Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On Friday night, Donald Trump did something that he has long liked to do: make news on a Friday night. In a cascade of posts on Truth Social, Trump announced nine appointments to significant roles in his incoming administration, all in the space of an hour or so. (The timing was a full-circle moment for one of those tapped: Sebastian Gorka, who will be a deputy assistant to the president and senior director for counterterrorism, was ousted from Trump’s first administration on a Friday night.) CNN’s Alayna Treene reported that Trump was keen to announce the appointments ahead of the Thanksgiving holiday to ensure that they got news coverage. Not that those making the coverage sounded thrilled about the timing. Politico’s Playbook newsletter noted that Trump had “ruined happy hour for all the reporters who suddenly had to freshen their pre-writes.” “It’s going to be an exhausting four years,” Peter Baker, the chief White House correspondent at the New York Times, wrote on X. “No sleep or rest.”

If this “Friday night news dump” felt like the return of a forgotten cliché from Trump’s first term, it reinforced the return of another that was already in the air: the idea that Trump is putting together a team “made for TV.” Of the selections Trump announced on Friday, two—Janette Nesheiwat, his pick for surgeon general, and Marty Makary, his choice to lead the Food and Drug Administration—were recently contributors on Fox; Gorka was once a Fox contributor himself, and has more recently been a host on the Salem Radio Network and on Newsmax. According to Matt Gertz, of the liberal watchdog group Media Matters for America, the trio brought the number of former Fox hosts or contributors tapped by Trump to nine—the other six being Sean Duffy (transportation), Tulsi Gabbard (director of national intelligence), Pete Hegseth (defense), Tom Homan (“border czar”), Mike Huckabee (ambassador to Israel), and Michael Waltz (national security adviser)—nearly half as many Fox-affiliated picks as Trump managed in his entire first term. Matt Gaetz (not Gertz), Trump’s initial pick for attorney general, is himself a TV fixture who reportedly once considered quitting Congress to join Newsmax; Pam Bondi, nominated to the same post after Gaetz withdrew, has been a Fox regular, if never a paid pundit. And Dr. Oz is Dr. Oz.

In this newsletter last week, my colleague Josh Hersh wrote about this emerging trend, calling it a reminder “of just how much Trump—despite his highly touted campaign dalliances with the world of bro podcasts and social media—is still largely a media traditionalist,” and of how big a story his obsessive viewership of Fox was during his first term. (Who remembers “executive time”?) Hersh focused most of all on Hegseth, until now a host on Fox & Friends, asking former officers who have transitioned into television whether his experience in the latter world might translate into leading a department with a near trillion-dollar budget. (“Being a guy that talks about things in a media environment doesn’t mean you really know about those things,” Mark Hertling, a retired lieutenant general turned CNN analyst, said.)

Now that Trump has finished nominating picks for his cabinet (and most other senior roles), and done so in double-quick time, the relationship between him, them, and TV offers insights into several other key questions about his incoming administration. One has to do with what Trump might actually want his cabinet to do. Others are more concerned with the relevance of TV—and, within and adjacent to that universe, traditional journalism—at a moment when it is being sharply questioned, as well as Trump’s likely second-term relationship with the press. On that score, the return of the “Friday night news dump” might be revealing, too.

As the New York Times columnist Ross Douthat noted over the weekend, Trump’s appointments can be viewed through various lenses. One is the idea that he has, in essence, assembled a European-style coalition government, rewarding nontraditional members of the Republican coalition—Gabbard, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—for their campaign support; another holds that he has tapped harsh critics of government agencies to lead them because he wants to stir conflict and chaos. Borrowing from the conservative journalist Ben Domenech, Douthat noted that Trump can also be seen as compiling, if not a Team of Rivals, then a “Team of Podcasters,” naming picks for their communications skills over their political views or administrative experience. Others seem to agree with this theory: on MSNBC last week, Stephanie Ruhle noted that for all the criticism of Trump’s picks as unqualified, what he’s actually looking for is “spokespeople.” Trump, Ruhle suggested, could in that sense be a reverse Joe Biden, whose team oversaw a substantial policy agenda but struggled to message it.

Personally, I don’t see these three theories as mutually exclusive—and whatever you think of the first two, the third certainly seems to be true. (Trump’s transition “war room” reportedly has big screens on which his advisers have played clips of his potential picks; Trump himself has explicitly praised the TV chops of some of his hires in his announcement posts.) And if (as I wrote on Friday) recent reports of the mainstream media’s irrelevance have been exaggerated (despite the very real challenges posed by this age of fragmented audience attention), then its ongoing relevance to the soon-to-be most powerful man in the country would seem to underscore the point. Whether Fox constitutes part of the mainstream media is a complicated question (as CJR’s Savannah Jacobson explored expertly back in 2021); however you define the term, the Seb Gorkas of the world are not a part of it. Yet Trump also values his surrogates going on major networks that he perceives as hostile and sparring with interviewers. (I noted in August that this was likely a key reason why he picked J.D. Vance as his running mate, and Trump seemed to confirm as much on election night.) As I’ve put it before, of all the TVs things are made for, Trump’s has always been the most important.

If Trump’s personnel picks have often lived by TV, we’ve seen them die by it, too. (During his first term, his national security adviser John Bolton was reportedly ousted after he refused to go on TV and defend Trump stances that he didn’t agree with, setting in motion a TV-mediated dispute as to whether he’d been fired or quit. Since then, Bolton has often been on TV slamming Trump stances that he doesn’t agree with; on Friday night, he appeared on CNN and described Gorka as a “con man.”) Last week, Gaetz withdrew his nomination for attorney general less than an hour after CNN contacted him for comment on a previously unreported sexual encounter that he is alleged to have had with a seventeen-year-old. Around the same time, a source told the Wall Street Journal that Hegseth—who has himself been accused of sexual assault and is the subject of reams of press coverage about it—could likewise lose Trump’s confidence “if this continues to be a drumbeat and the press coverage continues to be bad, particularly on TV.” (Both Gaetz and Hegseth have denied any sexual misconduct.)

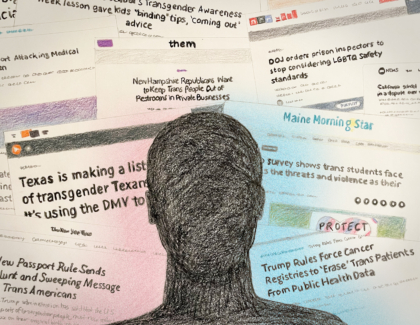

In many ways, the current media environment is very different now than during Trump’s first term: if it’s a misstatement to say that we weren’t already in the aforementioned age of fragmentation back then, we’re deeper into it now; as CJR has reported in depth, journalists credibly face much sharper threats under Trump 2.0 than the mostly rhetorical fusillade they endured last time around. In some respects, though, Trump’s “made for TV” cabinet, and the media discourse around it, suggest that familiar dynamics from his first term are repeating themselves, at least when it comes to Trump’s personal relationship with the press. For starters, we’re likely to see Trump bash members of the media—including, if his pre-election rhetoric is any guide, at Fox—while variously taking cues from them and obsessing over what they have to say. Despite his campaign’s savvy use of nontraditional outlets, Trump is “an almost eighty-year-old man who does care about legacy media and headlines he sees and cable coverage,” the Times Trump-whisperer Maggie Haberman said after he was reelected. “We’ll see how he reacts to it as he goes in because that’s what happened last time.”

The mainstream press, for its part, will likely continue to use TV as a lens to understand Trump and his behavior; indeed, we’re already doing it around his appointments. Those remind us that there’s merit to such framing—and Trump’s first term brought much excellent, sophisticated coverage of how TV as a cultural medium shaped Trump and vice versa. Too often, though, the “made for TV” cliché became shorthand for trivializing Trump’s actions or obsessing over optics or showmanship—or was invoked derisively, to quickly accuse Trump and his team of a lack of substance. (It’s worth noting here that there is nothing inherently unserious about having a background in TV. Indeed, not all Trump’s recent picks from TV are alike: some made their names in the medium while others became pundits only after careers in public service, a common path across the political spectrum.) As I wrote in 2021, the biggest problem betrayed by the “made for TV” cliché was the media’s lesser ability to focus on Trump stories that lacked stimulating visuals. Now as then, what matters most is what he and his team stand for and are doing off-screen, much more so than their prowess on it.

By contrast, the “Friday night news dump” cliché was more a curiosity than deeply telling of any coverage pathologies during Trump’s first term. But it was—and might now be again—itself suggestive of how Trump sees the press and the attention economy, and the contradictions within this view. Trump, of course, did not invent the Friday night news dump; the principal idea behind it—of releasing potentially embarrassing stories when journalists are most likely to be off the clock—is a time-honored one. Last Friday, Playbook suggested that “the volume and timing” of Trump’s personnel announcements “had the immediate effect of diffusing the scrutiny that might have been trained on any individual nominee.” This conclusion wasn’t without complications. Trump has announced his most controversial picks in normal working hours. And as Treene reported, he appeared to want the latest batch to get coverage. (Trump has been known to time big announcements, like the killing of the leader of ISIS, to get maximum exposure on the Sunday shows.)

Still, Trump has used Friday nights to do controversial things in the past: in 2017, the news that Gorka had been ousted was coupled with a pardon for Sheriff Joe Arpaio; in 2020, he fired several inspectors general and commuted his ally Roger Stone’s prison sentence on various Fridays. And either way, Trump often still seems to think in terms of an analog journalistic timetable—further evidence, perhaps, of his old-school media instincts in an age when the twenty-four-hour news cycle has otherwise made the Friday night news dump something of an anachronism. Likewise, his penchant for them could be seen as one small example of his friction with old-school journalists. Perhaps, as at least one observer suggested the last time he was in office, ruining reporters’ happy hours is the point.

Other notable stories:

- The Washington Post’s Elahe Izadi spoke with people distressed by Trump’s victory who consumed a lot of news in the run-up to the election but have since decided to tune it out. It’s not yet clear how widespread such behavior might be, but this moment “feels very different from 2016,” when, in the wake of Trump’s victory, “each new, seemingly unbelievable development generated breathless coverage, and enormous ratings,” Izadi writes. Such behavior also “runs counter to how people tend to react to something they consider a ‘tragedy,’” one expert told Izadi: “When an event happens that distresses people, those people consume more information about it”—a “pull to bad news” that is so profound, people go along with it even if it is bad for them. The difference this time could be that news consumers lack control over Trump’s actions.

- Recently, we’ve noted in this newsletter that various government ministries in Israel had cut ties with the left-leaning newspaper Haaretz; officials said that they were responding to controversial remarks that the paper’s publisher made about Palestinian “freedom fighters,” but Haaretz accused them of seeking a pretense to smear the paper. Now Shlomo Karhi, Israel’s communications minister, has said that the government as a whole has approved a full boycott of Haaretz, including the withdrawal of all state-funded advertising from its pages. Haaretz responded by accusing Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, of “trying to silence a critical, independent newspaper,” and pledged not to “morph into a government pamphlet.”

- In Thursday’s newsletter, Sarah Grevy Gotfredsen noted that major news organizations in several countries—including The Guardian in the UK and La Vanguardia in Spain—had decided to quit X in the wake of the US election, citing the toxic discourse on the platform and the status of its owner, Elon Musk, as a top Trump ally. Ouest-France and Sud Ouest, two regional media groups in France, have now made the same decision. Le Monde’s Brice Laemle asked other French news organizations whether they would follow suit; of those that responded, some pledged to stay and make their voices heard on X, while others are still deliberating.

- The Post’s Manuel Roig-Franzia profiled Alsu Kurmasheva, one of the US journalists who was imprisoned in Russia before being freed in a prisoner swap earlier this year. In other news about Russia and journalism, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists is out with “the Caspian Cabals,” an investigation revealing how Western oil companies played into Vladimir Putin’s hands over a pipeline project. And Bloomberg’s Jason Leopold finally obtained a declassified US government report about the targeted assassinations of Putin’s enemies, after more than eight years of freedom-of-information efforts to pry the document loose.

- And Jeffrey A. Roberts, the executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, wrote about a brief that the group has submitted to the state’s supreme court challenging a ruling in which an appeals court sided with the Aurora Sentinel newspaper in an open meetings lawsuit that it brought against the city—but declined to award attorney fees to the paper because only “citizens” are eligible to claim those in such cases, and a newspaper does not meet the Merriam-Webster definition of that term. The CFOIC argues that the Sentinel should be eligible for fees.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.