dispersal of journalists, then, the key insight is that absent some protection for journalists’ ability to gather the news, the “blanket” enforcement of dispersal orders at protests can shut down newsgathering entirely. In other words, there is no alternative means of communicating the relevant information—in this case, the news—let alone an “ample” one.

In finding that the MPD had interfered with newsgathering by “unlawfully limiting journalists’ access to public spaces where protests take place,” the Civil Rights Division said as much. “Blanket enforcement of dispersal orders and curfews against the press,” the report said, fails to leave open “ample alternative channels” for gathering the news “because they foreclose the press from reporting about what happens after the dispersal or curfew is issued, including how police enforce those orders.”

The new DOJ best-practices report echoed that reasoning. It quotes the “blanket enforcement” language above. Further, it cautions that even in circumstances like the use of a dispersal order or enforcement of a curfew, where police may “reasonably limit public access,” police may need to “exempt reporters from these restrictions” to ensure that these limitations on access are “narrowly tailored.”

(We should note that the development of the DOJ report was supported by a grant from the department’s Office of Community Oriented Policing and authored by the Police Executive Research Forum, a nonprofit that specializes in policy development for law enforcement. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, where we work, helped bring together a convening last year of journalists and police that informed the report’s guidance.)

While the discussion above may seem academic, it is of great practical import for the working press. The “no special rights” refrain is a common defense in cases where journalists have sought to vindicate newsgathering rights, including in civil rights claims arising from detentions, arrests, or injuries at protests.

But the analysis above suggests that “no special rights” lacks nuance. Rather, the right way to look at the question is that each government restriction on each type of speech must be taken on its own terms. The government may be able to forcibly remove a high-decibel sound cannon from a public park at 3am, but can it block reporters from covering that police action?

In all cases, the First Amendment demands that, even when the government can lawfully restrict some speech, restrictions must be tailored to do as little harm as possible. And restrictions valid as to one type of speech may be invalid as to other types, even when they are occurring in the same general physical space and at the same time.

Additionally, what’s surprising about these developments is how they reflect a recent and evolving area of law. There just aren’t that many court cases looking at the question of whether the press may have a right to remain when other individuals can be removed. In part, this could be because mass, nationwide protest movements like we saw in 2020 are relatively rare. It is also because conventional wisdom has a tendency to be pretty sticky.

But if we can get the DOJ report and the material it draws upon in the hands of police departments and newsrooms around the country, we have a real shot at shifting the conventional wisdom and practices on the ground.

As the department’s report makes clear, it can’t be that the police can simply declare an assembly unlawful and shut down newsgathering entirely. Rather, while police can take targeted steps to address unlawful activity—including if journalists are breaking the law—“narrowly tailored” is the watchword. And that likely means that journalists who are covering protest activity and the police response to it have a First Amendment right to keep doing so, even when others present can be removed.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.