Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

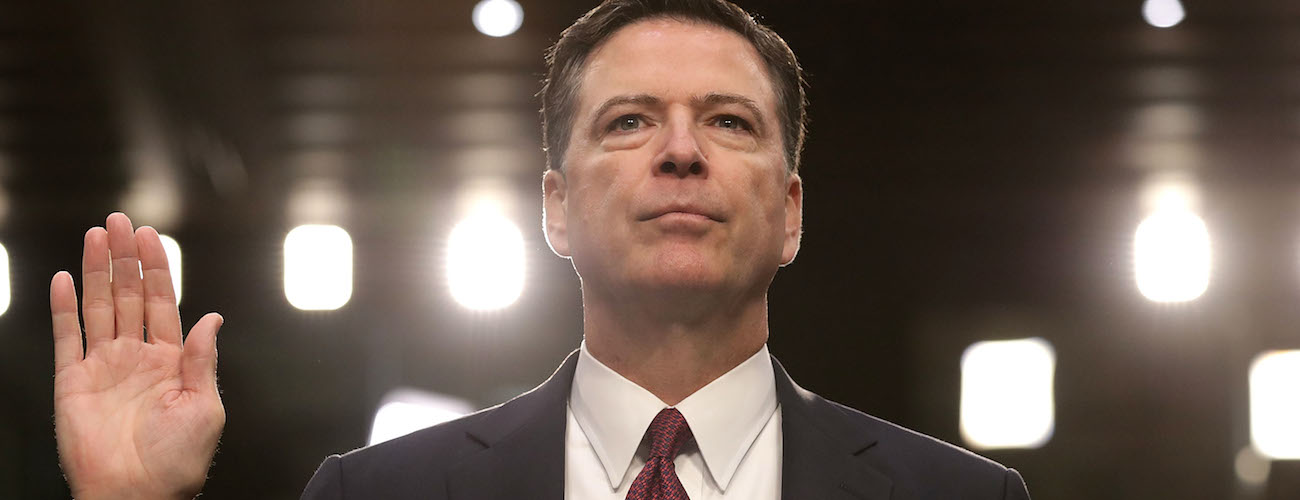

When the Senate Intelligence Committee released prepared testimony by fired-FBI Director James Comey on Wednesday, it appeared to confirm much of the bombshell reporting in the scoop war roiling Washington over the past month. The planned statement, it seemed, vindicated journalists’ aggressive investigation of the Trump campaign’s potential ties to the Kremlin and the nascent administration’s subsequent bungling of the matter.

But the two-and-a-half hour hearing in the Hart Senate Office Building on Thursday muddled that emerging narrative. The media-savvy Comey explicitly disputed a high-profile February New York Times report of alleged contacts between Trump aides and Russian intelligence, adding general criticisms of the media’s methods and accuracy during a lengthy cross-examination by elected officials.

RELATED: A hidden message in memo justifying Comey’s firing

The remarks have already become a central plotline in the right-wing media narratives emanating from Comey’s high-stakes public testimony, yet another snapshot of the ideologically bifurcated realities that have come to dominate the country’s political conversation. What’s more, fairly or not, they’ll fuel the anti-press line of attack emerging as a central plank of the Republican Party’s 2018 midterm strategy.

The episode is a harbinger of what’s to come throughout this administration and beyond, as pro-Trump voices latch onto occasional media slipups to discredit all other reporting, while offering no attempts at accountability journalism of their own. Comey, meanwhile, managed to convey both skepticism of and admiration for the mainstream press, reinforcing his image as an independent operator.

His most specific media criticism came during an exchange with Republican Senator Jim Risch, of Idaho, who inquired about the February 14 Times story alleging that Trump associates had repeatedly communicated with Russian intelligence officials during the campaign. Citing four unnamed sources, the Times reported that American officials had intercepted phone calls between the parties just as the FBI investigation into Russian meddling was heating up. White House officials tried to shoot down the story after its publication.

On Thursday, Risch called the report “not true,” adding to Comey, “Is that a fair statement?” The former FBI director responded:

In the main, it was not true. And, again, all of you know this, maybe the American people don’t. The challenge — and I’m not picking on reporters about writing stories about classified information — is that people talking about it often don’t really know what’s going on. And those of us who actually know what’s going on are not talking about it. And we don’t call the press to say, ‘Hey, you got that thing wrong about this sensitive topic.’

Not yet satisfied, Republican Senator of Tom Cotton, of Arkansas, returned to the Times piece, asking, “Would it be fair to characterize that story as almost entirely wrong?” Comey again answered in the affirmative.

“As we have said previously, we believe in the accuracy of our reporting,” a Times spokeswoman told CJR in a statement. “Our reporters are currently looking into Mr. Comey’s statement about our story and we plan to report back as soon as we can.” (The Times recently eliminated its public editor, an in-house critic dedicated to getting answers in such situations.)

ICYMI: Two dozen freelance journalists told CJR the best outlets to pitch

Later in Thursday’s hearing, Republican Senator James Lankford, of Oklahoma, posed a broader question about media accuracy: “Have there been news accounts about the Russian investigation, about collusion, about this whole event—or accusations—that, as you read the story, you were stunned about how wrong they got the facts?”

“Yes,” Comey responded. “There have been many, many stories purportedly based on classified information—about lots of stuff, but especially about Russia—that are just dead wrong.”

Lankford didn’t follow up about which supposed revelations were inaccurate, leaving the open-ended critique on the table. It was a savvy political decision from a senator whose party has made charges of “fake news” central to its rhetoric. Meanwhile, pointed questions established Comey as one of the leakers on whom the GOP constantly harps. In response to Republican Senator Susan Collins, of Maine, Comey admitted that he gave memos of his meetings with Trump to a friend with the express intent to share them with journalists. Not only did Comey criticize reporters on center stage, but he also did so despite conceding his friendliness toward their cause.

ICYMI: Here’s what non-fake news looks like

This narrative contrasts starkly with the journalistic chest-thumping on Twitter Wednesday night, after Comey’s prepared testimony dropped online. The written statement seemed to confirm many of the dueling New York Times and Washington Post reports that captivated the political world in May, from Trump leaning on Comey to drop the FBI’s investigation of his former national security adviser, to Trump’s demand for loyalty, Comey’s plea to not be left alone with the president, and more.

None of those stories was refuted, yet the Trump camp and Trump-friendly media have already seized on the Comey hearing to delegitimize all reporting on the inquiry. In the first sentence of a statement Thursday, Trump’s personal lawyer said Comey’s testimony ran “contrary to numerous false press accounts” about the FBI investigation into Russian meddling.

Right-wing outlets have followed suit, with a headline on the Breitbart homepage calling the hearing a “media bellyflop.” In Fox News’s immediate analysis, Bret Baier called the media one of the day’s big “losers.” A Republican National Committee Twitter account has since circulated the video clip.

Pro-Trump outlets have struggled to retain their audiences in the Trump era, as mainstream competitors have published scoop after scoop that suggest either White House malevolence or incompetence. Still, they collectively draw a huge following, fracturing the media ecosystem amid intense political polarization. With so many of these outlets remaining in lockstep alongside a president under fire, it’s unclear whether any amount of good reporting can break through their iron curtain of obfuscation.

ICYMI: The New York Times politics reporter who tweets like it’s going out of style

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Senator Tom Cotton represents Alabama.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.