Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

While reporting on poverty in Appalachia for the Associated Press some years ago, I was walking a country road to the site of a grisly crime alongside two other reporters, a man from The Washington Post and a woman from a local broadcast station in West Virginia.

As we bantered, the woman sighed and said that she worried how the world would see her home state upon learning the crime involved a violent cocktail of drugs, abuse, and racial hatred.

She was woeful, saying something to the effect of “The rest of America already thinks we’re so backwards. Here’s another way we’ll be ridiculed.” My response at the time was a little cold: “The story isn’t about you; it’s about the story.” It was a variation on a thundering grad school lecture I’d heard from then-Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Jere Downs, who had pounded a classroom table with her heavy, practical shoe and repeated the phrase meant to offer us a personal code as reporters. She was warning us we’d have a lot of emotional and professional friction to navigate in newsrooms, that journalism is a human and flawed endeavor, and the only things worth focusing on are the truth, finding the best telling, offering the reader more than any other writer on your beat.

The West Virginian reporter nodded and went quiet with her worries; I felt a certainty in the maxim that seemed lost on her because the story touched a facet of her identity.

There are times when we see the world through journalism; there are times when we see ourselves through journalism. Other times we worry about how others will see us after they read a story.

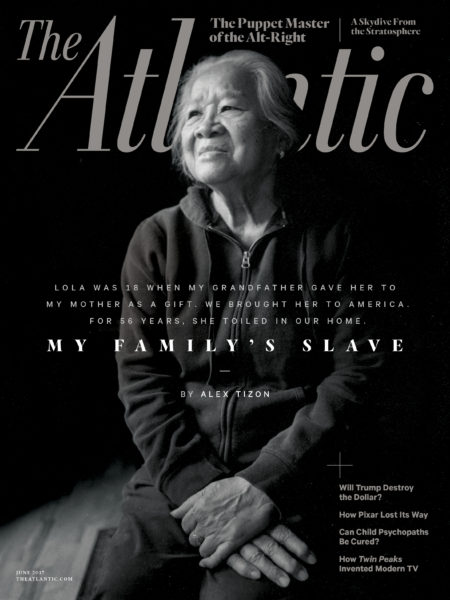

Alex Tizon’s essay “My Family’s Slave” in The Atlantic this week caused all the upheaval one has come to expect when that publication issues a detailed and gorgeously written cover story that dives into race, gender, and human rights. The publication has a long anti-slavery tradition—it was founded by abolitionists in 1857.

It is gripping to read the story of Eudocia Tomas Pulido, known as Lola, who toiled for Tizon’s family and sometimes fell asleep amid piles of laundry, who doted on children every day but was never a mother or a wife, and who never had a choice otherwise.

ICYMI: An interactive graphic that shows how much local news is suffering

Looking at responses on social media, it’s clear Tizon’s story offers readers a Rorschach test in which everyone seemed to see something different about the human condition and their own place, resulting in a broad and discordant range of responses.

The story reads like a portal into a taboo and secret world of unforgiving pain — a feat of journalism where slavery is revealed to be disquietingly banal and simple in its cruelties. It is an uneasy read.

For me, the story reads like a portal into a taboo and secret world of unforgiving pain—a feat of journalism where slavery is revealed to be disquietingly banal and simple in its cruelties. It is an uneasy read. You settle into the reality too quickly, even in your imagination. The sadness revealed in Tizon’s story is almost too big to comprehend, compounded by estimates there are more than 45 million people enslaved around the world today. That’s more people in unpaid servitude than there are living in my state of California. It is literally criminal what happened to Pulido and to others all over the world who toiled like her and who are toiling now.

Twitter responded with urgent calls to read this important piece—reminiscent of the attention Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Atlantic pieces have earned in the past—and questions about the ethics of this type of reporting and the behavior it revealed. Condemnations of slavery followed, where readers posed questions about what the author could have done sooner to free the woman (questions that will go unanswered; Tizon unexpectedly died before his story was published).

https://twitter.com/ItsTonyNow/status/864714601946116098

my favorite part of the slave article is the 'uhhh i guess i coulda turned my parents in but theyd probably like, get in trouble'

— raandy (@randygdub) May 17, 2017

Many leapt to condemn Tizon’s family—a somewhat meaningless echo considering how harshly he condemned himself and his parents, who he paints in the piece as dysfunctional and cruel.

Others dredged up the original obituary Tizon had placed in the Seattle Times, where Pulido is cringingly described as living “a life of devotion to family” though she was not kin and her devotion was involuntary. The obit’s original author, reporter Susan Kelleher, posted an explanation and condemnation of the lies she repeated unwittingly.

“In retrospect, the obituary reads as a whitewash for a fundamental truth known only to Tizon and his family: Ms. Pulido was a slave,” Kelleher writes, before offering apology.

TRENDING: Eleven newsletters to subscribe to if you work in media

For many others, particularly those in the Filipino community, the story offered a sort of funhouse reflection of a familiar culture of immigrants and the class structures of countries long departed and the secrets we all keep for fear of being misunderstood or reviled. For these readers the recognizable devotion of a woman who went by a moniker that means grandma was warped by the pain and dysfunction of Tizon’s family. Online, while many Filipinos condemned the slavery the story detailed, there was also sharp outcry about how their families and society were going to be perceived.

Concerns from readers of Filipino heritage ranged from objections to Tizon’s characterizations of slavery, to declarations their culture was under attack, to concerns the Filipino term for grandmother would be stained.

Would everyone’s Lola be mischaracterized as a slave?

https://twitter.com/TANGINART/status/864877695649239040

https://twitter.com/goldencircIe/status/864872469231919104

To these readers, I humbly submit: It’s about the story. It’s not about you. It’s not about your grandma, your parents, your slave. (Unless it is, and you have serious emotional labor to work through.) Or maybe this strikes close to home, to the servants your family kept, and the murky knowledge you have about their compensation and care; these are the conversations that were never had, the guilts that linger across generations without being understood.

Those feelings can inspire inter-generational conversations worth having, as Jay Caspian Kang’s piece on Medium demonstrates so well. Kang praises:

Tizon’s straight-forward style was all in the service of brutal honesty. That honesty transcends any of our literary or political categories. Perhaps more than anything I’ve read in recent years, it proved that any story can feel universal, even when it is about the most specific, and impossibly foreign things.

Kang’s note about universality is important because the article was meant for a wide readership, despite numerous calls for non-Filipinos to be wary of commenting on Filipino culture, for lack of understanding.

https://twitter.com/AtomSiraullo/status/864886345772130304

Americans expect us to condemn Alex Tizon right away because his family had a slave but they don't know shit about our culture

— millennial of manila (@MillennialOfMNL) May 17, 2017

But for any Westerner to fucking think they are better than us because they "abolished" slavery years ago needs to wake the fuck up.

— Not Mix (real) (@_todayiswendy) May 17, 2017

The article struck a chord with a broad readership precisely because slavery is universal, and has deep roots in the US. Pulido’s case comes at a time we’re still trying to untangle the brutality of the trans-Atlantic slave trade from our prison industrial complex that has overpopulated cells with descendants of those slaves.

Understandably, some black readers objected to the soft-lens focus of Tizon’s writing, and the defenses of Filipinos making cultural arguments for Pulido’s servitude.

https://twitter.com/dtwps/status/864870045033299969

Others recoiled at reactions that avoided addressing slavery.

https://twitter.com/Wokieleaksalt/status/864846218022793216

Diagram of the people finding cultural nuance in the domestic slave story & those who come from rich immigrant families who also own slaves pic.twitter.com/B2bsJ41wB2

— Will 🦥 Menaker (@willmenaker) May 17, 2017

Liberals: "IDENTITY 👏 POLITICS 👏 ARE 👏 IMPORTANT."

*story about modern slave*

LIberals: "SOME 👏FAMILIES👏 ARE 👏DIFFERENT👏 AND👏 THAT'S👏 OKAY."— Jezzer, Mean Gay Era (2001-present) (@Jezzerat) May 17, 2017

To expect a restrained response for such a tale, in the interest of cultural sensitivity, is to assume a level of dispassion that is unrealistic. No one should be asked to read Tizon’s unexpected confession of servitude, abuse, and emotional cataclysm with a generosity of spirit that the author himself did not exhibit.

In one long thread—a popular way to respond to the story—journalist Sarah Jeong dove into the relationships of the story, redefining them in ways Tizon did not.

The piece isn't about the conflicting emotions of a slave-owner, it's about how much Tizon hates himself and how much he loves Lola.

— sarah jeong (@sarahjeong) May 17, 2017

Jeong calls for reading Lola as a third parent, and the underappreciated mother who Tizon actually loved instead of his own mom. In Jeong’s reframing, Lola is like many wives the world over—toiling and suffering in silence through feminized labor and emotional support, for no pay.

This to me is a dangerous spinning of what Tizon took pains to portray in great detail. Tizon didn’t call Pulido his mother. To do so after his death is a loose reading at best, a disrespectful recasting of the painful reality at worst. If Jeong identifies a love that Lola didn’t feel and Tizon wasn’t able to give openly for decades, is that love real?

ICYMI: Journalists, here’s what to do “when things start to get genuinely bad”

Beyond the unquestioning devotion that slavery and motherhood both demand—a cutting observation of Jeong’s—there are some major differences between wifery and slavery. No one got down on one knee to ask Pulido if she was willing to enter a lifelong pact of servitude. She was not courted nor wooed, nor offered tokens of love and devotion. She loved the family she cared for, till death did her part, but served the vow Tizon’s grandfather committed her to unwillingly—earning a paltry $800 a month later in life when Tizon urged her to retire. She never had a life of her own—she never lived on her own, or married, or had children of her own. And tragically, as Tizon revealed, she never lost her virginity.

She was never married nor loved in the way any wife deserves to be. And, importantly, she had no opportunity for divorce.

Lastly, Pulido was in a country where she had human rights that went unprotected. Whatever the cultural argument within a family, slavery was made illegal in the United States with the 13th Amendment in 1865. Tizon’s family knew it—they hid Pulido in plain sight, avoiding questions of neighbors and any doubts that may have lived in their own hearts. Tizon feared deportation of his family if the arrangement was discovered.

Yet, I understand the protective reactions of Filipinos who read Tizon’s story with dread, better than I understood the reaction of that reporter in West Virginia.

Some threads that began as condemnations of the piece, and tipped into excruciating tellings of what tore other Filipino families apart and redefined them, creating behaviors of avoidance and saving face.

https://twitter.com/RinChupeco/status/864827849722576897

Even vocal critics of the piece had to make concessions in their cultural defenses.

https://twitter.com/AtomSiraullo/status/864888298845609984

Cultural pride and shame blend clumsily but often. I understand intimately the truth of the concern here: When audiences see people of color in their worst light, it confirms the least-educated and most fearful inclinations some had about the culture. That raises concerns about how such an article will change the way people think about Filipino families. As an Iranian-American, the response reminds me of the horror my parents felt when they watched Not Without My Daughter, the Sally Field movie based on Betty Mahmoody’s story of her abusive Iranian husband. Years later, I was stunned when a friend’s parent asked me if my dad was abusive—my father, the pacifist who rarely raised his voice, and never a hand. I can understand the utter dread of how Pulido’s story will alter the American psyche. I can understand wanting to stage a defense of the Filipino family now.

But there is no defending slavery, not after reading the details of the way Pulido was dehumanized and ripped from her home and country to be demeaned and abused for decades. That is the conclusion that Tizon must have come to before penning the most personal condemnation of slavery we may ever see from a slave owner.

ICYMI: 11 images that show how the Trump administration is failing at photography

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.