Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In July, Eitan Fischberger got an email from an Israel Defense Forces spokesperson asking if he wanted to go to Gaza. Fischberger, who is thirty-one, is a former air force technician in the IDF who publishes a Substack called Fisch Files—where, as he told me, he critiques media outlets for failing to do “genuine journalism with integrity.” Recent posts include “Keep the New York Times out of Gaza,” “Hamas-Tied ‘Journalist’ Agrees to Stage Famine Scene for Cash,” and a piece that references a Palestinian journalist who was killed in a targeted Israeli attack: “Meet Anas al-Sharif’s Replacement at Al Jazeera: He’s Also a Member of Hamas.” Raised in New York and New Jersey, Fischberger moved as a child with his family to Efrat, a settlement in the West Bank. He has since amassed more than fifty-three thousand followers on X and regularly appears on Israeli podcasts and news shows as a pundit. Now, suddenly, he had a chance to do some reporting of his own.

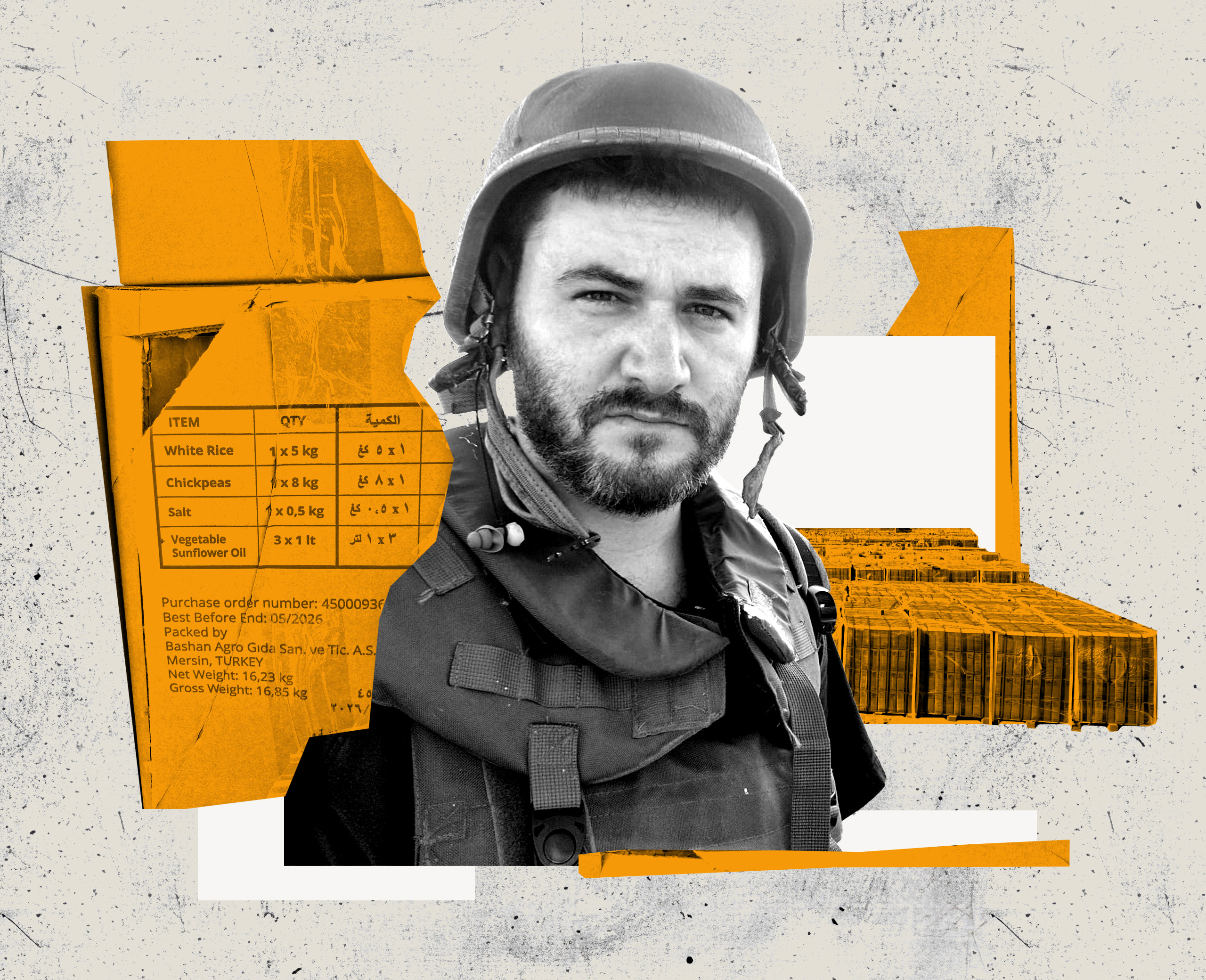

A few days after receiving the email, he drove to Kerem Shalom, a crossing on the Gaza-Israel border—the name translates as “Vineyard of Peace”—where military officers handed him a bulletproof helmet and a flak jacket and drove him across. “Three, four minutes, twists and turns, and we saw what we saw,” Fischberger told me. On a wide expanse of concrete sat pallet after pallet of supplies earmarked for Gaza: cooking oil, flour, bags of rice, tomato paste. Also around him were content creators bearing selfie sticks and filming on their phones.

The trip was one of a handful of recent delegations organized by various arms of the Israeli government, including the Diaspora Affairs Ministry, aimed at winning the media war—that is, countering the proliferation of reliable reports that Gazans have been suffering amid genocide and famine. Public perception of the circumstances among people in the United States, given its sway over peace negotiations, has proved to be critical, and Israel has focused its attention on content creators with American reach: in addition to Fischberger, invitations have been extended to Noa Cochva, a former Miss Israel now living in New York; Xaviaer DuRousseau, a MAGA booster; and a spirituality influencer who goes by Jeremy Awakens. “Weapons change over time,” Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, said during a recent meeting with influencers in the US, and “the most important ones are on social media.” He highlighted the role of TikTok and X, in particular. The Diaspora Affairs Ministry has claimed that messaging from trips coordinated by its office has “reached over fifteen million views within just a few days, reinforcing Israel’s position against Hamas’s smear ‘starvation’ campaign” and underlining the “critical role” of “influencers and content creators” in “exposing this lie to millions worldwide.”

Fischberger and his fellow content creators have been granted privileged access to Gaza, where Israel has blocked international media, save for occasional embeds with the IDF. Journalism organizations have clamored to get in—as expressed in an open letter from June coordinated by Reporters Without Borders, calling this “a situation that is without precedent in modern warfare.” Local reporters have faced threats, discrediting of their work, and hunger; press freedom groups estimate that some two hundred have been killed. (The IDF did not respond to requests for comment.)

That day at Kerem Shalom, Brigadier General Effie Defrin, the IDF’s chief spokesperson, “gave his spiel,” Fischberger said, putting blame on the United Nations for failing to distribute aid. Defrin also made clear that anything posted online would first have to be cleared by the IDF, “in the case that I accidentally filmed something that could jeopardize operational security.” Fischberger didn’t have a problem with that. “I am very open about my biases,” he told me. “I love my country. I generally trust the IDF.”

Israel’s PR crisis of the moment revolved around aid: humanitarian organizations were accusing the country of severely curtailing distribution, and the UN found that more than a thousand Gazans had been killed by Israeli forces while coming to collect supplies. Fischberger held his phone to his face and started recording. He addressed one video to Cindy McCain, the executive director of the UN’s World Food Programme, asking why she wasn’t delivering the aid behind him: “Is it because you could, God forbid, make Israel look good?” He clambered up on some pallets to pan over what he said was six hundred trucks’ worth of supplies; he posted the video on X with the caption “View from the top of Mt. Aid in Gaza.” Fischberger’s clips looked similar to those of his fellow creators who, in video after video, filmed themselves on their phones as they walked past pallets and declared that they were revealing the truth about Israel’s delivery of aid to Gaza. The uniform message: Israel was providing the aid, but the UN and other organizations were failing to deliver it.

For most of the influencers at the scene, the coverage ended once they headed home. But as Fischberger’s videos circulated online, he successfully pitched an op-ed to the Wall Street Journal. The resulting piece, “Gaza Starvation Photos Tell a Thousand Lies,” condemns the failings of aid organizations, not Israel: “food meant for children,” he writes, “is left to rot.” He elides the exact nature of the trip, writing only that he embedded with the IDF, and he is identified as “an American-Israeli journalist.” (The Journal declined to comment on the editorial process.)

Not long after Fischberger and I spoke, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported that an Israeli-American firm called Bridges Partners LLC had filed a disclosure under the Foreign Agents Registration Act stating that it had been hired by the Israeli government to recruit and pay influencers to “assist with promoting cultural interchange between the United States and Israel.” Through a campaign called the Esther Project, the Israeli government would allocate Bridges up to nine hundred thousand dollars to find and compensate willing influencers. Responding to the news on his Substack, Fischberger wrote, “Let’s be clear: every single country tries to influence the United States, and they all use influencers to do it.” He told me that neither Israel nor Bridges Partners had paid him to visit Kerem Shalom and joked that he had, in fact, lost money paying for gas.

As for his Kerem Shalom videos, Fischberger said that anyone who doubted their validity after learning of the Esther Project is “just looking for a reason to try and delegitimize them.” When I asked if he considers his work to be propaganda for the IDF, Fischberger firmly rejected the categorization. “People can call me a propagandist,” he replied. “I’m just describing reality as I see it.” Of the IDF, he said, “if they’re manipulating me” into spreading a certain message, “they’re doing a really good job of it. I don’t even notice it at all.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.