Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

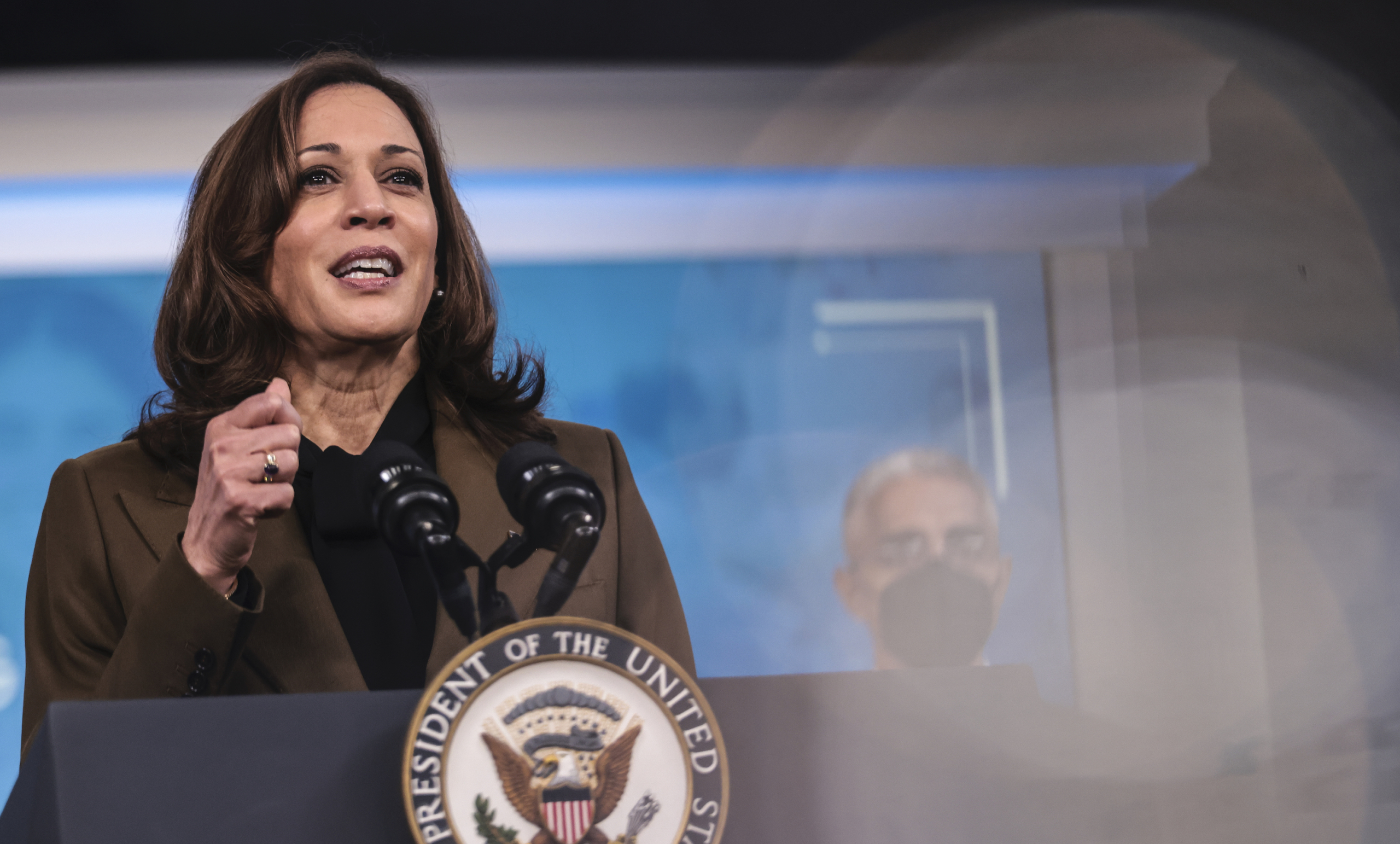

On Thanksgiving in 2019, Kamala Harris, then a candidate for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, found herself in the midst of a brutal news cycle. The Washington Post reported that her campaign was floundering as she struggled to define herself, while the New York Times reported on disarray among her staff. Politico referred to these together as “two nail-in-coffin stories” for Harris; less than a week later she was out of the race, leading allies (and even one presidential rival) to accuse the media of sexist and racist double standards in coverage of her campaign. Two Turkey Days later and Harris, now the vice president, could perhaps be forgiven for thinking it’s Groundhog Day, amid a fresh barrage of unflattering coverage. Last week, CNN dropped a mammoth piece—headlined “Exasperation and dysfunction: Inside Kamala Harris’ frustrating start as vice president”—suggesting, among other things, that she’s struggling to define herself and that her staff is in disarray; her allies again see a double standard. On Thursday, Harris went on ABC where she defended her record and denied that she feels “misused or underused,” as her interviewer George Stephanopoulos put it. On Friday, she won better headlines as she became the first female president of the United States—a position she held for roughly eighty-five minutes, while President Biden was under anesthesia for a colonoscopy.

Unlike in 2019, Harris is not currently running a presidential campaign, though you might not necessarily know it—indeed, the explicit undercurrent of much of her recent bad press has been the state of her presidential prospects for 2024, with questions swirling as to whether Biden really intends to run again and whether, if he doesn’t, Harris is his “heir apparent.” This coverage has assessed Harris’s political standing both in relative isolation (her approval rating is bad) and vis-à-vis other Democratic contenders, hypothetical or otherwise. (“Science Concludes Kamala Harris Would Be One of Worst Possible Democratic Presidential Candidates,” a headline in Slate concluded, based on one survey.) Of the latter, much has been made of Harris’s supposed rivalry with Pete Buttigieg, who, as transportation secretary, is enjoying a moment in the media spotlight tied to Biden’s infrastructure legislation. Per Politico, Buttigieg’s recent “positive press” has grated on “Harris-world.” On Meet the Press on Sunday, Chuck Todd asked Buttigieg if the “rivalry” narrative had strained the pair’s relationship; Buttigieg replied that it hadn’t because neither is paying attention to “what’s obsessing the commentators.” The press has assessed Buttigieg’s political prospects in their own right, too: the Post’s Toluse Olorunnipa, for instance, noted on CNN on Sunday that Buttigieg currently has a “nice portfolio” that he can use to talk up Biden’s infrastructure achievements and the bipartisanship that led to them. (“It’s obviously way too early to be talking about 2024,” Olorunnipa said, “but I’m going to talk about it anyways.”)

From the public editor: CNN’s tabloid tendencies

The political media’s recent 2024 speculation has not been limited to Harris and Buttigieg. High-ranking politicians can scarcely set foot in Iowa or New Hampshire without setting it off. The names of several other Democrats who ran in 2019—Amy Klobuchar, Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren—have been mentioned, as have the names of several who didn’t. Last week, CNN’s Erin Burnett asked Stacey Abrams, the leading Georgia Democrat, about a Politico article suggesting that she might run, calling the question “a crucial point”; Abrams demurred, saying that she’s currently focused on fighting to pass federal voting-rights legislation. (“We can have a conversation about elections after we do the work of protecting the democracy that undergirds those contests,” Abrams said.) Also last week, Biden tapped Mitch Landrieu, the former mayor of New Orleans, to coordinate infrastructure spending. A couple of hours after that news broke, Jonathan Martin, of the Times, tweeted, based on a text he’d just received from a Democratic source, that we should all “add another name to the 2024 roster”—though Vanity Fair has since argued that Landrieu’s appointment “could be interpreted as a strategic move” on Biden’s part to “shutter speculation” that he’s actively positioning Buttigieg as his heir.

Such speculation isn’t just rampant on the Democratic side: for months now, reporters and pundits have been throwing around names on the Republican side, too, mooting everyone from Ron DeSantis, the media-bashing Florida governor, to Larry Hogan, the Maryland governor who is a fixture on mainstream news networks, where he has repeatedly been asked about his 2024 ambitions. Numerous journalists suggested that Glenn Youngkin might run in the hours after he was elected governor of Virginia this month, even though he’s never held office until now. Chris Christie recently told CNN’s Dana Bash that he doesn’t know yet if he’ll run (“The idea of making predictions for 2024 is folly,” he added); Mike Pence, NBC told us, recently gave a “campaign-like speech.” Donald Trump, of course, has loomed particularly large, generating what feels like at least as much 2024 chatter as every other potential candidate combined, on both sides. Last week, Bill Maher told CNN that Trump will definitely run again; yesterday, Michael Cohen told CNN that Maher is “absolutely wrong” in what was Cohen’s first interview since his release from his Trump-induced house arrest. The Washington Examiner’s David M. Drucker already wrote a book, titled In Trump’s Shadow, about the 2024 GOP primary, which he expects to be contested.

If you were to think that all this presidential talk is even earlier and even more feverish than the early, feverish media norm, then you wouldn’t be the only one: as the AP’s Steve Peoples put it on Sunday, in an article full of presidential talk, “the mere existence of such conversations so soon into a new presidency is unusual.” These conversations aren’t just happening among media pundits; loose-lipped politicians and donors are having them, too, and are driving a lot of the press coverage as a result, especially when they’re willing to put their names on the record. More broadly, the early speculation has been intensified by factors including Biden’s supposed recent political misfortunes (not least the Virginia election), his age (he turned seventy-nine on Saturday), and the apparently widespread assumption in Democratic circles that he never intended to serve two terms anyway. As the coverage has amped up, Biden’s aides have briefed out that he will run again, driving yet more coverage. Yesterday, Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, put her name behind that claim in a conversation with reporters on Air Force One.

Still, the media bears some responsibility for amplifying all this—no one is forcing us to cover 2024 already. Why is the media talking about this?! debates sometimes take on an all-or-nothing quality, rather than weighing proportion and prominence. The biggest problem with horse-race election coverage, arguably, isn’t that it exists at all, but that it overrides so much else of substance in major outlets’ attention spans. By that token, it could plausibly be argued that, while the 2024 chatter is already a big story, it isn’t (yet) the big story, and that there’s enough space across the media landscape for it to coexist with other big stories. (Olorunnipa talking about 2024 on CNN, for instance, came at the very end of the network’s Inside Politics show on Sunday, after a brief segment on Biden’s pardoning of two Thanksgiving turkeys.)

Still, any amount of top-level media attention is a precious resource, and there are hundreds of stories in the world right now that merit more coverage than an election that’s three years away. More to the point, even if you think the horserace should be a preeminent story, that distant timeframe—and everything that could change in the interim—makes much of the current chatter more or less obsolete, something commentators sometimes seem to acknowledge before chattering away regardless. For now, focusing on 2024 to any meaningful extent risks undercutting, and even distorting, the more important story of what Biden is doing in the present by implicitly lame-ducking him. Some aspects of the 2024 race are immediately newsworthy; as I’ve written often in this newsletter, the Republican war on elections is one of those. But even there, we must strike a balance with governance. That’s the point of elections.

Below, more on politics and democracy:

- Kamala Harris, I: Last week, Harris’s communications chief, Ashley Etienne, stepped down; Vanity Fair’s Abigail Tracy reported that Etienne had always intended to stay in that post for a year, “but still her departure comes after a raft of stories on infighting and low morale in the vice president’s office.” Some observers have blamed certain Harris aides for the poor coverage; some have blamed Harris herself. Rebecca Katz, a progressive strategist, told Tracy that the intense coverage of the insurrection derailed Harris’s moment in the spotlight earlier this year, by (rightfully) taking “all of the soft media off the grid.” Stories about Harris’s pathbreaking vice presidency “never really happened in the degree that they would have if our country wasn’t in such a scary place.”

- Kamala Harris, II: Writing for TheGrio, the political commentator Reecie Colbert argues that the media narrative that Harris has been invisible is both false and insidious. “Competence is, frankly, too boring for the media, so it resorts to gossip rag and premature horse race coverage of the next presidential election,” Colbert writes. At the same time, “Harris seeking a more prominent profile would be frowned upon in the West Wing, and lambasted by the same ‘invisible’ peddling critics as too ambitious.”

- “Backsliding”: Yesterday, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, a think tank based in Sweden, added the US to its list of “backsliding democracies,” the first time the country has ever appeared there; in a report, the group described Trump’s lies about the 2020 election as a “historic turning point.” The report captured significant media attention. “You will notice that the Washington Post chose to illustrate the story with a photo” of the insurrection, Chris Hayes said on MSNBC. “That day, of course, is the most striking example of our democratic backsliding. But this report reflects something deeper that is happening in our political culture.”

- Personality and politics: Writing for Scientific American, Asher Lawson and Hemant Kakkar, two researchers at Duke University, shared their finding that political ideology isn’t a sole determinant of whether a person is likely to share fake news—personality matters, too. Lawson and Kakkar found that “low-conscientiousness conservatives” have a “general need for chaos” and an “exceptional tendency to share fake news,” and are also less likely to heed fact-checking warnings appended to stories on social media.

Other notable stories:

- Alden Global Capital, the cost-slashing hedge fund that is already the second-biggest owner of local newspapers in the US, is now moving to acquire Lee Enterprises, which owns nearly a hundred papers including the Richmond Times-Dispatch and the Buffalo News. Alden, which already holds a six-percent stake in Lee, is offering twenty-four dollars per share, an increase of thirty percent on Lee’s closing share price last week.

- Bloomberg’s Gerry Smith and Lucas Shaw profiled The Athletic, a sports site that is exploring a sale and new ways to grow after realizing that subscription revenue alone “only goes so far.” After the pandemic hammered live sports, The Athletic laid off nearly fifty staffers, and the site has also scaled back its video and podcast output, Smith and Shaw write. Bosses are hoping that podcast and newsletter ads will help grow revenue.

- Reporters at Gizmodo, which was part of a consortium of news sites that was recently granted access to a trove of leaked documents from inside Facebook, are working to make “as many of the documents public as possible, as quickly as possible.” The site plans to work with a group of independent experts to establish guidelines for publication; their ranks include Priyanjana Bengani, a Tow Center researcher and CJR contributor.

- Ariana Pekary, CJR’s public editor for CNN, writes that the network is pushing ever further “into the realm of tabloid-like material” as it confronts a post-Trump decline in ratings. “This trend emerged in September with the death of Gabby Petito,” Pekary writes; since then, CNN has aired exaggerated coverage of inflation and paparazzi footage of Alec Baldwin, after he was involved in a fatal shooting on the set of a movie.

- In a highly unusual move, a judge in New York recently restrained the Times from seeking or publishing certain documents related to the right-wing site Project Veritas, which is suing the Times for defamation, and an appeals court confirmed the decision. The Times is now asking the Supreme Court of Westchester County to remove the restraint; yesterday, fifty press groups and news outlets backed the paper in a brief.

- Earlier this month, Adnan Kivan, a construction mogul, abruptly fired the entire staff of the Kyiv Post, an English-language paper that he owns in Ukraine, a decision that was widely interpreted as an assault on the paper’s editorial independence. Now thirty of its former staffers are launching the Kyiv Independent, a new English-language outlet that will be funded primarily by readers and donors rather than “a rich owner or an oligarch.”

- A few weeks ago, Paul Dacre, the former editor of the Daily Mail, a right-wing British tabloid, left his role as chair of Associated Newspapers, the Mail’s parent company. Since then, Dacre withdrew himself from contention to lead Britain’s media regulator (despite being the government’s favored candidate) while the Mail’s current editor (whom Dacre had publicly criticized) was ousted. Dacre is now back at Associated Newspapers.

- Fernando González, the AP’s Cuba-based news director for the Caribbean and Andes, has died following a heart attack. He was sixty. “Gregarious and seemingly inexhaustible, González, known for his trademark long gray ponytail, was especially strong and compassionate in crisis situations,” the AP’s John Rice writes, “both covering the news and tirelessly organizing help when colleagues were ill or injured.”

- And hackers took over the Twitter feed of the Dallas Observer, a newspaper in Texas, and used it, Vice reports, “to push an increasingly common scam: offering a hard-to-find PlayStation 5 console for sale on the social network.” Twitter temporarily restricted the account, while the Observer confirmed that it was “not offering sweet deals on PlayStation 5 consoles. We play on a gaming laptop and use Steam.”

ICYMI: The Kyle Rittenhouse trial, the media, and the bigger picture

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.