Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Jay Caspian Kang collects basketball sneakers. He surfs. He plays poker and says he once lost $9,000 to a stripper wearing heart-shaped sunglasses in Las Vegas. He picked his own middle name at the age of 8 after reading The Chronicles of Narnia. He won a corned-beef-eating contest in college, where he estimates his GPA was 1.9. He survived cancer and has a scar on the front of his neck to prove it.

In seven years as a writer, blogger, and journalist, Kang, 37, has produced a genre-crossing and unpredictable body of work including memorable bylines with titles ranging from prestige to obscure. His writing on sports, pop culture, gambling, civil rights, and what it means to be Asian-American has attracted praise for style and thoughtful analysis on race. He’s written about the superiority of a particular baby stroller, and on why he thinks the term Asian-American is “mostly meaningless.” His features often include deep reflections on his identity and his past, and humorous references to his quirky range of interests. Last year, he added broadcast to his résumé, joining HBO’s Vice News Tonight to report stories about civil rights and injustices involving race.

ICYMI: Former NYTimes journalists are ticked off by new Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks movie

Kang is smooth-faced, sleepy-eyed, and comes across as a little restless: frequently checking his phone, running his hands through his hair, or looking like he’s worried. In conversation, he can go from laughing about pop culture to deep, intellectual arguments, filled with references to great authors and complicated world events.

In June, shortly after the first of several interviews with CJR, Kang published a sports column about why picking a team for his daughter to root for, as the son of Korean immigrants, meant examining everything he knew about a sense of origin and belonging. “I didn’t really set out to write about race at all,” he tells me. “But then by the middle of it I was just like, this has to be an element. And then it sort of takes over.” Then in early August, The New York Times Magazine published “Not Without My Brothers,” Kang’s feature on the death of Chinese-American college freshman Michael Deng and the culture of Asian-American fraternities. Readers hailed the cover story, which Kang reported for a year and a half, as an apt reflection of the complicated feelings Asian-Americans, especially young Asian-American males, have about their place in the United States. Kang’s work places him in a pantheon of Asian-American writers—including Jeff Chang, Wesley Yang, Mary H.K. Choi, Frank Shyong of the Los Angeles Times, and Hua Hsu at The New Yorker—who have tackled identity and developed a following by writing about their own experiences.

“Whenever I tweet something he’s written on the subject [of Asian-Americans], immediately 100 Asians will fill my mentions,” says Mina Kimes, a senior reporter at ESPN The Magazine and a close friend of Kang’s who first bonded with him over their mutual love of American Idol. “There’s such a craving for that kind of writing addressing those issues, and it’s just not really been filled.”

ICYMI: A recent op-ed made a very important point about the word “collusion”

Kang’s writing demonstrates a gift for observation, plus a solid dose of amusement about the situation around him and his place in the midst of it all. In “How Golf Makes You Confront Your Mortality” for the Times, he explained his unusual tolerance for physical, repetitive pain: “If there were a sport in which the athlete moved a stack of cinder blocks across a field while listening to a podcast, I might have been able to ride the pine for a minor-league team.”

Playing golf, he writes, is like getting “kicked in the groin if your groin were in your brain.” Kang attempts to quell his deep sense of disappointment with his swing performance with “bastardized sutras” he learned while studying Buddhist meditation:

Please don’t overswing, you’re strong enough. The tiny Korean women on the L.P.G.A. tour can hit the ball 250 yards.

There is nothing to attain.

You’re definitely overswinging. Good Christ. There’s nothing that can be done.

All form is emptiness.

Ball right again. Guy next to me definitely laughing. I am a disgrace to the Korean people.

Kang’s assessment of his performance in other sports is just as blistering: “My swimming stroke, which once wasn’t half bad, now looks like what might happen if you stapled a pair of flapping hands onto a filing cabinet and threw it into the ocean.”

In “Writing Waves,” an essay about his years of daily surfing as much as it is a review of William Finnegan’s book Barbarian Days, Kang wrote, “I concluded that writing about surfing was impossible because surfing elicited happiness, and it is impossible to write about happiness.”

Kang as an opinionated, high-minded “bro” with a restless intelligence, finely developed intuition about the world, a strong, argumentative, comedic way of putting things, and a love for short, compact, scrubbed sentences.

New York Times Magazine story editor Sasha Weiss describes Kang as an opinionated, high-minded “bro” with a restless intelligence, finely developed intuition about the world, a strong, argumentative, comedic way of putting things, and a love for short, compact, scrubbed sentences. “He likes clarity, he doesn’t like pretension; he’s not a fancy writer. But that’s something you have to work at to sound as good as it does when he does it. He wants readers to understand what he’s saying.”

Kang is conscious of not just differentiating himself as a writer but also avoiding structures and points of view that have become cliché in sportswriting, says Kimes. “Not only is he a writer with a very unique style, he’s also looking at this athlete or subject in a way that is not typical,” she says. “It’s hard in sportswriting to be different. The same stories do repeat themselves over time—there’s the underdog, the competitors, and the champion—it’s very hard to be original. I think everything he does is so completely original that it really stands out.”

Weiss says it helps that Kang is a “ball of contradictions” interested in nonconformity, protest, social justice, and resistance of all kinds.

“He’s constantly telling you what he thinks, and what he thinks is constantly changing. I think he would hate to be known for only writing one kind of piece,” she says. “And I think he resists whatever the dominant narrative is. It’s very hard to pin him down and predict what he would say.”

Jay Caspian Kang automatically deletes his tweets after a week or so. So we grabbed some screenshots to give you a taste for his quirky feed.

***

Born in Seoul, South Korea, on New Year’s Eve, Kang began writing at a very young age, but it would be hard to find glimmers of his narrative talents or his literary ambitions in the content of his childhood journals. Kang says the task, commanded by his mother to ensure chore completion between the ages of 5 and 14, led to “exhaustive, daily recordings of the unessential”: what he ate for dinner or why he didn’t like the hot summers as a child in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His first college writing course, at Bowdoin, wasn’t until his senior year, but he quickly decided he wanted to be a novelist, opting to attend Columbia for his MFA immediately after finishing his undergrad degree at City College. “I just wanted to make enough money to live and not have a job and do readings,” he tells CJR.

After graduating from Columbia in 2005, Kang spent a few busy years in San Francisco and Los Angeles—teaching creative writing and world history; playing poker for more than 40 hours a week at the Commerce Casino; and penning two novels—all while surfing in the morning and playing the video game Modern Warfare 2 for a few hours around dinnertime. In January 2010, he found another pastime, which paid nothing but would launch the trajectory of his career in journalism. He began blogging for a literary basketball blog called FreeDarko, named after the Serbian player Darko Milicic. Kang’s first post, “The Lives of Others,” was about Chinese-American basketball player Jeremy Lin, Chinese-American rapper Jin the MC, and how the two men “offered an alternative interpretation of what it meant to be an Asian-American.”

Those of us trapped within the metanarrative have been conditioned our entire lives to imagine White. Like Jin before him, what Jeremy Lin represents is a re-conception of our bodies, a visible measure of how the emasculated Asian-American body might measure up to the mythic legion of Big Black supermen. Within that singularly American calculus, it’s not about basketball at all. It’s about our fucked up anthropology.

Nathaniel Friedman, who edited the site, says Kang stood out right away for how much he was able to pack into sentences while staying measured and focused. “Jay’s emails were smart, funny, inventive, and fairly bonkers at times. I was also struck by just how mature his writing was,” Friedman says. “I definitely felt like I was reading someone who could be both fine-tuned and searing in ways that just require an incredible amount of talent and discipline.”

“We didn’t pay, so I don’t know why he wanted to write for it,” Friedman adds.

TRENDING: New York Times makes important statement about mass shootings with a series of clocks

Later that year, Kang’s mother noticed a large, swollen lump on the front of his neck, which turned out to be thyroid cancer. He underwent two surgeries and a round of chemotherapy and will need a daily dose of thyroid hormone for the rest of his life. But the “relatively easy” process, Kang says, makes him feel a little entitled and “a bit of a douchebag.” “Cancer had afforded me a short honeymoon with my childhood,” he later wrote of the experience. “Surviving cancer can cleanse the soul, sure, but once you’re left facing the rest of your life, a patient’s vision can tunnel down to a list of demands.”

Kang’s list focused on a career as a writer. A few stories in particular helped him turn a small but loyal following into a up-and-coming “voice” editors craved to work with. Eight months after his first post for FreeDarko, the blog The Awl published Kang’s “scientific evaluation” of the greatest divas of the last 25 years. It explained—using a series of Microsoft Excel charts and categories judging overall commercial success, vocal strength, and “wearing insane hats”—why Whitney Houston edges out Aretha Franklin for the No. 1 spot. A few weeks later, an online magazine of essays, art, humor, and culture called The Morning News posted “The High is Always the Pain and the Pain is Always the High”—a 5,000-word, seven-chapter, first-person essay on Kang’s gambling addiction he had written five years prior, not long after finishing grad school at the age of 25.

A sample:

I could tell you that during a 36-hour period in July of 2006, I lost $18,000 in Las Vegas. Or I could tell you I once picked through every corner of my car, including the grating underneath the spare tire, for five dollars of spare change so that I could make the minimum bet at a blackjack table (a bet I lost). And my interest in divulging these details would not be to instruct or to edify, or even to elicit empathy from fellow addicts. My interest would be to rip open my suffering heart and show you its beautiful beating, and in this way, I might think of myself as having been more alive than you, my hopefully horrified reader, were at a similar age and time.

Both pieces would be noticed by prominent editors and mark a turning point in Kang’s career.

He was with his girlfriend, Casey, on a business trip in Angkor Wat, Cambodia, in early 2011 when he found out his agent had sold his crime novel about the murder of a young Korean-American man’s next-door neighbor. The same day, The New York Times Magazine wanted Kang to write 3,500 words about poker for $2 a word. (For his earlier piece on his gambling addiction, for The Morning News, Kang was paid $50, a rate of one cent per word.)

The sports journalist Bill Simmons, then in the process of building his Grantland sports and pop-culture site, had also noticed Kang’s piece in The Awl. “When I was creating Grantland, a big part of the mission was trying to write about pop culture the way everyone wrote about sports—more fun, more creative, more big picture, more argumentative, just different,” Simmons writes in an email to CJR. “That was like the quintessential example of how I wanted us to be thinking. Then I found out Jay loved basketball and baseball, and we were off.” Shortly thereafter, over lunch, Simmons offered him a founding position at Grantland.

All of this, from the novel to the Times to Grantland, happened in less than two weeks.

“I felt very crazy because I had just had cancer and I was really fucked up, not physically but in the head,” Kang says of the time. “I had no money. I just had this surgery, and now I have to worry about my health all the time, and I just met this girl.”

At Grantland, Kang was officially an editor but also often wrote long features, many of them about race and culture. He mixed long descriptions and intimate details about his life into reflections on the greater cultural significance of sports figures like Japanese Major League Baseball all-star Ichiro Suzuki and Lin. The LA office was a small, tight-knit group of eight. “Jay was a big part of it,” Simmons says. “He was very good at spotting talent on top of everything else.”

“It was like summer camp,” says Rafe Bartholomew, a friend of Kang’s, FreeDarko contributor, and a fellow Grantland editor.

ICYMI: Grantland Rises

Kang still considers his profile on boxing promoter Don King, which landed in the 2014 edition of Best American Sports Writing, one of the best things he’s written. “This guy rose to the top of a profession that used to be controlled by the mafia, that was extremely racist and regularly ripped off all the black players,” Kang explains. “Don King genuinely thinks of himself as a civil rights hero.”

“It’s really difficult to write a profile about someone who’s all good or all bad,” he adds, later noting, “I imagine I am a bad profile subject, like 99 percent of journalists.”

While he was editing and writing profiles for Grantland, Kang’s debut novel, The Dead Do Not Improve, was published by an imprint of Penguin Random House in 2012. The story centered around Philip Kim, a young, disgruntled Korean-American man working at a social media site who gets caught up in the details of the murder of his elderly next-door neighbor. It was inspired by a moment Kang had in 2007, after he learned the shooter behind the Virginia Tech massacre was Asian, and instinctively knew the person was Korean.

How did he know? Well, as he wrote in the book:

The Chinese aren’t creative enough, the Nips don’t have the balls or the specific brand of Korean crazy, which is really just the same as Irish crazy, because both peoples come from small countries oppressed for hundreds of years by assholes across the way. Both peoples grew up under the eye of the crown or the fucking emperor and learned to suppress everything, especially anger, until they no longer could distinguish what was what, and could walk around angry without recognizing anger as anger. And the prescription for whatever else was drinking.

The book was panned by Publisher’s Weekly, whose review called Kang’s voice “at once glib and vitriolic” but also acknowledged his “gift for snide zingers” as well as “un-PC digressions on race and ‘Koreanness.’” Kirkus Review was more positive, calling the structure of the “Pynchon-esque” tale “loose to the point of near-collapse” but that it also contained “serious musing on gentrification and racism (particularly toward Asians),” and “surprisingly affecting observations.” Kirkus added, “Smart, funny and eager to fly its freak flag.” The Los Angeles Times called Kang “an author worth watching.”

In April 2014, Kang left Grantland to edit The New Yorker’s science-and-technology blog Elements. For Kang, the most enjoyable aspects of his positions at Grantland and then at The New Yorker were finding young writers, figuring out story ideas during meetings, and collaborating with other editors. “I would always think of, ‘Who is this person as a writer, and how do we get them to the point they’re the best version of themselves?’”

Jay Caspian Kang hard at work with his writing assistant, his dog Chito, a Chihuahua mix. Courtesy photo.

ICYMI: The most annoying thing an editor can do

***

Kang didn’t actually like editing. He was surprised how many people asked him why he left the Condé Nast title after only six months. “I thought it would get my foot in the door of writing for the magazine,” he says. “But I found out very quickly almost everyone working there wants to write for the magazine, and those people are immensely talented.”

“I just think I wasn’t very good at [editing], especially at the pace I was doing it.”

After leaving The New Yorker in November 2014, Kang was feeling burned out from writing and wasn’t happy with how much money he was making. “At the time, it seemed like being a magazine writer, journalist, and book writer forever might be impossible financially,” he says. So Kang signed up to be a contributor for The New York Times Magazine on a freelance basis and worked for the advertising firm Wieden+Kennedy in Portland, Oregon. “They wanted to get in on making branded content that didn’t feel like branded content,” says Kang, whose foray into advertising lasted only six months. Part of his new job was trying to convince brands to sponsor platforms that would have their own personality and readership that were invested with genuine interest in a way that wasn’t “pay-to-play.” One of these was On She Goes, a digital travel site for women of color.

Kang says he didn’t feel compromised doing advertising work while still writing for the Times Magazine. Even though his paycheck in advertising was much higher than anything he made working full-time in journalism, the career and location change couldn’t be permanent: Kang’s now-wife Casey was pregnant, and she didn’t want to move away from their home in Brooklyn to join him in Portland.

And so last July, Kang returned to New York and a full-time career in journalism to join Vice News Tonight as a civil rights correspondent. His work so far includes multiple dispatches on the protests at Standing Rock, the deportation of Korean adoptee Adam Crapster, the controversial theory ancient marble statues aren’t actually supposed to be white, and an early report on high school students adopting the national anthem protests against police brutality, a segment that was nominated for a Emmy award.

Kang has always loved documentaries and was excited to learn how to shoot, edit, and get proper sound at his new job with Vice. And while Kang is not the company’s first on-camera host to come from a non-broadcast background, he says the learning curve was still high. “There’s more pressure [than writing] because your face is there,” he says. “You can’t just show up and be yourself.”

“I still sometimes think of myself as a novelist,” he says, “even though I haven’t written a word of fiction since the novel came out six years ago.”

For Kang’s Vice segments, he narrates, does interviews and sometimes writes long, online features for additional context. His on-air look is pretty simple and not much different than his non-work look: T-shirts, button-downs with the sleeves rolled up, black casual pants, and sneakers. Sometimes Kang will put on an ill-fitting formal jacket while interviewing a government official.

In his HBO profile photo, Kang wears a bright blue T-shirt and sports a close-cropped haircut with a little bit of gray. He somberly looks straight at the camera with a sense of sadness and exhaustion in his eyes.

***

A significant majority of Kang’s columns, television segments, and magazine features have a central focus on the role of race in culture, like his 2014 profile of food celebrity Roy Choi in California Sunday Magazine.

“Koreans drink more liquor than any other nationality on Earth, and Choi’s resentments toward the hierarchies and constraints of Korean culture are so familiar, they almost read rote,” Kang wrote. “Every Korean man I know who’s under 40 listens exclusively to rap and identifies, at least in part, with black and Mexican American culture. Roy Choi, then, is not unique — he is the ggangpae, the street kid, in all our families. The portrayal of him in the press as an anomaly, as someone who doesn’t fit the usual Asian American narrative, actually says less about Choi than it does about how narrow and sclerotic that narrative can be.”

There is part of me that sometimes thinks it’s easier, less of an accomplishment that I write something about race. I don’t think white journalists worry about this.

Kang, believe it or not, worries he might be running out of things to say about race. This is despite his new book deal, announced October 10, for The Loneliest Americans, described by Publisher’s Lunch as “an interrogation and investigation of identity and what it means to become, and to feel, ‘American,’ filtered through [Kang’s] own experiences as Asian-American.” He also admits to CJR that in his head, he has a clear division between his work that’s focused on race, and the work that isn’t. “There is part of me that sometimes thinks it’s easier, less of an accomplishment that I write something about race,” he says. “I don’t think white journalists worry about this.”

Still, Kang knows his background in fiction, his interest in the subject, and his perspective all help elevate his work. “I find that I just write better when I’m writing about something that feels a little bit more personal,” he says. “I don’t think I’ve really mastered the detached third-person part. I think it’s probably not possible for me to write that way, or I would have, and it would have been better for my general marketability.”

“When I pull back a little bit, it becomes really obvious to me that all the ‘obvious’ questions that are out there are influenced by how I see the world,” he adds. “It’s always through the lens of being an immigrant to the country. And it always feels dishonest not to do so.”

Hyper-awareness of his privileges—an upbringing in Chapel Hill and Cambridge, Massachusetts, with well-educated parents and a degree from an Ivy-league university—also guides some of Kang’s writing and reporting, like in the case of the Times piece on Asian-American fraternities. “I don’t know what it was like to grow up in Flushing or Koreatown or very Asian enclaves, and I’m really interested in reporting on it because it’s a personal thing for me,” he says. “How would my life have been different if I had grown up like my cousins did in LA, where every single person you see is Korean, you hear Korean all the time, and your parents don’t really learn English because they don’t have to? And you just live in this immigrant bubble.”

ICYMI: How Pamela Colloff became the best damn writer in Texas

***

A few days before Kang’s one-year anniversary at Vice News Tonight, I asked him what he wished he’d known before he started. “I wish I had gone on a diet immediately and lost weight,” says Kang, who sports the slightly pudgy physique of a new dad. “I wish I had taken acting or elocution lessons. I wish I had any knowledge of what makes a good TV segment. You can’t fake anything. In writing, you can fake a lot and make one gesture seem like a lot. You can’t do that in television.”

Despite the major magazine titles on his résumé, Kang suffers the same self-criticism that plagues the rest of us, and says he doesn’t consider his career that successful thus far. “I haven’t had any scoops that changed policy,” he says. “I haven’t gotten anyone off from prison. Maybe in the world of ‘journalist Twitter’ I’m doing pretty well, but that’s such a fake world. I feel very restless all the time. I can name, like, 20 more successful people that I talk to regularly. I just get this real intense feeling of inferiority, and then it just stews a bit.”

I just get this real intense feeling of inferiority, and then it just stews a bit.

Kang has his detractors. His Times Magazine piece “The Dark Side of American Soccer Culture” was about racist incidents of sports hooliganism. The commissioner of Major League Soccer, Don Garber, called the piece “poorly reported, factually incorrect and irresponsible, with a lack of any research whatsoever.” The National Review said “the phenomena Kang is exposing simply doesn’t exist.” Kang also received criticism when he defended the publishing of “My Family’s Slave,” the personal essay and cover story by Filipino-American journalist and Pulitzer-winner Alex Tizon in The Atlantic about the life of his family’s unpaid domestic servant. Kang praised Tizon’s troubling, yet brutal account of what happened: “It’s a stunningly honest piece about something second-generation immigrants rarely address — the old-world sins of their parents and the frustration, indignation, and distance we feel whenever we encounter the trenchant, ugly things our parents brought with them.”

On the other hand, Greg Howard of The New York Times Magazine and David Remnick of The New Yorker in interviews with CJR pointed to Kang’s feature “Our Demand is Simple, Stop Killing Us” on the Black Lives Matter movement. “He helped make DeRay [Mckesson] a nationwide story,” says Howard in an interview with CJR. “Jay played a small hand in big institutions like The New York Times taking DeRay seriously and young Black people seriously, because Jay took police brutality seriously.”

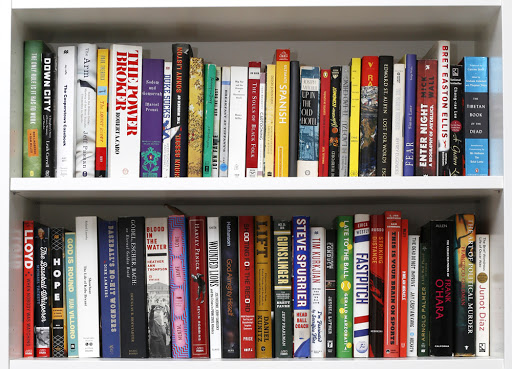

Kang is a voracious reader (“I read a lot of Twitter and a lot of books on my phone,” he says, “mostly old-man books about war history. The last good novel I read was Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs.”) and an intensely competitive person. He’s also constantly analyzing and breaking down what other people are writing, reporting, and producing. “Like every time I have a thought on something, [Jia Tolentino of The New Yorker] is just better.”

Kang has a strong track record for recognizing talent as well as constantly reading new writers of color. “You talk to Jay and he’s rattling off people that I’ve never heard of,” Howard says. “I don’t think Jay reads mostly white people.”

***

Kang’s attention to diverse voices isn’t a recent phenomenon. For years, Kang has been critical of the media industry’s poor efforts around diversity. When it came to Serial, a blockbuster crime podcast that chronicled the cold case of Hae-Min Lee, Kang argues on his blog that journalist and host Sarah Koenig demonstrated white privilege in journalism by stereotyping and whitewashing Lee; Adnan Syed, the man serving a life sentence for the crime; their life experiences; and their two very different immigrant cultures. In “An Open Letter to Fellow Minority Journalists,” Kang lays out how many journalists and writers of color were hired “as part of a cynical push to turn ‘race writing,’ especially race writing about pop culture, into a click factory” and why the results of the 2016 election would likely lead to situations where “editors and publishers will start hiring alt-Tucker Carlsons so they can hear both sides. They will need to clear headcount spots to do this and they will quietly start purging the same writers they hired so enthusiastically — with rousing rounds of Tweet applause — two years ago.”

ICYMI: Why aren’t there more minority journalists?

During his brief time at The New Yorker, Kang regularly met with other non-white staffers in the Condé Nast building to talk about how much the company, and the industry at large, lacked diversity even at the assistant level. Since Kang left the magazine in November 2014, a significant number of minorities have been made full-time staff writers and editors. Remnick acknowledged his magazine has hired and published more people of color to go beyond the “bland, suburban, white” tone it was once known for. “It should reflect the intelligences and experiences of the world,” he said during a lecture at the Columbia Journalism School in May. “And the talents.”

There’s no shortage of Asian-American writers who want to follow in Kang’s footsteps. Joon Lee read Kang’s work for years and decided to go into sports writing in college. After meeting Kang for lunch at a Chinese restaurant in New York, and with his encouragement, Lee scored a break writing about internet celebrity and tech reviewer Marques Brownlee for what would eventually become The Ringer. Now the 22-year-old Lee is a staff reporter at Bleacher Report and B/R Mag.

Kimes, of ESPN, says Kang is someone a lot of younger sportswriters, especially those who are writers of color, look up to. “It’s hilarious to me to think of him in that role because I think of him as young, but that’s where we are this community. We’re younger, and there’s fewer of us.”

The media is so overwhelmingly upper-middle class. Writing about race now has become the racial anxieties of that class of people, and I just find it insanely boring.

Kang may be a role model, but he doesn’t sugarcoat the challenges. At a panel of the Asian American Journalists’ Association national convention in Philadelphia in July, Kang said it’s not a great time to be writing about race because thoughts and presentation have been standardized; assignments are too heavily focused on pop culture; or arguments carry too many caveats. “People are so afraid of being trolled on Twitter,” he said. “Everything reads exactly the same to me.”

“I think I get assigned a lot of stories about race because I’m not white,” he mumbled, to laughter from the crowd.

ICYMI: Investigative reporting is ‘still a very white male business’

During the panel, Kang acknowledged having an epiphany about his own privilege, including a father who immigrated to the United States for a post-doctoral position at Harvard. “I’m still really pissed off that David Remnick did not make me a staff writer at The New Yorker. And I thought about it and realized, I think I’m mad about that, and that’s why I’ve been so mad about media diversity. That’s fucked up. It’s so privileged. I think that’s where the representation stuff comes in. I don’t know anyone in media who doesn’t come from rich parents. The media is so overwhelmingly upper-middle class. Writing about race now has become the racial anxieties of that class of people, and I just find it insanely boring.”

Still, he admitted to the audience that his Korean-American identity does sometime help him in his work, such as being able to speak in Korean “like a 5-year-old” to the victims of the Oikos school shooting or during the impeachment protests in South Korea. “I was able to get into spaces that some of the white reporters were not able to get into,” he says. “But there’s so few spots where you can use that advantage.”

***

Kang is in a weird position, for all of his accomplishments. “Am I the most successful Asian magazine writer who writes about Asian people from a personal perspective?” he says. “That’s great. I’m also the only one.”

He’s also in an uncharted position in his personal life. In January, two months after Donald Trump was elected, Kang’s daughter was born. Kang admits he briefly considered moving his family to New Zealand, where his sister lives, if the situation for minorities like him and his daughter became much worse in the US. But that feeling passed within a month or so. “It was overcome with the reality that even if you’re in New York or California, these things still happen,” he says. “It’s not like life as a minority was really easy before Trump, and now it’s really hard. [Racism is] just more out there.”

With a baby in the picture, Kang’s ideas about the future of his career are now mostly tethered to ensuring his family has enough money to raise his little girl rather than how he’ll stay in media. “At a time when our industry is imploding and everyone is losing their job, you’re very aware the end may come and you might have to do something with your life where all the connections you’ve built are somewhat irrelevant,” he says.

“I can’t be as cavalier as I was five years ago.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.