Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On Saturday, after months of local and national media speculation, former TV businessman Donald Trump endorsed former TV doctor Mehmet Oz for an open US Senate seat in Pennsylvania. Oz’s campaign to this point had not been smooth sailing—the Philadelphia Inquirer refused to call him “Dr.” Oz, which they called a commitment to fairness and he called an attempt to “cancel” him; local activists spurned him; he recently sounded off to a Bloomberg reporter in a restroom about the media’s supposed failure to scrutinize his main rival, David McCormick—and so the endorsement looked like a boon. Trump initially supported Sean Parnell in the race, but Parnell withdrew after his estranged wife, who had accused him of spousal and child abuse, was granted custody of their kids; Sean Hannity, of Fox News, was reportedly among those who lobbied Trump to back Oz in Parnell’s stead. “When you’re in television for eighteen years, that’s like a poll,” Trump said, referring to Oz’s background. “That means people like you.”

Trump’s decision quickly attracted a barrage of media coverage and takes. (Rolling Stone’s headline: “Fraud Endorses Quack.”) This was not a surprise—for months now, but particularly with the midterms heaving, tediously, into view, the Beltway press and outlets beyond have obsessed over Trump’s hyperactive endorsement strategy in everything from key congressional primaries to the race for Georgia’s insurance and fire safety commissioner. (The dogcatcher joke was getting tired, after all.) In recent weeks, in particular, one overarching narrative has dominated coverage in major outlets: that the upcoming primaries in which Trump has endorsed will constitute a major test of his political strength. “Is Trump’s hold on the GOP waning?” ABC News asked, representatively, last week. “We’re about to find out.” Some commentators aren’t even waiting for the results to come in. Axios’s Mike Allen already concluded—with reference to Parnell dropping out and Trump rescinding his endorsement of Mo Brooks for US Senate in Alabama—that each time a Trump-backed candidate fails, “his aura fades as GOP kingmaker.”

ICYMI: The war crimes beat

Such articles have often described the very real phenomenon of Republican primary candidates jockeying slavishly for Trump’s support—which many of them clearly see as being of enormous potential benefit—and the referendum-on-Trump framing of his endorsements would seem to have at least some merit in high-profile races where he is gunning loudly for a sworn foe: the gubernatorial election in Georgia, for instance, where incumbent Brian Kemp stood minimally in the way of Trump’s attempted coup, or the US House race in Wyoming, where incumbent Liz Cheney has become Trump’s most vocal GOP critic. Even these races, though, are subject to a web of complex dynamics involving multiple candidates. And this points to a much broader problem: that the Trump-endorsement obsession, at its worst, is priming the press to draw overly generalized national conclusions from elections where a messy array of specific local factors are at play. “We’re all America First people,” an activist told Politico recently after Trump made an odd endorsement in a North Carolina US House race, “but we don’t need Mr. Trump or anybody else bringing candidates in who don’t know nothing about farming, don’t know anything about agriculture and the roads here and the needs we have.”

The Trump-strength-test narrative has other pitfalls, too, that point to a broader pattern of oversimplification. First, there are limits to what even a clean sweep of embarrassing primary defeats for Trump-endorsed candidates would tell us about his standing in the Republican Party right now, let alone what it might portend for a possible Trump presidential run in 2024. Sure, such an outcome would offer insight as to what issues animate Republican voters the most at that moment. The idea, though, that it would decisively herald Trump’s irrelevance is misguided. Trump-endorsed candidates have lost primaries before, including at moments when his influence was indisputably high; in 2017, for instance, he backed Luther Strange over Roy Moore in a US Senate primary in Alabama, and we all remember how that one turned out. And election years that feature Trump’s own name on the ballot are simply different from those that don’t. The average voter is likely tracking endorsements less closely than the average pundit.

Second, the direction of causality is muddled here: while some candidates might win because Trump endorsed them, it’s clear in other cases that he is endorsing candidates because he thinks they’ll win. Trump is a notoriously sore loser and has not hidden his desire to have his name associated with likely winners, either in the past (see Strange, again) or the current election cycle. He framed his Oz endorsement explicitly in terms of popularity. (“When you’re in television for eighteen years, that’s like a poll.”) When he dropped Brooks, he said that it was because the latter had gone “woke” over the 2020 election, but many pundits traced the decision to the fact that Brooks was floundering in the polls, as Brooks (sort of) did himself, quipping in a radio interview that Trump might go on to endorse all three major candidates in the race because “that way, he’s assured of being able to say that he won.” There is an obvious trap here for the press. It’s clearly in Trump’s interests for the media to report that his influence over the Republican Party remains strong. If he tees up endorsements that he thinks will send that message, then reporting that his influence remains strong clearly plays into his hands.

Well, reporting that his influence remains strong on the basis of endorsements—because the third, and most important, point here is that Trump’s influence over the Republican Party is still strong, and there are much easier and more pertinent ways of reporting this clear fact than the overinterpretation of messy local races. As I wrote recently, the question of Trump’s grip on the GOP seems to be of endless fascination to political reporters and pundits who routinely seize on minor acts of supposed defiance to theorize that it might be slipping. Zoom out, however, and the big picture is abundantly clear; the Republican Party as an institution is so in the thrall of Trump and Trumpism that most of its representatives either endorse or will not debunk his dangerous lies about the last election, and a few faulty endorsements don’t seem likely to change that. Indeed, in many races—including Oz’s in Pennsylvania—candidates Trump hasn’t endorsed sound just as Trumpy as the Trump endorsee, if not more so. Would these candidates winning really constitute a defeat for Trump? On paper, maybe. But not in practice.

Endorsements can be an indicator of political influence. But they are one among many, and should not be driving this much coverage. In the end, our obsession with them looks like one more iteration of a broader Trump fixation that political media has yet to kick. To the extent that members of the press are limbering up to draw misleadingly neat, if not outright false, conclusions from messy data points, it’s dangerous. Even if the eventual conclusions end up aligning with other indicators of Trump’s strength, to focus on them is ultimately to center horse-race-style journalism at the expense of other, far more urgent stories about Trump’s power. Election denialism—and the fact that so many candidates feel they have to spout it to get Trump’s approval—is a more important story than these elections themselves.

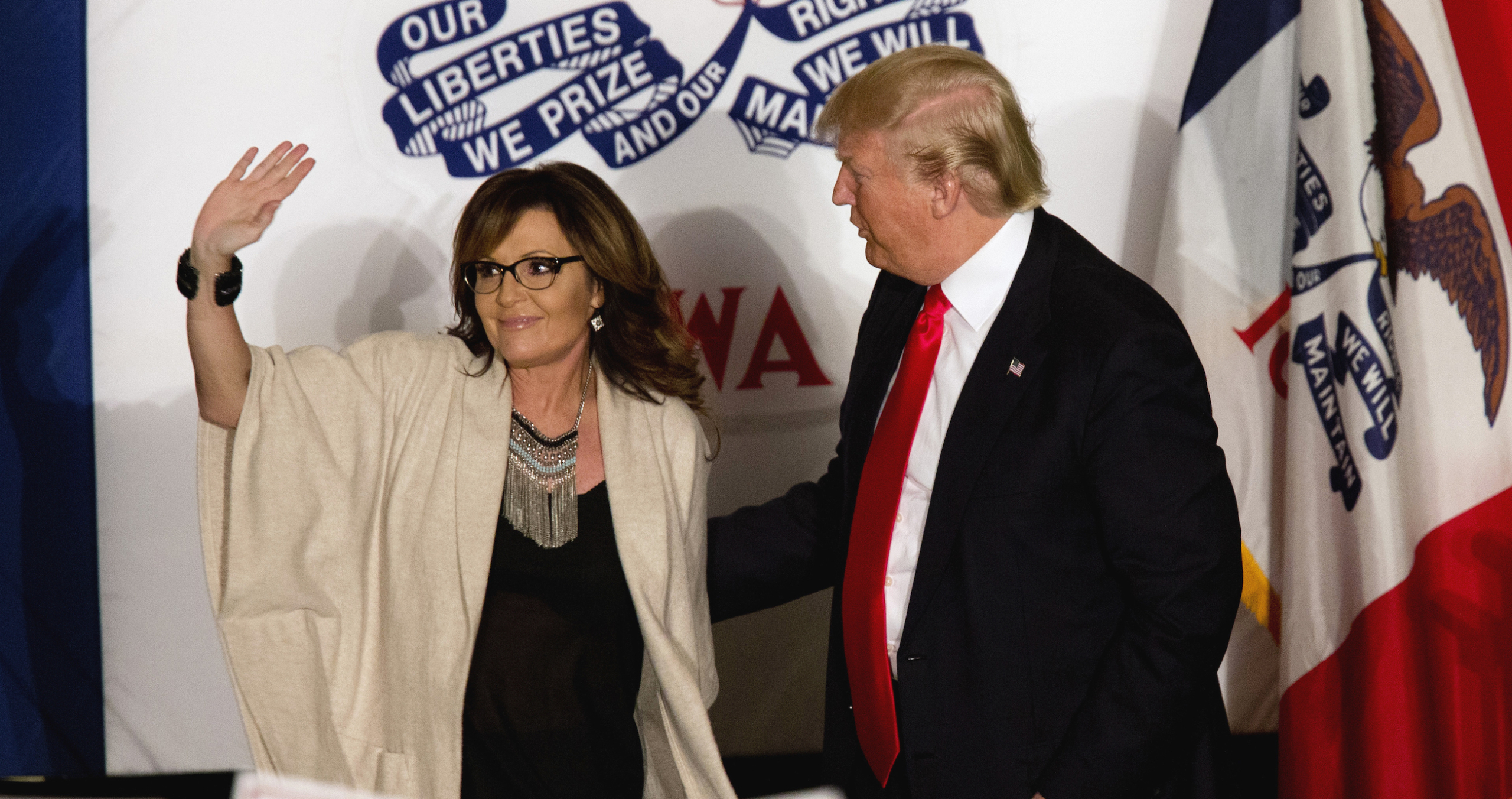

To the extent that the recent Trump-endorsement story can remind us of anything useful, it’s that while Trump has taken the Republican Party in frightening new directions, he’s built on an existing bedrock. One endorsement that has recently been touted as a test of Trump’s strength was that, last weekend, of Sarah Palin, the former Republican vice-presidential nominee and unsuccessful New York Times litigant who is running for Alaska’s open congressional seat. Palin, in many ways, was the ur-Trump; indeed, in 2016, she was perceived as giving him a boost when she became one of the first prominent Republicans to endorse his first presidential bid. As Trump put it when he returned the favor last week, “Sarah shocked many when she endorsed me very early in 2016, and we won big. Now, it’s my turn!”

Below, more on Trump and the midterms:

- What the polls say: New survey data from Morning Consult suggests that Trump’s favorability rating remains very high among Republican voters in states with key midterm races coming up, “raising questions,” Eli Yokley writes, about what the fate of Trump’s endorsed candidates “actually portends for his grip on the party.” One Republican operative told Yokley that while we judge Trump “very differently from every other president, for obvious reasons,” he doesn’t have control over all the factors that decide individual races. “It’s one thing to say, ‘Trump is popular,’” another operative noted, “and quite another to say, ‘voters will do whatever they are told every time.’”

- King of kingmakers: Trump’s endorsements were clearly on his mind when he sat down last week with the Washington Post’s Josh Dawsey. “He sought during much of the interview to tout his political supremacy inside the Republican Party,” Dawsey writes. “Unprompted, he decried news coverage that indicated otherwise and crowed about how many people wanted his endorsement, while vowing to stop the Republicans who favored impeaching him.” At one point, Trump claimed that Viktor Orbán, the recently reelected prime minister of Hungary, had called to thank Trump for endorsing him. “I’m the king of endorsements,” he said. “It’s more than just this country. It’s other countries.”

- Restroom with a view: Joshua Green’s recent Bloomberg profile of McCormick and the Pennsylvania Senate race is worth a read, not least for its Oz restroom interview. “When Oz comes bounding out to greet the audience a few minutes later, he sticks to familiar culture-war themes, blasting vaccine mandates and Dr. Anthony Fauci and complaining that the media is trying to cancel him,” Green wrote, of what happened next. “Oz, it should be said, is a more convincing vessel of Trumpian grievance than McCormick—wild, frenetic, slightly unhinged, and always attentive to the campaign cameraman, who mirrors his every move like a duet partner.”

- Enough already: For CJR’s recent issue on political journalism, Kyle Pope, our editor and publisher, took aim at the media’s ongoing Trump fixation, arguing that we blew an opportunity to refocus after Biden took office. “If the insurrection foiled our initial shot at a new, Trump-free approach to covering politics, the instincts of the press doomed it,” Pope wrote. “The pace of White House coverage eased, as did reporters’ fixation on the presidency, yet Trump remained a character in major stories.”

Other notable stories:

- Carlotta Gall and Daniel Berehulak, of the Times, have a sickeningly detailed account of Russian atrocities in the Ukrainian town of Bucha after spending more than a week there with city officials, coroners, and scores of witnesses. (ICYMI, I wrote about the war crimes beat in yesterday’s newsletter.) Elsewhere, Vladimir Kara-Murza, a prominent Kremlin critic, was reportedly detained in Moscow, hours after giving an interview on CNN+. The German outlet Welt hired Marina Ovsyannikova, the then-staffer who spoke out against the war on Russian state TV last month, to report from Russia and Ukraine, with one Putin ally now arguing that she should lose her citizenship. And Novaya Gazeta journalists who fled Russia have launched a new outlet called Novaya Gazeta. Europe.

- Christian Smalls and Derrick Palmer, who recently won a stunning victory in a union drive at an Amazon warehouse on Staten Island, appeared on the Times’ Daily podcast to explain how they did it. At one point, Smalls reflected on his media strategy around a planned worker protest early in the pandemic. “I knew the media wasn’t gonna come if I would have said five people” were going to show up, he said. “So, of course, I lied. I said it might be two hundred people outside. And I knew that it wasn’t going to be, but I checked the weather, I played chess, it was going to be sixty degrees”—warm enough, in other words, for workers to be eating lunch outside. The press turned up en masse.

- Politico’s Max Tani and Allie Bice profiled the American Prospect, a liberal magazine that is having a moment under Biden, recalling the days “when left-leaning magazines like The New Republic, The Nation, or Mother Jones were heavy hitters in Democratic D.C. power circles.” The White House requested copies of a recent issue on the supply chain, with one reportedly ending up in the Oval Office; across the aisle, Senator Lindsey Graham asked Biden’s Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson if she has any ties to the Prospect (she doesn’t) after it ran articles scrutinizing Graham’s favored pick.

- In TV-news news, Rachel Maddow returned to her MSNBC show after a two-month hiatus and announced that, starting next month, she will only host it on Mondays, with rotating hosts filling in for her the rest of the week. Elsewhere, Leigh Ann Caldwell, who covers Congress for NBC News, is joining the Post, where she’ll coauthor a morning newsletter and lead interviews for its video-streaming site as the paper leans into different journalistic formats. And the CNN+ streamer is finally now available on Roku.

- In media-business news, Kaiser Health News announced a slate of hires for its new rural health desk, which will start up later this month. Elsewhere, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting awarded a six-hundred-thousand-dollar grant to help Code Switch, NPR’s show about race and identity, “expand its presence on radio and through live and virtual events,” Current reports. And the New Jersey Hills Media Group is going nonprofit.

- Cory Doctorow takes issue with a global wave of bills aimed at forcing Big Tech to pay publishers for their content, arguing that creating “a licensable right to talk about the news” is bad, and that unrigging ad markets is a better idea. “The problem isn’t Big Tech stealing publishers’ content,” he writes, “it’s that Big Tech is stealing publishers’ money.”

- The Guardian, which is currently free to read across most of its digital platforms, will test putting its app behind a metered paywall, the Financial Times reports. One Guardian journalist described the paper’s changing stance on paywalls as welcome but “surreal.”

- Step aside, Hollywood Unlocked: Brazil’s Folha de São Paulo is the new king of the erroneously-reporting-that–Queen Elizabeth–is-dead beat. (It blamed a technical error.)

- And on French election night, the radio station France Inter was pirated in part of Paris.

ICYMI: When it comes to how journalists use it, there’s no such thing as ‘Twitter’

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.