Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

A week ago, we learned that Prince Harry and other celebrity plaintiffs in a phone-hacking lawsuit against Rupert Murdoch’s UK media business had alleged in court that Will Lewis, a Murdoch executive who was tapped to clean up the phone-hacking scandal in the early 2010s, instead “fabricated a fake security threat” to justify deleting millions of emails that, the plaintiffs say, contained important evidence related to the scandal. The details date to 2011, when Lewis told police that the company deleted the emails because executives had heard that Gordon Brown—a former British prime minister who believes that his phone, too, was hacked—was conspiring to steal them. Last week, Brown, who has strenuously denied any involvement in such a plot, revealed that he recently reported concerns about the email-deletion to police in London, and that they have since opened a preliminary inquiry into the episode.

The story remains murky in many respects: Lewis is not a target of the phone-hacking lawsuit brought by Harry and others, nor is he yet under criminal investigation in the email-deletion inquiry; he has previously denied claims that he was complicit in any alleged cover-up of phone-hacking at Murdoch’s UK business, which has itself claimed that it thought the allegations about the Brown-theft plot were genuine and that, in any case, they weren’t the reason for the email deletion, despite what Lewis is reported to have told police at the time. (Don’t worry—I’m confused, too.) And the reverberations of the latest Lewis news were felt most keenly not in the UK, where it all transpired, but across the Atlantic: Lewis is now the publisher of the Washington Post, where he has come under pressure following a slew of unflattering headlines about his past; those appeared to have abated, but last week’s news reignited them. In an op-ed for The Guardian last week, Brown drew attention to the Post’s motto, “Democracy dies in darkness,” asking, “What if the publisher himself is a master of the dark arts?” In an interview, he suggested to NPR’s David Folkenflik that the Post should reconsider Lewis’s appointment.

Still, the latest Lewis story resonated in a British-media context, too. Indeed, it formed part of a significant broader week of news about the British media business and its social media counterpart—one that illuminated the long tail of the hacking scandal even outside of the Lewis controversy (albeit, perhaps, less directly), while echoing the early-2010s political climate in which that scandal played out, with talk of troubling allegations involving the BBC and child sexual abuse, and a series of riots. The new stories on these fronts are very different, both from each other and from their historical analogues. But assessed together, they show, as I’ve written before in this newsletter, how British media moments can at least rhyme with those of the past, forming part of a longer history of continuity and change. They show, too, the enduring relevance of the traditional news media—and various sharp questions that it faces.

Around the time that news of the latest Lewis controversy was breaking, police in London confirmed that Huw Edwards, a leading former news anchor on the BBC (whom the New York Times once likened to Walter Cronkite in stature), had been charged with possessing “indecent images” of children that he had been sent on WhatsApp; on Wednesday, Edwards pleaded guilty. His conviction was a coda to a murky episode that I wrote about a year or so ago, after the right-wing tabloid The Sun reported that an anonymous BBC anchor had solicited “sordid images” from someone who was too young to legally consent to sending them. Edwards eventually identified himself as the subject of the story, while checking himself into a hospital following a “serious” mental health episode. The BBC faced questions as to what it knew and when—but so did The Sun, after a lawyer for the alleged victim in its story (whose parents were the ones who spoke to the paper) dismissed it as “rubbish” and denied that anything untoward had happened.

In the end, Edwards was convicted on charges unrelated to The Sun’s reporting—but in the wake of the news, the alleged victim from The Sun’s story told a different tabloid, the Mirror, that he now feels Edwards took advantage of him and that he regrets trying to “protect” Edwards at the time. Taken as a whole, the episode echoed a massive scandal that hit the BBC starting in 2012, when historical child sex abuse claims were leveled at several of its employees, most notoriously Jimmy Savile, a BBC entertainment star (who died in 2011). There’s no suggestion that the BBC knew anything about the allegations that led to Edwards’s conviction until he was arrested late last year, but various observers have suggested that the broadcaster has questions to answer (not least since it only parted ways with Edwards in April of this year).

The story has also reignited a debate about Britain’s strict privacy laws that is, in many ways, inseparable from the hacking scandal and its fallout. In its story last year, The Sun reportedly did not name Edwards due to these laws (at least in part), and yet it still faced some criticism for setting in motion a chain of events that ended up breaching Edwards’s privacy, without it being totally clear, at the time, that this was justified in the public interest. Now the paper is claiming vindication (even though Edwards was convicted on separate charges), taking aim at perceived “tabloid-haters” including a campaign group that was formed in response to the hacking scandal. “We’ll leave them to examine their own consciences, and now ridiculous-looking Twitter feeds,” the paper wrote.

In part, the role of social media was at issue in the debate over privacy and the Edwards story, with some critics of The Sun’s reporting suggesting at the time that while it withheld his identity, it invited online speculators to fill the vacuum. (Either way, this very much happened.) As last week progressed, the role of social media was central to another, very different story that initially battled the Edwards conviction for airtime (including on the BBC) but has since come to dominate the news cycle: a series of shocking racist riots in English towns and cities that led, yesterday, to attacks on two hotels that were reported to be housing asylum seekers—and that don’t appear to be done yet. This story, too, echoes events from 2011, when a series of riots were catalyzed by the police shooting of a Black man in London.

The spark for the present, far-right riots was a mass stabbing in the northern town of Southport, where an assailant killed three young girls at a Taylor Swift–themed dance class and injured ten other people. Many observers have pinned the spread of the riots since then on social media (as also happened, in a different context, in 2011): in the aftermath of the stabbing, a false claim that the suspect was an asylum seeker from Syria went viral online, supercharged by a variety of high-profile far-right accounts. (In fact, the alleged attacker was born in Wales.) Questions have since been raised about the role of a fake-news site with possible (though unproven) ties to Russia, as well as social media companies’ role in policing their platforms; in recent days, Keir Starmer, Britain’s new prime minister (incidentally, the first Labour Party occupant of the office since Gordon Brown), has repeatedly warned them of their responsibility to stop the whipping-up of violence. (Elon Musk—the owner of X, which last year reinstated the account of a notorious British far-right activist—described Starmer’s remarks as “insane”; Musk has since himself said, in response to a far-right talking point about the riots, that “civil war is inevitable.”)

The perception that social media has stoked the riots has led to calls for government regulation; Carole Cadwalladr, a British journalist who has long covered scandals involving Big Tech, described Musk as “a feckless billionaire whose algorithms pose an imminent threat to life” and argued that this should be a “Dunblane moment,” a reference to the aftermath of a school shooting in Scotland in 1996 that led to strict restrictions on firearms in the UK. Others, though, have suggested that social media is not the principal culprit, arguing, as one academic put it, that “newspapers and word of mouth have spread mass hatred leading to comparable outcomes in the past,” and suggesting that, in this case, toxic political rhetoric about immigrants and ethnic minorities is more to blame—rhetoric, many pointed out, that has found loud echo in the right-wing press.

Critics have also taken Britain’s traditional media to task for a perceived double standard in coverage of this unrest compared with that of 2011, calling out, for example, recent stories that have spoken of “protests” rather than “riots.” The traditional press has also been a target of the rioters, facing threats both online and physically, in trying to cover events on the ground. (At least one placard bashed the BBC—citing its handling of the Jimmy Savile scandal.) The various media issues the riots have raised are, in many respects, different from those of the Edwards and Lewis stories, which have more to do, respectively, with news organizations’ safeguarding responsibilities, the contested limits of privacy, and illegal reporting methods. But there are links between these debates, too. And the stories of the past week all show that the traditional media, how it covers important stories, and its freedom to do so remain vital topics for discussion—just as they were eleven, twelve, or thirteen years ago, in the UK as elsewhere—even if the role of social media is driving the more voluble reckoning for the moment.

The riots have also, to some extent, brought into focus the persistent lack of resources to fund British journalism, particularly at the local level, a problem that I’ve also written about in this newsletter, in direct connection with the idea of media moments in the present echoing those of the past; Gareth Davies, the editor of an investigative journalism network in the UK, pointed out that as rioters start to be dragged through the legal system, many will face justice in a court where no reporter is present. As Gordon Brown noted in his op-ed about Will Lewis last week, one narrative that has surrounded the latter’s arrival at the Post is that he was hired to import a “nimble ‘no-holds-barred’ British journalism”—one adept at stretching tight budgets—as an antidote to the paper’s recent financial struggles, and that this has been a key driver of the resistance to his appointment. The real story of his hire, Brown argued, is not about a “disrupter and an entrenched resistance to change,” but “ethics and the lack of them.”

Other notable stories:

- On Friday, I wrote in this newsletter about the massive prisoner swap that led Russia to free the American journalists Evan Gershkovich and Alsu Kurmasheva. Since then, the story has continued to reverberate in the news cycle. After Gershkovich’s paper, the Wall Street Journal, published a detailed behind-the-scenes account of how the swap came together, the New York Times published an account of its own. The AP profiled a journalist who was swapped in the opposite direction: Pablo González, a contributor to the Spanish news agency EFE and (briefly) Voice of America who was arrested in Poland in 2022 on suspicion of being a Russian asset. And New York’s Charlotte Klein reports on fury, among journalists and US officials, with Bloomberg, which broke an embargo to report on the swap while US prisoners were still on a Russian plane.

- Last night, Max Tani noted, in Semafor’s media newsletter, that the Journal has been widely praised for its prudence in its coverage of the Gershkovich case—but that “some critics and staff have questioned whether the paper should have demonstrated similar restraint” around a different story involving a foreign conflict: a January report claiming, based on Israeli intelligence, that 10 percent of Gaza-based staffers at the Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, a UN agency, had ties to militant groups. The US and other countries froze funding for UNRWA following this and other stories—but Tani reports that months later, the paper still doesn’t know if the claim is true. (The Journal said in a statement that it stands by its reporting on the claim.)

- Politico’s Michael Schaffer explored a recent federal indictment alleging that Sue Mi Terry, a former CIA analyst and policy expert, acted as an unregistered agent of the South Korean government—and how the charges have rebounded onto her husband, Max Boot, a columnist at the Post who has cowritten articles with Terry and urged tough enforcement of foreign-agent laws, not least in the context of the Trump-Russia story. (Terry has denied the charges. Boot has not been accused of wrongdoing; the Post said that he will remain a contributor.) If the Terry allegations haven’t caused a huge splash in DC, Schaffer argues, “it’s because the Beltway is inured to some pretty lousy stuff.”

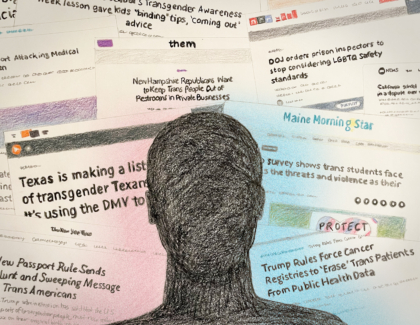

- In recent days, anti-trans activists and others have spread misinformation about Imane Khelif, a female Algerian boxer at the Olympics who has been misidentified as transgender or a man since an opponent withdrew from a fight last week, citing the strength of Khelif’s punches. Amid the furor, the Boston Globe ran a print headline that itself incorrectly described Khelif as transgender, then ran a correction that failed to note that she was born a woman. The Globe acknowledged “the magnitude of this mistake,” and apologized to both Khelif and the AP writer whose story it incorrectly headlined.

- And—in a bizarre video with Roseanne Barr that he posted over the weekend—Robert F. Kennedy Jr. addressed a report (which appears in The New Yorker today) that he once placed a bear carcass in Central Park and made it look like the animal had been hit by a bicycle. The Times covered the dead bear at the time—in an article written by Tatiana Schlossberg, a reporter at the paper and daughter of Kennedy’s cousin. She said yesterday that when she wrote the story, she “had no idea who was responsible.”

ICYMI: The moral trade-offs NABJ made in inviting Donald Trump to the stage in Chicago

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.